Cardionerds: A Cardiology Podcast

CardioNerds

Cardionerds is a medical cardiology podcast and platform that democratizes cardiovascular education and brings high yield cardiovascular concepts in a fun and engaging format to listeners of all levels.

- 18 minutes 42 seconds408. Journal Club: The SUMMIT Trial with Dr. Milton Packer

Join CardioNerds Heart Failure Section Chair Dr. Jenna Skowronski, episode lead Dr. Merna Hussein, and expert faculty Dr. Milton Packer as they discuss the SUMMIT trial.

The SUMMIT trial randomized 731 patients with HFpEF with LVEF ≥ 50% and obesity with BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 to receive tirzepatide or placebo for at least 52 weeks. The two co-primary endpoints were a composite of time to cardiovascular death or a worsening heart failure event and quality of life measured by the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire clinical summary score (KCCQ-CSS). Treatment with tirzepatide led to a lower risk of the composite of cardiovascular death or worsening heart failure as well as improved quality of life.

This episode was planned in collaboration with the American College of Cardiology Section of the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with mentorship from Section Chair Dr. Eugenia Gianos.

US Cardiology Review is now the official journal of CardioNerds! Submit your manuscript here.

CardioNerds Journal Club Page

CardioNerds Episode Page

CardioNerds Academy

Cardionerds Healy Honor RollCardioNerds Journal Club

Subscribe to The Heartbeat Newsletter!

Check out CardioNerds SWAG!

Become a CardioNerds Patron!References – The SUMMIT Trial

Packer, M., Zile, M. R., Kramer, C. M., Baum, S. J., Litwin, S. E., Menon, V., Ge, J., Weerakkody, G. J., Ou, Y., Bunck, M. C., Hurt, K. C., Murakami, M., Borlaug, B. A., & SUMMIT Trial Study Group. (2024). Tirzepatide for Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction and Obesity. The New England Journal of Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2410027

21 January 2025, 5:00 am - 19 minutes 23 seconds407. Journal Club: The Nex-Z Trial – A CRISPR-Cas9 Based Treatment for ATTR Cardiac Amyloidosis with Dr. Ronald Witteles

Join CardioNerds Heart Failure Section Chair Dr. Jenna Skowronski, episode lead Dr. Apoorva Gangavelli, and expert faculty Dr. Ronald Witteles as they discuss the Nex-Z trial.

This was a phase 1, open-label trial investigating nex-z, a CRISPR-Cas9-based treatment, in 36 patients with transthyretin amyloidosis with cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM). The primary objectives were aimed at studying the safety and pharmacodynamics of this novel gene-based treatment modality. This episode dives into the nuances of the data, future directions for investigation, and future clinical implications.

US Cardiology Review is now the official journal of CardioNerds! Submit your manuscript here.

CardioNerds Journal Club Page

CardioNerds Episode Page

CardioNerds Academy

Cardionerds Healy Honor RollCardioNerds Journal Club

Subscribe to The Heartbeat Newsletter!

Check out CardioNerds SWAG!

Become a CardioNerds Patron!References – The Nex-Z Trial

Fontana, M., Solomon, S. D., Kachadourian, J., Walsh, L., Rocha, R., Lebwohl, D., Smith, D., Täubel, J., Gane, E. J., Pilebro, B., Adams, D., Razvi, Y., Olbertz, J., Haagensen, A., Zhu, P., Xu, Y., Leung, A., Sonderfan, A., Gutstein, D. E., & Gillmore, J. D. (2024). CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing with Nexiguran Ziclumeran for ATTR Cardiomyopathy. The New England Journal of Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2412309

16 January 2025, 9:08 pm - 26 minutes 41 seconds406. Journal Club: The BPROAD Trial with Dr. Keith Ferdinand

Join CardioNerds co-founder Dr. Daniel Ambinder, episode lead Dr. Nidhi Patel, and expert faculty Dr. Keith Ferdinand as they discuss the BP ROAD trial.

The BP ROAD trial randomized 12,821 patients 50 years of age or older with type 2 diabetes, elevated systolic blood pressure, and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease to receive intensive treatment that targeted a systolic blood pressure of less than 120 mm Hg or standard treatment that targeted a systolic blood pressure of less than 140 mm Hg for up to 5 years. Investigators found a significant reduction of major cardiovascular events with intensive blood pressure lowering. This episode dives into the nuances of the data and clinical implications.

This episode was planned in collaboration with the American College of Cardiology Section of the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with mentorship from Section Chair Dr. Eugenia Gianos.

US Cardiology Review is now the official journal of CardioNerds! Submit your manuscript here.

CardioNerds Journal Club Page

CardioNerds Episode Page

CardioNerds Academy

Cardionerds Healy Honor RollCardioNerds Journal Club

Subscribe to The Heartbeat Newsletter!

Check out CardioNerds SWAG!

Become a CardioNerds Patron!References – BPROAD Trial

Bi, Y., Li, M., Liu, Y., Li, T., Lu, J., Duan, P., Xu, F., Dong, Q., Wang, A., Wang, T., Zheng, R., Chen, Y., Xu, M., Wang, X., Zhang, X., Niu, Y., Kang, Z., Lu, C., Wang, J., … Wang, W. (2024). Intensive Blood-Pressure Control in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2412006

15 January 2025, 12:41 am - 31 minutes 47 seconds405. Case Report: Like Mother, Like Son? Peripartum Cardiomyopathy and Infantile Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Lead to a Unifying Diagnosis – Mayo Clinic Arizona

CardioNerds (Dr. Dan Ambinder and guest host, Dr. Pooja Prasad) join Dr. Donny Mattia from Phoenix Children’s pediatric cardiology fellowship, Dr. Sri Nayak from the Mayo Clinic – Arizona adult cardiology fellowship, and Dr. Harrison VanDolah from the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix Med/Peds program for a sunrise hike of Piestewa Peak, followed by some coffee at Berdena’s in Old Town Scottsdale (before the bachelorette parties arrive), then finally a stroll through the Phoenix Desert Botanical Gardens to discuss a thought-provoking case series full of clinical cardiology pearls. Expert commentary is provided by Dr. Tabitha Moe. Episode audio was edited by Dan Ambinder.

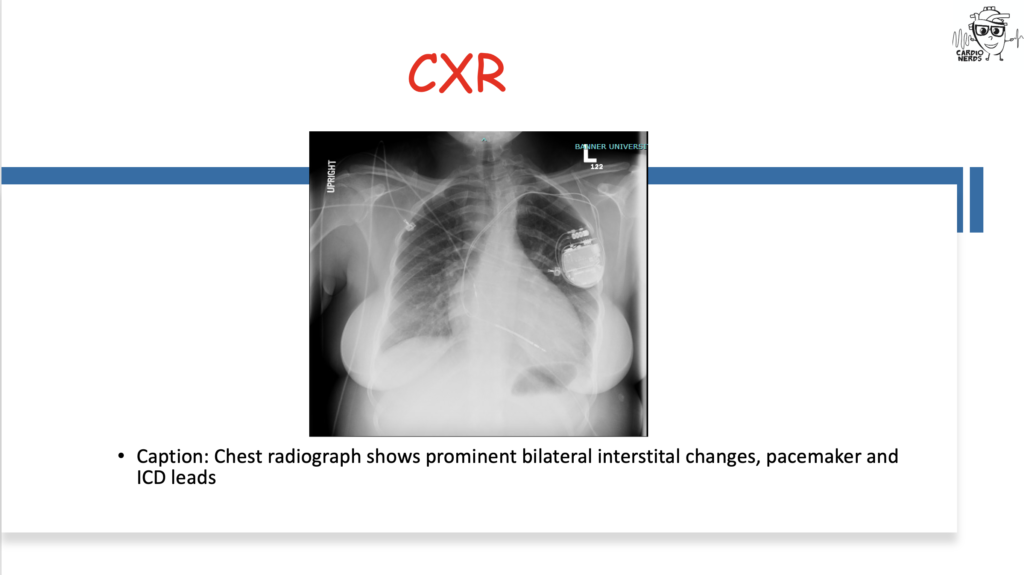

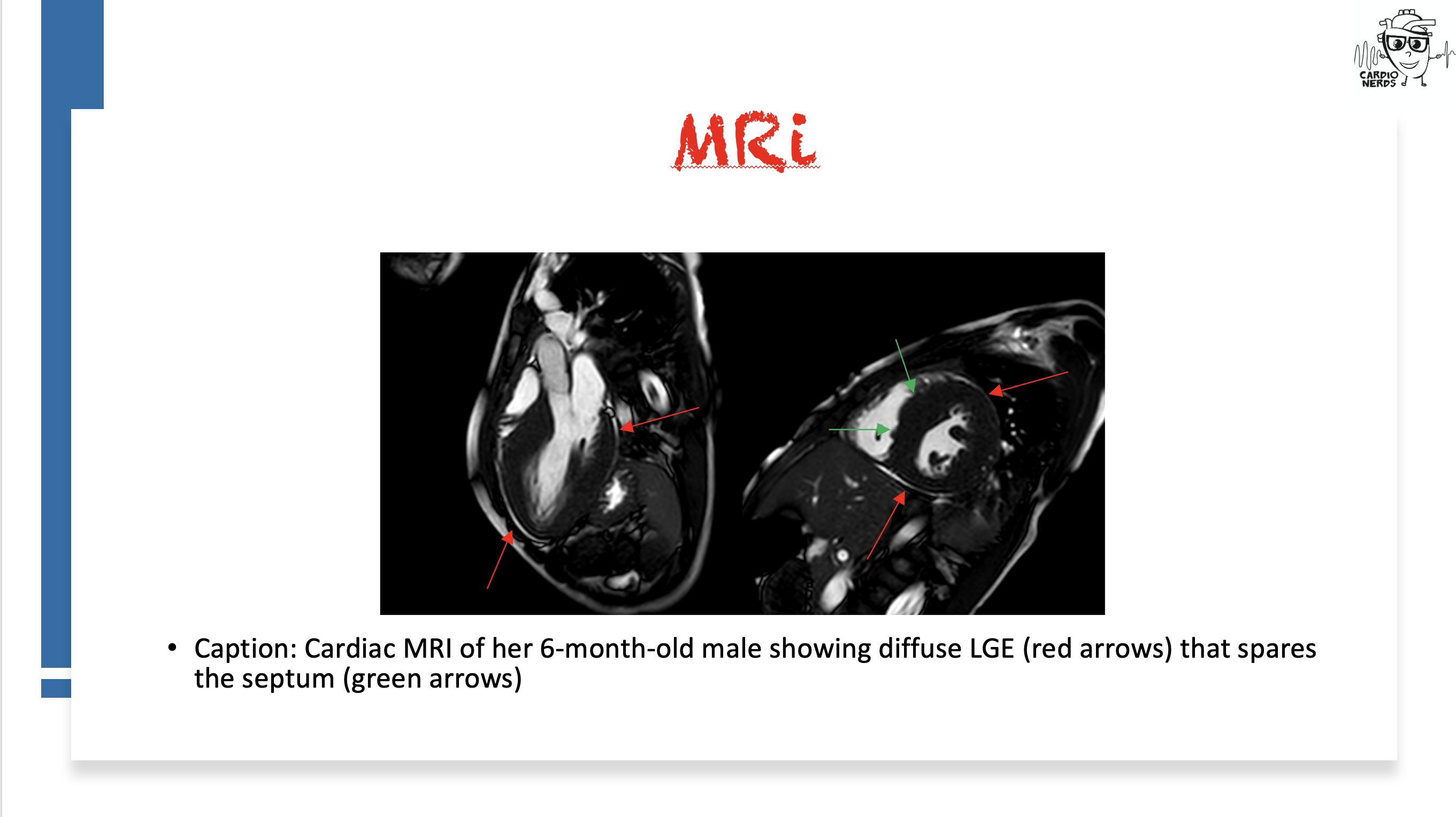

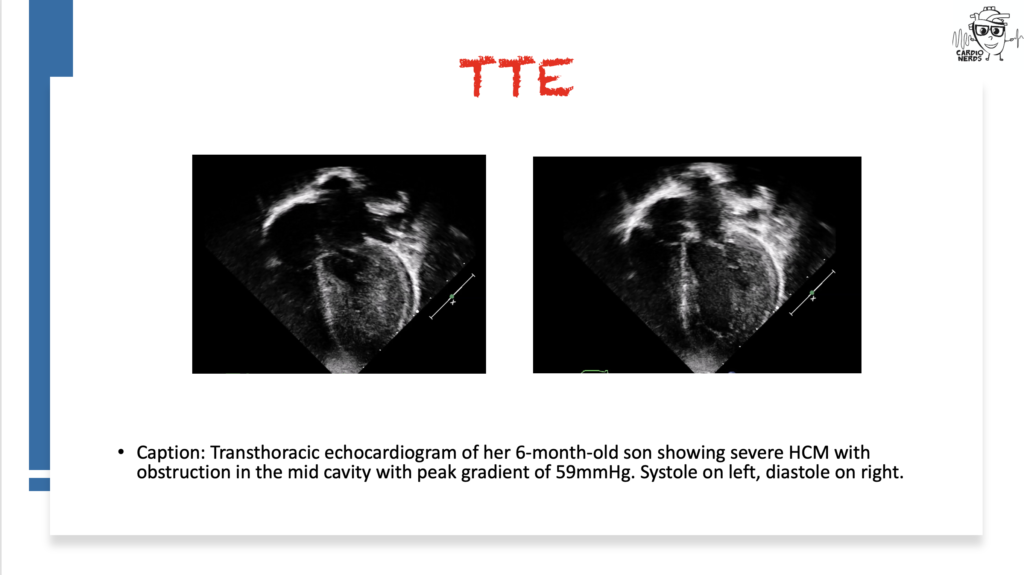

They discuss the following case: Cardiology is consulted by the OB team for a 27-year-old female G1, now P1, who has just delivered a healthy baby boy at 34 weeks gestation after going into premature labor. She is experiencing shortness of breath and is found to have a significant past cardiac history, including atrial fibrillation and preexcitation, now with a pacemaker and intracardiac defibrillator. We review the differential diagnosis for peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM) and then combine findings from her infant son, who is seen by our pediatric cardiology colleagues and is found to have severe hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). Genetic testing for both ultimately reveals a LAMP2 mutation consistent with Danon Disease. The case discussion focuses on the differential diagnosis for PPCM, HCM, pearls on Danon Disease and other HCM “phenocopies,” and the importance of good history.

“To study the phenomena of disease without books is to sail an uncharted sea, while to study books without patients is not to go to sea at all.” – Sir William Osler. CardioNerds thank the patients and their loved ones whose stories teach us the Art of Medicine and support our Mission to Democratize Cardiovascular Medicine.

US Cardiology Review is now the official journal of CardioNerds! Submit your manuscript here.

CardioNerds Case Reports Page

CardioNerds Episode Page

CardioNerds Academy

Cardionerds Healy Honor RollCardioNerds Journal Club

Subscribe to The Heartbeat Newsletter!

Check out CardioNerds SWAG!

Become a CardioNerds Patron!Case Media

Pearls

- Peripartum cardiomyopathy is a diagnosis of exclusion – we must exclude other possible etiologies of heart failure!

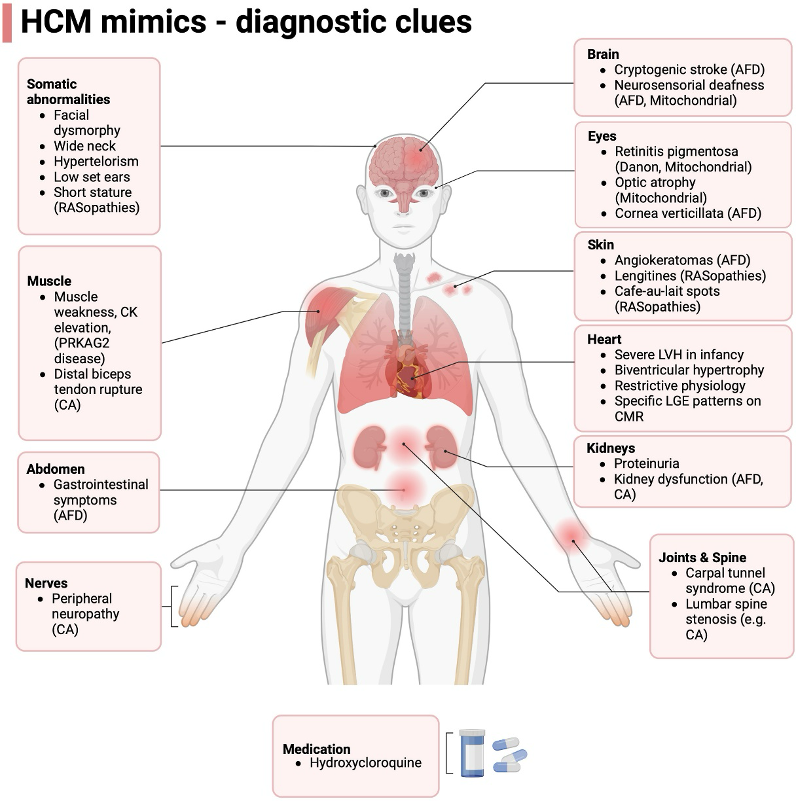

- Be on the lookout for features of non-sarcomeric HCM – as Dr. Michelle Kittleson said in Episode 166, “LVH plus” states. HCM with preexcitation, heart block, strong family history, or extracardiac symptoms such as peripheral neuropathy, myopathy, or cognitive impairment should be evaluated for infiltrative/inherited cardiomyopathies!

- As an X-linked dominant disorder, Danon disease will present differently in males vs females, with males having much more severe and earlier onset disease with extracardiac features.

- Making the diagnosis for genetic disorders such as Danon disease is important for getting the rest of family members tested as well as the opportunity for specialized treatments such as gene therapy

- Up to 5% of Danon disease cases may be due to copy number variants, which may be missed in genetic testing that does not do targeted deletion/duplication analysis!).

Notes

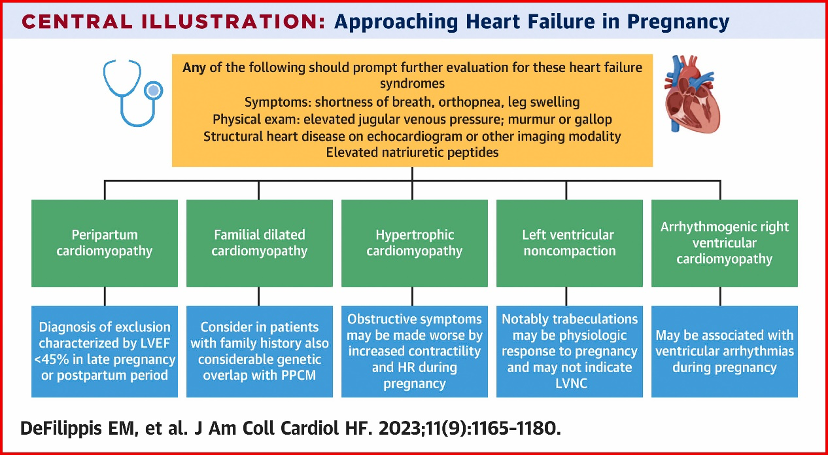

What is the differential diagnosis for peripartum cardiomyopathy?

- Peripartum cardiomyopathy is a diagnosis of exclusion – we must exclude other possible etiologies of heart failure!

- First, ensure that you are not missing an acute life-threatening etiology of acute decompensated heart failure – pulmonary embolism, amniotic fluid embolism, ACS, and SCAD should all be ruled out.

- Second, a careful history can identify underlying heart disease or risk factors for the development of heart failure, such as substance use, high-risk behaviors that put one at risk for HIV infection, and family history that suggests an inheritable cardiomyopathy.

- Lastly, a careful review of echocardiographic imaging may also identify underlying etiologies that warrant a change in management.

- Diagnosis of peripartum cardiomyopathy is important to consider as within 7 days of onset, patients may be eligible for treatment with bromocriptine – consider referring the patient for enrollment in the ongoing RCT ReBIRTH.

- Check out Cardionerds Episode 113 and the great article linked below for more details on heart failure in pregnancy and postpartum!

What is the differential diagnosis for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy?

- Though by far the most common differential diagnosis for HCM is simple LVH or athlete’s heart, as Dr. Michelle Kittleson taught us in CardioNerds Episode 166, we should “remain alert for “LVH+” states.”

- It is helpful to think of them in two buckets – sarcomeric mutations (classic HCM) or non-sarcomeric causes (“phenocopies”).

- If you see systemic signs like peripheral neuropathy, renal dysfunction, or skin changes – clues towards a systemic pathology (for adult colleagues, first think amyloidosis; for peds, colleagues, think genetic syndromes such as RASopathies like Noonan syndrome, glycogen, and lysosomal storage diseases like Fabry).

- Additionally, certain additional cardiac findings can point towards a non-sarcomeric HCM – recall way back in CardioNerds Episode 68 when our friends at VCU presented a man in his 60s with a history of WPW/preexcitation and HCM and was found to have a PRKAG2 mutation, which is a similar lysosomal vacuolopathy to Danon disease. Another example was seen in Episode 349 when we saw a patient with HCM and heart block who was found to have Fabry disease.

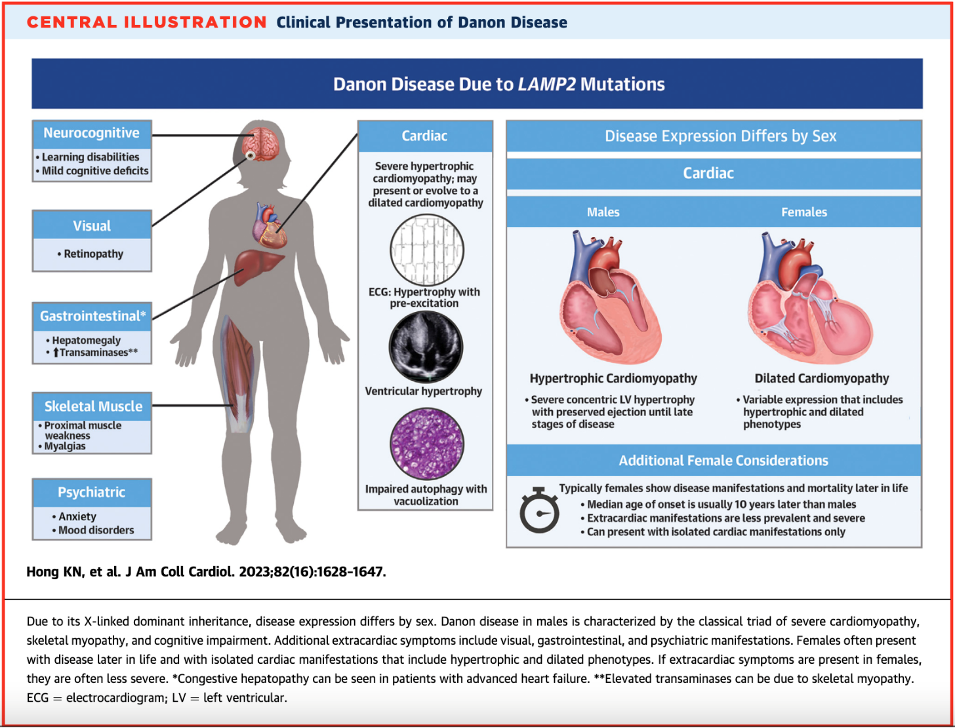

What is Danon disease, and how does it present?

- Danon disease is a rare X-linked dominant genetic disorder due to deficiency in LAMP2, a glycoprotein involved in protecting the lysosome from its roles in endocytosis and autophagy

- When deficiency of LAMP2 occurs, products build up into vacuoles and lead to cardiomyocyte dysfunction and death.

- Interestingly, autophagy disruption is the suspected mechanism of cardiomyopathies from anthracyclines and hydroxychloroquine – Danon disease severity underscores the importance of this process!

- Estimated prevalence of Danon disease in adult patients with HCM is 1-4%, however when both HCM and pre-excitation are present, this rises to 17%.

- It is highly penetrant, meaning most patients with the mutation will show symptoms.

- There are several extracardiac features such as skeletal myopathy, retinopathy, and cognitive impairment – these correlated with areas in the body where LAMP2 is expressed more!

- Classic presentations – remember that X-linked inheritance results in differential expression between males and females!

- Males: young onset with severe LVH/HCM and extracardiac phenotype

- Females: isolated cardiomyopathy (can be either dilated or hypertrophic) with preexcitation arrhythmias with a family history suggesting X-linked dominant transmission (i.e., males more severely affected than females).

- When taking a family history, note that male-to-male transmission (can’t happen since males don’t pass on an X chromosome to their male children) or female-to-offspring transmission (suggests mitochondrial disease) should prompt alternate diagnosis. However, an estimated 1/3 of Danon disease cases are de novo mutations!

- See Episode 300 for a great in-depth overview of the pathophysiology of Danon disease

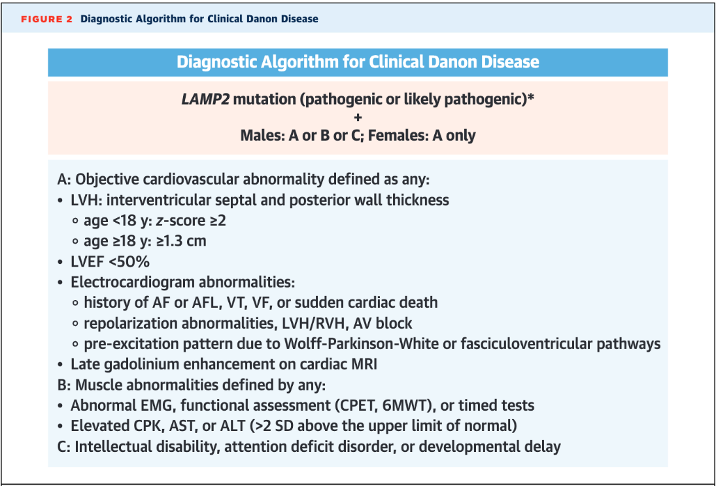

How is Danon disease diagnosed?

- Though there are some proposed characteristic cardiac MRI findings (diffuse LGE sparing the interventricular septum), diagnosis is genetic with a loss-of-function mutation in LAMP2 paired with characteristic cardiac or extracardiac features (see below diagnostic algorithm from Hong et al. JACC 2023)

- LAMP2 is now included in most hypertrophic and dilated CM panels – if found, it is crucial to ensure the patient’s family members also undergo testing and potentially cardiac evaluation! (Note: up to 5% of Danon disease cases may be due to copy number variants, which may be missed in genetic testing that does not do targeted deletion/duplication analysis!)

- Differential Diagnosis

- Sarcomeric HCM – the “classic” HCM, which has numerous genetic causes, all of which affect the sarcomere with age-related penetrance leading to three peaks in age at onset (infancy <1yr, teenage/early adulthood, and mid-adulthood). Progression towards massive LVH and systolic dysfunction is uncommon (<10%) and should raise suspicion of a rare genocopy such as Danon. EKG is usually mostly normal in these patients, unlike in Danon disease, which often has striking abnormalities.

- Pompe disease – lysosome storage disease from mutations in acid alpha-glucosidase leading to lysosomal glycogen accumulation. Autosomal recessive. It can be an infantile form with severe LVH/HCM, and the later forms can have classic skeletal myopathy as well, but usually, these patients have less severe cardiac features.

- RAS-opathies – genetic diseases due to mutations in the RAS/MAPkinase pathway. Classic examples are Noonan syndrome, LEOPARD syndrome, and Costello syndrome. All have classic extracardiac manifestations as well as oftentimes HCM, as well as congenital heart disease such as pulmonary valve stenosis.

- Fabry disease – also an X-linked recessive lysosomal disorder due to alpha-galactosidase A enzyme deficiency; however, it is rarely prominent in childhood and is usually more characterized by extracardiac manifestations. HCM is a cardiac manifestation presenting in the 30s-40s.

- Friedrich ataxia – autosomal recessive multisystem disease due to GAA sequence expansion in the FXN gene that encodes frataxin, a mitochondrial protein, which impairs mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. “HCM” is a common disease manifestation in addition to the classic severe neurologic presentation.

- Mitochondrial diseases – heterogenous conditions affecting mitochondrial DNA, transmitted in matrilinear pattern, with cardiac hypertrophy being a classic disease manifestation in addition to preexcitation. These may present with severe cognitive impairment than Danon disease.

- PRKAG2 mutations – cause dysregulation of adenosine monophosphate kinase, culminating in accumulation of vacuoles within glycogen stores. Early-onset cardiac hypertrophy with preexcitation can be similar to Danon disease. There are no extracardiac features and the inheritance pattern is autosomal dominant.

- For a great summary, see Table 2 in Hong K et al. International Consensus on Differential Diagnosis and Management of Patients with Danon disease: JACC state-of-the-art Review. JACC 2023 Oct, 82 (16) 1628-1647.

- For patients who undergo heart transplantation for a genetic/inherited cause, it is crucial to recall their index diagnosis after transplant – they may have extracardiac disease manifestations!

References

- Davis M et al. Peripartum cardiomyopathy: JACC state-of-the-art review. JACC 2020 Jan, 75 (2) 207-221. https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.11.014

- DeFilippis EM et al. Cardio-obstetrics and heart failure: JACC: Heart Failure state-of-the-art review. JACC: HF 2023 Sep, 11(9) 1165-1180. https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/j.jchf.2023.07.009_ga=2.84541658.274573079.1723517623-224546423.1716483762

- Hong K et al. International consensus on differential diagnosis and management of patients with Danon disease: JACC state-of-the-art review. JACC 2023 Oct, 82 (16) 1628- 1647. https://www.jacc.org/doi/abs/10.1016/j.jacc.2023.08.014

- Miliou A et al. Danon cardiomyopathy: specific imaging signs. JACC: Case Rep 2022 Nov 6;4(22):1496-1500. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666084922006015

- Padkins MR, Bell MR. 33-year-old woman with postpartum acute shortness of breath. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2020;95(9):2000-2004 https://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org/article/S0025-6196(20)30713-8/fulltext

- Rigolli M et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in Danon disease cardiomyopathy. JACC: Imaging 2021 Feb, 14 (2) 514-516. https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/j.jcmg.2020.08.011

13 December 2024, 2:25 am - 51 minutes 52 seconds404. Case Report: A Stressful Case of Cardiogenic Shock – Tufts Medical Center

CardioNerds (Dr. Dan Ambinder and Dr. Yoav Karpenshif – Chair of the CardioNerds Critical Care Cardiology Council) join Dr. Munim Khan, Dr. Shravani Gangidi, and Dr. Rachel Goodman from Tufts Medical Center’s general cardiology fellowship program for hot pot in China Town in Boston. They discuss a case involving a patient who presented with stress cardiomyopathy leading to cardiogenic shock. Expert commentary is provided by Dr. Michael Faulx from the Cleveland Clinic. Notes were drafted by Dr. Rachel Goodman. Audio editing by Dr. Diane Masket.

A young woman presents with de novo heart-failure cardiogenic shock requiring temporary mechanical circulatory support who is found to have basal variant takotsubo cardiomyopathy. We review the definition and natural history of takotsubo cardiomyopathy, discuss initial evaluation and echocardiographic findings, and review theories regarding pathophysiology of the clinical syndrome. We also highlight complications of takotsubo cardiomyopathy, with a focus on left ventricular outflow obstruction, cardiogenic shock, and arrythmias.

“To study the phenomena of disease without books is to sail an uncharted sea, while to study books without patients is not to go to sea at all.” – Sir William Osler. CardioNerds thank the patients and their loved ones whose stories teach us the Art of Medicine and support our Mission to Democratize Cardiovascular Medicine.

US Cardiology Review is now the official journal of CardioNerds! Submit your manuscript here.

CardioNerds Case Reports Page

CardioNerds Episode Page

CardioNerds Academy

Cardionerds Healy Honor RollCardioNerds Journal Club

Subscribe to The Heartbeat Newsletter!

Check out CardioNerds SWAG!

Become a CardioNerds Patron!Pearls

- Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is defined as a reversible systolic dysfunction with wall motion abnormalities that do not follow a coronary vascular distribution.

- Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is a diagnosis of exclusion; patients often undergo coronary angiography to rule out epicardial coronary artery disease given an overlap in presentation and symptoms with acute myocardial infarction.

- There are multiple echocardiographic variants of takotsubo. Apical ballooning is the classic finding, but mid-ventricular, basal, and biventricular variants exist as well.

- Patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy generally recover, but there are important complications to be aware of. These include arrhythmia, left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction related to a hyperdynamic base in the context of apical ballooning, and cardiogenic shock.

- Patients with Impella devices are at risk of clot formation and stroke. Assessing the motor current can be a clue to what is happening at the level of the motor or screw.

Notes

What is Takotsubo Syndrome (TTS)?

- TTS is a syndrome characterized by acute heart failure without epicardial CAD with regional wall motion abnormalities seen on echocardiography that do not correspond to a coronary artery territory (see below).1

- TTS classically develops following an acute stressor—this can be an emotional or physical stressor.1

- An important feature of TTS is that the systolic dysfunction is reversible. The time frame of reversibility is variable, though generally hours to weeks.2

- Epidemiologically, TTS has a predilection for post-menopausal women, however anyone can develop this syndrome.1

- TTS is a diagnosis of exclusion. Coronary artery disease (acute coronary syndrome, spontaneous coronary artery dissection, coronary embolus, etc) should be excluded when considering TTS. Myocarditis is on the differential diagnosis.

What are the echocardiographic findings of takotsubo cardiomyopathy?

- The classic echocardiographic findings of TTS is “apical ballooning,” which is a way of descripting basal hyperkinesis with mid- and apical hypokinesis, akinesis, or dyskinesis.3

- There are multiple variants of TTS. The four most common are listed below:3

- (1) Apical ballooning (classic TTS)

- (2) Mid-ventricular variant

- (3) Basal variant

- (4) Focal variant

- Less common variants include the biventricular variant and the isolated right ventricular variant.3

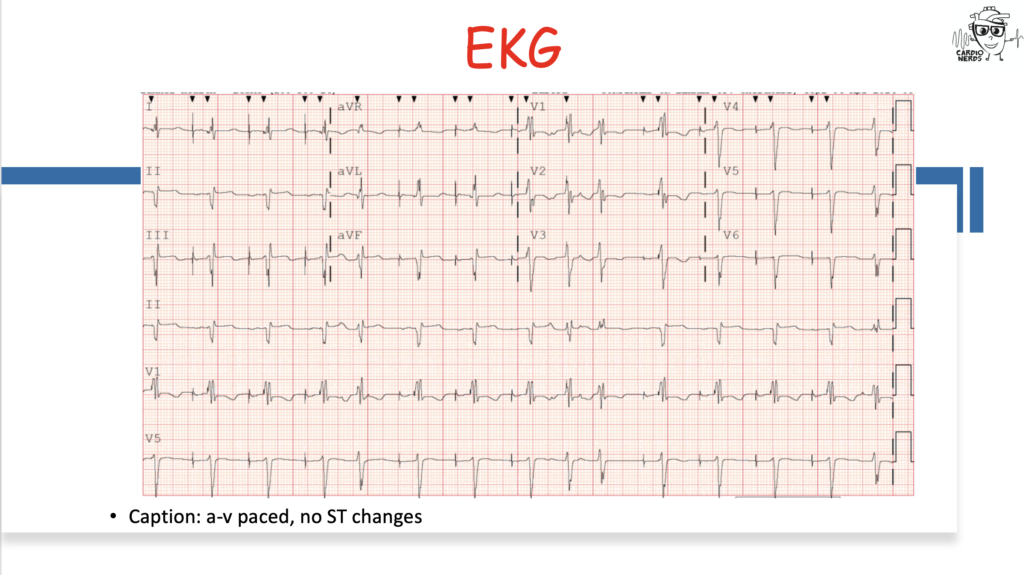

Do patients with TTS generally have EKG changes or biomarker elevation?

- Patients often have elevated troponin, though the severity wall motion abnormalities seen on TTE is generally out of proportion to the degree of troponin elevation.4

- BNP/NTproBNP are typically elevated, especially early in the course.4

- During the acute phase (defined as within the first 12 hours), patients may have ST elevation or depression, T wave inversions, new LBBB, or QT prolongation.4

What are complications of takotsubo cardiomyopathy?

- Heart failure2

- LV outflow tract obstruction—if there is an LVOT obstruction, it is important to avoid diuretics, vasodilators such as nitroglycerin, and inotropic agents.2

- Cardiogenic shock.2

- Atrial and ventricular arrhythmias.2

- LV thrombus—this is of particular risk in patients with the classic “apical ballooning” variant of takotsubo due to apical akinesis and therefore stagnant flow.2

References

- Lyon AR, Citro R, Schneider B, et al. Pathophysiology of Takotsubo Syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(7):902-921. doi:10. 1016/j.jacc.2020.10.060

- Singh T, Khan H, Gamble DT, Scally C, Newby DE, Dawson D. Takotsubo Syndrome: Pathophysiology, Emerging Concepts, and Clinical Implications. Circulation. 2022;145(13):1002-1019. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.055854

- Ghadri JR, Wittstein IS, Prasad A, et al. International Expert Consensus Document on Takotsubo Syndrome (Part I): Clinical Characteristics, Diagnostic Criteria, and Pathophysiology. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(22):2032-2046. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehy076

- Current state of knowledge on Takotsubo syndrome: a Position Statement from the Taskforce on Takotsubo Syndrome of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology – Lyon – 2016 – European Journal of Heart Failure – Wiley Online Library

18 November 2024, 4:20 am - 36 minutes 39 seconds403. Cardio-Rheumatology: Treating Inflammation and Real-World Implementation of Therapies with Dr. Brittany Weber and Dr. Michael Garshick

In this episode, CardioNerds Dr. Gurleen Kaur and Dr. Akiva Rosenzveig are joined by Cardio-Rheumatology experts, Dr. Brittany Weber and Dr. Michael Garshick to discuss treating inflammation, delving into the pathophysiology behind the inflammatory hypothesis of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and the evolving data on anti-inflammatory therapies for reducing ASCVD risk, with insights on real-world implementation.

Show notes were drafted by. Dr. Akiva Rosenzveig.

This episode was produced in collaboration with the American Society of Preventive Cardiology (ASPC) with independent medical education grant support from Agepha Pharma.

American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions 2024

- As heard in this episode, the American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions 2024 is coming up November 16-18 in Chicago, Illinois at McCormick Place Convention Center. Come a day early for Pre-Sessions Symposia, Early Career content, QCOR programming and the International Symposium on November 15. It’s a special year you won’t want to miss for the premier event for advancements in cardiovascular science and medicine as AHA celebrates its 100th birthday. Registration is now open, secure your spot here!

- When registering, use code NERDS and if you’re among the first 20 to sign up, you’ll receive a free 1-year AHA Professional Membership!

US Cardiology Review is now the official journal of CardioNerds! Submit your manuscript here.

CardioNerds Prevention Page

CardioNerds Episode Page

CardioNerds Academy

Cardionerds Healy Honor RollCardioNerds Journal Club

Subscribe to The Heartbeat Newsletter!

Check out CardioNerds SWAG!

Become a CardioNerds Patron!Pearls – Treating Inflammation

- Our understanding of the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis has undergone a few iterations from the incrustation hypothesis to the lipid hypothesis to the response-to-injury hypothesis and culminating with our current understanding of the inflammation hypothesis.

- Both the adaptive and innate immune systems play instrumental roles in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis.

- After adequately controlling classic modifiable risk factors such as blood pressure, dyslipidemia, glucose intolerance, and obesity, systemic inflammation as assessed by CRP can be ascertained as CRP is associated with ~1.8-fold increased risk of cardiovascular events

- Although the most common side effect of colchicine is gastrointestinal intolerance, colchicine can induce lactose intolerance, so a lactose free diet may help ameliorate colchicine-induced GI symptoms.

- Anti-inflammatory therapeutics have shown promise in reducing cardiovascular risk but much more is to be learned with ongoing and future basic, translational, and clinical research.

Show notes – Treating Inflammation

- What are the origins of the inflammatory hypothesis?

- The first hypothesis as to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis was the incrustation hypothesis by Carl Von Rokitansky in 1852. He suggested that atherosclerosis begins in the intima with thrombus deposition.In 1856, Rudolf Virchow suggested the lipid hypothesis whereby high levels of cholesterol in the blood lead to atherosclerosis. He observed inflammatory changes in the arterial walls associated with atherosclerotic plaque growth, called endo-arteritis chronica deformans.In 1977, Russell Ross suggested the response-to-injury hypothesis, that atherosclerosis develops from injury to the arterial wall.In the 1990’s the role of inflammation in ASCVD became more recognized. Both the adaptive and innate immune system are critical in atherosclerosis. Lipids and inflammation are synergistic in that lipid exposure is required but they translocate through damaged endothelium which occurs by way of inflammatory cytokines, namely within the NLRP3 inflammasome (IL-1, IL-6 etc.).Smooth muscle cells are also involved. They migrate to the endothelial region and secrete collagen to create the fibrous cap. They can also transform into macrophage-like cells to take up lipids and become foam cells.

- T, B, and K cells are also part of this milieu. In fact, neutrophils, macrophages and monocytes make up only a small portion of the cells involved in the atherosclerotic process.

- What are ways to individually optimize one’s ASCVD risk?

- Ensure the patient is on appropriate antiplatelet therapy, lipid lowering therapy, blood pressure is well controlled, and the Hemoglobin A1c is well controlled. Smoking cessation is pivotal.

- If the patient has an elevated Lipoprotein (a), pursue more aggressive lipid lowering therapy. Targeted therapies may become available in the future.

- Assess the patient’s systemic inflammatory risk as measured by C-Reactive Protein (CRP)

- What is the evidence for utilizing CRP in risk stratification?

- CRP, initially termed Fraction C (discovered as a c polysaccharide component of the pneumococcal cell wall), was first discovered at Rockefeller University in the 1930’s. It was discovered to be an acute phase reactant in the 1940’s and noted to be synthesized in the liver in the 1960’s.

- Although it is not causal in atherosclerosis, elevated CRP is associated with elevated rates of cardiovascular disease. This was first noted in the landmark New England Journal of Medicine study by Ridker et al that showed elevated CRP was associated with elevated cardiovascular risk and treating with anti-inflammatory medication (aspirin) lowered CRP and CV risk.

- The statin trials also showed reduction in CRP levels was associated with better outcomes.

- High-sensitivity CRP (hsCRP) >3 mg/L has odds ratio of ~1.8 for risk of CV disease.

- Recent analyses of the PROMINENT, REDUCE-IT, and STRENGTH trials demonstrated that hsCRP was a more powerful determinant of recurrent CV events, CV death, and all-cause mortality than LDL-C.

- After effectively controlling the previously stated modifiable risk factors, what therapeutic options remain in a patient with an elevated CRP?

- CANTOS trial was the first proof of concept trial investigating Canakinumab (an IL-1 inhibitor) which showed a ~15% relative risk reduction in cardiovascular events

- CIRT trial investigated methotrexate in patients without autoimmune disease. It was stopped early due to it being a negative trial. This emphasized the complex role inflammation plays in ASCVD, and that both patient selection and chosen anti-inflammatory therapy are important to consider for ASCVD risk reduction.

- Colchicine has seen a lot of focus in this space with trials such as COLCOT, COPS, LODOCO, LODOCO 2, LODOCO MI. Overall, it appears that colchicine may be more effective in chronic stable ischemic heart disease. The CLEAR SYNERGY trial investigated colchicine in the peri-MI period and was a negative trial. However, we do not yet have the published data to further analyze it.

- A review article by Potere et al (referenced below) provides a useful summary of novel therapies and upcoming trials in the inflammation in ASCVD space.

- How do we approach inflammation in women?

- We know that immune response differs between men and women. Women have more robust immune response to vaccines and viruses and greater innate and adaptive immune responses.

- Women have slightly higher CRP than men. Studies have shown that average high sensitivity hsCRP is 1.7 for women and 1.2 for men. In the JUPITER trial, the subgroup of patients with hsCRP>7 mg/L had the highest proportion of women relative to men.

- Regardless, hsCRP remains a reliable predictor of CV events in both men and women.

- What are some practical considerations when starting colchicine?

- It may help with adherence, if you walk patients through what to expect with the medication.

- Obtain renal and liver function tests as both organs contribute to colchicine metabolism and clearance.

- Obtain a thorough medication reconciliation as colchicine has some notable drug-drug interactions.

- The most common side effects is GI intolerance; cytopenias are rare occurrences.

- Note that colchicine can induce lactose intolerance, a potential mechanism for causing GI intolerance, so a lactose free diet may help with adherence.

- What do we have to look forward to in the anti-inflammation space in CV disease?

References – Treating Inflammation

14 November 2024, 3:57 am - 8 minutes402. Guidelines: 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure – Question #39 with Dr. Robert Mentz

The following question refers to Sections 7.3.3 and 7.3.6 of the 2022 ACC/AHA/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure.

The question is asked by Palisades Medical Center medicine resident & CardioNerds Academy Fellow Dr. Maryam Barkhordarian, answered first by UTSW AHFT Cardiologist & CardioNerds FIT Ambassador Dr. Natalie Tapaskar, and then by expert faculty Dr. Robert Mentz.

Dr. Mentz is associate professor of medicine and section chief for Heart Failure at Duke University, a clinical researcher at the Duke Clinical Research Institute, and editor-in-chief of the Journal of Cardiac Failure. Dr. Mentz has been a mentor for the CardioNerds Clinical Trials Network as lead principal investigator for PARAGLIDE-HF and is a series mentor for this very Decipher the Guidelines Series. For these reasons and many more, he was awarded the Master CardioNerd Award during ACC22.

The Decipher the Guidelines: 2022 AHA / ACC / HFSA Guideline for The Management of Heart Failure series was developed by the CardioNerds and created in collaboration with the American Heart Association and the Heart Failure Society of America. It was created by 30 trainees spanning college through advanced fellowship under the leadership of CardioNerds Cofounders Dr. Amit Goyal and Dr. Dan Ambinder, with mentorship from Dr. Anu Lala, Dr. Robert Mentz, and Dr. Nancy Sweitzer. We thank Dr. Judy Bezanson and Dr. Elliott Antman for tremendous guidance.

American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions 2024

- As heard in this episode, the American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions 2024 is coming up November 16-18 in Chicago, Illinois at McCormick Place Convention Center. Come a day early for Pre-Sessions Symposia, Early Career content, QCOR programming and the International Symposium on November 15. It’s a special year you won’t want to miss for the premier event for advancements in cardiovascular science and medicine as AHA celebrates its 100th birthday. Registration is now open, secure your spot here!

- When registering, use code NERDS and if you’re among the first 20 to sign up, you’ll receive a free 1-year AHA Professional Membership!

Ms. Kay Lotsa is a 48-year-old woman with a history of CKD stage 2 (baseline creatinine ~1.2 mg/dL) & type 2 diabetes mellitus. She has recently noticed progressively reduced exercise tolerance, leg swelling, and trouble lying flat. This prompted a hospital admission with a new diagnosis of decompensated heart failure. A transthoracic echocardiogram reveals LVEF of 35%. Ms. Lotsa is diuresed to euvolemia, and she is started on carvedilol 25mg BID, sacubitril/valsartan 49-51mg BID, and empagliflozin 10mg daily, which she tolerates well. Her eGFR is at her baseline of 55 mL/min/1.73 m2 and serum potassium concentration is 3.9 mEq/L. Your team is anticipating she will be discharged home in the next one to two days and wants to start spironolactone. Which of the following is most important regarding her treatment with mineralocorticoid antagonists?

A

Spironolactone is contraindicated based on her level of renal impairment and should not be started

B

Serum potassium levels and kidney function should be assessed within 1-2 weeks of starting spironolactone

C

Eplerenone confers a higher risk of gynecomastia than does spironolactone

D

The patient will likely not benefit from initiation of spironolactone if her cardiomyopathy is ischemic in origin

Explanation

The correct answer is B – after starting a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA), it is important to closely monitor renal function and serum potassium levels.

MRA (also known as aldosterone antagonists or anti-mineralocorticoids) show consistent improvements in all-cause mortality, HF hospitalizations, and SCD across a wide range of patients with HFrEF.

The RALES trial of spironolactone vs. placebo in highly symptomatic HFrEF (LVEF ≤ 35%, NYHA III-IV), trial of eplerenone vs placebo post-MI in patients with LVEF ≤ 40%, and EMPHASIS-HF trial of eplerenone vs placebo in less symptomatic HFrEF (LVEF ≤ 35%, NYHA II) altogether suggest MRAs confer improvements in all-cause mortality, HF hospitalizations, and sudden cardiac death in patients with HFrEF. Importantly, these benefits have been demonstrated across a wide range of HFrEF severity and etiologies, including ischemic cardiomyopathy (Option D).

Therefore, in patients with HFrEF and NYHA class II to IV symptoms, an MRA (spironolactone or eplerenone) is recommended to reduce morbidity and mortality, if eGFR is >30 mL/min/1.73 m2 and serum potassium is <5.0 mEq/L. Careful monitoring of potassium, renal function, and diuretic dosing should be performed at initiation and closely monitored thereafter to minimize risk of hyperkalemia and renal insufficiency (Class 1, LOE A). MRA therapy in this context provides high economic value.

Adverse Effects of MRAs

Both spironolactone and eplerenone are excreted by the kidney and due to their inhibition of aldosterone signaling, reduce potassium excretion in the urine. For these reasons, the initiation of MRAs is contraindicated in patients with eGFR of ≤30 mL/min/1.73m2 or serum potassium levels of ≥5.0 mEq/L. After starting or intensifying MRA therapy, serum potassium levels and renal function should be rechecked at approximately 1 week, at 4 weeks, and every 6 months thereafter, provided clinical stability. Hyperkalemia can increase the risk of ventricular arrhythmias and death. Unfortunately, this often results in de-escalation or discontinuation of RAASi and a subsequent loss of long-term cardiorenal benefits of maximally tolerated GDMT.

The utility of prescribing potassium binders (e.g., patiromer, sodium zirconium cyclosilicate) to improve outcomes by facilitating continuation of Patiromer and sodium zirconium cyclosilicate remove potassium by exchanging cations leading to increased fecal excretion and thereby lowering serum potassium levels. These have been FDA approved for treatment of hyperkalemia for patients receiving RAASi.

Therefore, the use of potassium binders (patiromer, sodium zirconium cyclosilicate) to improve outcomes by facilitating the continuation of RAASi therapy in patients with HF who experience hyperkalemia (serum potassium level ≥5.5 mEq/L) received a Class 2b recommendation (LOE B-R), but overall utility remains uncertain.

In the DIAMOND trial, patients with HFrEF and hyperkalemia were randomized to patiromer vs. control. In the run-in phase, all patients were started on patiromer, and subsequently, RAASi therapy was initiated/optimized. After this, patients were randomized to continue vs stop patiromer. Hard clinical primary endpoints of time to CV death or first CV hospitalization were changed to mean change in serum potassium due to challenges with recruitment related to the COVID-19 pandemic. There was a significant reduction in the mean change of potassium (0.03 mEq/L in the patiromer group vs. 0.13 mEq/L in the control). Additionally, 85% of the patiromer arm was able to be optimized on RAASi.

Aside from hyperkalemia, troublesome side effects of MRAs include gynecomastia and vaginal bleeding. Eplerenone results in lower rates of these side effects than spironolactone given greater specificity for the aldosterone receptor (Option C).

Main Takeaway

Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, like spironolactone and eplerenone, reduce all-cause mortality, HF hospitalizations, and sudden cardiac death in a wide range of patients with HFrEF. Monitoring renal function and potassium levels while on MRA therapy is imperative.

Guideline Loc.

Section 7.3.3

Section 7.3.6Decipher the Guidelines: 2022 Heart Failure Guidelines Page

CardioNerds Episode Page

CardioNerds Academy

Cardionerds Healy Honor RollCardioNerds Journal Club

Subscribe to The Heartbeat Newsletter!

Check out CardioNerds SWAG!

Become a CardioNerds Patron!13 November 2024, 4:28 am - 12 minutes 33 seconds401. Guidelines: 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure – Question #38 with Dr. Randall Starling

The following question refers to Sections 7.4 and 7.5 of the 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure.

The question is asked by the Director of the CardioNerds Internship Dr. Akiva Rosenzveig, answered first by Vanderbilt AHFT cardiology fellow Dr. Jenna Skowronski, and then by expert faculty Dr. Randall Starling.

Dr. Starling is Professor of Medicine and an advanced heart failure and transplant cardiologist at the Cleveland Clinic where he was formerly the Section Head of Heart Failure, Vice Chairman of Cardiovascular Medicine, and member of the Cleveland Clinic Board of Governors. Dr. Starling is also Past President of the Heart Failure Society of America in 2018-2019. Dr. Staring was among the earliest CardioNerds faculty guests and has since been a valuable source of mentorship and inspiration. Dr. Starling’s sponsorship and support was instrumental in the origins of the CardioNerds Clinical Trials Program.

The Decipher the Guidelines: 2022 AHA / ACC / HFSA Guideline for The Management of Heart Failure series was developed by the CardioNerds and created in collaboration with the American Heart Association and the Heart Failure Society of America. It was created by 30 trainees spanning college through advanced fellowship under the leadership of CardioNerds Cofounders Dr. Amit Goyal and Dr. Dan Ambinder, with mentorship from Dr. Anu Lala, Dr. Robert Mentz, and Dr. Nancy Sweitzer. We thank Dr. Judy Bezanson and Dr. Elliott Antman for tremendous guidance.

American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions 2024

- As heard in this episode, the American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions 2024 is coming up November 16-18 in Chicago, Illinois at McCormick Place Convention Center. Come a day early for Pre-Sessions Symposia, Early Career content, QCOR programming and the International Symposium on November 15. It’s a special year you won’t want to miss for the premier event for advancements in cardiovascular science and medicine as AHA celebrates its 100th birthday. Registration is now open, secure your spot here!

- When registering, use code NERDS and if you’re among the first 20 to sign up, you’ll receive a free 1-year AHA Professional Membership!

Mrs. M is a 65-year-old woman with non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy (LVEF 40%) and moderate to severe mitral regurgitation (MR) presenting for outpatient follow-up. Despite improvement overall, she continues to experience dyspnea on exertion with two flights of stairs and occasional PND. She reports adherence with her medication regimen of sacubitril-valsartan 97-103mg twice daily, metoprolol succinate 200mg daily, spironolactone 25mg daily, empagliflozin 10mg daily, and furosemide 80mg daily. A transthoracic echocardiogram today shows an LVEF of 35%, an LVESD of 60 mm, severe MR with a regurgitant fraction of 60%, and an estimated right ventricular systolic pressure of 40 mmHg. Her EKG shows normal sinus rhythm at 65 bpm and a QRS complex width of 100 ms.

What is the most appropriate recommendation for management of her heart failure?

A

Continue maximally tolerated GDMT; no other changes

B

Refer for cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT)

C

Refer for transcatheter mitral valve intervention

Explanation

Choice C is correct. The 2020 ACC/AHA Guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease outline specific recommendations.

In patients with chronic severe secondary MR related to LV systolic dysfunction (LVEF <50%) who have persistent symptoms (NYHA class II, III, or IV) while on optimal GDMT for HF (Stage D), M-TEER is reasonable in patients with appropriate anatomy as defined on TEE and with LVEF between 20% and 50%, LVESD ≤70 mm, and pulmonary artery systolic pressure ≤70 mmHg (Class 2a, LOE B-R).

Conversely, mitral valve surgery may have a role in the following contexts:

- Severe secondary MR when CABG is planned (Class 2a, LOE B-NR)

- Chronic severe secondary MR related to atrial annular dilation with preserved LV systolic function (LVEF ≥50%) who have severe persistent symptoms (NYHA class III or IV) despite therapy for HF and therapy for associated AF or other comorbidities (Stage D) (Class 2b, LOE B-NR)

- Chronic severe secondary MR related to LV systolic dysfunction (LVEF <50%) who have persistent severe symptoms (NYHA class III or IV) while on optimal GDMT for HF (Stage D) (Class 2b, LOE B-NR).

Choice A is incorrect. GDMT has been shown to improve MR and LV dimensions in patients with HFrEF and secondary MR, and it is a Class 1 recommendation (LOE B-R) to optimize GDMT before any intervention for secondary MR related to LV dysfunction. This includes both medical GDMT and cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) where appropriate. Our patient is still having symptoms despite being on the maximally tolerated doses of medical GDMT. This highlights the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to the management of valvular heart disease in patients with HF in accordance with clinical practice guidelines to prevent worsening of HF and adverse clinical outcomes (Class 1, LOE B-R). A cardiologist with expertise in the management of HF is integral in the shared decision-making for valve intervention and should guide optimization of GDMT to ensure that medical options for HF and secondary MR have been effectively applied for an appropriate time-period and exhausted before considering intervention.

Choice B is incorrect. While CRT has been shown to improve MR, LV dimensions, and outcomes in patients with HFrEF and secondary MR in appropriately selected patients, our patient would not be a candidate given that her QRS duration was < 120ms (Class 3: no benefit, LOE B-R).

Main Takeaway

In patients with severe secondary MR and reduced ejection fraction with persistent symptoms despite GDMT, M-TEER is reasonable in patients with appropriate anatomy as defined on TEE and with LVEF between 20% and 50%, LVESD ≤70 mm, and pulmonary artery systolic pressure ≤70 mmHg. Conversely, surgery may be appropriate for some patients. HF ad VHD should be managed in a multidisciplinary fashion.

Guideline Loc.

Sections 7.4-7.5

Figure 10

Also: Section 7.3 from “Otto, C. M., Nishimura, R. A., Bonow, R. O., Carabello, B. A., rwin, J. P., Gentile, F., Jneid, H., Krieger, ric v., Mack, M., McLeod, C., O’Gara, P. T., Rigolin, V. H., Sundt, T. M., Thompson, A., & Toly, C. (2021). 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. In Circulation (Vol. 143, Issue 5, pp. E72–E227). Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923”

Decipher the Guidelines: 2022 Heart Failure Guidelines Page

CardioNerds Episode Page

CardioNerds Academy

Cardionerds Healy Honor RollCardioNerds Journal Club

Subscribe to The Heartbeat Newsletter!

Check out CardioNerds SWAG!

Become a CardioNerds Patron!11 November 2024, 9:00 pm - 51 minutes 13 seconds400. Cardio-Rheumatology: Targeting Inflammation for Cardiovascular Risk Reduction with Dr. Paul Ridker

In this episode, Dr. Paul Ridker, a pioneer in the field of cardiovascular inflammation, joins the CardioNerds (Dr. Gurleen Kaur, Dr. Richard Ferraro, and Dr. Nidhi Patel) to discuss the evolving landscape of inflammation as a key factor in cardiovascular risk reduction. The discussion dives into the importance of biomarkers like high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) in guiding treatment strategies, the insights gleaned from landmark trials like the JUPITER and CANTOS studies, and the future of targeted anti-inflammatory therapies in cardiology.

Show notes were drafted by Dr. Nidhi Patel. Audio editing by CardioNerds academy intern, Grace Qiu.

This episode was produced in collaboration with the American Society of Preventive Cardiology (ASPC) with independent medical education grant support from Lexicon Pharmaceuticals.

American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions 2024

- As heard in this episode, the American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions 2024 is coming up November 16-18 in Chicago, Illinois at McCormick Place Convention Center. Come a day early for Pre-Sessions Symposia, Early Career content, QCOR programming and the International Symposium on November 15. It’s a special year you won’t want to miss for the premier event for advancements in cardiovascular science and medicine as AHA celebrates its 100th birthday. Registration is now open, secure your spot here!

- When registering, use code NERDS and if you’re among the first 20 to sign up, you’ll receive a free 1-year AHA Professional Membership!

US Cardiology Review is now the official journal of CardioNerds! Submit your manuscript here.

CardioNerds Prevention Page

CardioNerds Episode Page

CardioNerds Academy

Cardionerds Healy Honor RollCardioNerds Journal Club

Subscribe to The Heartbeat Newsletter!

Check out CardioNerds SWAG!

Become a CardioNerds Patron!Pearls – Targeting Inflammation for Cardiovascular Risk

- “If you don’t measure it, you can’t treat it”: Incorporate hs-CRP into routine practice for patients at risk of cardiovascular events, as it provides crucial information for risk stratification and management.

- Recognize the dual benefits of statins in lowering both LDL and inflammation, particularly in patients with elevated hs-CRP.

- Encourage patients to adopt heart-healthy habits, as lifestyle changes remain foundational in reducing both cholesterol and inflammatory risk.

- Reminder that most autoimmune or inflammatory diseases, from psoriasis to Addison’s disease to lupus to scleroderma to inflammatory bowel disease, have been shown to have elevated cardiovascular risk

- Ongoing randomized trials including ZEUS, HERMES, and ARTEMIS will inform whether novel targeting of IL-6 can safely lower cardiovascular event rates or slow renal progression

Show notes – Targeting Inflammation for Cardiovascular Risk

Why is it important to measure both LDL and hs-CRP, and what factors increase hs-CRP?

- Inflammation and hyperlipidemia are synergistic in promoting atherosclerosis. They interact to exacerbate plaque formation and instability, increasing the risk of cardiovascular events.

- Just like we measure blood pressure and LDL to know what to treat, we should measure hs-CRP to guide targeted therapy.

- Clinical Example: in Ms. Flame’s case, despite achieving target LDL levels with statins, her elevated hs-CRP indicates ongoing inflammation and residual cardiovascular risk that should be assessed.

- Residual inflammatory risk should be assessed in both primary and secondary prevention.

- Increased BMI1, smoking2, a sedentary lifestyle3, and genetics4 (such as a higher risk of metabolic disease in South Asians) all raise hs-CRP levels.

- SGLTi5 and GLP-1 agonists6 have also been shown to decrease hs-CRP levels.

What data do we have to support measuring hs-CRP?

- Women’s Health Study7: an early study showing that hs-CRP predicted risk at least as well as LDL cholesterol and that models incorporating hs-CRP in addition to lipids were significantly better at predicting risk than models based on lipids alone.

- JUPITER Trial8 (Primary Prevention): Among patients with normal LDL but elevated hs-CRP there was a 44% reduction in major cardiovascular events (>50% in MI and stroke) and a 20% reduction in all-cause mortality in patients treated with statins. These results led to changes in guidelines in recognizing the need to measure and treat inflammation.

- CANTOS Trial9 (Secondary Prevention): Randomized >10K patients with previous MI and hs-CRP ≥ 2mg/L and found that canakinumab reduced hs-CRP level from baseline in a dose-dependent manner, without reduction in the LDL, ApoB, TG, or blood pressure.

What are the guidelines and supportive data on using Colchicine?

- Colchicine 0.5 mg is the first FDA-approved anti-inflammatory therapy indicated for reducing cardiovascular events among adults who have established ASCVD or are at risk of developing it.

- The use of Colchicine is supported by the LoDoCo, LoDoCo-2, and COLCOT trials, which showed a ~25-30% risk reduction in cardiovascular risk. In comparison, studies using ezetimibe10 have shown a 6-7% relative risk reduction and PCSK9 inhibitors11 ~15% risk reduction for LDL reduction.

- LoDoCo12– in those with stable CAD, patients who received colchicine in addition to standard of care had a significantly lower composite rate of ACS compared to those who only received standard of care at a median follow-up of 3 years.

- LoDoCo-213– randomized control, multicentric trial in patients with stable CAD showing group randomized to colchicine + standard of compare had reduced MACE compared to those with placebo + standard of care at a median follow-up of 2.8 years.

- COLCOT14– Addition of colchicine within 30 days of ACS resulted in a reduction of the primary composite outcome of cardiovascular death, resuscitated cardiac arrest, MI, stroke, or urgent hospitalization for angina

What are examples of ongoing trials that will shape the future of our anti-inflammatory toolbox?

- ZEUS Trial15– ongoing trial that randomizes patients with ASCVD, hs-CRP ≥ 2 and CKD (eGFR between 15-60 OR EGFR ≥ 60 and urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio ≥200) to Ziltivekimab or placebo, and assesses time to first occurrence of MACE.

- Hermes HFpEF16– ongoing trial that randomizes patients with HFpEF and HFmrEF to Ziltivekimab or placebo, and assesses time to first occurrence of cardiovascular death, heart failure hospitalization, or urgent heart failure visit

- Artemis Acute Ischemia17– ongoing trial that randomizes patients hospitalized with MI to Ziltivekimab or placebo, and assess time to MACE.

- Clazakizumab in patients receiving maintenance dialysis18– this study randomized adults with known cardiovascular disease and/or DM2 receiving dialysis with hs-CRP ≥ 2 to receive Clazakizumab or placebo. The primary endpoint is a reduction in hs-CRP over 12 weeks.

References – Targeting Inflammation for Cardiovascular Risk

- Visser M, Bouter LM, McQuillan GM, Wener MH, Harris TB. Elevated C-Reactive Protein Levels in Overweight and Obese Adults. JAMA. 1999;282:2131-2135. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.22.2131

- Tonstad S, Cowan JL. C-reactive protein as a predictor of disease in smokers and former smokers: a review. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63:1634-1641. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02179.x

- Esteghamati A, Morteza A, Khalilzadeh O, Anvari M, Noshad S, Zandieh A, Nakhjavani M. Physical inactivity is correlated with levels of quantitative C-reactive protein in serum, independent of obesity: results of the national surveillance of risk factors of non-communicable diseases in Iran. J Health Popul Nutr. 2012;30:66-72. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v30i1.11278

- Anand SS, Razak F, Yi Q, Davis B, Jacobs R, Vuksan V, Lonn E, Teo K, McQueen M, Yusuf S. C-reactive protein as a screening test for cardiovascular risk in a multiethnic population. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1509-1515. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000135845.95890.4e

- La Grotta R, de Candia P, Olivieri F, Matacchione G, Giuliani A, Rippo MR, Tagliabue E, Mancino M, Rispoli F, Ferroni S, et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of SGLT-2 inhibitors via uric acid and insulin. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2022;79:273. doi: 10.1007/s00018-022-04289-z

- Mazidi M, Karimi E, Rezaie P, Ferns GA. Treatment with GLP1 receptor agonists reduce serum CRP concentrations in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Diabetes Complications. 2017;31:1237-1242. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2016.05.022

- Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Rifai N. C-reactive protein and other markers of inflammation in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:836-843. doi: 10.1056/nejm200003233421202

- Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, Genest J, Gotto AM, Jr., Kastelein JJ, Koenig W, Libby P, Lorenzatti AJ, MacFadyen JG, et al. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2195-2207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807646

- Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T, MacFadyen JG, Chang WH, Ballantyne C, Fonseca F, Nicolau J, Koenig W, Anker SD, et al. Antiinflammatory Therapy with Canakinumab for Atherosclerotic Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;377:1119-1131. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1707914

- Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, McCagg A, White JA, Theroux P, Darius H, Lewis BS, Ophuis TO, Jukema JW, et al. Ezetimibe Added to Statin Therapy after Acute Coronary Syndromes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372:2387-2397. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1410489

- Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, Honarpour N, Wiviott SD, Murphy SA, Kuder JF, Wang H, Liu T, Wasserman SM, et al. Evolocumab and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;376:1713-1722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1615664

- Nidorf SM, Eikelboom JW, Budgeon CA, Thompson PL. Low-dose colchicine for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:404-410. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.10.027

- Nidorf SM, Fiolet ATL, Mosterd A, Eikelboom JW, Schut A, Opstal TSJ, The SHK, Xu XF, Ireland MA, Lenderink T, et al. Colchicine in Patients with Chronic Coronary Disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1838-1847. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021372

- Tardif JC, Kouz S, Waters DD, Bertrand OF, Diaz R, Maggioni AP, Pinto FJ, Ibrahim R, Gamra H, Kiwan GS, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Low-Dose Colchicine after Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2497-2505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1912388

- ZEUS – Effects of Ziltivekimab Versus Placebo on Cardiovascular Outcomes in Participants With Established Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease, Chronic Kidney Disease and Systemic Inflammation. In; 2021.

- Effects of Ziltivekimab Versus Placebo on Morbidity and Mortality in Patients With Heart Failure With Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction and Systemic Inflammation. In; 2022.

- ARTEMIS – Effects of Ziltivekimab Versus Placebo on Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction. In: Duke Clinical Research I, ed.; 2023.

- Chertow GM, Chang AM, Felker GM, Heise M, Velkoska E, Fellström B, Charytan DM, Clementi R, Gibson CM, Goodman SG, et al. IL-6 inhibition with clazakizumab in patients receiving maintenance dialysis: a randomized phase 2b trial. Nature Medicine. 2024. doi: 10.1038/s41591-024-03043-1

6 November 2024, 10:50 pm - 8 minutes 40 seconds399. Guidelines: 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure – Question #37 with Dr. Clyde Yancy

The following question refers to Section 7.4 of the 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure.

The question is asked by the Director of the CardioNerds Internship Dr. Akiva Rosenzveig, answered first by Vanderbilt AHFT cardiology fellow Dr. Jenna Skowronski, and then by expert faculty Dr. Clyde Yancy.

Dr. Yancy is Professor of Medicine and Medical Social Sciences, Chief of Cardiology, and Vice Dean for Diversity and Inclusion at Northwestern University, and a member of the ACC/AHA Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines.

The Decipher the Guidelines: 2022 AHA / ACC / HFSA Guideline for The Management of Heart Failure series was developed by the CardioNerds and created in collaboration with the American Heart Association and the Heart Failure Society of America. It was created by 30 trainees spanning college through advanced fellowship under the leadership of CardioNerds Cofounders Dr. Amit Goyal and Dr. Dan Ambinder, with mentorship from Dr. Anu Lala, Dr. Robert Mentz, and Dr. Nancy Sweitzer. We thank Dr. Judy Bezanson and Dr. Elliott Antman for tremendous guidance.

American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions 2024

- As heard in this episode, the American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions 2024 is coming up November 16-18 in Chicago, Illinois at McCormick Place Convention Center. Come a day early for Pre-Sessions Symposia, Early Career content, QCOR programming and the International Symposium on November 15. It’s a special year you won’t want to miss for the premier event for advancements in cardiovascular science and medicine as AHA celebrates its 100th birthday. Registration is now open, secure your spot here!

- When registering, use code NERDS and if you’re among the first 20 to sign up, you’ll receive a free 1-year AHA Professional Membership!

Mr. S is an 80-year-old man with a history of hypertension, type II diabetes mellitus, and hypothyroidism who had an anterior myocardial infarction (MI) treated with a drug-eluting stent to the left anterior descending artery (LAD) 45 days ago. His course was complicated by a new LVEF reduction to 30%, and left bundle branch block (LBBB) with QRS duration of 152 ms in normal sinus rhythm. He reports he is feeling well and is able to enjoy gardening without symptoms, though he experiences dyspnea while walking to his bedroom on the second floor of his house. Repeat TTE shows persistent LVEF of 30% despite initiation of goal-directed medical therapy (GDMT). What is the best next step in his management?

A

Monitor for LVEF improvement for a total of 60 days prior to further intervention

B

Implantation of a dual-chamber ICD

C

Implantation of a CRT-D

D

Continue current management as device implantation is contraindicated given his advanced age

Explanation

Choice C is correct. Implantation of a CRT-D is the best next step.

In patients with nonischemic DCM or ischemic heart disease at least 40 days post-MI with LVEF ≤35% and NYHA class II or III symptoms on chronic GDMT, who have reasonable expectation of meaningful survival for >1 year,

ICD therapy is recommended for primary prevention of SCD to reduce total mortality (Class 1, LOE A). A transvenous ICD provides high economic value in this setting, particularly when a patient’s risk of death from ventricular arrhythmia is deemed high and the risk of nonarrhythmic death is deemed low.

In addition, for patients who have LVEF ≤35%, sinus rhythm, left bundle branch block (LBBB) with a QRS duration ≥150 ms, and NYHA class II, III, or

ambulatory IV symptoms on GDMT, cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) is indicated to reduce total mortality, reduce hospitalizations, and improve symptoms and QOL. Cardiac resynchronization provides high economic value in this setting.

Mr. S therefore meets criteria for both ICD and CRT.

Choice A is incorrect. All patients should be on maximally tolerated doses of GDMT prior to consideration of device implantation to allow for assessment of LVEF recovery. Patients who have experienced myocardial infarction should be reassessed 40 days after the event and after achieving maximally tolerated doses of GDMT.

Choice B in incorrect. For patients in sinus rhythm with a LBBB morphology and QRS duration >150 ms with an LVEF ≤35%, there were significant improvements in 6-minute walk test performance, quality of life, NYHA classification, and LVEF after implantation of CRT. Mortality and hospitalizations were also found to be decreased in patients with CRT-P & CRT-D. Overall, CRT has been shown to have high economic value in these patients.

It should be noted that CRT has the most benefit in patients with a wide QRS (>150 ms), LBBB morphology, and LVEF ≤35%, though trials have shown a modest benefit in special populations. CRT has a Class 2a recommendation (LOE B-NR) in patients with LVEF ≤35%, sinus rhythm, and NYHA Class II, III, or ambulatory IV symptoms on GDMT, with either:

a) Non-LBBB pattern with a QRS duration ≥150 ms

b) LBBB with a QRS duration of 120 to 149 ms

Choice D is incorrect. If LVEF remains ≤35% in a patient with a life expectancy >1 year, trials have shown that ICD placement for primary prevention reduces sudden cardiac death and also has a high economic value. There is no indication that this patient has a life expectancy < 1 year.

Main Takeaway

In patients 40 days post-MI on GDMT with an LVEF that remains ≤35%, ICD therapy for primary prevention is appropriate and cost effective. For those additional with a LBBB and QRS >150 ms, CRT-D is also appropriate and cost effective.

Guideline Loc.

Section 7.4

Decipher the Guidelines: 2022 Heart Failure Guidelines Page

CardioNerds Episode Page

CardioNerds Academy

Cardionerds Healy Honor RollCardioNerds Journal Club

Subscribe to The Heartbeat Newsletter!

Check out CardioNerds SWAG!

Become a CardioNerds Patron!5 November 2024, 1:09 am - 35 minutes 38 seconds398. Narratives in Cardiology: Career Flexibility in Cardiology with Dr. Minnow WalshIn this episode, Dr. Gurleen Kaur (Cardiology FIT at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and APD of the CardioNerds Academy) and Dr. Diane Masket (Medicine Resident at the University of Chicago Northshore and CardioNerds Academy Intern) discuss with Dr. Minnow Walsh (Medical Director of the Heart Failure and Cardiovascular programs at Ascension St. Vincent Heart Center in Indianapolis) about her personal and professional journey in Cardiology. They discuss Dr. Walsh’s authorship of the recent ACC statement on career flexibility in Cardiology, her involvement with the ACC at both the local and national levels, and her passion for making cardiology a more inclusive and welcoming field for all. Notes were drafted by Dr. Diane Masket and episode audio was engineered by student Dr. Grace Qiu. The PA-ACC & CardioNerds Narratives in Cardiology is a multimedia educational series jointly developed by the Pennsylvania Chapter ACC, the ACC Fellows in Training Section, and the CardioNerds Platform with the goal to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion in cardiology. In this series, we host inspiring faculty and fellows from various ACC chapters to discuss their areas of expertise and their individual narratives. Join us for these captivating conversations as we celebrate our differences and share our joy for practicing cardiovascular medicine. We thank our project mentors Dr. Katie Berlacher and Dr. Nosheen Reza. The PA-ACC & CardioNerds Narratives in Cardiology PageCardioNerds Episode PageCardioNerds AcademyCardionerds Healy Honor Roll CardioNerds Journal ClubSubscribe to The Heartbeat Newsletter!Check out CardioNerds SWAG!Become a CardioNerds Patron! Video version - Career Flexibility in Cardiology https://youtu.be/ygNH6fcQ5ek Quoatables - Career Flexibility in Cardiology “You have to learn to live with ambivalence. You can’t do everything. You can’t do everything all at one time” “One of the most important things the College is behind and pushing, is that competency-based evaluation is what should be used in fellowship rather than this sort of cookie cutter approach where you have to do these many months of echo and this much of cath lab. So, I think flexibility moving from volume to competency is one push.” “Fellowship is daunting, and internal medicine residency is too, but I think culture is how we feel every day. And I think the more we increase flexibility the more that culture is going to shift. Notes - Career Flexibility in Cardiology Process of developing ACC Health Policy Statements These documents address issues that require ACC influence and usually involve a variety of institutions, governing bodies, and other stakeholders. ACC comes to an agreement on how they will approach this topic and shares it broadly. Most of the existing ACC health policy statements are disease-based instead of profession-based. The ACC Career Flexibility statement grew out of the diversity, equity, and inclusion task force, which is a standing committee. A variety of authors are included in health policy statements to reflect the perspectives of many different interest groups. All policy statements, including the one about career flexibility, are available online on JACC.org 1 Major Components of the ACC Career Flexibility Health Policy Statement There are 18 principles that highlight the most important aspects regarding career flexibility in cardiology.2 Flexibility allows for deceleration (decrease in work hours, responsibilities, etc.) and acceleration based on the needs of the physician. For example, during childbearing and rearing time periods, there could be a deceleration, which could accelerate when parenthood responsibilities have decreased. It does not only need to be based around parenting; physicians who are not parents also desire flexibility and enjoy spending time on activities other than their careers. These needs will be unique for each person.31 October 2024, 3:01 pm

- More Episodes? Get the App

Your feedback is valuable to us. Should you encounter any bugs, glitches, lack of functionality or other problems, please email us on [email protected] or join Moon.FM Telegram Group where you can talk directly to the dev team who are happy to answer any queries.

The Curbsiders Internal Medicine Podcast

The Curbsiders Internal Medicine Podcast

Eagle's Eye View: Your Weekly CV Update From ACC.org

Eagle's Eye View: Your Weekly CV Update From ACC.org

Core IM | Internal Medicine Podcast

Core IM | Internal Medicine Podcast

The Clinical Problem Solvers

The Clinical Problem Solvers

JACC Podcast

JACC Podcast

This Week in Cardiology

This Week in Cardiology