Pasha - from The Conversation Africa

The Conversation

Welcome to Pasha, The Conversation Africa’s brand new podcast. In the spirit of The Conversation, Pasha – which means to inform in Swahili – will be bringing you some of the best and brightest research from academics across the continent. After nearly four years of publishing expert research, we’re thrilled to be bringing our own brand of smart journalism to a new audio format. Each episode will collect stories and commentary on a given theme.

- 13 minutes 38 secondsHow the pandemic lockdown in South Africa affected mental health

shutterstock

shutterstock When SARS-CoV-2 emerged in South Africa, the country took measures to restrict people’s movements and activities, to slow the spread of infections. There were various levels of restrictions, the most severe being in place in March and April 2020.

During this “hard lockdown”, many people in South Africa really struggled. Not only did they have financial difficulties but the lockdown took an emotional and mental toll. The common themes, no matter where people lived, were feelings of anxiety, frustration and isolation. And as lockdown went on, those feelings got worse.

In today’s episode of Pasha, Sarita Pillay, a PhD student at the University of the Witwatersrand, and Miriam Maina, a research associate at the University of Manchester, take us through their research on this lockdown toll.

The researchers got their information from multimedia diary entries made during the “level 5” lockdown. Their informants were people living in a variety of dwelling types, households and urban neighbourhoods. The entries recorded participants’ daily experiences, concerns and feelings.

Much of the anxiety people felt came from the fact that it was an unknown virus. People didn’t know how it would affect them. They also worried about people breaking lockdown regulations. The economic impact of the lockdown was a concern; food security was a big issue.

Feelings of isolation and frustration came from being alone. It didn’t help that people were separated from their daily routines.

Photo “Empty streets in the city of Cape Town during the lockdown for Covid-19” by fivepointsix found on Shutterstock.

Music “Happy African Village” by John Bartmann, found on FreeMusicArchive.org licensed under CC0 1.

“Back To My Roots” by John Bartmann, found on Freesound licensed under Attribution 4.0 International License.

18 August 2022, 8:15 am

18 August 2022, 8:15 am - 15 minutes 13 secondsWhat’s wrong with the Fourth Industrial Revolution

shutterstock

shutterstock The “Fourth Industrial Revolution” is a term coined in 2016 by German economist Klaus Schwab. It’s used to describe the technology revolution that the world is going through. But there is growing criticism, particularly in the global south, of how it’s framed. Many are questioning whether it should be considered a revolution at all.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution, according to one view, is a very simplistic narrative that advances a distinct political agenda. It is a kind of exploitation that is being sold as progress. The narrative is being advanced to achieve a specific economic outcome – at the expense of many people in the global south.

Many innovations are happening in the digital technological space. But do they reorganise production and social relations, or do they just entrench past forms of inequality?

Consider the case of the ride-hailing app Uber. It may sound like enticing work for drivers, but there’s more to it. Drivers may face bad working conditions, penalties and other challenges without the security of human resources behind them.

In this episode of Pasha, Ruth Castel-Branco, manager of the Future of Work(ers) research project at the University of the Witwatersrand, joins Nanjala Nyabola, a storyteller and political analyst, in taking us through the seductive idea of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Read more: The Fourth Industrial Revolution: a seductive idea requiring critical engagement

Photo “A smartphone attached to the dash on a vent holder in a moving Uber car. The Uber App shows the route in Cape Town map.” by maurodopereira, found on Shutterstock.

Music “Happy African Village” by John Bartmann, found on FreeMusicArchive.org licensed under CC0 1.

“African Moon” by John Bartmann, found on FreeMusicArchive.org licensed under CC0 1.

10 August 2022, 2:34 pm

10 August 2022, 2:34 pm - 11 minutes 43 secondsTips for parents on keeping kids safe online

GettyImages

GettyImages Young children and adolescents are becoming hyper connected. They are using digital technologies as a platform for learning, connection and socialisation on a global scale. The COVID pandemic meant that kids were moving online for many of their daily activities and spending more time online.

In South Africa, children generally access the internet at home much more frequently than at school, and most commonly using a smartphone. Their main online activity is use of social media.

Connecting online has the potential to reduce inequalities and barriers to education and services. But there is also a risk of exposure to a range of threats. In one survey, about 50% of South African adolescents had been exposed to sexual content and 34% also reported exposure to violent content and hate speech.

Not all exposure is risky or damaging. But what can parents do to monitor their children’s use of the internet and protect them from potential harm?

The answer lies in finding the right balance between empowerment and protection. The internet is here to stay. Parents should engage with their children on the digital world. The quality of offline relationships and communication is the key to protecting children online.

In today’s episode of Pasha, Rachana Desai, a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of the Witwatersrand, offers some tips:

Download the apps that your child frequently uses and understand why your child enjoys them.

Ask your child to teach you how to use the technology they use. This is a great communication and interaction activity because children often like to teach their parents and it’s quite empowering for them.

Friend your child on social media platforms – with boundaries. Do it in such a way that they still have their own space to express themselves.

Talk to your child about their experiences online. Ask them open ended questions like whether there was anything that bothered them online. You want to get to know what’s going on without over-supervising and then having your child completely isolate you from the online world.

Read more: Children's mental health and the digital world: how to get the balance right

Photo “Happy boy taking a break watching a portable tablet with earphones” by Hello Africa, found on Getty Images.

Music “Happy African Village” by John Bartmann, found on FreeMusicArchive.org licensed under CC0 1.

“Ambient guitar X1 - Loop mode” by Frankum, found on Freesound licensed under Attribution License.

3 August 2022, 4:03 pm

3 August 2022, 4:03 pm - 14 minutes 46 secondsKiller whales are hunting great white sharks in South Africa’s waters

shutterstock

shutterstock Great white sharks have long been at the top of the food chain in parts of South Africa’s oceans. In their peak winter hunting months, around 100 great white sharks a day could be observed off the coast of the Western Cape province. But in 2017, great white shark carcasses began to wash up on beaches at Gansbaai, one of the main sites where the species usually gathered. Some were missing their livers. And the numbers of great white sharks in Gansbaai started to drop. In fact, they just vanished for up to a year at a time. What was the cause?

The culprits appear to be a pair of male killer whales, which researchers have named Port and Starboard, that arrived in the area. They have a signature way of tearing open their prey and they favour the nutrient-rich liver.

Port and Starboard. David Hurwitz

Though killer whales are known to hunt sharks far from shore elsewhere in the world, this was the first time the carcasses had washed up on a beach and become available for scientific study.

In today’s episode of Pasha, shark biologist and PhD candidate Alison Towner tells the unfolding story of the impact the killer whales are having on South Africa’s marine ecosystems. Great white sharks are fleeing to other parts of the coast and their absence affects other species like African penguins and Cape fur seals.

Tami Kaschke, Dyer Island Conservation Trust

It’s a novel situation, with concerns for the tourism and conservation sectors – and no simple answers.

Photo “Great white shark” by Mogens Trolle, found on Shutterstock.

Music “Happy African Village” by John Bartmann, found on FreeMusicArchive.org licensed under CC0 1.

“African Moon” by John Bartmann, found on FreeMusicArchive.org licensed under CC0 1.

Sounds “orcas (killer whales)” by MBARI_MARS found on Freesound licensed under attribution noncommercial 3.0 license.

13 July 2022, 2:00 pm

13 July 2022, 2:00 pm - 12 minutes 41 secondsSnare and shotgun injuries reveal more about threats to lions and leopards in Zambia

GettyImages

GettyImages Wildlife and people are coming into more and more conflict across Africa as human populations expand. Habitat loss and fragmentation of animal populations are causing declines in species.

In Zambia, the Luangwa Valley and Kafue are two important wildlife areas. Both support populations of lion and leopard which are genetically linked to populations in neighbouring countries. They have great conservation value and are crucial for Zambia’s tourism industry too.

It was here that Paula White, director of the Zambia Lion Project at the University of California in the US, noticed something strange while researching the conservation of carnivores. Looking at the skulls of lions and leopards to estimate the animals’ ages, she saw unnatural wear marks on the teeth of these big cats. This was caused by biting and pulling on snare wire to get free. What is more, many of the lions had old shotgun pellets embedded in their skulls. They had survived these injuries – but how many more animals had not?

Behind the threat to the lions and leopards are complex social and economic issues. People move to where there are opportunities to make a living – from wildlife tourism and associated economic activity, for example. This can bring them into conflict with animals. Some people set snares because they need food, not necessarily to catch carnivores. And they may fire shotguns to drive off predators, not to kill them.

It is vital to understand the complexities of these relationships. People who live close to parks need to receive the benefits of wildlife, as our guest explains in today’s episode of Pasha.

Photo: “Portrait Of Lion Standing On Grassy Field, Kasempa, Zambia” by Stock Photo Getty Images.

Music: “Happy African Village” by John Bartmann, found on FreeMusicArchive.org licensed under CC0 1.

“Somewhere Nice” by John Bartmann, found on FreeMusicArchive.org licensed under CC0 1.

25 May 2022, 1:31 pm

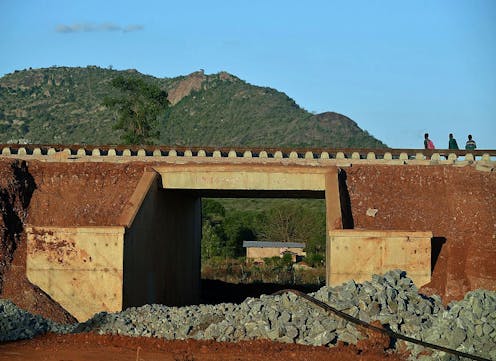

25 May 2022, 1:31 pm - 12 minutes 21 secondsBig infrastructure projects on the continent should work for everyone

GettyImages

GettyImages Big infrastructure projects should be based on the needs of people and communities. Often, they are criticised for benefiting the wealthy only. These projects reflect specific agendas of political and economic elites who are able to advance their interests through the developments. They interplay with existing inequalities and almost inevitably have highly uneven effects.

An example is Kenya’s Standard Gauge Railway, a massive infrastructure project that connects the port city of Mombasa to the capital, Nairobi.

So how can these projects be made beneficial to more people? Civil society groups are crucial to ensuring equity. They have the power to reach marginalised groups and can educate them about projects and about their rights. It is also important to make sure projects don’t become a political tool.

In today’s episode of Pasha, Gediminas Lesutis, a Marie Curie Fellow at the University of Amsterdam, talks about making massive infrastructure projects work for communities.

Read more: Kenya’s mega-railway project leaves society more unequal than before

Photo: “Children walk by the rails at an elevated section of the new Standard Gauge Railway in Kenya” By Tony Karumba/AFP via Getty Images

Music “Happy African Village” by John Bartmann, found on FreeMusicArchive.org licensed under CC0 1.

“African Moon” by John Bartmann, found on FreeMusicArchive.org licensed under CC0 1.

15 May 2022, 7:16 am

15 May 2022, 7:16 am - 10 minutes 54 secondsBig development projects can have negative effects on nature and people

There are some major development projects in progress on the continent. They include the Standard Gauge Railway in Kenya and irrigation and hydropower projects in Tanzania’s Rufiji Basin. Projects like these have potential to change people’s lives for good. But they also come with risks.

Some big projects damage environments by disturbing the habitats of wildlife like lions and elephants. In Kenya the rail project has displaced these animals so that they come into conflict with people. Construction can also bring in and spread invasive species. Some projects can lead to an increase in illegal logging, poaching and fires. Or they can have an impact on the ecosystems of rivers, coasts or oceans.

Negative impacts can extend to communities through loss of livelihoods or exposure to natural hazards like flooding or erosion. One major criticism is that big development projects benefit wealthy people but don’t help poorer communities. They can widen huge socioeconomic disparities.

It is also important to make sure that projects consider how infrastructure might operate under a changing climate in the future. There might be much higher temperatures, higher variability in rainfall, and higher frequency of floods and droughts.

Today’s episode of Pasha takes a look at major infrastructure projects on the continent from a variety of perspectives. Our guests are biodiversity researcher Tobias Nyumba, climate change modeller Jessica Thorn, political analyst Gediminas Lesutis and geographer Declan Conway.

Photo: Impalas walk near the elevated railway that allows movement of animals below the tracks at the construction site of Standard Gauge Railway in Nairobi National Park, Kenya, on November 21, 2018. Photo by Yasuyoshi Chiba/AFP via Getty Images.

Music: “Happy African Village” by John Bartmann, found on FreeMusicArchive.org licensed under CC0 1.

“Ambient guitar X1 - Loop mode” by frankum, found on Freesound licensed under Attribution License.

Sounds: “Peaceful farm ambiences in spring” by be_a_hero_not_a_patriot found on Freesound licensed under Creative Commons 0 License.

“Flooding” by tarane468 found on Freesound licensed under Attribution 3.0 License.

20 April 2022, 2:05 pm

20 April 2022, 2:05 pm - 6 minutes 47 secondsProjects like Kenya’s Standard Gauge Railway can unlock development

shutterstock

shutterstock Kenya’s Standard Gauge Railway, which links Nairobi and Mombasa, East Africa’s largest port, was built to ease the pressure on the road network. Construction started in 2013 and was completed in 2017, with an extension in 2019. The line transports passengers as well as cargo. It makes the trip between the cities safer and shorter.

The project is also being promoted as a means to develop Kenya’s mining, oil, gas, energy and commercial agriculture sectors as well as the wider East African region. It aims to link Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi and South Sudan to the Indian Ocean trade routes to the east.

Projects like this are known as development corridors and have the potential to bring major socioeconomic benefits. Access to jobs and markets, efficient transport, cheaper food and opening up isolated areas are among them.

In today’s episode of Pasha we bring you the first episode in a series we’re running on development corridors. This episode looks at the positive aspects of such initiatives. Our guest this week is Jessica Thorn, a research associate with the Development Corridors Partnership between Tanzania, Kenya, China and the UK.

Photo:

“View of the Mombasa-Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway Bridge through the Nairobi National Park Nature Reserve near Nairobi, Kenya” by schusterbauer.com found on Shutterstock.Music: “Happy African Village” by John Bartmann, found on FreeMusicArchive.org licensed under CC0 1.

“Gimme That African Vibe” by John Bartmann found on FreeMusicArchive.org licensed under Attribution 4.0 International License..

Sounds: “South African train” by Deathicated found on Freesound licensed under Attribution License.

11 April 2022, 1:46 pm

11 April 2022, 1:46 pm - 9 minutes 56 secondsWhen a hippo honks, here’s what it could mean – to another hippo at least

shutterstock

shutterstock Hippos are very vocal animals, exchanging signals like the “wheeze honk”. But not much is known about what these sounds mean. Two researchers found themselves thinking about this in Mozambique – where they were initially studying crocodiles.

Hippos are quite territorial and aggressive – and fast-moving. So the researchers kept a fair distance away as they conducted their experiment. They recorded hippo noises and played them back to the animals, watching to see how the hippos behaved. If the call came from an unknown hippo in a different social group, the response appeared to be aggressive. If the call was one they recognised, they were less inclined to be aggressive.

One way hippos show aggression is to spray dung.

The meaning of hippo sounds is useful to know for conservation efforts. Hippos and humans sometimes come into conflict and need to be moved for their own survival. Before relocating them, conservation managers could play them the sounds of the hippos they will be meeting in their new location, to familiarise them.

In this episode of Pasha, Nicolas Mathevon, professor in animal behaviour and bioacoustics at the University of Saint-Etienne, and Paulo Fonseca, professor in acoustic communication at the University of Lisbon, take us through their experiences of listening to hippos in Mozambique.

Photo “Specie Hippopotamus amphibius family of Hippopotamidae.” by PACO COMO, found on Shutterstock

Music “Happy African Village” by John Bartmann, found on FreeMusicArchive.org licensed under CC0 1.

“African Moon” by John Bartmann, found on FreeMusicArchive.org licensed under CC0 1.

The researchers would like to thank the Maputo special reserve for allowing them to do the research on the property.

1 March 2022, 3:04 pm

1 March 2022, 3:04 pm - 23 minutes 28 secondsCities must listen to people to find solutions for climate impacts: stories from Cape Town

shutterstock

shutterstock A few years ago the South African city of Cape Town was close to reaching “day zero” – the day the taps would run dry as a result of a serious drought. Households had to restrict their water usage, water tariffs increased, and businesses had to rethink how they used water. But the situation affected people unequally. Households experienced it in different ways. The poor and vulnerable suffered the most.

With the changing climate, problems like these aren’t going anywhere. Water scarcity, higher temperatures and changing rainfall patterns will become more common, so finding ways to adapt is important. And in a city where inequality and financial pressures are deep and complex, adaptive change will take time.

It also takes information. For city planners and decision makers, data is essential – but not just quantitative data. They need to engage with people to understand how they experience issues like water scarcity.

Making sense of a water crisis.In today’s episode of Pasha, two researchers discuss their work on inequality in water and describe a project that brought city authorities and community members together. Gina Ziervogel is in the Department of Environmental and Geographical Science and Johan Enqvist is with the African Climate and Development Initiative, both at the University of Cape Town.

Photo: “Lines of people waiting to collect natural spring water for drinking in Newlands in the drought in Cape Town South Africa.” Photo by Mark Fisher Shutterstock.

Music: “Happy African Village” by John Bartmann, found on FreeMusicArchive.org licensed under CC0 1.

“Ambient guitar X1 - Loop mode” by frankum, found on Freesound licensed under Attribution License.

Video: “Making sense of a water crisis” filmed by Odendaal Esterhuyse

14 February 2022, 2:53 pm

14 February 2022, 2:53 pm - 9 minutes 53 secondsTechnology for education has huge potential: partnerships can widen access

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted normal contact learning in education systems worldwide. Technology became an essential tool for learning and it has great potential beyond the pandemic. For one thing, it enables more interactivity than some old styles of teaching.

But there are a number of barriers to using technology more widely in education. Users need data, a device and a learning management system. They need training in the skills to learn and teach online, and support for troubleshooting. Internet access may be seen as a human right, but Africa’s digital divide means that in reality not everyone can equally exercise that right. Some people are more connected than others.

Radio and television are also useful technologies in widening access to education but they mostly require electricity, which isn’t universally available either.

In today’s episode of Pasha, vice-chancellor and principal Tawana Kupe shares what the University of Pretoria in South Africa did to make online learning possible for all its students. He calls for public-private partnerships to develop internet infrastructure so that everybody can have access. And he makes the case for an internet-empowered education system at all levels.

Photo “Hands of a little girl child working or typing on a laptop’s keyboard.” by Kehinde Olufemi Akinbo, found on Shutterstock

Music “Happy African Village” by John Bartmann, found on FreeMusicArchive.org licensed under CC0 1.

“African Moon” by John Bartmann, found on FreeMusicArchive.org licensed under CC0 1.

6 February 2022, 8:33 am

6 February 2022, 8:33 am - More Episodes? Get the App

Your feedback is valuable to us. Should you encounter any bugs, glitches, lack of functionality or other problems, please email us on [email protected] or join Moon.FM Telegram Group where you can talk directly to the dev team who are happy to answer any queries.

The Daily

The Daily

Today in Focus

Today in Focus

The Dropout

The Dropout

The Intelligence from The Economist

The Intelligence from The Economist

TED Talks Daily

TED Talks Daily

Speaking with...

Speaking with...