Q&A Coffee Podcast with Scott Rao

Scott Rao

Beginner and advanced questions about coffee brewing and roasting.

- ADVANCED HOOPING

Now that I’ve used the Ceado Hoop brewer for several months, I have a few tips to share with readers. Although the Hoop produces beautiful extractions more easily than any other brewer, every brewer has a few quirks to be mindful of when brewing.

Filter Paper

Before I began offering upgraded filter paper for the Hoop, the original paper’s flow restriction and tendency to clog forced Hoop users to use a very coarse grind. Some grinders can’t grind coarse enough to prevent stalls with the original paper.

The upgraded paper allows one to use a grind setting similar to what one would use for a larger-dose pourover or a NextLevel Pulsar to produce 4:00 brews with a 22g dose. Please remember to always mount the filter in the Hoop with the rough side up. The rough side of the filter has extra surface area, which allows it to trap far more fine particles without clogging. The paper from NextLevel is the best I’ve ever tried: it has smaller holes for good clarity, with ample surface area for trapping fines and limiting clogging. These filters turn the Hoop from a finicky brewer into one of the two the best manual brewer on the market (along with the Pulsar).

Breaking the Crust

I recommend generally avoiding agitating, swirling, stirring, or shaking the Hoop while brewing. Less agitation helps prevent clogging and uneven extractions. The one exception is if a dry crust of grounds forms at the top of the slurry when brewing fresher or darker roasts. The larger the crust, the fewer grounds that are in the intact coffee bed. At the extreme, a large crust can lead to low extractions. To break the crust, I recommend using a WDT Tool to gently stir the grounds until they submerge.

Pouring

While you *can* get a great brew by pouring the water rapidly into the outer ring of the Hoop, I find overall better results from pouring slowly, moving the kettle side to side to prevent the water from swirling in one direction. I tend to pour the first 1/3 of the water slowly, and then pour the rest quickly.

Water

I recommend pouring water just off the boil. While there are many things I could say about optimal water chemistry, the most important consideration — by far — is that the alkalinity (aka KH, bicarbonate, buffer) is at a reasonable level. I recommend alkalinity of 25—40 ppm. While hardness matters, the Hoop is not at risk of scaling, and one has a wide range of acceptable hardness levels to yield delicious coffee. Hardness of 30—90 ppm (CaCO3 equivalent) should work well, as long as there is at least a modest level of magnesium in the water. In cases of near-zero magnesium, I recommend adding 3-4 drops of Lotus Magnesium Chloride to each brew, before or after brewing.

Level

Hoop users know that unfortunately the Hoop does not sit flat on all carafes. I recommend trying this if you want to use a glass carafe with the Hoop, or this if you want a stainless steel carafe.

Stalled Brews

If your brew stalls, please first try grinding coarser, even if the grind setting seems unreasonable to you. If the coarsest setting on your grinder still causes brews to stall, or yields brews that are too weak, please consider these factors:

Make sure you are using my upgraded filter paper and have inserted the filter rough-side-up

You can try a smaller dose, but I recommend not using less than 18 grams

Decrease or eliminate any source of agitation

Check that your grinder burrs are not dull or poorly aligned. Please note that just because your pourovers don’t stall easily, that doesn’t mean the burr sharpness or alignment isn’t the problem with the Hoop; it is possible your pourover brews have an exceptional amount of bypass. Most “espresso” or “Turkish” burrs will not work well with the Hoop, and are generally not appropriate for filter brewing.

If you try all of the above and your Hoop still stalls, please drop a comment below, and I will help you troubleshoot.

14 December 2024, 6:31 am - A Deep Dive into Cup of Excellence

My sincere thanks to Peter Jones of Idle Hands Roasting and Trident Cafe, and to Benjamin Paz of Beneficio San Vicente, for their help with this post. If you enjoy this post and want to help increase awareness of Cup of Excellence, please share this post. Thank you.

Cup of Excellence is a competition of coffee quality held annually in numerous producing countries. Each competition involves six rounds of evaluation, a national jury, and an international jury. Cup of Excellence was founded by George Howell, Susie Spindler, and Silvio Leite in 1999. The first competition was held in Brazil, and the program has since expanded to sixteen producing countries.

Why I love Cup of Excellence

I love Cup of Excellence for many reasons: the competition promotes improved coffee quality, winners (those who qualify for the auction) receive very large price premiums for their coffees, COE incentivizes investment in quality, it connects buyers and sellers, and it rewards fantastic work. COE also does a lot to validate and recognize coffee quality in a way that helps grow the market for premium specialty coffee. We support COE at Prodigal because it is one of the few initiatives I’m aware of that fosters many unambiguous, positive outcomes for everyone involved. In the words of my friend Peter Jones, who has judged numerous COE competitions, “winning changes people’s lives.”

They’re not messing around

Years ago, I thought COE was simply a competition involving high-quality coffee. I drastically underestimated the depth, complexity, and impact of the competition: by the time the competition is over, approximately 8700+ cups will have been tasted and scored by the judges, volunteers will have given thousands of hours of their time to the competition, and the competition will have changed many lives.

A tremendous amount of effort goes into making each COE competition a success. About 40 volunteers each spend a week or two working hard to make a competition run smoothly. The national jury gives several days of their time to cup and score hundreds of coffees several times each. The international jury pay for their own flights and volunteer a week of their lives to each competition. Entire families, and often many neighbors from a producer’s community, will travel to the event to support a producer whose coffee is in the competition.

COE is open to all farmers in a given country. Each farmer may enter one sample at no cost. All coffees are cupped “blindly”, meaning judges do not know the name of the farmer, the farm, or the varieties of the coffees on the table. To qualify and advance in the competition, a sample must score at least 86 points.

slides courtesy of Scott Conary of Carrboro Coffee Roasters

Judging

The national jury is made up of experienced cuppers from the country of origin. This jury cups all of the coffees entered at pre-selection, and samples that score 86 or higher advance to the national jury week. After the national jury whittles the number of qualifying coffees down to 40, the judging is passed on to the international jury.

The international jury is made up of cuppers from both producing and consuming countries. Each judging panel spends one full day doing extensive calibration. To become a member of an international jury, a judge must take a standardized sensory training, participate in COE as an “observer” judge, and successfully calibrate his or her scores with those of experienced judges.

National Jury Day One (Calibration)Before the competition begins, an in-country organization, such as the producing country’s SCA chapter, collects the samples entered into the competition. The head judge flies in and selects the national jury of 20 judges. The head judge spends a full day calibrating the national jury. On calibration day, the judges cup three tables of 10 coffees, with each coffee duplicated on the other side of the table. This process is repeated twice. Judges are expected to be consistent in how they score the duplicate cups, and to show a dynamic range in their scores, especially for a few outlier (non-competition) coffees added to the calibration tables.

National Jury Day Two (pre-selection)

On day one of the competition, the judges cup each sample four times, with typically 300 or more samples submitted to the competition. Cups must score an average of 86 points or higher to advance in the competition, with a maximum of 150 samples moving on to the next round.

After samples have passed round one, the producers must move their entire lots to a bonded warehouse overseen by an independent auditor. Samples cupped in successive rounds are drawn from these lots.

National Jury Day Three

The national jury cups the samples that passed the pre-selection round. A maximum of 90 samples advance to round three. Samples must again score 86 or higher to reach the next round.

National Jury Day Four

Judges cup the samples, choosing a maximum of 40 samples to advance to the international jury.

International Jury Day One:

All-day calibration

International Jury Day Two & Three

The international jury cups the samples and decides which will be awarded the “Cup of Excellence” label. Those 30 lots will enter the auction, and the scores for places 11—30 are now finalized.

International Jury Day Four

On the final day of the international jury, the judges re-cup the ten highest-scoring samples to give them extra scrutiny and finalize their scores and ranking. This day is fun for the judges, as the hard work of intense cupping is behind them, and they get to enjoy cupping ten beautiful coffees at a relaxed pace. Peter Jones told me there is a nice tradition of the international judges tipping the volunteers at the end of the competition.

International Jury Day Five

Day five is the big reveal and party. Paraphrasing Peter: “it’s emotional; government officials come, farmers and their families, and sometimes their neighbors, come, and all of the winners get a plaque and a certificate. Everyone is very supportive, cheering on farmers, and you can see and feel the emotions of everyone involved. Everyone goes crazy when they reach the top three, and people are crying and cheering. You can tell the farmers’ lives are changed by placing in the competition.”

The AuctionAbout five or six weeks after the competition, the top 30 lots are sold in an internet auction. Competition lots that scored above 85 but did not reach the top 30 qualify for the National Winners Auction.

COE Cupping form

Impact

A Technoserve report from 2015 of COE’s impact in Brazil and Honduras found impressive direct and indirect benefit to producing communities and concluded COE acted as a catalyst for specialty-coffee industry growth in participating countries. COE competitions have promoted direct trade, helped forge new relationships between buyers and producers, and promoted specialty coffee growth in new markets, especially in Asia.

According to the report “the premiums paid by COE are several times higher than prevailing specialty and direct trade prices. These high premiums encourage producers to enter a beneficial cycle of improved quality, greater recognition for specialty coffee, and greater demand….The indirect benefits from COE are estimated to be more than $100 million for Brazil and $22 million for Honduras (and are included in the total benefit cited above).”

Presumably, nine years later, the economic impact of COE in those countries is now far greater than it was at the time of the report.

A Producer’s Perspective.

I asked Benjamin Paz of Beneficio San Vicente to tell me a little about his experience with COE, and his perspective on the benefits of the competition. Benjamin began working with farmers in 2005-2006 to help them place well in COE. In 2011, Benjamin bought his own farm, and has placed many times in the COE competition. Benjamin’s coffee came in first place in 2022 and 2024!

Benjamin says participating in COE has generated a lot of interest in San Vicente, and Santa Barbara coffees in general, not just in the farms that have placed well in the competition. That may be the true virtue of COE: rewarding hard work by bringing attention to farmers and regions producing amazing coffee.

One example of COE focusing attention where it belongs happened in 2015. Benjamin cupped a new hybrid variety that wasn’t very popular at the time. He recommended the producer submit the coffee to COE, despite others saying it would not do well. That coffee, the first parainema to enter COE, came in first place :). Personally, I have loved the few parainemas I have tasted, and understand what Benjamin saw in that coffee.

Prodigal is a proud participant in Cup of Excellence

Because we greatly admire the Cup of Excellence program, we have already purchased lots in several recent COE auctions, and hope to purchase lots from many more in the future. This week we released two Ethiopian COE winners and lots on the way from the Best of Rwanda and other COE competitions.

13 November 2024, 10:17 pm - Color Measurement: Best Practices

Given that coffee color is the best predictor of flavor, color measurement is a useful tool in roasting quality control. There are many color meters on the market with similar utility. I don’t have a strong preference for a particular color meter, but would like to offer a short guide to ensuring accurate color measurement.

When purchasing a color meter, there are a few considerations:

How consistent and accurate is the device?

How easy is it to use?

What is the cost?

What amount of ground coffee is required for a ground-color measurement?

Sample tray size

I think the last factor is the most underappreciated: some devices require upwards of 100g to take a color measurement. While a larger dose can provide more surface area, which offers more stable and representative measurements, it also wastes a lot of coffee. A roastery measuring 100 batches per week, at 100g per sample, at an average cost of $10/kg (roasted) coffee would spend approximately $5,000 per year taking ground color measurements! The same roastery using a color reader that requires 5g per sample would spend $250 per year on ground-coffee measurement.Most people in the market for a color reader fixate on trying to save a few hundred dollars when purchasing a color meter, but don’t factor in that purchasing one meter vs another may cost an extra $48,000 over the next ten years.

Of course, using a very small sample tray has a downside, which is that readings are more volatile. For example, we use a DiFluid Omni, which has a very small sample tray and requires about 5g per ground sample. One quaker can alter the color reading by a few points. In a larger tray such as that of the Agtron or ColorTrack, there will be less variability in the readings. We compensate for this variability by taking a few readings if the first reading is not what we expect it to be. Note: I don’t mean “our reading is out of our target range.” I mean “we expected the reading to be x based on the roasted weight loss, but the reading is x+4.”

Grinding

Grind size has a shocking impact on color measurement. For example, we have an EK with setting from 1–11. When we grind on #1, the color reading is ~25 points higher than when we grind on #5 (#1 is reasonable for espress, #5 is our cupping setting, and slightly finer than pourover). Not only is it important to always use the same setting, but I recommend having a small grinder with low retention dedicated to color readings. We use a Fellow Ode for our color measurements, and we never use the grinder for any other purpose. We do this because we want the burrs to dull as slowly as possible. If you use your cafe grinder for color readings, the color readings can easily drift 5–6 points within a year as the burrs get duller. I expect our Fellow Ode to offer consistent color results for the next 20 years at our current rate of use.

I recommend using a relatively fine grind and tamping the ground sample if possible. A coarser grind may cause larger chaff particles to float on top of the ground sample, making the result lighter. Tamping helps to create a smooth surface, which improves measurement accuracy.

Timing of color readings

I can’t say if there is a “best” amount of time between roasting and taking a color measurement, but for the sake of rapid feedback and workflow, we take color readings of every batch as soon as the beans leave the cooling tray. We want to know the weight loss and color of the previous batch before we reach first crack in the current batch while roasting, in case we need to make a change to our roast color.

Quaker sorting

Whether you sort quakers or not, it is important to standardize the proportion of quakers when measuring color. Variability in the number of quakers can impact color readings, since quakers tend to be much lighter in color than mature seeds. At Prodigal, Mark and I hand sort to an agreed-upon level that mimics the degree of sorting we expect our optical sorter will do for each coffee. That is not as difficult as it may sound, as we hand sort samples for cupping, and frequently communicate about, and compare, our perceptions about how much sorting we will do for each coffee.

Whole-bean color readings

I consider ground-coffee color readings more important than whole-bean readings, but we always measure both whole-bean and ground color. This is not only to take yet another measurement of our roasting consistency, but also to learn how to manipulate the spread between outer and inner roast color.

Whole-bean readings tend to be a little less reliable than ground readings. This is due to several factors, including the bean surfaces being rounded, variability in the number of beans oriented with their “cracks” facing the color meter lens, and variation in the amount of silverskin stuck to the outside of beans. Much like with ground-color measurement, if we are surprised by a reading, we will repeat it a few times.Calibration

I don’t have enough experience with various color meters to say how often or why they go out of calibration. My recommendation is to recalibrate the color meter before each roast session, and to liberally recalibrate if multiple readings are out of the expected range.

Weight Loss

It is essential to precisely measure the weight loss of every batch. Not only is weight loss a great proxy for overall roast development, but weight loss readings complement color readings well. If, for example, our roasted weight loss for several batches of a given coffee is 11.0, 11.0, 11.0, 11.0, but the ground-color readings are 98, 100, 102, 104, there is almost certainly an error in the color measurements. This pattern may indicate that the quaker sorting was not consistent or that the color reader needs calibration. Likewise, if the color readings are 98, 99, 98, 99, but the weight losses are 11.0, 11.0, 11.9, 11.1, the third weight-loss reading is suspect. The problem may have been user error, something was touching the scale to influence the reading, or perhaps some beans were lost in the roasting process (this happened to me recently while sample roasting; I set the airflow too high, and sucked a few beans out of the roasting chamber and into the chaff drawer. I was confused by the weight-loss readings until I opened the chaff drawer and realized the problem. I consider taking both weight loss and color readings a form of checks and balances in roasting QC.

Difluid Omni and sample tray / Omni app data presentation of whole bean color / alternative data presentation for ground coffee color

24 October 2024, 10:03 pm - Introducing the Ceado Hoop

Like many of you, I’ve seen the Ceado Hoop here and there, and never paid much attention to it. But when my friend Alessandro of Aroma Cofffee in Bologna brewed a Hoop of a Prodigal coffee for me this summer, I was intrigued, and only then realized the genius of the Hoop’s design.

After tasting the coffee Alessandro made, I reached out to my friend Cosimo Lombardo who now works with Ceado. Cosimo and I had a wonderful conversation about the Hoop as well as some of Ceado’s other projects (more on that in the future.) I immediately signed up to sell The Hoop due to its impressive combination of quality and simplicity.

How to brew using The Hoop

To brew coffee, the barista pours water slowly into the outer chamber of the Hoop, and the Hoop does the rest. The brewing chamber is “no bypass” (hat tip Jonathan Gagné) and the design ensures the slurry never rises too high. Both features decrease the potential for astringency.

The Hoop may be the perfect manual brewer for cafes, as baristas can simply pour and walk away, knowing that four minutes later, the Hoop will deliver an excellent extraction.

There is no need for a prewet, a bloom, or a spin or swirl. :0. Just pour slowly.

If the coffee blooms to form a thick crust, one may want to use a WDT tool (or fork, or whisk) to submerge the crust after pouring. Very fresh or dark roasts will likely require WWDT (wet Weiss Distribution Technique) to break and submerge the crust.

The Hoop has every attribute of a great manual dripper:

Requires no skill

Takes scant barista time (this is especially valuable to cafes)

Offers low risk of astringency

Makes even extractions easy to produce

Offers near-perfect consistency

Just pour the water in the outer ring and four minutes later, enjoy some incredible filter coffee.

Deep bed, shallow slurry

Like the Pulsar, Tricolate, and Filter3, The Hoop is a no-bypass brewer, which means astringency is easy to avoid, and The Hoop produces high extractions using a relatively coarse grind. The small-diameter brewing chamber provides a deeper bed than most no-bypass brewers. Only Filter3 has a deeper bed.

The genius of The Hoop lies in allowing the barista to pour all of the water at once, while limiting the rate water enters the brewing chamber.

Three brewing dynamics help limit astringency:

sufficient bed depth

maintaining a shallow slurry

introducing water to the brewing chamber in such a way that it does not damage the integrity of the coffee bed

Sufficient bed depth is important because coffee beds act as filters that clarify brews. Deeper beds are better filters, and mitigate astringency. In a deeper bed, a smaller percentage of channels reach the bottom of the bed, limiting the amount of astringent particles channels deliver to a brew. A shallow slurry decreases astringency by limiting the (water-column) pressure on the coffee bed. The more pressure exerted on a coffee bed through suction or pressure, the more it will exploit a given channel.

Optional upgraded filters

Each Hoop comes with a pack of 100 standard filters from Ceado. The standard filters require a coarse grind to achieve the recommended 4:00 brew time. I offer optional upgraded filters as an add-on for those who want to use a finer grind to achieve higher extractions with excellent flavor clarity in the same 4:00 brew time.

The upgraded filters, as well as my personal “how to” guide to the Hoop, are available only through www.scottrao.com

CLICK HERE TO TRYTHE CEADO HOOP

15 September 2024, 3:06 pm

15 September 2024, 3:06 pm - Pros and cons of various roast-control systems

There are currently a few ways to control roasts; from most common to least common are:

gas valve % (power settings)

inlet temperature

exhaust (environmental) temperature

PID curve management

GAS % (POWER PROFILE)

Most roasters operate by gas % or “power profiles”. This includes most popular versions of Probats, Diedrichs, Giesens, and Lorings, etc. used in specialty coffee. While using gas valve or power settings is intuitively easy, every experienced roaster has learned the hard way this system does not guarantee consistency. For example, you may find batches early in a roast session run slower than batches later in a session, or batches run faster when the ambient environment in the roastery is hotter. In the former case, the roaster needs a more effective between-batch protocol. In the latter case, the roaster must either control the ambient conditions (difficult or expensive), or alter the gas/power settings depending on the ambient temperature (also difficult).

Above is an example of successful roast replication using gas-valve settings on a Giesen W6. The key to the consistency here is the BBP

INLET-TEMPERATURE CONTROL

Inlet temperature is the temperature of the air entering the roasting chamber. Machines that can control roasts based on IT include IMF, Roest, Sivetz, Brambati, and many larger, industrial machines. The great advantage of IT control is it can mostly or completely neutralize the influence of changing ambient conditions. For example, when using IT/BT recipes (inlet temperature control with changes in IT based on bean-temperature setpoints), both our IMF and Roest machines will trace curves accurately, always staying within one second of the reference curve, whether our roastery’s ambient temperature is 15°C (50°F) or 25°C (76°F), assuming the same green-coffee temperature in each case.

Here are five consecutive batches from yesterday's roasting session at Prodigal. A simple inlet-temperature recipe can yield impeccably consistent curves, roasting statistics, and cupping results.

EXHAUST-TEMPERATURE CONTROL

Managing roasts based on exhaust or environmental temperature is conceptually backwards. It is akin to driving by looking in the rear window of the car; it may work sometimes, but I wouldn’t trust it. This control system has been the standard on the Ikawa for a long time, it is an option on the Roest (that fewer and fewer people use), and it has been used in some third-party roast-automation software.

PID CURVE MANAGEMENT

PID Curve Management has potential, but no one has fully realized that potential yet. Kaffelogic and Loring’s “profile roasting” automation use PID curve management, and Artisan software can manage curves using a PID. The idea is the software will make countless small adjustments to the power settings in an attempt to replicate a reference bean-temperature or ROR curve.

PID control has a few challenges. For one, if a roast falls behind the reference-curve target, it is critical that the machine has ample “extra” power to quickly get back on track. In the case of the Loring automation, for example, if you see the machine stuck at either the lowest or highest power setting for more than a few seconds, it means the machine is struggling to match the reference curve. A second challenge is that the optimal PID settings change throughout a roast: ideally, one would want a very “aggressive” PID during the first minute or so of a roast, when temperature changes are rapid and dynamic, and a “mellower” PID mid-roast, before again needing an aggressive PID to manage the rapid changes in temperature and moisture release during and after first crack. A third challenge is how to deal with the (fake) declining BT readings at the start of a roast, since the BT reading is not accurate until after the turning point. There is no easy answer to how to program an automated PID system to manage a curve while the BT data is both inaccurate and also changing rapidly.

Here is an example from Loring's profile automation... note that the machine does not attempt to manage the curve until after the turning point. After the turn, the machine switches between full power and minimum power, as the machine can neither lower the power enough or raise it enough to track the reference curve.

2 September 2024, 11:25 pm - Viva Colombia

I recently spent twelve days in Colombia. It was an unforgettable trip, full of learning, beautiful scenery, wonderful hospitality and new friends. I’d like to share a bit of my experience with you.

I visited Colombia at the urging of Diego Bermudez. Diego and became friends after having dinner together in San Francisco and Chicago, and we plan to work together on some future projects. After his numerous invitations to come to Colombia, I found time in May. Since I was visiting Colombia, I made plans to meet several farmers, mills, and exporters we work with at Prodigal.

Medellin

My first stop was Medellin, a dramatic, mountainous city of five million people. While in Medellin, I had the pleasure of visiting Nikolai and Manuela at their apartment and their mill/lab/roastery located on a coffee farm on the city fringe. After a delicious vegan breakfast, we visited the mill and lab, which are a five-minute walk from their apartment. Nikolai mills coffee in Medellin for several of Colombia’s best producers, including the famous Wilder Lazo. Nikolai and I had several cupping sessions, worked on sample-roast profiles on his Roest, and talked about ways to hack his Diedrich IR-12. We toured their small mill as well as the farm’s nursery. Nikolai’s operation is small, but laser focused on top-quality coffees.

On day two I visited Stephen at The Coffee Quest mill near the Medellin airport. The mill is fantastically clean and efficient. We cupped two dozen coffees, talked about their QC protocols, sample roasting, buying stations, and their systems for labelling and tracking coffees through the milling process. If you’ve tasted Prodigal’s Perlitas, Pradera, Finca Costa Rica, or Las Jazmines, they came from Coffee Quest. If I had to sum up Coffee Quest in a few words, they would be: efficient, systematic, and excellent value.

Cauca

On day three, I flew to the small airport at Cali to meet Diego and Matheus. Our first stop was Finca Betel, to meet Diego’s cousin César and his family. Mark and I already loved César for his exceptional coffees, his infinite friendliness, and his sunny outlook on life, so I was eager to meet César in person. Upon arrival at the farm, we were greeted by César, his friends, and his parents. I was urged to sit, and a plate of food immediately appeared. We spent hours in rapt conversation about life and coffee, we shared several cups of César’s clean, delicate, lactic-fermented natural Laurina, toured the farm and processing areas, and cupped several coffees. I felt like part of the family. The scenery at Betel is gorgeous: the farm is perched on a hillside overlooking Calima Lake. The covered, open-air living room of the house fostered vibrant conversation with expansive views. César has often told me he lives in paradise, and I agree.

After dinner, Matheus informed me we would spend the night at Betel. I was a little concerned, because Diego and Matheus had told me several times that protestors and guerrilla activity in Cauca often shut down all of the area roads. Given that the roads were currently open, it seemed prudent to drive to Diego’s farm that day. Sure enough, we woke up at Betel to the news that there were several protests and road closures in the area, we couldn’t go to Finca El Paraiso, and Diego could not go home. The protests grew quite extensive, so later that day we abandoned our plans to visit Paraiso. Our consolation prize was a blissful day at Betel, more touring, learning, and wonderful conversation, and finally a visit to the cafe César and Diego co-own in the town of Florida. The cafe was gorgeous, with a Stronghold roaster and a modern third-wave coffee bar, as well as waffles made from the local favorite “pan de bono,” which, happily, is gluten free. I had my first waffle in 20 years before heading to the airport to return to Medellin.

Clockwise: César with our coffees; Diego making our morning coffee; me with Matheus, Diego; cupping with legends; César explaining his drying oven; the view from above Finca Betel.

Medellin

I returned to Medellin for a few days and had some relaxed visits with Nikolai and Stephen as well as some new Colombian friends. I was disappointed to miss Finca El Paraiso, but enjoyed having a couple of free days in Medellin.

San Agustin

Next I flew to Pitalito with a stopover in Bogota, with a plan to meet Andrew and Wilson from Suited NYC in Pitalito. They would join me for the second half of the trip. Bogota airport was a little confusing, as it wasn’t clear which terminal I needed to fly from, or even which airline to check in with, as my flight was with Clic Air, a subsidiary of Avianca. The confusion cost me some time, and I decided to take a taxi between the terminals to save a few minutes. While in the taxi, I saw Andrew and Wilson on the sidewalk, also seemingly confused about where to go. I asked the taxi to stop, I yelled their names, and they hopped in the cab. I took the chance meeting as a sign of good fortune.

<< caption: Andrew and Wilson at Masaya

When we arrived in Pitalito, we were met by Adriana, co-founder of Inconexus. We stopped at an Argentinian steakhouse for lunch, and some musicians dropped in to play during the meal. After lunch we drove two hours down a dirt road to Finca Las Palmas, a gorgeous farm owned by Efren and Adriana Mora, that Prodigal purchased from in 2023. While rain poured down, we were treated to a tour of the drying patios, guardiola, and the farm’s coffee bar, where Efren roasted and brewed us a cup of his alcoholic-fermentation natural. We were blown away by the quality of green, the roasting, and the brewing, and i got a kick out of watching Andrew drink the coffee, his first in Colombia. I could tell he was wondering “does everyone in Colombia roast coffee so well?” Unfortunately not, but I experienced several impressive, delicate roasts at Las Palmas, Betel, and Nikolai’s lab. Most producers and exporters roast rather dark by modern standards, but it was encouraging to find so many people in Colombia roasting light.

The skies cleared as soon as we were ready to tour the farm, as it did every time we needed to go outside. I won’t say we influenced the weather, but a sort of Gabriel-Garcia Marquez magical realism followed us everywhere, whether it was perfectly-timed weather, our sense of time expanding and contracting, or just feeling like we were in a fantasyland. At Las Palmas we tasted our first grenadilla, my new favorite fruit, and guama, a giant pod with seeds encased in a pulp reminiscent of cotton candy. Personally, I loved that so many Colombian fruits had unexpected textures and very mild sweetness. Before we left, I gifted Efren a NextLevel Pulsar, we brewed one together, and we had yet more delicious coffee, alongside some unforgettable arepas fresh from the oven.

From Las Palmas we drove to Masaya, a fabulous accommodation perched on the edge of a canyon in San Agustin. Our hunger made dinner all the more special, and we spent the meal pestering Adriana with questions about Inconexus’ mission and work with farmers, and about coffee trading in Colombia. Bizarrely, the same musicians from lunch in Pitalito showed up to play at Masaya in San Agustin.

The next day, Adriana took us to five coffee farms she works with, beginning at Llanada, where Oscar Omer, a chemist who formerly worked in the yogurt industry, gave us a tour and graciously fielded my many questions about microbes and coffee fermentation. From Llanada we visited El Placer, owned by Pastor Odoñez, and Finca Filadelfia, owned by Ciceron and Alicia Rodriguez, who graciously served us lunch. Prodigal recently purchased some coffee from Filadelfia, and having met the wonderful people behind the coffee makes it even more special to offer it to our customers.

Adriana did a great job of showing us several farms that produced lovely coffee using different approaches. Some farmers were more scientific in their approach to fermentation and drying, others followed more traditional systems, and all proudly showed us their gorgeous farms and shared their life’s work. At the end of our day of farm tours, we stopped at the Inconexus warehouse in San Agustin. We were treated to some nicely roasted coffee (again!), a tour of their operations, and a cupping of about 15 coffees. The cupping generated some lively discussion about sample roasting, scoring, processing, and things we had seen that day. The Inconexus team was gracious and friendly, and I felt great about being their customer.

Clockwise: Enjoying the Finca Las Palmas family; drying patio; guardiola; enjoying a cup at Las Palmas, Pastor Odoñez and Adriana on Pastor’s rooftop drying patio; Adriana sniffing a fermentation barrel at Las Palmas;

San Adolfo

The next morning we said our goodbyes to Adriana and drove to San Adolfo to meet Nikolai and his photographer friend Carlos. After dropping our bags at a (coffee) farmstay owned by Victor, one of the most inspiring, friendly young people I’ve ever met, we drove to Wilder Lazo’s farms. After some hellos, we immediately jumped into the first of several cuppings in his lab. We spent the next two days touring Wilder’s farms, cupping every chance we could get, and discussing sample roasting, color measurement, and approaches to processing. We tasted some lovely coffees, including the uber-light Prodigal roast of his Lot 2 Geisha I had put on the cupping table. The most rewarding moment of the visit was when Wilder praised my roast of his coffee and asked how he could get that kind of flavor from his sample roaster.

Pitalito

We spent one night in Pitalito after leaving San Adolfo. Wilder and his wife Leidy joined us in Pitalito for a lovely sushi dinner, nonstop vibrant conversation, and the next day we cupped at the office of an exporter friend of Nikolai’s. While Pitalito is a modest city, what’s fascinating about it is the amount of coffee traded there. Pitalito is a hub where coffee farmers sell their harvests to middlemen, and it seemed half of the buildings in Pitalito were warehouses for green coffee in various states (cherry, parchment, green).

Such scenes led to many conversations with Andrew and Wilson about the realities of coffee trading, and how they contrast with the online and marketing myths about how coffee gets from farmers to consumers. Marketing materials and politicized online discussions about coffee production rely on over-simplified narratives. The reality is complicated, heterogeneous, and messy. Many blog posts on the subject will follow, I’m sure. Spoiler alert: choosing relatively pricey, specialty coffee is the only sustainable path for the industry.

Bogota

From Pitalito, Nikolai, Carlos, Andrew, Wilson, and I flew to Bogota for dinner al fresco at a delicious Italian restaurant. While I like rice, beans, and plantains as much as the next person, I welcomed a meal of salad and fish. The dinner conversation about what we had experienced and how the trip shaped our perspectives on coffee production was as vibrant as ever, and I’m grateful to have had their companionship on the trip. That night we all went our separate ways, with an unspoken acknowledgement that we had all just experienced something special together.

Takeaways

There is too much I want to say about the ways the trip to Colombia impacted me. The generosity, hospitality, and respect we received were humbling and heartwarming. Everywhere I went, I felt like family, and felt connected to people in a way that is often challenging to feel with new acquaintances in the US. Warmth, friendliness, conversation, a slower pace of life, and a shared love of coffee obliterated concerns for material wealth or modern conveniences. It’s impossible to care much about “first world problems” when sitting in the outdoor living room of wonderful new friends and drinking fabulous coffee produced in that place, by those lovely people, overlooking impossibly beautiful scenery.

Andrew and I often remarked to each other how the farmers we met seemed happy, healthy, and immensely satisfied with their lives and work. While there are indeed very poor people farming coffee in difficult circumstances around the world, there are also farmers who love their lives and their work, are experts at their craft, have wonderful, deep connections to family, community, and the land, and live in some of the most beautiful places in the world.

If, as Arthur Brooks posits, happiness derives from the three pillars of enjoyment, satisfaction, and meaning, then many of the people we met in Colombia have mastered Arthur’s formula. The enjoyment of shared experiences with tight family and community bonds, the satisfaction that can only come from hard work, and the sense of purpose and meaning farmers derive from their work with coffee, usually on land passed down several generations of their families, added up to a degree of happiness I don’t often see in richer, more modern countries.

Over the years, several friends who buy green coffee for a living have told me Colombia is their favorite country. I completely understand why.

26 June 2024, 12:17 am - The Bias Against Blends

The names “holiday blend” and “house blend” don’t exactly get the pulses of third-wave consumers racing. Blending has tremendous potential to mold or improve coffee flavor, but has an unfortunate reputation among many coffee lovers.

Compared to “single origin” offerings, most blends are made up of cheaper, darker roasts meant to be “accessible” and paired milk and sugar. None of this is a commentary on what one should like; to each his or her own. I’m sure some stellar light, interesting “house blends” exist.

“Everything is a blend”

At the farm level, cherry from various types of coffee trees may be blended and harvested together. At the dry mill, coffee in parchment or seed form, from numerous varieties or farms, may be blended at various steps to produce a lot with a single marketing name. A roaster may blend several coffees before or after roasting. A barista may combine multiple coffees to make a filter coffee or espresso. In a sense, almost everything is a blend, even coffees called “single origin.”

The purposes of blending

Blending at the roastery level can serve many purposes. Roasters may blend coffees to maintain a certain flavor profile year-round, to try to “hide” an aging or otherwise disappointing lot of green coffee, or to attempt to save money while achieving a consistent flavor profile. Paradoxically, blending may be the easiest and most impactful way to improve coffee flavor after roasting.

Blending can achieve an under-appreciated flavor synergy. One of the simplest ways to experience this is to blend a small amount of an intense, fruity natural coffee with a large amount of subtler washed coffee with lower-intensity fruit. While the natural coffee on its own may be too fruity or intense for some, it can spike the fruitiness of the blend just enough to create a “best of both worlds” effect. Blending can convert a “bug” into a “feature” by toning down its intensity. A roaster or barista may create almost any desired flavor profile through blending, but would likely struggle to achieve such flavor range if limited to using only one “single origin” coffee.

Not many roasters or baristas bother to blend expensive, high-scoring coffees. After all, those coffees tend to be beautiful as is. But blending can sometimes improve even those coffees. At the end of our daily cuppings at Prodigal, Mark and I often spoon various proportions of coffee from different cupping bowls to create impromptu blends. More often than not, we prefer some of the blends to any of the individual components. The rare exception is when we have a nearly flawless, balanced coffee that is so much better than any other coffee on the table that it is nearly impossible to improve that special coffee.

Pre-blend or post-blend?

I recommend post-roast blending over pre-roast blending. The problem with blending before roasting is that beans of differing sizes and processes will develop at different rates. Pre-blending often makes ROR curves easier to manage, but may result in some beans being underdeveloped or a little too dark while other beans are developed beautifully. Pre-blending is generally not a good idea except when blending coffees of similar size and processing type. There is some folklore in Italy that says if you blend the green coffee for a few days before roasting a pre-blend, the beans’ moisture contents will homogenize, making them roast more harmoniously. I cannot verify if such moisture migration occurs, but would still avoid pre-blending due to variations among blend components’ bean sizes and processes.

Roasting before blending allows a roaster to optimize the development of each blend component. Post-roast blending also allows the roaster or cupper to adjust blend ratios to optimize the roast batches on hand, which can be more effective than blending by formula if not all batches are on target.

“Solubility matching,” the idea that one should blend only coffees of similar solubility, was once all the rage. The idea was that if (for example) a 50/50 blend consisted of, say, one coffee that would extract to 24% and another at 20% (using a given set of brewing parameters), each component would extract at a compromised, suboptimal level. However, this idea was never fully valid; the end result in the cup is an approximation of how the coffees would taste if brewed separately and then combined. Likewise, when blending two coffees that produce different particle size distributions (PSDs), the blend’s (PSD) will be the weighted average of each component’s PSD.

How to Blend

There are no rules to blending, but I will offer a few recommendations:

☞Choose post-roast blending over pre-blending. Post-roast blending offers more control and makes it easier to optimize the roast of each blend component.

☞Use the spoon method: the best hack for deciding which coffees to blend, and in what ratios, is the spoon method:

Set up a cupping bowl of each blend component candidate

Label the bottom of several empty cupping bowls with various blend ratios (such as 1:1, 2:1, etc)

When the coffees are cool, spoon various ratios of coffee from each bowl into an empty cup. For example, if you take three spoonfuls from cup A, two from cup B, and one from cup C, that would represent a 3:2:1 blend of those coffees.

Make several such blends and have someone else shuffle the order of the cups

Taste the cups blindly to decide the optimal blend

☞Take chances. Try blends that don’t make sense or seem like they won’t work, and take the opportunity to think outside the box and learn about how coffees interact.

☞Avoid blends in which one component makes up less than 15% of the blend. Even with adequate mixing, the ratio of blend components in each small dose of coffee is likely to vary. For example, in the 3:2:1 blend above, component C is 16% of the blend. If you brew using 20g doses of the blend, C may make up 10% of some doses and 20% of other doses. If a blend component were to make up only 10% of the total blend, some doses would have just a few percent of that component, making that component’s contribution to flavor almost invisible.

3 June 2024, 5:10 pm

3 June 2024, 5:10 pm - How the Decent evolved to make delicious espresso easier

Disclaimer: I’ve worked with Decent Espresso from the start, helping to plan and design the DE1. I may be biased, but everything in this post is factual.

Having a software background, John designed the DE1 to be “unfinished” and able to add new capabilities as we think of them. John expected researchers and coffee nerds to come up with “what if it did this?” ideas, and he wanted the machine to evolve with that discussion. If you buy a traditional espresso machine now, its capabilities will be identical in ten years. If you buy a DE1, its capabilities change and improve almost weekly.

Decent Espresso users have access to the Decent Diaspora, a private online forum. The forum is always friendly and civil, and the number of incredibly intelligent people there is impressive. The community has come up with countless new ideas about espresso and has helped improve the DE1 and our understanding of how to make great espresso. Many of the espresso innovations I mention in this post would not have been possible without the Diaspora brain trust.

In the early days, the DE1 was considered “unforgiving” by many. I didn’t mind, as the DE1’s ability to control shot parameters more than made up for its early challenges.

The DE1 brewing Filter3

I think the machine was considered unforgiving for a few reasons:

Most of our profiles used a slow preinfusion flow rate, whereas everyone else, except Slayer users, was using a faster fill.

The Decent’s graphs allowed us to see evidence of extraction problems we had not been able to see before.

High quality, budget grinders were rare at the time. The Niche Zero and other new grinders changed that, and helped make it easier to pull good shots.

Since that time, we’ve learned a lot about shower screens, water distribution, and headspace above the puck, and have redesigned several parts to take advantage of what we’ve learned. Our forthcoming shower screen is incredible for both espresso and filter3. Over the past nine years the hardware has become much quieter, gained steam pressure, and become easier to control without the tablet, via the grouphead controller. The hardware improvements are impressive, but frequent software upgrades are what has set the DE1 apart from any other machine.

During the first year I had a DE1, I created the allongé and blooming espresso profiles to improve the quality of espresso from light roasts. Allongé taught us that lighter roasts taste better with faster flow rates, and has produced some of the most fruit-forward coffee I’ve ever tasted. Blooming taught us that the extraction “ceiling” is indeed above 30% EY, and that extremely high extractions can produce beautiful flavors with the right coffees. I haven’t uttered the phrase “overextraction” since creating the blooming espresso; it proved that harsh flavors do not in fact come from high extraction levels, but from channels. Jonathan Gagné has hypothesized that channels yield astringency and bitterness not because of high extractions along channels, but because channels allow larger, astringent particles an easier path out of the coffee bed and into the cup.

Allongé and Blooming, while quite different, share something in common: they both make espresso from light roasts less sour and bitter, and more balanced. A traditional espresso extraction removess more material from the upper layers of the puck, and at higher temperatures, than from the bottom of the puck. Allongé increases extraction and temperature at the bottom of the puck by running a large volume of water through the puck. Blooming increases extraction and temperature at the bottom of the puck via a 30-second bloom that homogenizes temperatures and extraction throughout the puck. Blooming arguably offers a more even espresso extraction than any other profile or machine can.

We learned that the most effective preinfusion may include a shift from high flow to low flow with a modest pressure buildup. We have found a slow pressure ramp after preinfusion, similar to that of some manual levers, helps compensate for imperfect puck prep. Jonathan Gagné came up with an “adaptive” profile that holds flow rate at whatever it was at a shot’s pressure peak. In the case of a grind setting being poorly “dialed in”, the adaptive profile optimizes the flow rate for the current grind setting.

The Decent community has come up with various ‘failsafe” ideas that prevent bad shots. For example, if the grind is too fine, rather than a shot choking and being destined for the sink, one can program the DE1 to limit the pressure and maintain a reasonable flow rate. Flow profiles have some ability to “heal” channels by decreasing pump pressure when the machine senses an increase in flow rate.

More recently, I have turned the DE1 into the world’s best single-cup filter-coffee machine. The Filter3 basket offers a “no bypass” brew with control over flow and temperature, and is one of the few single-cup brewers that offers appropriate bed depth with a 20g dose. Anyone who tasted Filter3 from the Prodigal booth at SCA Expo can vouch for its excellent, hands-free extraction quality.

Later this year, Decent will release its beautiful new machine, the Bengle, with some impressive new features, as well as a clever new shower screen that improves water distribution and prevents water from merging into a small number of streams.

Stay tuned, things are always evolving and improving.

The Decent Bengle, coming soon

23 May 2024, 9:10 pm - Prodigal QC Protocols

I’d like to share a brief overview of the quality-control protocols we use at Prodigal. I think you’ll find them interesting, and probably a little extreme. We take great pains to buy and roast the most delicious coffee we can, and admittedly, some of these efforts make us less, not more, profitable. Hopefully that will change with time if the market comes to value things like quaker sorting and buying from a roaster able to replicate flavor batch after batch.

Note: I have not been paid, and will not be paid, by manufactureres of any of these equipment I mention in this post.

Some of our most costly QC protocols include:

We go to great pains to purchase almost exclusively coffees processed within the past month. The limitations and costs associated with choosing only recently processed coffees, and getting them to Prodigal in a matter of days or weeks, and not months, are extreme.

We remove quakers to improve cup quality, but is painfully expensive. So far, the market hasn’t rewarded that effort, but we sleep better at night knowing that we have a lower percentage of quakers in our bags than any other roaster. Some of the tedious “knee-jerk moral outrage” crowd online is “offended” by our intense quaker sorting. Any consumer reading that nonsense will think “I guess those roasters sell coffee with a lot of quakers,” so I welcome their complaining. We wouldn’t be a target if we weren’t doing something special. We want to raise the bar in every way we can.

For a given coffee we have a ground-coffee color-range tolerance of four points, an accepted weight-loss range of +/-0.2%, and a cup-score floor of 87.5 points. Any batch that doesn’t meet those standards goes in our heavily discounted “first batch” offering. Selling First Batch kills our margins, but it allows us to sleep well at night, and it absolutely thrills customers who can’t quite afford to pay full retail for lovely coffee. There are times when we spend a small fortune on green coffee and the arrival coffee is below 87.5 points. That can be very costly, as we have to find a way to sell that green rather than roast it and put it in a Prodigal bag.

Green Buying

Green buying is the most challenging and time-consuming part of running our roastery. We roast dozens of samples each week, often repeating a sample roast if the first attempt did not land in our desired ranges for ground color and weight loss.

We measure the moisture content of each green sample before roasting, using the Agratronix Coffee Tester. It’s probably not the most accurate moisture meter on the market (it seems to read a bit high), but it’s consistent enough to be reliable and useful. We roast samples in the Roest L100 Plus. (Disclaimer: I have a small financial interest in Roest.) Immediately after roasting, we calculate weight loss, and measure color using the DiFluid Omni. The Omni is consistent and wastes only 3—5 grams of coffee per ground-color reading. We are currently testing a beta version of the DiFluid Omix, which has exciting potential as an all-in-one color/moisture/density/screen size/water activity meter. We have yet to test its accuracy against other devices. If the weight loss or color of a sample is not within our target range, we will immediately re-roast that coffee. We save weight loss and color data in the Roest software.

The next morning we cup our sample roasts blindly, often with production roasts and samples from other roasters on the table. We remove quakers from each cupping bowl and for any coffee we record the percentage of quakers by weight of any coffee we are considering for purchase.

We carefully manage our water chemistry and weigh both the water and beans in the cupping bowls. We break the crust at 4:00 and begin slurping at around 13:00. We take copious notes on each coffee and score them before discussing our findings. We debate the merits of various cups. After this we reveal the coffees, take notes, and discuss further. We cup an average of 125 bowls every week.

We will often re-cup a coffee if we missed a substantial quaker and tasted its influence in a cup. We re-cup any coffees we consider potential buys, if we scored the coffee 87.5 or higher, or we think the coffee may have 87.5+ potential if we change something in our processes. We will often brew potential purchases as Filter3 to get a different impression of its flavor.

We pass on some coffees that are 87.5. Reasons for passing can include price, funky flavors, various types of risks, and marketability. We’re not price sensitive, but we don’t accept when a supplier asks for double the price of better alternatives. While better coffees tend to cost more overall, some fantastic green is a relative bargain, and some mediocre green costs double or triple what better alternatives do. A few middlemen buy green, mark up the price fabulously, and wait to see who bites. We’ve seen a few lots offered by various middlemen at wildly different prices. Cost of production, politics, logistics hurdles, and government policies all contribute to what sometimes seems like irrational pricing. The quaint notion many people have of a farmer asking X price, and then shipping coffee directly to a roaster exists; we have and love those relationships, but they are not the norm, especially not with certain origins or larger-production lots. We try to have as many such direct relationships as we can, but the laws and logistics in some countries make such simple, direct, transparent transactions challenging or impossible. Thankfully, technology is bringing farmers and roasters closer together in many ways, and we love being able to wire money directly to farmers when possible.

Risk ManagementNot a day goes by that we don’t discuss risk at the roastery. Risk can take many forms, and without good risk management, I don’t think any producer, middleman, or roastery can survive. One risk we learned about the hard way last year was the risk that sample material had been prepared to a much higher standard than the arrival coffee. This is a common practice that somehow never favors the roaster, and undermines trust, which ultimately holds down prices and inhibits productive relationships. Anything that promotes transparency, security, and trust paves the way for potentially higher prices, in any industry. Think about this: every rich country in the world is what economists call “high trust” and every poor country is “low trust.” There may be some chicken and egg in the dynamic, but no one can argue against honest, open practices that promote trust.

There are many other sources of risk to a roastery: will a coffee degrade during transit? Will coffee take far longer than expected to arrive? Will a roaster purchase too much green and watch it age, not knowing how to sell it? Will a key account go to a competitor, causing a roaster to get stuck with extra, expensive, unsellable, aging inventory and negative cash flow? Will a coffee fade prematurely or taste baggy soon? Will a coffee simply not sound appealing to customers? Will a roastery run out of cash because it has too much money tied up in green inventory and contracts? I am not in any way downplaying the risks farmer face; those are massive and almost unthinkable. But that doesn’t change the fact that many roasters and green importers have gone out of business due to being long on expensive green or receiving low-quality, unsellable green.

We have had coffees arrive with so many quakers that we had to sort 40% of the material in order for the coffee to meet our quality standards. (The samples were somehow almost completely free of quakers.) Obviously, that was not a profitable purchase. We have had coffees we could not sell because they arrived with fade. One coffee was beloved among customers, but we began noticing fade in about 1 of 5 cups, so we reluctantly yanked it from the menu.

In 2023, we purchased five dud coffees. None of those coffees reached our menu. Since our business model calls for an extremely high standard for green coffee, when green coffee arrives below our standard, we need to sell it to someone else. Thankfully, we’ve always found a new home for green coffee we didn’t want to keep.We store our green in airtight bags in a refrigerated and humidified room. We monitor green for changes in moisture content over the weeks we store the coffee. We store a very small amount of exceptional green in vacuum-sealed bags in a freezer. Cold storage temperatures retard aging and decrease a major source of risk at a roastery.

We buy relatively modest amounts of each coffee we purchase. Not a day goes by that I don’t have Ryan Brown in my head, telling me it is better to buy too little green than too much.

As Ryan wrote in Dear Coffee Buyer: “It takes mere days to buy a quality coffee when necessary (call your importer, ask for samples, cup them, approve the best—or the least-awful—and ship it to your roastery), but it can take up to a dozen months to roast it all. Because of this, it is much easier to correct an underbought situation than to correct an overbought situation.”

I may have taken Ryan’s admonition to an extreme, but I’d rather run out of coffee at Prodigal than ever sell something that tastes a little aged.

So far, we have purchased very few coffees based on preship samples (PSS) or contracts for future harvests. At some point as we grow, we will have to increase our time horizon and risk tolerance. Our tiny size has allowed us to avoid that until now. New businesses are inherently risky; we were bound to make many errors in our first year, and we did. We bought bags that needed replacing. We bought an unusable optical sorter. We ran out of money a couple of times. We bought five dud coffees. We got screwed for $25,000 by a supplier who pulled a bait-and-switch with some green, and then spent five weeks avoiding our messages. Live and learn. Once we grow and feel more secure in our purchasing relationships, we’ll be able to shoulder more risk. Had we taken the amount of risk in year one that most roasters take in an average year, we would have had to change our business model or go out of business. Being a niche roaster without a retail cafe business or a large, not-so-picky wholesale account, we don’t have the usual outlets roasters use for their mistakes (cheap blends, iced coffee, etc).

No one says this out loud, but every roastery has a fair number of subpar green purchases each year, and they either sell the coffee as-is and hope customers don’t notice the low quality, or they hide it in a blend.

We are irrelevant in the market

For those who think it’s “wrong” to have high standards for green, remember: every quality roaster rejects more than 90% of the samples they cup. Unlike most companies, we do not buy green based on price. We prefer to pay high prices for extraordinary coffees. And there will always be a home for those 87-point coffees we reject; it’s not like we are the only possible buyer, or even an important buyer. Any supplier holding an 87-point coffee possesses something relatively easy to sell.

We take our responsibilities to our suppliers and our customers seriously. We pay perhaps the highest average green prices of any roaster in the world (>$10/lb FOB in 2023), we deliver it to customers who expect consistently flawless results, and we always offer a money-back guarantee.

We are small, and do not have a material impact on the market. Our best chance of having an impact is to spend lavishly on green, to put pressure on competitors to follow suit. A few times over the years (before Prodigal) I was accused on social media of influencing green prices. Such absurd accusations indicate many people don’t realize the size of the green market. Saying I can move green prices is like saying a single EV driver can influence petrol prices. If you were to make a list of the 1,000 people in the world who most influence green prices, I would not be on that list. If you think otherwise, please get out of your bubble and read some statistics about the $40,000,000,000 per year green-coffee market. (As an aside, about 10 years ago I visited an Italian roastery that almost no one outside of Italy has heard of. At that time, the roastery produced as much coffee per week as *all* US-based third-wave roasters combined. That roastery could have swallowed the combined production of Intelligentsia, Stumptown, Counter Culture, Blue Bottle, and Onyx without getting indigestion.)

From sample roasting to production roasting

While one cannot transfer settings or temperatures from a sample roaster to a production roaster, we use sample roasting to inform how to approach a new coffee in the IMF. We roast each arrival coffee 5—8 times in the Roest and cup those samples blindly to decide our production-roast targets for color and weight loss, and we note any unusual behavior a coffee displays in the sample roaster. We could not use this prediction system with most sample roasters, but the excellent control and data collection provided by the Roest make it possible.

Once we have chosen a profile and targets for our first production roast, we roast it in the IMF, with predictions for development time, roast duration, weight loss, and color. We rarely miss our targets by more than a trivial amount in our first production roast. After measuring color and weight loss of a roast, we may adjust our time targets and/or recipe in the IMF for subsequent batches. After our first batch of a coffee, we expect to be within +-0.1% of our weight loss target and +/-2 points of our color target on every subsequent batch. If we have any concerns, we brew a Filter3 or pour a cupping bowl of a batch right out of the roaster. Such rapid sampling isn’t ideal, but it is usually enough inform us of how to improve a coffee.

All batches that do not quite meet our standards get blended and sold as “First Batch.” If something were ever uncomfortably off-spec, we would sell it as grinder-seasoning beans. First Batch is frankly pretty good, and an incredible bargain.

Sorting

We run all roasted coffee through the MINI-125 optical sorter from Coffee Machines Sale.

We choose sorting weight loss by cupping several different sort levels. This process is time consuming and expensive, but our goal is to maximize cup score relative to cost by removing quakers. Quakers contribute astringency, vegetal, peanutty, and often stale flavors to coffee. They are difficult to avoid, and we do not want them in the coffee we sell.

Very few specialty roasters sort quakers, and none to my knowledge sort the percentage of quakers we do. We average 20% sort loss on most coffees, but have gone as high as 40% weight loss to ensure the result cups at 87.5 or higher in blind cuppings.

Quakers and odds and ends get bagged and sold as grinder-seasoning beans. We waste nothing.

Bagging

We bag coffee using a Dupre Simplex 1H3L weigh and fill. It’s fast and accurate to within one gram. We use a continuous band sealer, DS770, also from Dupre.

Production CuppingThe morning after production roasting, we cup every batch from the previous roast day. We skip cupping perfectly replicated batches. In other words, if three batches of a coffee all roasted in 8:31 with a weight loss of 11.1%, identical ground colors, and identical curves, we only cup one of the three batches. Our tolerances are such that almost all batches of a coffee are indistinguishable.

We save a sample of every production roast and attempt to re-cup the coffee after one, two, three, and four weeks, in order to taste the coffee as it rests and matures. We find our coffees taste best between 3–5 weeks off roast, which is why we sell several “rested’ offerings on our site. The rested coffees are popular, but really should be far more popular. We often get messages from customers who say “I finally waited four weeks to open a bag, and I wish I had been doing that all along.”

Thanks for reading.

8 May 2024, 12:34 am - Quakers and Optical Sorting

When we started Prodigal, I took a leap of faith on an optical sorter from Alibaba. I don’t think I have to tell you the rest of that story 🤕. After Mark spent months on Whatsapp with the manufacturer, only to realize the manufacturer didn’t really understand how to use the sorter for coffee, we gave up. The machine was simply too difficult to program.

Immediately after that, I had the fortune of running into Kacper from Coffee Machines Sale at World of Coffee in Athens. Kacper pulled me to the CMS booth, telling me I’d like what he was about to show me, and that he was going to give me an optical sorter. I was intrigued.

Kacper demonstrated an optical sorter with a machine-learning (AI, if you will) programming system. He passed a “too dark” sample of beans in front of the sensors, pressed a few buttons, and repeated the process with samples that were “just right” and “too light.” Let’s call it the Goldilocks program. The machine sorted the beans by color pretty well, and a few weeks later, Mark and I were the proud owners of a new optical sorter. Unlike the Alibaba seller, Kacper actually knew how to use the machine and coach us in its use.

I know several roasters who have purchased a very expensive, popular sorter, only to have a technician spend TWO TO FIVE DAYS at their roastery programming the sorter. Let’s face it, if an expert — who spends all of his time programming sorters — requires 2–5 days to program a machine, the customer has little chance of mastering such a machine anytime soon. Kacper set us up remotely in less than two hours on Facetime.

For those new to sorting, please understand that even with a good set of foundational recipes, the user still needs to be skilled at programming the sorter for new coffees. There is no such thing as “set it and forget it” recipes if you want the sorter to remove quakers with any precision.

Kacper told me “I know if you use this machine, you’ll love it. And if you use it and love it, others will buy it.” I told him I would promise nothing, because I can’t promote something I don’t believe in; my reputation is worth a lot more than a $14,000 machine.

Kacper was right, the machine is excellent, and he saved me from blowing $30,000 on a machine I would have found frustrating to use. I had no obligation to write this post, other than to pay a debt of gratitude to Kacper and CMS since the machine has been incredible for us. Paolo and I have since purchased a sorter (not free) for Regalia and Multimodal, and I’ve recommended the machine to several clients.

Let’s discuss some details about sorting, as I think it is both more complicated and more important than most roasters realize.

Sorting is not easy

As the examples of Alibaba and 2–5 day of initial programming show, sorting is not simple. The machine-learning system is by far the easiest I have seen. Programming a machine by showing it the actual beans to be sorted makes a heck of a lot more sense than trying to learn a complicated system of adjusting front and back cameras, red, green, and blue color settings, throughput speed, and an ultra-confusing bean-size setting I can not put into words.

What, exactly are we sorting?

In a word, filberts*, but you may know them as quakers. The historical industry standard for a quaker is the obvious, yellowish bean that at a glance stands out in bucket of roasted coffee. If you have never brewed a cup of pure quakers, please collect some, grind them into a cupping bowl, and add that bowl to a blind cupping. You’ll know when you get to that cup🤢. You will learn a lot in that first slurp. And, I’m sorry.

[*At Thanksgiving dinner last year, I was hand sorting quakers before brewing a pot of coffee. My friend Sharon asked me why I was removing those beans. I explained they were “quakers” and they tasted like peanuts. The next morning Sharon had forgotten the name of those beans, and when I served her coffee, she asked me if I had removed the “filberts.” 😜]

Those yellow quakers are awful. But what about all of those smoother and lighter-colored brown beans? Turns out those are quakers, too. Let’s call those pseudo-quakers for now, or filberts, if you wish.

Not sure if a bean is a pseudo-quaker? Take a potential quaker, smash it on the counter, and smell the crushed bean. If it smells like peanut, it’s a pseudo-quaker. If it smells like fruit and flowers, you just removed what was probably one of the best beans in the bucket. There is risk in over-sorting lighter-colored beans.

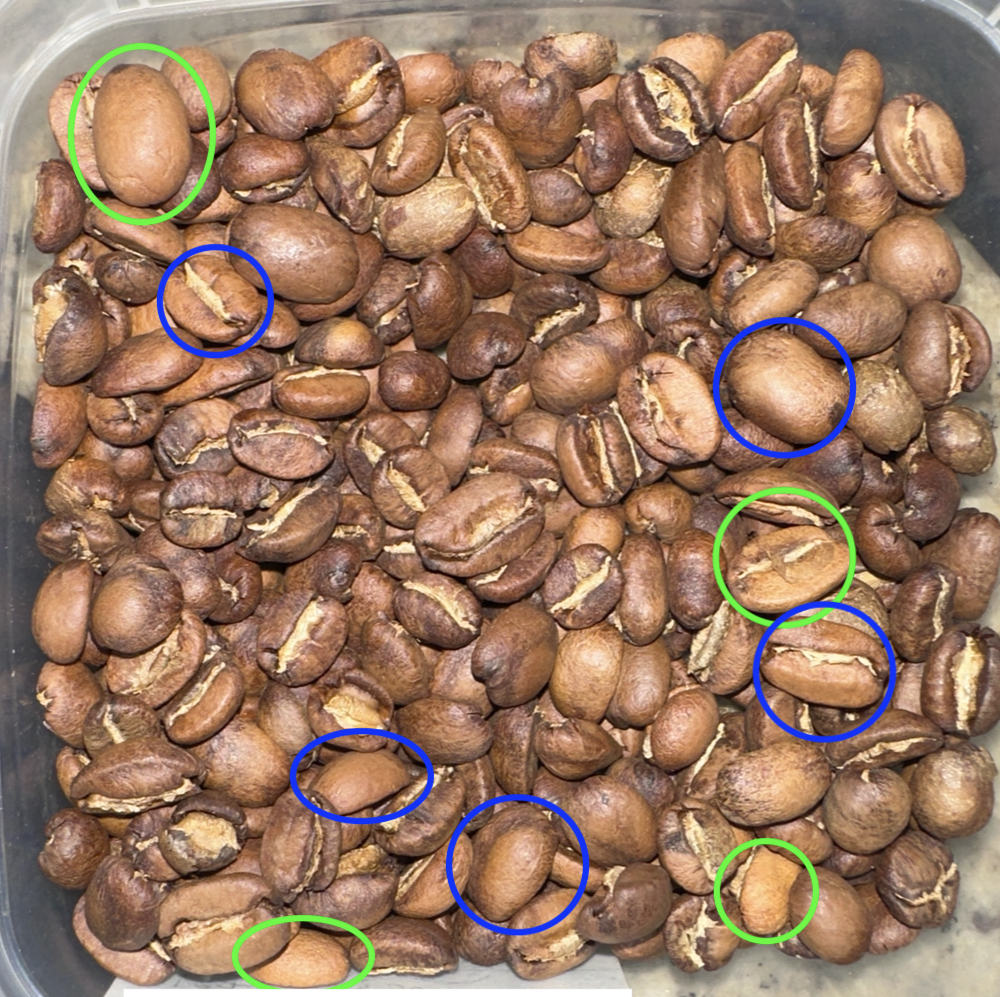

In the photo below, traditional quakers are circled in white, and the red circles represent pseudo-quakers. Please note I circled only a few representative quakers of each kind. I did not attempt to circle all of them.

Below: traditional quakers in green, pseudo-quakers in purple.

Two years ago I embarked on a mission with Mark to train ourselves to detect quakers. We would sort all quakers out of a sample of coffee and portion that sample into several cupping bowls. One bowl would be unsorted, one would have zero pseudo-quakers (fully sorted), and we would add one, two, or three quakers to other bowls. Then we’d scatter those bowls on a cupping table with several other coffees, taste blindly, and score.After a few such sessions we got pretty good at detecting pseudo-quakers. Perhaps a little too good, because we now have difficulty enjoying unsorted coffees.

What are quakers?

Quakers are immature coffee seeds. They can be the result of subpar plant health or nutrition, or picking underripe cherry. Quakers less dense and contain less sugar, protein, and starches than mature seeds do. As a result, quakers brown slower than mature seeds during roasting. Quakers can be difficult to identify and sort in green coffee, but are more obvious after roasting.

Producers can minimize quaker content by supplying coffee trees with adequate nutrition (starting with great soil health), picking only ripe cherry, and floating the cherries. It is far more efficient and affordable for producers to invest in preventing quakers than it is for roasters to remove quakers through sorting.

How quakers affect cup quality

How do quakers affect a cup of coffee? Have you ever described a coffee, perhaps from Brazil, as nutty? Quakers. Experienced an astringent cupping bowl? Quakers. Does a coffee have early onset of fade or baggy flavors in some cups but not all? Quakers. Quakers tend to be astringent, bitter, peanutty, and often grassy, grainy, or vegetal, depending on development level.

It’s difficult to quantify the impact of quakers on cup quality, but I’d estimate that if a cupping bowl contains one yellow quaker, the score will drop about one point. If 10—40% of a sample is pseudo-quakers (by weight), cup score will drop by 1/4—3/4 points. While the various industry scoring systems offer guidance for scoring quakers, not all quakers are created equal. Some quakers are barely noticeable in the cup, others single-handedly destroy an entire cup.

Quakers are not necessarily all bad. After all, people are used to tasting quakery coffee, and a bit of quaker-peanut flavor in an espresso blend meant for milk drinks may work well.

How many quakers are in coffee?

After becoming human quaker detectors, we naturally decided to sort as many quakers as possible from our coffee. Until that time, we never quite realized how many quakers of both types were in coffee. Average top-ten coffee from a recent COE competition? 15% quakers. Typical 87-point natural Ethiopian? 40% quakers — on a good day. Average 83-point, mechanically harvested “blender” from Brazil? It would be easier to count the non-quakers.

Last year we purchased two very expensive coffees from a well-known Colombian producer. The arrival coffees were so quaker-riddled that we had to sort and remove 40% of the coffees’ weight in order to bring the quality up to Prodigal’s standards. Needless to say, the pre-ship sample had hardly any quakers. This is a common bait-and-switch: provide a roaster with a perfectly sorted sample, hook them, and then ship an unsorted or poorly sorted version of the same coffee. It’s as if I you bought a new Toyota Corolla from me, but I deliver you a used car and tell you “but it’s still the Toyota Corolla.”

If a roaster does not use an optical sorter, the most frequent cupping note on your score sheet should literally be “peanut.” If you’re not noting peanut more than half the time in your cuppings, it means your brain is so used to associating peanut flavor with coffee that it is filtering out the peanut.

I’m sure many readers don’t believe that. But think about this: how often do you note “bitter” in cuppings? Probably not often. Yet every cup of coffee is bitter. Remember your very first cup of coffee? Bitter, right? So how did bitter go from the most prominent flavor you noticed to something you rarely notice? Simply put, if something is always present, your brain learns to partially ignore it.

As the bar for clean coffee gets raised over time, more roasters will sort their coffee. Once third-wave coffee drinkers get used to well-sorted coffee, serving peanut-flavored coffee will not go unnoticed.

I challenge the reader to try the quaker-detection training mentioned above a few times of over the course of a couple of weeks. Then, buy some Prodigal and a coffee of the same origin and process from some other third-wave roaster that doesn’t sort. Cup them blindly. Look for the peanut contrast. Once you learn to see it, you cannot unsee it.

How much should you sort?