We Are the Music Makers Podcast

Victoria Boler

Music education philosophy, ideas, and teaching strategies

- Sound Before Sight in Elementary General Music

Music is an aural artform.

The notation is a way to preserve the sounds, but the notation of the music is not the music.

How can we teach elementary general music in a way that centers music as an aural artform, and focuses on hearing and understanding?

What is Sound Before Sight?

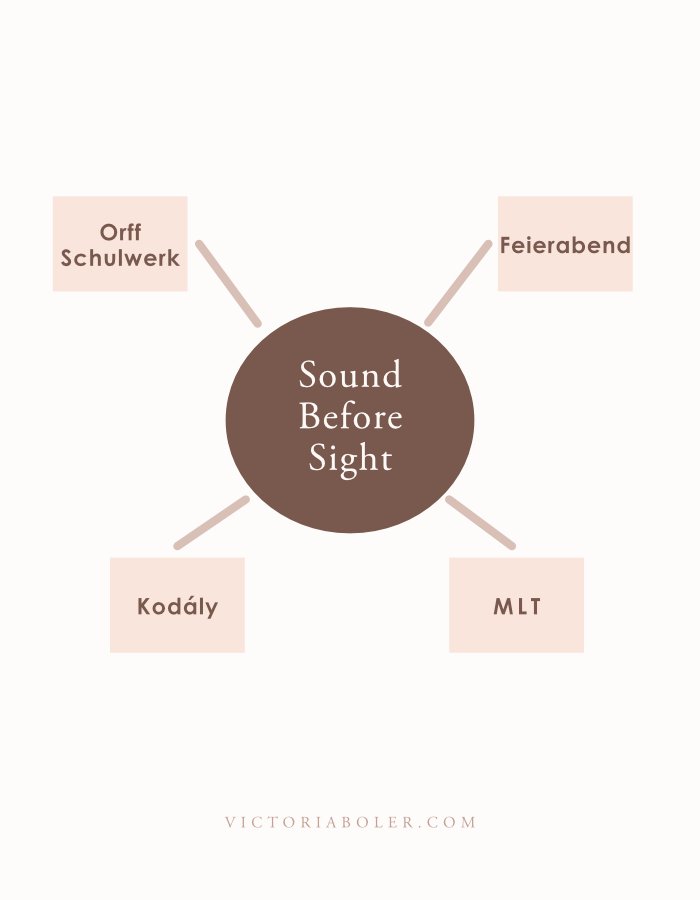

“Sound before sight,” or “sound before symbol,” or “sound-to-symbol” teaching is a principle many music education approaches follow, such as Orff Schulwerk, the Kodaly Concept, Music Learning Theory, Suzuki, and Feierabend.

With a sound before sight approach, we begin learning music through participatory interactions (listening, singing, speaking, playing, and moving) before we introduce visual notation and classroom vocabulary.

When notation is introduced, students have already built the meaning of the notation through experiences.

Learning Music Like a Language

Sound before sight is the way students learn to read a language, and while music is not a language, we can learn it the same way.

When a child is learning how to read, they have many years of experience just hearing language all around them. They also have years of speaking, and having interactive conversations in that language. When it is time for children to learn to read and write, they have an aural and oral context for the written language.

Imagine if we had children wait to speak until they could read and write. Imagine if children were only allowed to speak and have conversations using words they could read and write orthographically.

In the same way, we want young musicians to have time to interact with the aural and oral transmission of music in a true way before we add an unknown visual. We can use the sound before sight approach to emphasize musical experiences that lay a foundation for notational literacy.

Learning to hear vs to read: Is Sound Before SIght still Relevant?

To me, there’s something magical in sound-before-sight which I think makes it highly relevant in today’s music programs: this approach is much more about learning how to hear rather than learning how to read.

The emphasis is on developing students’ aural skills, which will serve them well in any field of music. Regardless of which musical pathway students end up on outside of class, the ear training as the foundation of the sound-to-sight approach will be useful.

When students engage in something like informal learning processes, they’ve developed the aural discrimination to hear a song and learn it by ear, or read a chord chart. If they go on to be an audio mixer, they’ve honed their aural sensitivity to specific musical qualities of each track. If they go on to be an instrumentalist playing a film score reading standardized Western notation, they have the aural training and a way to mentally link the aural event to a visual representation.

To me, this approach is highly useful and very relevant because it develops aural skills and analytical thinking that students can employ in any field of musicing.

Learn more about the National Standards for Music Education

Pestalozzi and Sound Before Sight

The importance of a “sound before sight” approach was developed through the work and followers of Heinrich Pestalozzi. Pestalozzi was a Swiss educator in the 18th and 19th century. He believed in the importance of experiences and sensory-based learning, called Anschauung.

In music education, our use of this principle has evolved from its early use in American public schools which focused primarily on singing and vocal development as the entirety of the school music program.

Today Pestalozzi’s principle continues to be applied differently in music programs with music education approaches such as the Kodaly concept, Orff Schulwerk, and Music Learning Theory.

Sound Before Sight Examples:

Experience First

Pestalozzi advocated that children should learn through direct, concrete experiences. This experiential education focused on “Anschauung,” or sense intuition, and learning through observation, exploration, and hands-on activities.

In this constructivist model, the student is an active participant in their own learning, as opposed to a passive participant who receives information from the teacher.

What Does Experience First Look Like in Music Education?

In practice, we can think of sound before sight as actually active experience before sight.

In this approach to teaching and learning music, we center learning experiences around active musicking. That is, active involvement in musical tasks like singing songs, speaking rhymes, playing games, playing instruments, and moving.

The way to learn music is through musicking - embodying musical experiences. Musical comprehension is built in an active embodied experiential context.

When it’s time to actually pull musical knowledge from these experiences, we need a place for the melodic or rhythmic or form or textural understanding to live aurally.

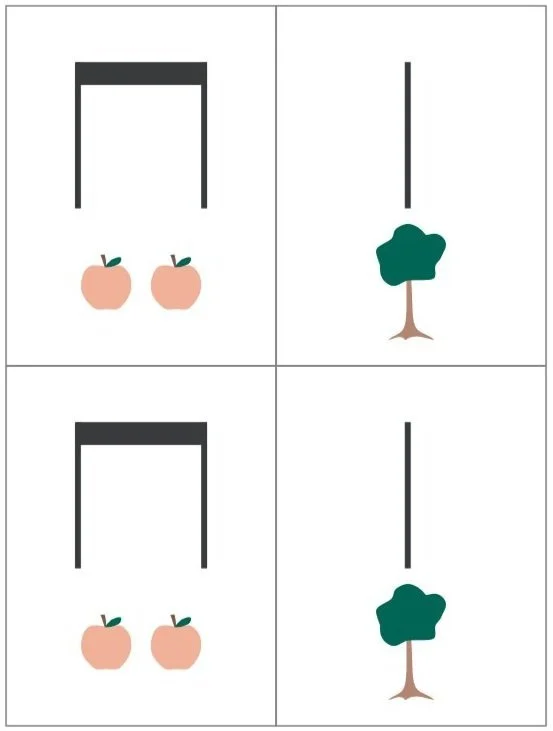

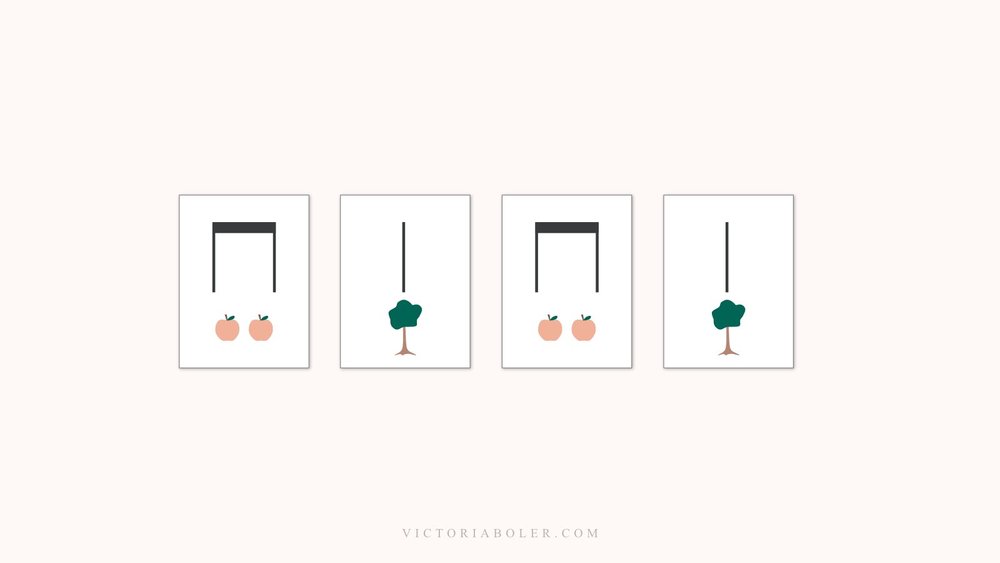

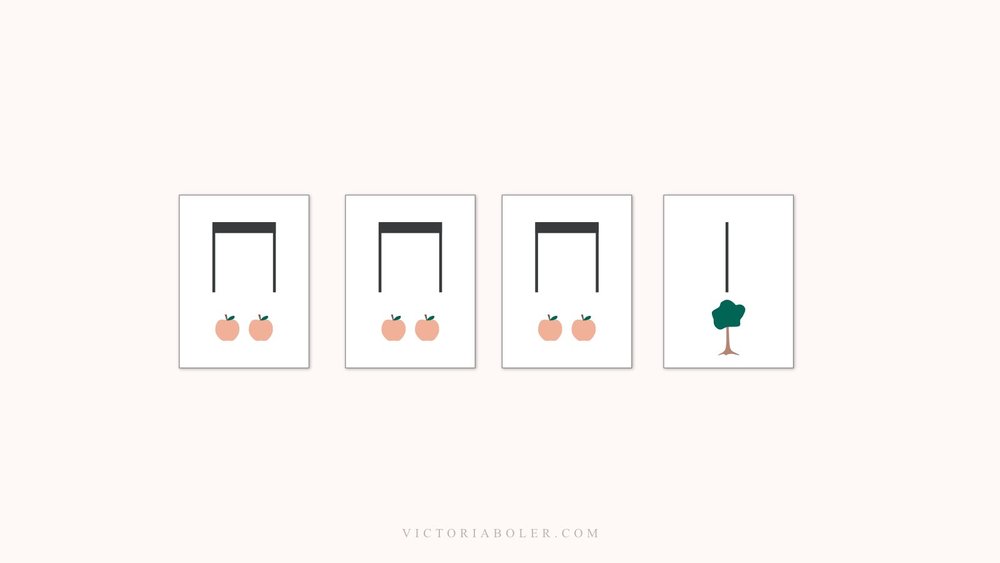

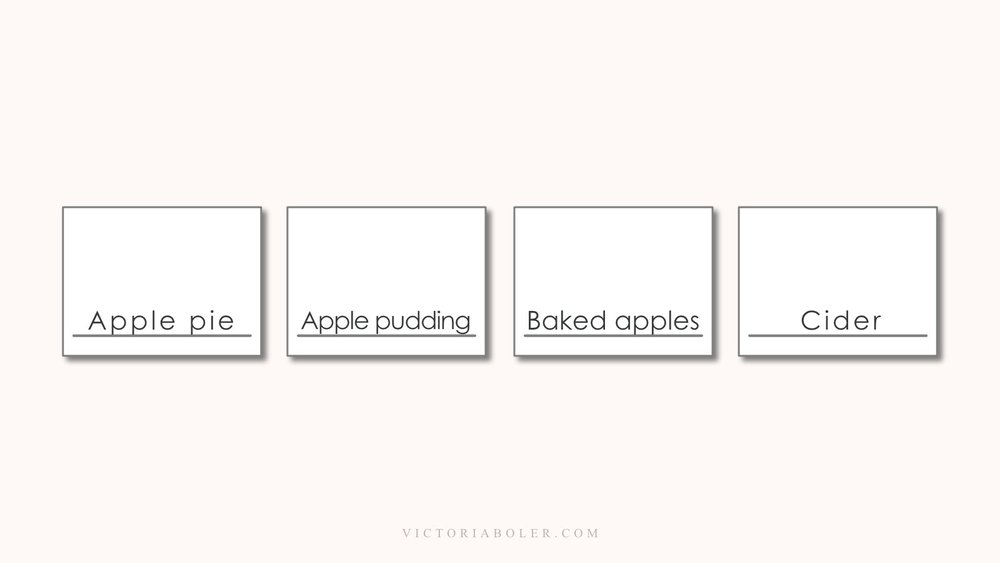

Experience Example 1: Apple Tree Game

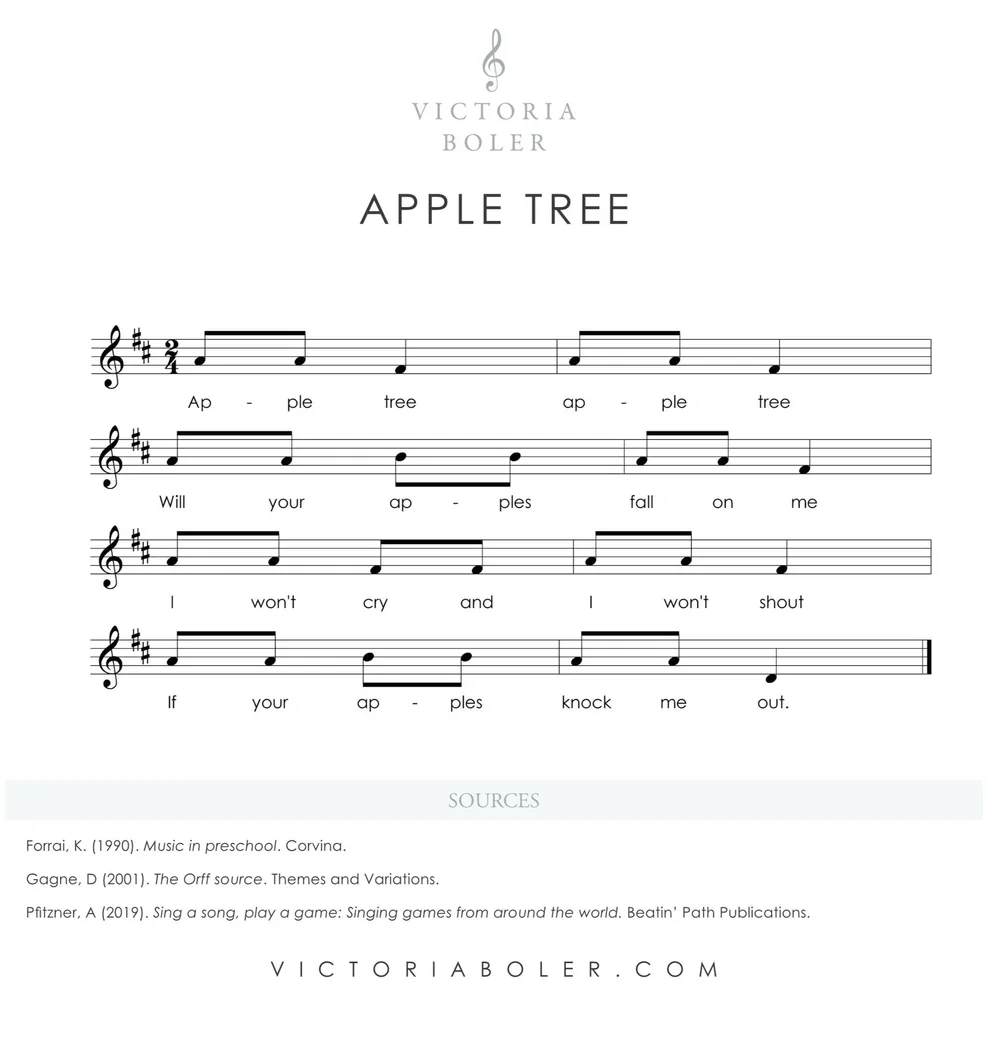

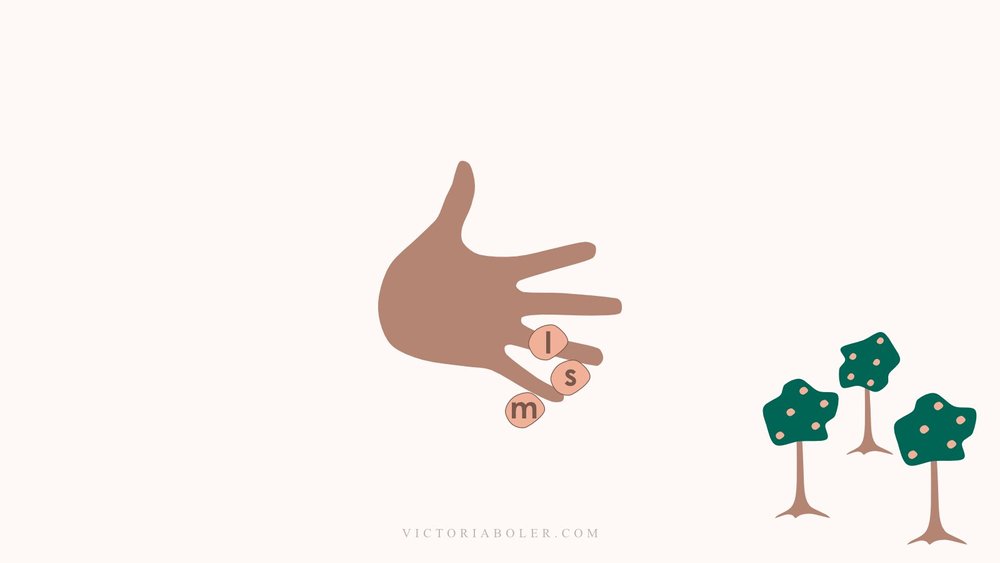

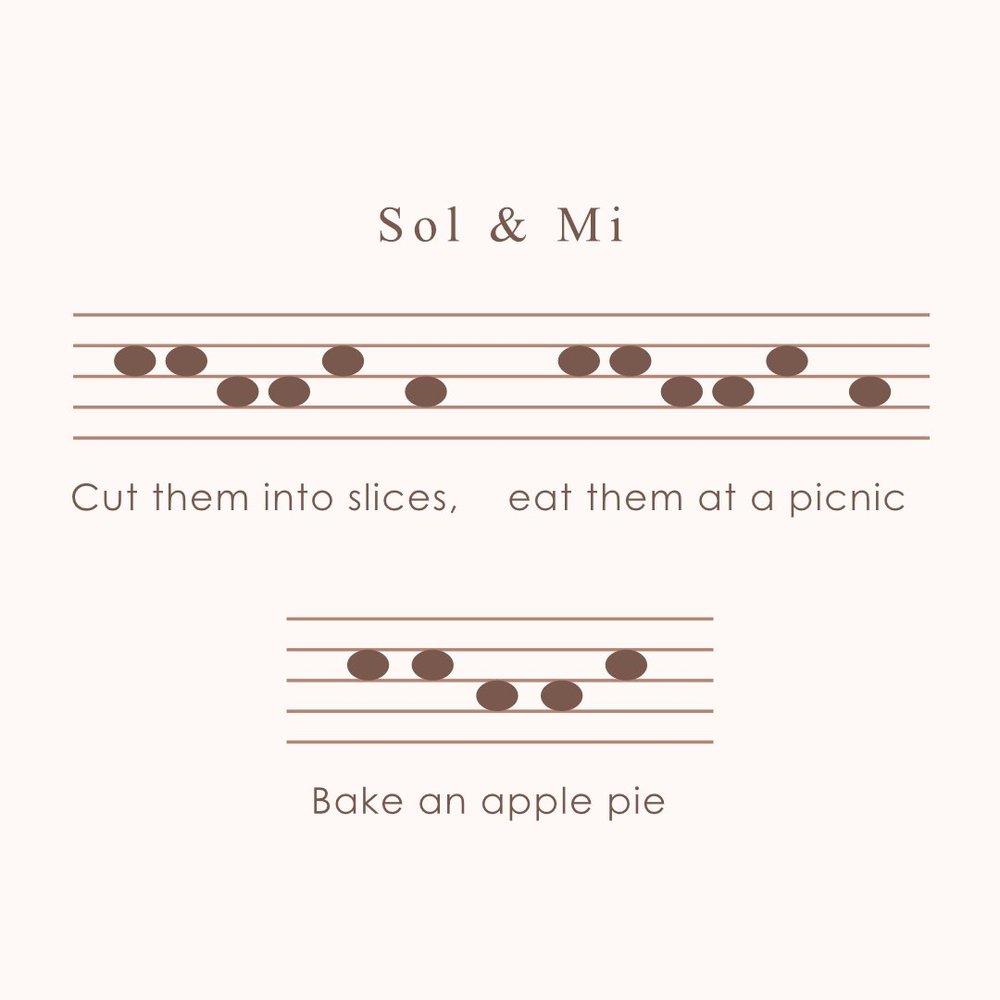

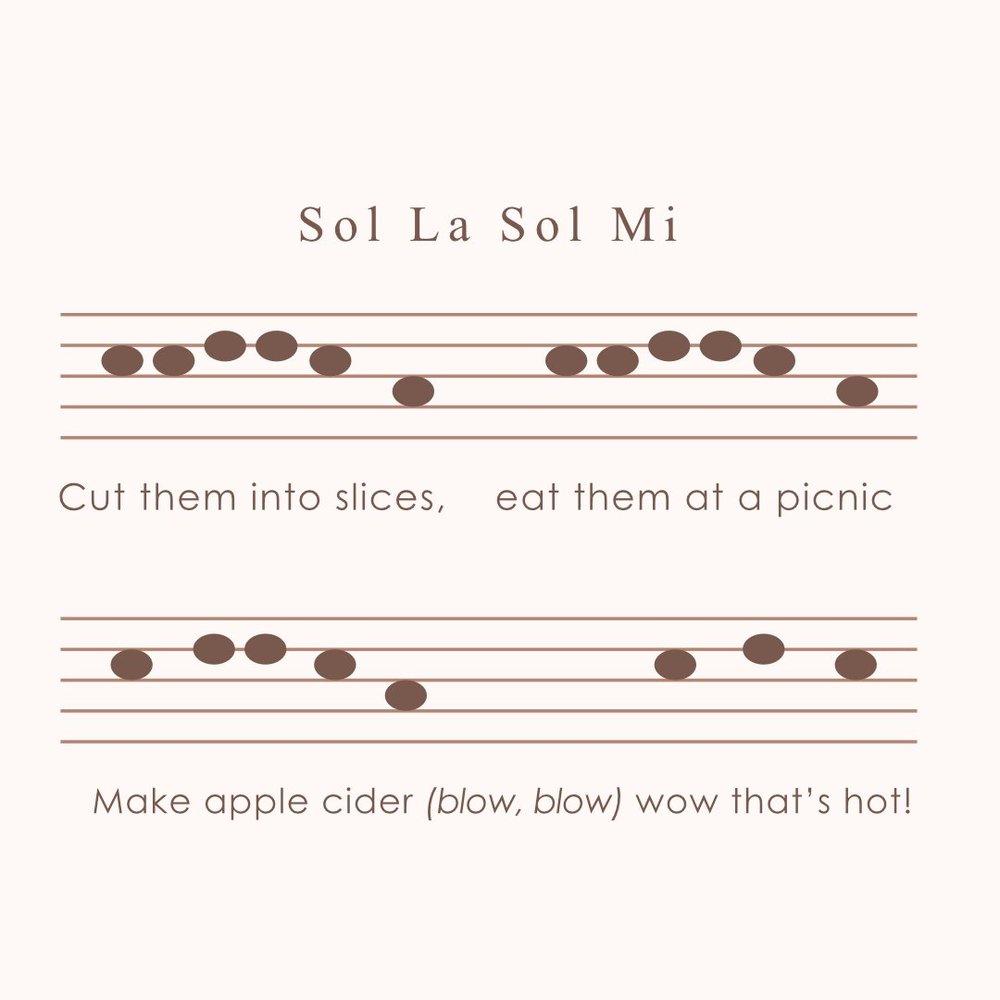

This is one application out of many possible uses of sound before sight: let’s imagine that in 1st grade we want to teach a tritonic melody, in this case sol, la, mi.

Instead, we’re going to start with an active experience - in this case, a singing game.

Directions:

There are many different versions of this singing game!

In the one I use, two students connect their hands above their heads to create a tree. The rest of the class walks in a circle under the tree while they sing the song.

At the end of the song, the players creating the tree lower their branches and capture one student. That student becomes an additional tree with the teacher and the game begins again. Each round of the game creates more and more trees.

Experience Example 2: Vocal Improvisation

We can also use improvised singing conversations to experience sol, la, mi without using those names.

Singing the question with a sol, la, mi melody, we’ll ask students what they would do with all the apples that fell from the tree.

Students sing their responses back with a sol, la, mi toneset. Examples might be, “I would take them to my grandma,” or “I would share them with you,” or “I would peel them,” etc.

At this point in the teaching and learning process, students are using the toneset to sing, move, and improvise. Our emphasis is on creating contextual musical experiences.

Sound Before Sight Examples:

Known to the Unknown

Interconnected to the idea of experiencing first, another central belief from Pestalozzi that we use today is moving from the known to the unknown. Pestalozzi believed that Anschauung needed to be experienced before the key word in the lesson was used.

Moving from the concrete to the abstract, and the familiar to the unfamiliar, learning begins with an existing set of knowledge and experiences. We use those existing sets of knowledge and skills to make comparisons and connections to new things we encounter. We use our known informational landscape to investigate an unknown element.

What Does Known to Unknown Look Like in Music Education?

We want student musicians to link known musical concepts to new musical sounds.

Using this strategy of known to the unknown, students figure out new rhythmic and melodic elements by first categorizing them into what they are not. Does the melody go higher than the pitches we know? How much higher? How much lower? We can hear that a piece of melodic information is missing because we compare the new sounds to known sounds.

The sequence we use becomes the set of known musical concepts students will compare new musical sounds to.

Learn more about a Scope & Sequence for elementary music here

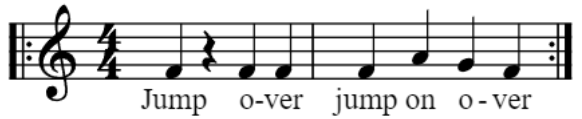

Known to Unknown Example 1: Aural Decoding

Let’s imagine we want students to aurally identify a new pitch higher than their known pitches, sol and mi. This is where we will link the new sound (la) to the known sounds (sol and mi) and where our musical sequence is so useful.

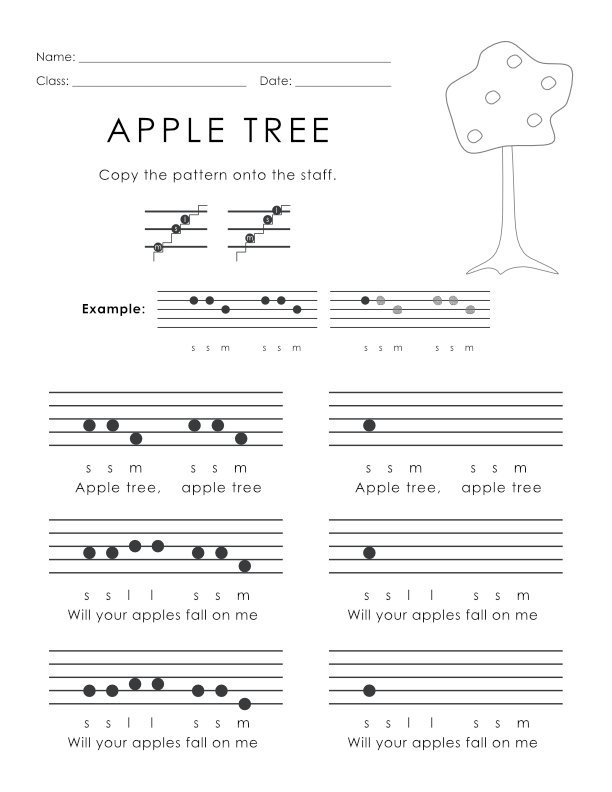

Sing the song and play the game to Apple Tree

Standing still, sing the first four beats on a neutral syllable while “painting” the melody (tracing the melodic contour in the air)

The teacher sings the question with a sol mi toneset: Those sound like pitches we know. In this class, what do we call them? (sol and mi)

Sing the first four beats on solfege with body solfege signs or Curwen hands signs

Sing the next set of four beats on a neutral syllable while “painting” the melody

Were all of those pitches sol and mi? (no) What was different about that melody? (answers may be divergent - the melody went higher)

Sing the first eight beats on a combination of solfege and a word students choose to describe the new pitch, like “up,” “sky,” etc.

Sol sol mi, sol sol mi, sol sol up up sol sol mi

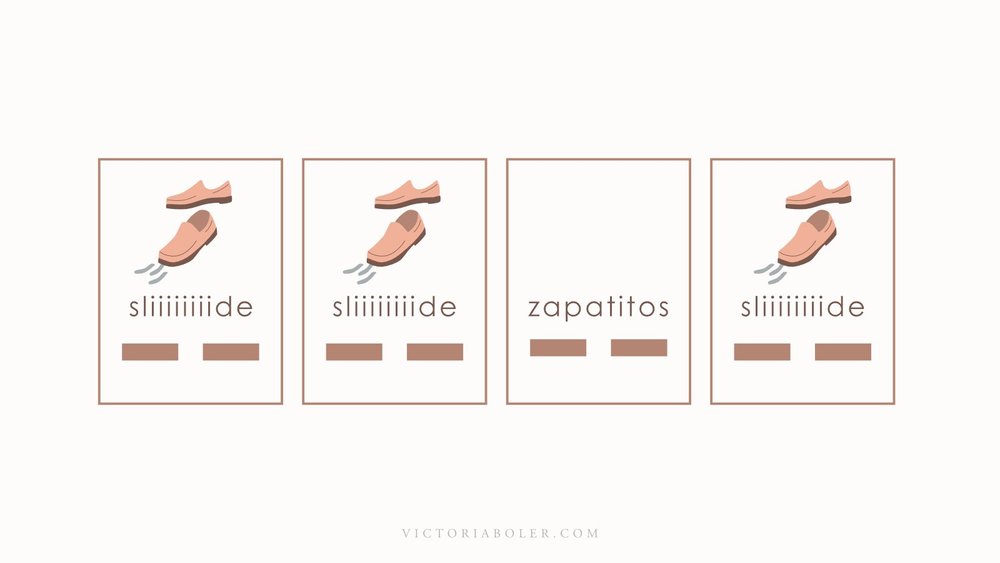

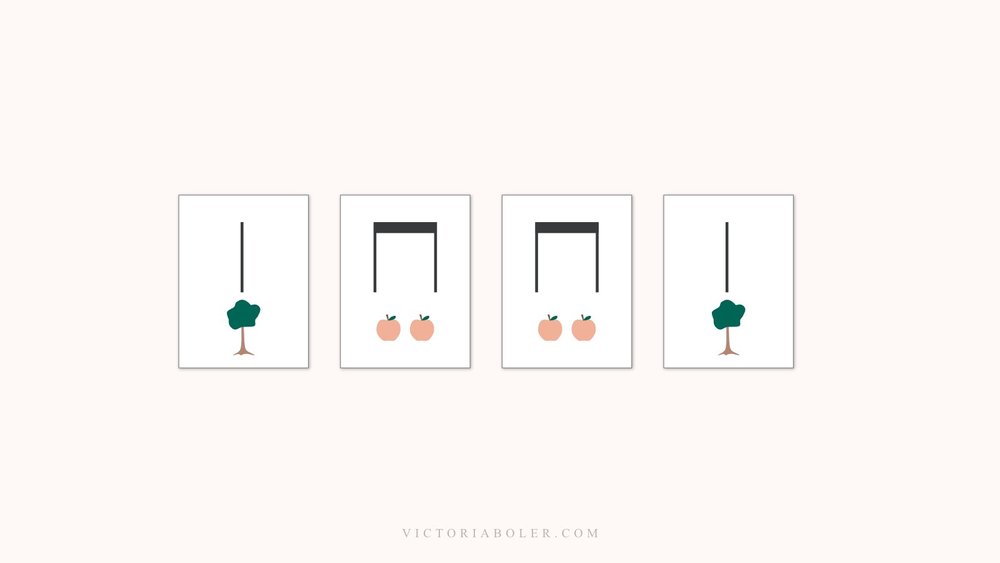

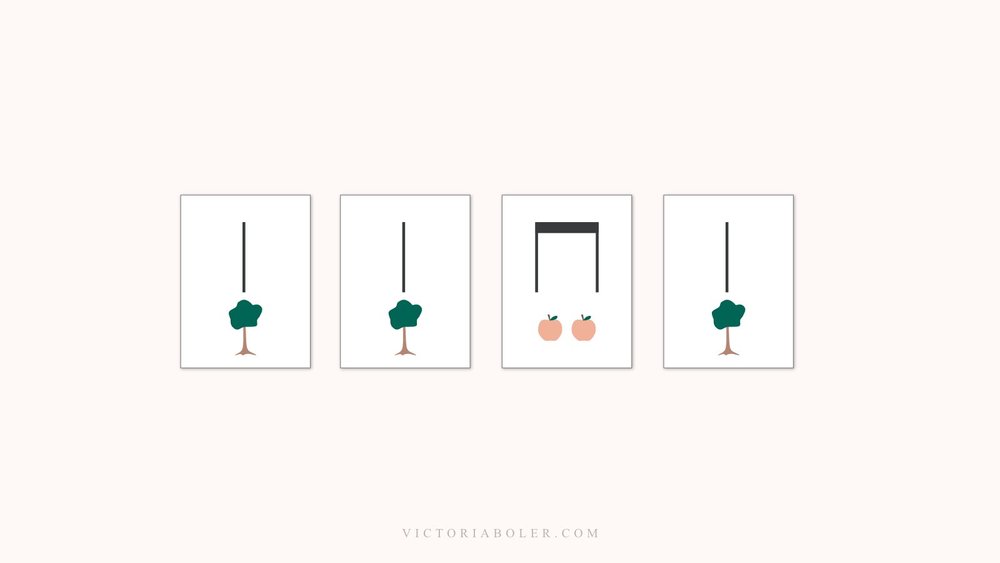

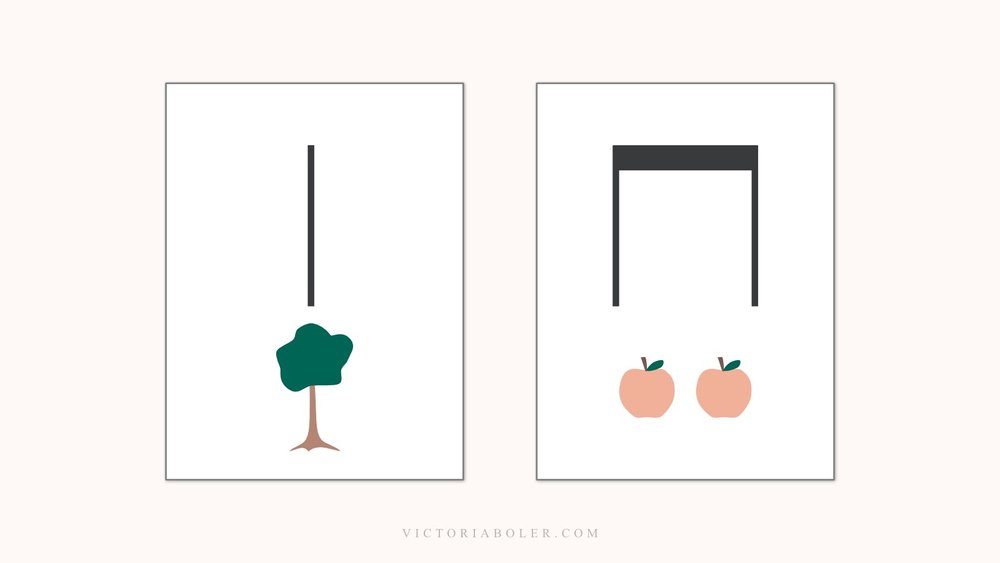

Known to Unknown Example 1: VIsual Representation

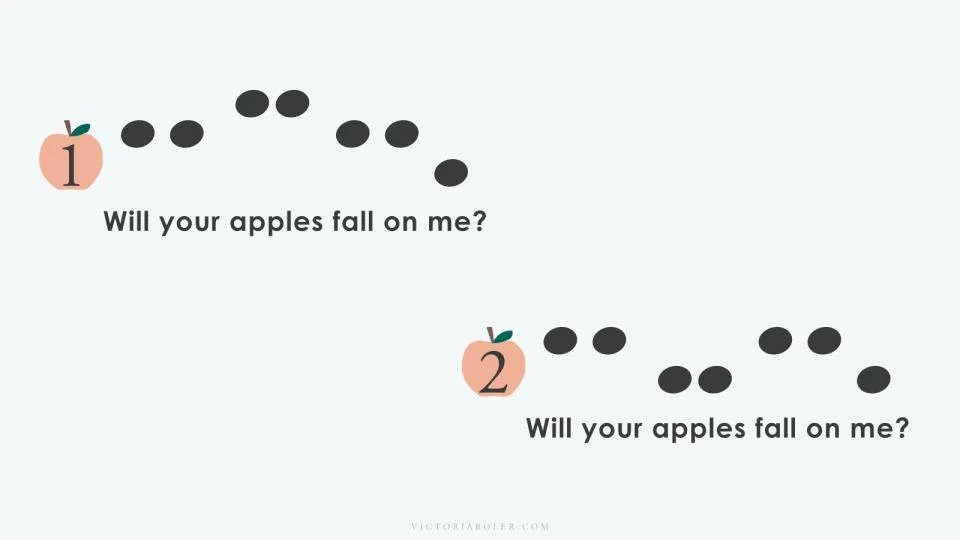

Students have analyzed the melody and found a new high pitch in the phrase.

At this point they might link the new sound to a visual representation of the sound.

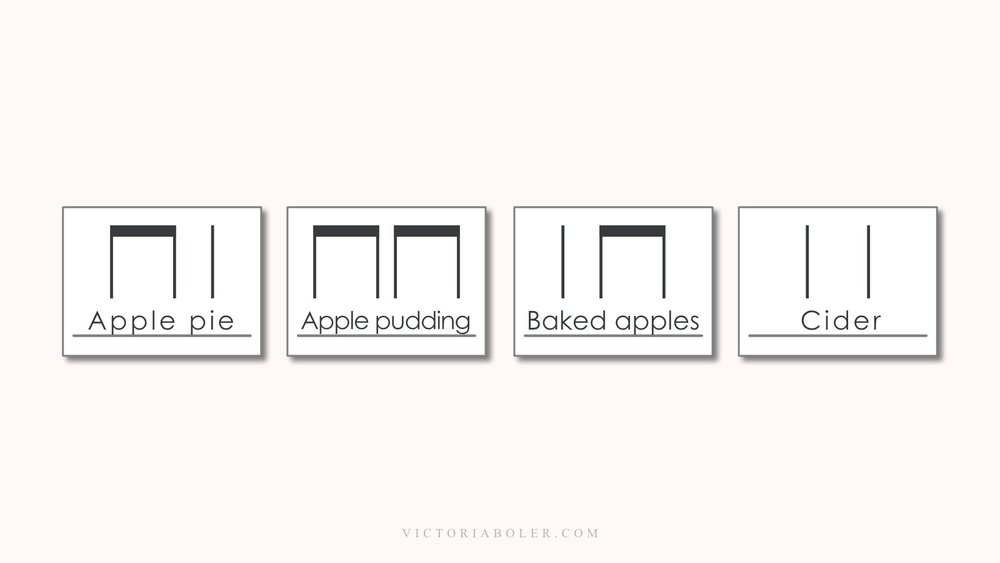

Looking at the board, students work with a shoulder partner to decide which image shows the melody most accurately. Students show their answer by holding up a 1 or a 2, then turn to a shoulder partner and discuss their answer.

Other Ways to Visually Represent a Melody

There are so many more options for visually representing a melody in a sound-to-sight model!

Here are a few extras to consider….

Students can trace the melodic contour in the air. (They’ll do this without the teacher’s assistance.)

Students can place manipulatives like small erasers or Lego blocks to show the melodic contour on the floor in front of them.

Students can use a pencil to write the melodic phrase above the words of the text in an exit ticket. (When I do this, I also like to ask students why they chose to write the melody the way they did.)

Students can help the teacher or another student drag the target pitch higher or lower on the board by pointing up or down. Here are a few examples of what that can look like with la, do, and re:

After these interactions, students have (1) used the new pitch in a singing game (2) improvised with the new pitch (3) aurally identified the new pitch, and (4) notated the new pitch.

When the teacher introduces the classroom vocabulary for the new pitch, la, and how to write it on the staff, students have already constructed what the new solfege pitch means in a melody.

Sound Before Sight in Music Education

This experiential process allows students to connect musical components like melodies, rhythms, and dynamics with their existing auditory experiences. As a result, students develop a solid foundation in aural skills because they internalize music before they encounter its visual symbols. Whether those symbols are in the form of chord charts, tablature, the Nashville Number System, or standardized Western notation, sound before sight helps students interpret notation meaningfully when the time comes.

3 July 2024, 10:22 am - Picture Books to Sing in Kindergarten Music Class - From Epic Books

Here is a list of books to sing from Epic Books! At the time of this post, all these books are live, and available on the free plan.

This is an accompaniment post to this podcast episode about how to create activities around picture books.

Let’s get singing!

Singing Books about Animals, Insects, and Arachnids

Cat Goes Fiddle-I-Fee

By: Harriet Ziefert

Illustrated by: Emily Bolam

This cumulative song is so fun to sing! Throughout the story we collect more and more animals, making our song longer and longer.

The Itsy Bitsy Beetle

By: Artie Bennett, Wes Magee

Illustrated by: Tomislav Zlatic

After Itsy Bitsy Spider goes up the waterspout, Itsy Bitsy Beetle has his own adventure in the snow!

The Itsy Bitsy Spider

By: Scarlett Wing

Illustrated by: Rob McClurkan

Scarlett Wing extended the story of The Itsy Bitsy Spider to be a tale about perseverance. At the end of each page the author wonders if Itsy Bitsy Spider goes up the spout again… read to find out!

Mary Had a Little Lamb

Illustrated by: Hazel Quintanilla

Quintanilla has a knack for reimagining the story of children’s songs through her illustrations. In this classic song and nursery rhyme, Mary is a lamb herself, going to a school run by a hen and playing with bunny, bear, and dog friends.

Oh Where Oh Where Has my Little Dog Gone

Illustrated by: Hazel Quintanilla

This song is well-loved by many children already, but Quintanilla gives it a new story with the illustrations. Join a loveable family of dogs as they play a fun game of hide-and-seek. Where could the little dog be?

Over in the Meadow

Illustrated by: Jill McDonald

This is one of my all-time favorite books to sing! I love using it on the first day of school. Students quickly pick up on the call-and-response form of the dialogue.

The Wheels on the Bus

By: Scarlett Wing

Illustrated by: Jannie Ho

This classic children’s song gets a fun twist from author, Scarlett Wing! In this version step on the bus with circus animals, and sing all through the town.

Sing a Book Up in the Sky

Star Light Star Bright

By: Artie Bennett, Melissa Everett

Illustrated by: Oksana Pasishnychenko

This book extends the classic nursery rhyme, adding different things a parent wishes for their child.

In the classroom, we can choose a few pages to sing together, then students can take turns singing their own wishes.

Twinkle Twinkle Little Star

By: Ann Taylor and Jane Taylor

Illustrated by: Katherine Duffy

Duffy illustrates the classic text of “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” by sisters Ann and Jane Taylor. This is a great opportunity to introduce students to the poem’s full text!

Twinkle Twinkle Little Star

By: Scarlett Wing

Illustrated by: Stacy Peterson

Author Scarlett Wing adds charming additional verses to this well-loved children’s song. Each page is set in a different children’s story: Little Red Riding Hood, Cinderella, Jack and the Bean Stalk, etc.

Sing a Story about Nature

Jack and Jill

Illustrated By: Hazel Quintanilla

Hazel Quintanilla has illustrated several books in this collection! This is the classic text of Jack and Jill, acted out by two adorable mountain goats.

I Love the Mountains

Illustrated By: Haily Meyers

Speaking of mountains, Haley Myers set the classic song, ‘I Love the Mountains” to beautiful illustrations in this book! In addition to singing the song, we can also consider creative movement opportunities by asking students to act out the different scenes in the book: mountains, meadows, water, etc.

Sing About Water

There’s a Hole in the Bottom of the Sea

By: Jessica Law

Illustrated by: Jill McDonald

Jessica Law took a different spin on this classic children’s song! This time, Law uses each new verse to sing about a different animal: snail, squid, shark, etc., and each new animal has a different place in the food chain of the ocean!

Rain Rain, Go Away

By: Melissa Everett

Illustrated by: Carrie Wendel

In this book, children start the song by singing about how they wish the rain would go away so they could play outside. By the end of the book, the children realize they can play outside in many different kinds of weather! They decide the rain can stay after all.

Down by the Bay

By: Kim Mitzo Thompson, Karen Mitzo Hilderbrand

Illustrated by: Roberta Collier-Morales

This is a well-loved children’s song, and such a fun way to work on echo singing! Collier-Morales illustrated the book cumulatively, so each time we sing about a character, they stay on the page. By the end of the book, we have collected a host of silly characters down by the bay.

Down by the Bay

By: Kim Mitzo Thompson, Karen Mitzo Hilderbrand

Illustrated by: CIA Students

This second installment of “Down by the Bay” is only slightly shorter than the first version, which is great for classes where we are short on time!

Books to Sing On the Farm

A Farmer’s Life For Me

By: Jan Dobbins

Illustrated by: Laura Huliska-Beith

While this isn’t technically a book to sing, the rhyming text is delightful. Dobbins added the repeated refrain, “1 2 3 it’s a farmer’s life for me” throughout the book. Take this opportunity to compose a simple melody to this repeated phrase and have students sing it with you!

Old MacDonald had a Farm

By: Kim Mitzo Thompson, Karen Mitzo Hilderbrand

Illustrated by: Patrick Girouard

The classic! Sing this lively and well-loved song at the end of class, and then consider exploring the variations listed below.

Old MacDonald Had a Band

By: Scarlett Wing, Dan Taylor

Illustrated by: Dan Taylor

Students may already know that Old MacDonald had a farm… but do they know about the band? Join these animals as they get ready to put on a show at the end of the book. In a future reading, consider talking about what students notice about the book, and how the instruments make sounds.

Old MacDonald Had a…. Zoo?

By: Iza Trapani

Iza Trapani has several delightful children’s stories to sing, and luckily for us, this one is available on Epic Books! In this story, students follow Old MacDonald as he tries to go about his day, taking care of his cow as well as his kangaroo, elephant, zebras, and more!

Singing Books About People

Diddle Diddle Dumpling

By: Melissa Everett

Illustrated by: Imodraj

After John goes to bed with one shoe off and one shoe on, we learn about other children in this nursery rhyme adapted by Melissa Everett.

I Know an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Fly

By: Alan Mills, Rose Bonne

Illustrated by: PisHier

In this silly (and somewhat morbid) children’s classic, the old lady swallows a fly and proceeds to swallow a host of other animals.

This Old Man

By: Kim Mitzo Thompson, Karen Mitzo Hilderbrand

Illustrated by: Laura Ferrar-Close

Students will love helping us count to ten as we tell the story of an old man who loves to play his rhythm sticks all over town! This is a great story to lead into or out of another rhythm stick activity in class. Students can also quickly pick up the repeated refrain at the end of each page and sing along.

Bonus: Sing a Book About a Beat!

We Got the Beat

By: Charlotte Caffey

Illustrated by: Kaitlyn Shea O'Connor

This book deserves to be in a category all on its own!

The text of the Go-Go’s song “We Got the Beat” is set to lively illustrations. Read the book, then sing along with the recording and move!

1 July 2024, 10:05 am - Upper Elementary Music Games

Singing games are a beautiful way to increase student participation and teach musical skills in any grade level!

When we choose games for upper elementary students, we can look for engaging and active games that incorporate competition in a student-friendly way.

Let’s look at examples of singing games that upper elementary students love: Deedle Deedle Dumpling, Doña Araña, Vamos a Jugar, El Florón, and Big Fat Biscuit.

Then, we’ll explore two research studies about singing games in upper elementary music. These two studies can help us frame why these games are so important to students in this age group, and they can have implications for the way we approach learning activities for upper elementary students in general.

Let’s sing!

To find these songs, we’ll set our game level to upper elementary and then select the categories:

Chasing / tagging / racing

Elimination

Jumping

Objects

Deedle Deedle Dumpling

This is an old nursery rhyme with two games for chasing, tagging, and racing.

Chasing, Tagging, & Racing Game:

The game is an addition to another song.

Formation: Students take hands to form two concentric circles. A single shoe is on the floor inside the smaller circle, and two students (John 1 and John 2) stand outside the circle.

Directions: Secretly, the teacher chooses two pairs of students to be the doors to the house.

All students sing the song and walk around the circle in opposite directions. At the end, the secret pairs of students raise their hands to create an entry to the middle. Both Johns race to get to the shoe first.

Alternate Game:

Aimee Pfitzner shared a different game in her book, “Sing a Song, Play a Game.”

Formation: Students stand in a circle.

Directions: Students sing as one student walks around the outside. At the end of the song, the person lands behind two people. Those students each take off one shoe and race around the circle in opposite directions. The person who gets back to their place and puts their shoe on first wins.

Listen to Aimee Pfitzner share more about her favorite singing games here

Doña Araña

I love this song for many grade levels, including upper elementary!

You can read about how to use Doña Araña for different grades here.

Chasing, Tagging, & Racing Game:

Formation: Students create a circle (spider web) and connect hands. One student is the fly inside the spider web. One student is the spider outside the spider web.

Directions: Secretly, the teacher chooses a pair of students to create a doorway at the end of the song.

Students sing and walk around the circle with hands connected. At the end of the song, the chosen students raise their hands to create an opening in the circle.

The fly must escape the spider web through the opening and get to the safe zone before being tagged by the spider.

Vamos a Jugar

This clapping elimination game is one of my favorites! It’s so easy to get started, and students love it.

Clapping Elimination Game:

Formation: Students sit in a circle with palms face up. The right hand goes on top of the neighbor’s left hand.

Directions: As the class speaks the rhyme, the steady beat is clapped around the circle. At the end of the rhyme (at the word, “diez”) the person on whom the beat lands is out unless that person pulls their hand away in time.

El Florón

There are several variants of this well-loved song from Puerto Rico and several different versions of the game!

Here’s a version for upper elementary.

Object Passing Game:

Formation: Students stand in a circle.

Directions: Students pass a ball around the circle while singing the song. At the end of the song, the person holding the ball sits down and is out of the game. The rest of the class sings the song again, continuing to pass the ball over the empty spaces left by students who sit down.

To increase the difficulty, students who are seated may reach their hand up to try to swat the ball away from those who are passing (Newlin, 2016).

Big Fat Biscuit

This song from the Sea Islands is a huge hit with upper elementary!

When I introduce the song, I normally begin by having students sing an ostinato as I sing the main song:

Jumping Game:

Formation: Three students line up shoulder-to-shoulder.

Directions: Students sing the song. At each “chew-belew,” students take turns jumping out as far as they can. At the end of the song, the person who has jumped the furthest is the winner.

Why Singing Games?

When we use singing games in upper elementary music, we can increase students’ motivation, engagement, and participation.

More strategies for increasing student engagement

Why is that?

Let’s frame our thinking around two studies that may have some implications for our work in upper elementary music: both in how we approach singing games, and how we approach learning activities for this age group in general.

Competitive vs Non-Competitive Singing Games:

In this 2016 study from Christopher Roberts, the researcher wanted to know if 4th grade and 2nd grade students preferred competitive or noncompetitive singing games.

What do you think he found?

Students in this study preferred competitive singing games over non-competitive singing games.

That finding may feel intuitive to us - we may have expected students to prefer competition based on our own experience teaching this age group. However, what may be more interesting is why students said they enjoyed competitive singing games more. And that reason was a kinesthetic activity - the movement piece was the reason students gave for enjoying these games more.

Even for the students who said they preferred the non-competitive singing game, the reason was the same - they liked the movement.

The Importance of Movement:

This was what the same researcher found in this earlier study when he wanted to know when 4th grade students were the most interested in music class.

Here’s a quote from one of the 4th grade participants in the earlier study describing their experience with moving in music class:

“You know, because we’re kids, we like to be active, instead of just sitting there, saying sol-la-do. And you notice how all of us, most of the time, are moving around, not sitting still.”

This researcher also used videos of class as part of the dataset.

Reviewing the videos, one of the things the researcher noticed is that when students were preparing for a concert, there was more off-task behavior - staring into space and not singing, playing with shoelaces, etc. Then when the researcher switched to an active singing game, the engagement level went way up. More students were singing, students seemed to be more focused, and more of the class was engaged.

Movement in Music

What might this research suggest to us as upper elementary music teachers?

Movement is really important to this age group!

When we construct learning activities for upper elementary, we can choose to center movement as one of our teaching strategies. These students are not too old to move in music class - in fact, engaging and active singing games are exactly how many students enjoy spending their time with us.

How to Cite this Post:

Boler, V. (2024, May 9). Singing games for upper elementary. https://www.victoriaboler.com/blog/upper-elementary-singing-games

Research Cited:

Roberts, C. (2015). Situational interest of fourth-grade children in music at school. Journal of Research in Music Education. 63(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/0022429415585955

Roberts, C. (2016). ‘Wanna race?’: Primary student preference for competitive or non-competitive singing games. British Journal of Music Education 33(2).https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051715000236

8 May 2024, 10:59 am - Barred Instrument Exploration Activities

Let’s look at some ways to introduce the instruments through a few different pathways: a fingerplay, a circle dance, and a picture book.

We’ll prioritize using them respectfully and playfully.

We’ll highlight playing technique to students who are new to these instruments, or to students who need a refresher.

Let’s jump in!

-

JUMP TO ACTIVITIES

Barred Instrument Exploration: Setting the Tone

Here is a quick guide to getting started with barred instruments.

Instrument Mechanics

Which is the high side? Which is the low side? Students who are new to the barred instruments can need guidance on how to tell the difference.

Barred instrument exploration allows us time to get acquainted with how the instrument is constructed.

Our instruments are shaped like a mountain. The narrow side is on top, the wide side is on the bottom. Even when we move the instrument around, no matter how we look at it, the high and low sounds of the instrument stay the same.

Holding the Mallets

I ask my students to pinch the mallet with their index finger and thumb, then wrap their other fingers around the mallet, then turn their elbows out slightly like they’re riding a bicycle.

We want to avoid students playing the instrument with their thumbs facing up. Instead, we want the top of their hand to face the ceiling as they play.

Playing Technique

When we give space for barred instrument exploration, students have time to figure out how they need to maneuver their hands to get the best sound.

Students should play with a gentle bounce in the middle of each bar. Periodically dropping in verbal cues with this imagery can be helpful. For example, instead of exclusively saying “Play this rhythm on G,” we can say “gently bounce your mallets to this rhythm on G.”

Getting to the Instruments

Take time to model and practice how to physically get to the instruments.

We always walk around the instruments. We don’t walk over. We don’t walk through.

Care and Respect

These instruments are very special! They may have made a journey to get to the music classroom, and were perhaps helped by grant funding from a particular organization, school funding, community donations, etc. Telling students the story of the instruments - how they got to be here, how valuable they are, etc. sets the one for how we approach them with care.

These instruments are tools we use to express musical ideas. We’re ready to use them when we show that we’re ready to treat them with care.

Culture of Play

In our first invitations at the barred instruments, we can infuse the interactions with a tone of play. Through the activities we’ll talk about today, students have opportunities to “noodle” around, and create their own sounds within our parameters.

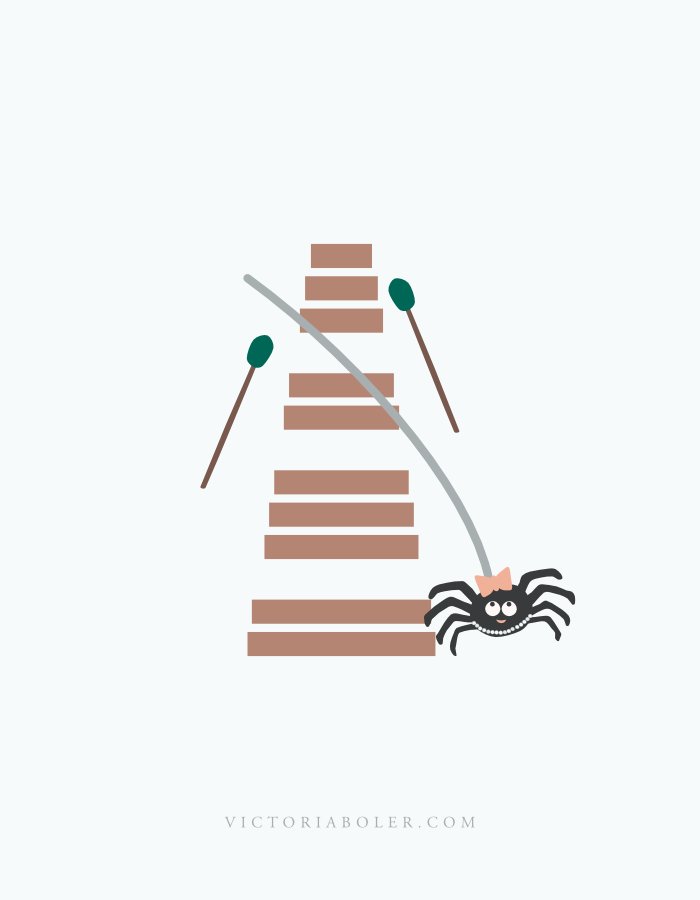

Barred Instrument Exploration with Dona Arana

It’s no surprise that I’m excited to use Dona Arana!

In this sequence, after we sing the song with the fingerplay, we’ll use mallet exploration as the first step.

Dona Arana Overview

Mallet exploration

Barred instrument exploration

Barred instrument sound story improvisation

Step 1: Mallet Exploration

Sing the song and act out the story with mallets

The teacher sings and acts out the story with mallets. Students follow along.

A few students at a time use mallets and imitate the teacher. At the end of the song, they pass the mallets off to someone who was following along.

Eventually, every other student has a set of mallets.

Perhaps in another class, the teacher wonders, how could you tell the story of Dona Arana with your mallets, but change how you move your mallets? Still copy me, but find some small changes.

Repeat the activity, students find their own way to gently use the mallets to tell the story in a different way.

Step 2: Barred Instrument Exploration

With a few instruments set up vertically, the teacher models what it sounds like for Dona Arana to walk at the bottom of the instrument, then spin her web up, dance at the top of the instrument, then gently come back down.

A few students at a time come to an instrument and play the song with the teacher.

Doña araña se fue a pasear.. Let’s go for a walk on our instrument. You can do what I do, or you can walk a different way.

Hizo un hilo y se puso a trepar…. Let’s spin our webs up….. You can spin your web like mine, or do something different.

Students pass off their mallets to another student in the circle

Eventually, set up the instruments vertically so every third student (or so) has an instrument in front of them.

Repeat the activity. Add in playing position and rest position. Students at the instruments play the story while the rest of the class models without mallets.

When they’re done, students put down the mallets and the whole circle moves over one spot.

Step 3: Barred Instrument Improvisation

What shape did Dona Arana make as she was spinning her spider web?

The teacher plays a short fragment, then echoes the fragment vocally.

Students take turns playing a short spider web song, then pass the mallets to someone who echoes.

Doña Araña Feedback

Doña Araña: This activity is.... Too advanced for my students Just right! Too simple for my students Comment: Thank you!“Come Back, Ben”

These activities are framed around the book, “Come Back, Ben” by Ann Hassett and John Hassett.

Using a curricular lens, we’ll narrow in our melodic focus to sol mi, and sol mi la patterns.

“Come Back, Ben” Overview

Read the story

Movement and vocal exploration

Mallet exploration

Barred instrument exploration

Sing, move, and play the story

Step One: Read the Story

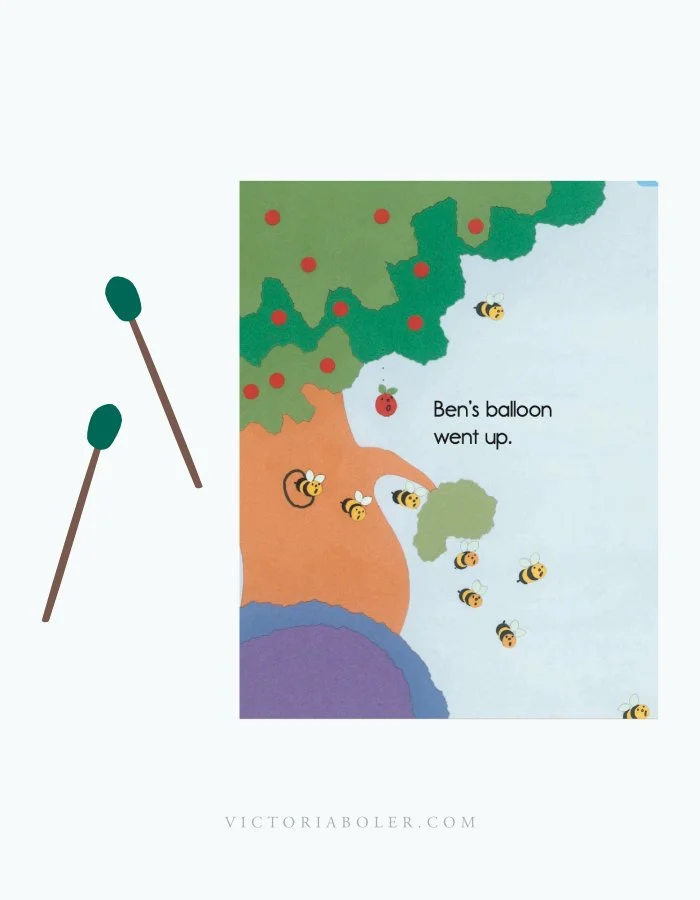

This is a delightful book about a boy who leaves his house on a balloon. The text is simple, but imaginative and playful.

In this step, we’ll read the story to students.

Step Two: Movement and Vocal Exploration

In the next reading, students find an empty space in the classroom to sit and listen to the story.

We’ll create our own illustrations of the story through movement and vocalization. Students follow the teacher’s cue to show their ideas, while staying in their spots.

The teacher reads the story again, and prompts students to use vocal and movement exploration throughout the book:

“Ben’s balloon went up” - the teacher makes a vocalization that goes up on a neutral syllable, and motions for students to echo the vocalization. Students move up as they echo

“Come back, Ben” - the teacher sings on a s m l s m pattern, and motions for students to echo

Bees - Choose one bee on the page to illustrate with your voice. Make gentle buzzing bee sounds as you trace the bee’s pathway in the air

Tree - Choose an apple from the tree. With your voice, make the apple gently fall from the tree, then roll down the hill. Staying in your personal space, show what that looks like by moving high to low as you vocalize

Kite - Trace the pathway of the kite’s string. Find a way to show that wiggly shape by lying on the ground in your own personal space.

Hill - Make your voice start at the bottom of the hill and climb up, then start at the top of the hill and climb down

Rainbow - Choose one color of the rainbow to slide down with your voice

Stars - Make twinkling star sounds with your voice while you twinkle your fingers in the air

Moon rocks - Make gentle rock sounds with your voice. Could you make gentle rock sounds by clicking your fingernails together? Tapping the floor? Scraping your shoe?

Step Three: Mallet exploration

Let’s transfer the vocal and movement exploration to mallets.

As a class, we’ll explore how the mallets can help show the story using a few selected pages from the book.

Demonstrate how to hold the mallets.

Seated in a circle, a few students at a time use their balloons (mallets) to help illustrate the text as the rest of the class continues to vocalize and move.

Students with mallets pass them to the person next to them.

Step Four: Barred Instrument Exploration

Look at the image of the hill. Notice that the high side of the hill is narrow. The low side of the hill is wide. This matches our instrument!

Hold the instrument up and demonstrate the high side and the low side. Notice that whichever way the instrument is placed (horizontally, vertically, upside down, etc.) the high side is always the narrow part of the hill, and the low side is always the wide side of the hill.

Place barred instruments vertically in the middle of the circle. Students sit behind the instrument in a row of three.

Each player in the row takes a turn making their balloon mallets gently move up the instrument, then back down, when the teacher prompts.

“Ben’s balloon went up…” Students play from low to high as the rest of the class vocalizes and moves in place

“Ben’s balloon went down… “ Students at the instrument play from high to low as the rest of the class vocalizes and moves in place

“Ben’s balloon floated right in the middle of the air…” Students play in the middle of the instrument as the rest of the class vocalizes and moves in place.

Students with the mallets pass them to the person behind them, then move to the back of the line.

Repeat until all students have had a chance to play

Step Five: Singing and playing the story

Place instruments horizontally in a circle. Students sit behind the instruments in a group of two or three.

As the teacher reads the story, the students behind the instrument continue to vocalize and move in place.

Students holding the mallets play their vocalization on the barred instrument.

“What would it sound like if you were a tiny bee buzzing gently on your instrument?” “What would you sound like if your mallets were gentle twinkling stars?” “How could you gently slide down the rainbow?”

Periodically, prompt students to hand their mallets to the person behind them and move to the back of the line.

“Come Back, “Ben” Feedback

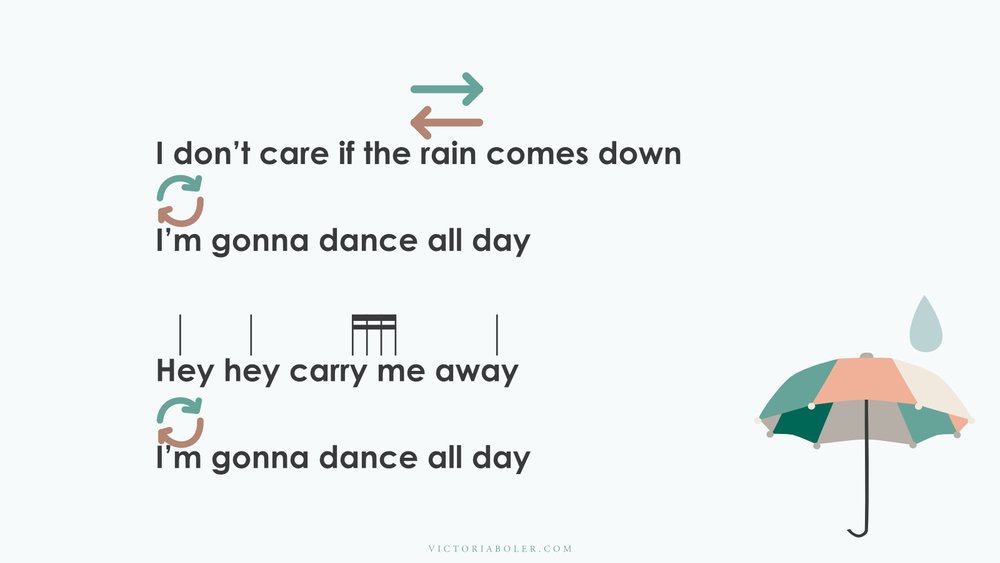

This activity is... Too advanced for my students Just right! Too simple for my students Comment Thank you!I Don’t Care if the Rain Comes Down

This activity has been adapted from the takadimi concept plan in the 2023 - 2024 Older Beginners Planning Binder.

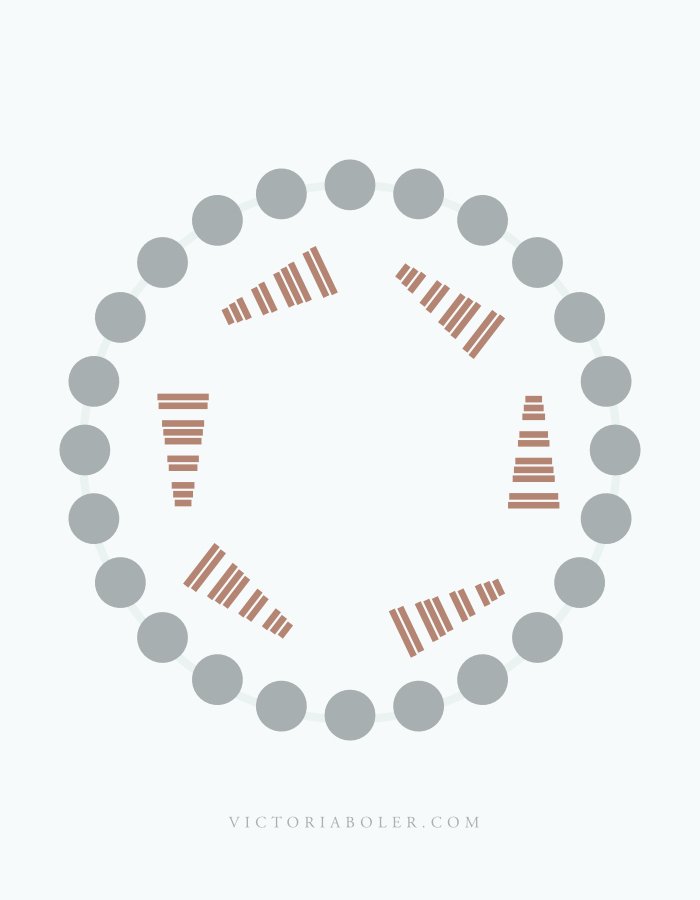

“I Don’t Care if the Rain Comes Down” Overview

Circle Dance

Body Percussion Improvisation

Barred Instrument Exploration

Barred Instrument Improvisation

Barred Instrument Rondo

Step One: Circle Dance

I developed this circle dance for upper elementary students. With scaffolding, it’s an absolute blast! Especially for students who are new to this type of movement, take the time to work up to the full routine at tempo over several interactions.

Formation: Two concentric circles, students facing a partner

“I don’t care if the rain comes down” - both circles step to the right (face a new partner) the first time. The second time we sing that phrase in the song, step to the left.

“I’m gonna dance all day” - switch places with partner

“Hey hey carry me away” - play the rhythm of the words with snap, clap, pat pat pat pat clap

Introducing the Song:

Seated, the teacher sings and students pat a steady beat. Play body percussion to the rhythm of the words of “hey hey carry me away.”

How many times do we sing and play “hey hey carry me away”? (2)

Students sing and play that section of the song instead of the teacher.

Gradually, release more of the song as students’ responsibility

Scaffolding the dance:

Sing the song standing in a circle. Continue to play the rhythm of the words of “hey hey carry me away.”

Imagine an invisible partner is standing in front of you. The teacher demonstrates switching places with an invisible partner at “I’m gonna dance all day,” then playing the rhythm of “Hey hey carry me away” on body percussion.

All together in a single circle, students practice switching places with an invisible partner, and playing “Hey hey carry me away.” When students switch places with their invisible partner, the whole circle will be back-to-back instead of facing forward.

Students find a partner in a scatter formation and practice on their own

One partner from each group moves to create a single circle. The other partner stands in front of them, creating a double circle.

Add a step to the right and to the left at “I don’t care if the rain comes down”

I find it helpful to change the words of the song “I don’t care if I step to the right” and “I don’t care if I step to the left”

Do a slow walkthrough, then add the song

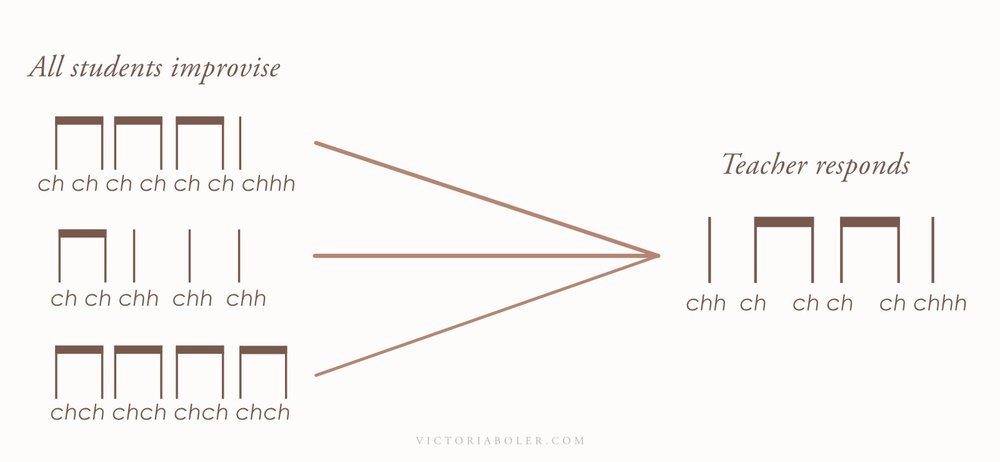

Step Two: Body percussion improvisation

As a B section, add an improvisation invitation.

Students speak “hey hey carry me away” and the teacher models improvising four beats on body percussion. Repeat three more times.

The teacher speaks “hey hey carry me away” and students improvise four beats of body percussion.

Step Three: Barred Instrument Exploration

Now we move to playing barred instruments!

The teacher shows the high and low side of the instrument, like the instrument is a mountain, with the high narrow side at the top and the low wide side at the bottom. Turn the instrument in several different positions to demonstrate that the sides are always the same.

Seated in pairs at barred instruments set up in C pentatonic, students explore gentle raindrop sounds with their fingertips. As students play, the teacher prompts different images….

What does it sound like for the raindrops to gently fall from high to low? What does it sound like for the raindrops to fall low to high? What if someone splashed in a puddle in the middle of the instrument? What if someone slipped?

Eventually transition to bouncing mallets gently instead of fingertips. As students play, encourage them to verbalize their improvisation choices and explain their thinking to their neighbor.

Step Four: Barred Instrument Improvisation

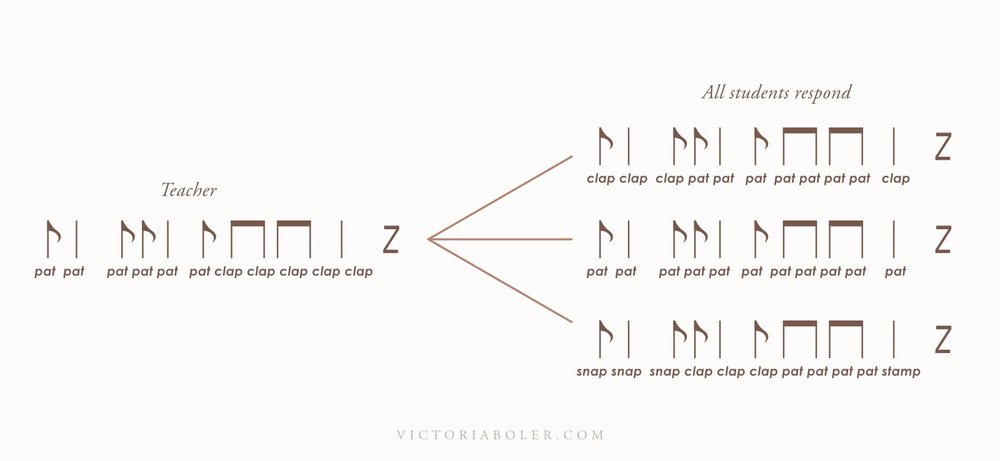

Next, we’ll ask students to improvise four beats in call-and-response, linking our improvisations back to the body percussion in step two.

Recall the body percussion improvisation from earlier.

Students speak and play body percussion to “Hey hey carry me away,” and the teacher models improvising a four-beat rhythm on one bar of the instrument. Repeat three more times.

Switch jobs. The teacher speaks and plays body percussion to “Hey hey carry me away” and students improvise four beats on a single bar. Repeat three more times.

The teacher models improvising a melody by moving the mallets around the instrument

The teacher speaks “Hey hey carry me away” and students improvise a four-beat melody on their instrument.

At the end of the activity, students turn to their partner and discuss what the activity was like for them - what is it like to make up your own rhythm and your own melody?

Step Five: Barred Instrument Rondo

In this rondo, half the class sings and moves to the circle dance. Half the class sings and plays barred instruments.

A section - All students sing the song. Players at barred instruments play a bordun and sing while players in the circle dance and sing

B, C, D, E sections - Students in the circle speak and play “Hey hey carry me away.” Players at the instruments improvise a four-beat melody while their partner improvises four beats with body percussion.

“I Don’t Care if the Rain Comes Down” Feedback

This activity is... Too advanced for my students Just right! Too simple for my students Comment Thank you!Barred Instrument Exploration in Elementary General Music

Today we’ve looked at several pathways for exploring barred instruments in elementary general music.

In these activities we can prioritize a tone of respect and playfulness. With a fingerplay with lower elementary, a book with middle elementary, and a circle dance with upper elementary, we have examples of the many avenues we can take to creatively explore these instruments.

28 March 2024, 10:26 am -

- Doña Araña: Vocal Exploration, Creative Movement, & a Chasing Game

There are some gems in our repertoire collection we can use over and over, with several grades to highlight different musical concepts. Dona Arana is one of those for me.

Today we’ll look at Dona Arana in three different contexts: Kinder and 1st, 2nd and 3rd, and older beginners.

-

JUMP TO ACTIVITIES

Dona Arana: THe Song

This is a delightful Hispanic fingerplay!

Because of the nature of how folk music spreads, and because of the prominence of the Spanish language and culture around the globe, it can sometimes be difficult to trace the exact people from whom a song originates. For that reason, the source notes this song as “traditional.”

Translation:

Dona Arana went for a walk

She spun her web and began to climb up

Along came a wind storm that caused her to dance

Along came the rain that made her come down

Concept-Based Lesson Planning

When we lesson plan from a concept-based lens, each activity is threaded together over a series of lessons.

When the activity is over, there is a logical and artistic next step. The next lesson plan is a continuation - at a deeper level - of the same concept.

A concept-based approach is a central part of the process inside The Planning Binder.

Learn more in these podcast episodes…

>>> Organizing the Music Lesson Plan: Concepts vs Activities

>>> Nesting Concepts for Active Music-Making and Active Meaning-Making

Vocal Exploration: Kindergarten & 1st grade

This activity is so simple, and so fun!

I shared a variation of the activity on this episode of Teaching Music Tomorrow.

These activities would take place over several lessons, and each interaction would be somewhere between 3 and 5 minutes long.

VOCAL EXPLORATION Overview

Introduce the song with the fingerplay

Echo vocal improvisations at the end of the song

Tell the story with vocal improvisation

Vocal Exploration Process

1) Introducing the Song

To introduce the song, we’ll sit on the floor in a circle with students, and mime out the actions of the song.

Dona Arana se fue a pasear - Our hands walk out in front of us, like a spider going for a walk

Hizo un hilo y se puso a trepar - Our hands spin up in front of us, like a spider climbing up a thread

Vino el viento la hizo bailar - Our hands dance around at the top of the thread

Vino la tormenta la hizo bajar - Our hands come back down

That’s it!

Students don’t sing at this point, they only copy our motions with simultaneous imitation.

2) Vocal Exploration

At the end of the song, the teacher sings a vocalization of Dona Arana’s thread, and students echo.

There are so many vocal shapes we could make! Did Dona Arana move from high to low?

What about low to high?

What if she made her thread loop around and around?

What if she was jumping on the thread?

3) Singing the Story

After a while, we might refine our vocal explorations to create an illustration of the story.

Could we paint the story with our voices by moving them high and low, and using different combinations of long and short?

At the beginning of the song, Dona Arana goes for a walk. What could that sound like?

What could it sound like for her to spin her web and climb up?

There was a part of the song where she was dancing at the top. What could that sound like?

What could it sound like for her to go back down the thread?

In this activity, we might choose that we want students to create their vocalizations of the whole story.

Alternatively, if we want to give a few more parameters, we can have students echo our vocalizations for the walking, climbing up, and coming down parts of the story (lines 1, 2, and 4). When Dona Arana dances at the top of the thread in the third subphrase, students can create their own dancing vocalizations.

We Sang the song. Now What?

After we sing the song and tell the story with our voices, what variations could we do? How could we extend this activity?

With a specific focus on high and low, and vocal improvisation, there are many possibilities for extensions!

At the end of the song, the teacher does a vocal improvisation and students choose if they’ll echo the teacher or do something different.

The teacher shares a vocal improvisation, and one student responds with an echo or improvisation

One student does their own vocal exploration idea, and the teacher improvises something different

One student does their own vocal exploration idea, and the whole class responds with an improvisation

One student does their own vocal exploration idea, and one other student answers with an improvisation.

Transfer vocal improvisations to barred instruments.

Creative Movement:

2nd & 3rd GradesI spoke about this song in this podcast episode about planning 2nd and 3rd Grade music, and again in this episode about what we can do when students sing a song inaccurately.

From a musical concept lens, our melodic concept is mi re do.

Even though we’re doing a creative movement activity, we’ll keep the focus on the pitch relationships of high, middle, and low.

CREATIVE MOVeMENT OVERVIEW

Trace melodic contour

Students create spider webs in self-space

Students create spider webs by connecting with a partner

Creative Movement Process

1) Introducing the song

We’ll introduce the song by asking students to listen to it several times, both as they’re stationary and as they move in open space. If you’re interested, you can listen to a podcast episode about open space here.

The teacher sings and uses spider fingers to trace the melodic contour. Students copy the motions

Students make a spider web as they move around in open space

2) Creative Movement: Connections

As a B section, let’s create some spider webs with our bodies. We’ll start the process with some open-ended creative movements. Then eventually we’ll ask students to think about a high, middle, and low spider web they can create.

Creating high, middle, and low spider webs to connect to mi re do patterns later is a nice example of physical preparation, which you can read about here.

How could you make a spider web with your body? Think about all the different connection points a spider web has. Think about how interwoven and interconnected it is.

Could you stick your arms out in front of you and connect your fingers together? …. Could you curl over to the side so your hand is touching your shoe while your other hand goes through the circle you just made with your arm? ….. Could you sit down and put your feet together and fold over your legs?

With a set of finger cymbals, or another bright instrument, the teacher signals for students to change to three different spider webs as a B section.

During the A section, students continue to move in open space with their spider web melodic contour.

When students are ready, we can refine their B section movements by asking them to choose a high spider web shape, a middle spider web shape, and a low spider web shape.

3) Creative movement with a partner

When they’re ready for the next step, ask students to find a way to connect with a partner, and create new versions of their spider web shapes.

How could you find a safe way to connect your spiderweb shape with someone else’s? Could you create a connected shape on a high level? On a low level? On a middle level?

Students have a few moments to collaborate, then we put it with the song.

During the A section, students walk around in open space spinning their spider webs to the melodic contour. By the end of the song, they should be with their partner.

As the B section, students show their high, middle, and low spider web shapes with their partner, following the teacher’s finger cymbal signals and vocal cues.

We did the activity. Now what?

What happens after we sing the song and do the movement activity? How does this creative movement prompt move us to other musical and educational experiences?

This is the beauty of planning from a concept-focus lens. Every activity we do builds, grows, and connects to another experience!

There are many extensions from here when we look at this activity as a starting place for mi re do in 2nd and 3rd grade.

Inner Hearing: Students can inner hear the melody as they move around the room in open space

Matching the Melody: The teacher draws two spider web melodic contour shapes. One matches the melody of the song, the other doesn’t. Students figure out which one is the visual representation.

Singing on Solfege: Students can sing the melody on solfege with hand signs

Barred Instrument Exploration: For students new to the barred instruments (or as review), they can explore how to play Dona Arana’s story on the bars

Playing by Ear: When students have analyzed mi re do in this melody, they can figure out how to play the melody by ear with a partner

CHASING GAME:

OLDER BEGINNERSEverything here is from the 2023 - 2024 Planning Binder.

Like the 2nd and 3rd grade activities, this focus is still on mi re do. You’ll see that in the introduction of the song, and then again in the extensions we use later.

With older beginners especially, we have an opportunity to pair competitive play with musical skill-development. Traditionally in children’s musical culture, singing facilitates cooperative and competitive games, and is an important part of learning social interaction. This is one of the ways we can increase overall musical participation, and develop “analog” social skills in the parameters of the music room. Even though this game is an addition, it is in the spirit of play-based interactions that are consistent with children’s singing culture across many musical traditions.

CHASING GAME OVERVIEW

Introduce the song with body percussion

Scaffold game with a single circle

Play game with a double circle

Chasing Game Process

1) INTRODUCING THE SONG with Body pErcussion

Our song introduction highlights mi re do through body percussion. We’re also including some opportunities for student choice as students learn the song.

The main thing to emphasize is that the body percussion pattern students have been playing matches the melodic contour of the song - when our melody goes up, our body percussion goes up. When our melody goes down, our body percussion goes down.

The teacher demonstrates a body percussion pattern, and all students join in when they can.

When students have the body percussion pattern down (or mostly down), the teacher adds the song. Students continue following the pattern as they listen.

The teacher displays questions on the board and students choose a question to answer in their heads. Repeat the activity, with students playing body percussion and the teacher singing the song.

After a few more rounds, students share what they noticed.

Eventually students have heard the song multiple times, and we can teach it by rote. Students sing the first prase, the teacher sings the rest. Gradually over time, we’ll release more phrases to students for them to sing instead of us.

2) Scaffold the Game

Eventually this game is a double-circle chasing game, which I pulled from another folk song. This game is not in the original source.

Students sing the song and walk in a circle (spider web). Switch directions at each 8-beat phrase.

Students create a double spiderweb by facing a partner, so there is an inside circle and an outside circle.

Repeat the activity, with the inside circle and the outside circle moving in opposite directions. Continue to change directions at each phrase.

Add chasing game: One student is the spider. The spider stands outside the circles. One student is the fly. The fly stands in the middle of the circles.

At the end of the song, the fly tries to get out of the circles, and away from the spider. The spider tries to tag the fly on the shoulder. The whole class counts to ten as the spider chases the fly.

3) CHASING GAME

After students have played the game and they’re ready to move on, we can point out that the game isn’t quite tricky enough. The spider can get out anywhere! What could we do to make this game even more challenging?

All students in find a way to connect (take hands, link elbows, link pinkies, etc.).

The teacher chooses a pair of students in each circle to raise their hands at the end of the song, creating an opening through which the spider and fly can move. The spider and fly can only enter and exit the circle through those openings.

But wait I just thought of an idea……

From the single circle, students move to stand in front of a partner. This creates an inside circle and an outside circle.

The inside circle connects with each other and the outside circle connects with each other. The teacher chooses a pair of students from each circle to raise their hands at the end of the song. Now, the spider and fly can only move in and out of the web through the raised hands.

We Played the Game. Now What?

What’s next?

Because we’re using this with the lens of a musical concept, and not just a fun activity (even though the activity is fun!) we can do a lot of extensions with this song.

Inside The Planning Binder we extended this song to work on do re mi and mi re do patterns.

Physical Prep: Students play the body percussion pattern with a partner

Visual Prep: Students help the teacher drag icons to show the melodic contour of the song

Present: Students establish a classroom vocabulary for the high, middle, and low sounds.

Read: Students read the melody on the board with solfege hand signs

Play: Students figure out where mi re do would live on the barred instruments

Arrange: Students use rhythmic building blocks to arrange a rhythm, then add a mi re do melody to it

Finding New Activities or Threading Musical Concepts?

When we lesson plan, it can be so helpful to look at activities through a concept lens!

What is the purpose of the activity? Where does it lead? How does this activity help us build skills and understandings over time?

Thinking about a conceptual focus can help us extend the fun of songs like Dona Arana across many different lessons, throughout many different grades.

17 February 2024, 8:03 pm -

- Kindergarten Music songs, games, & activities

Our repertoire in Kindergarten serves multiple purposes at the same time.

From a musical standpoint, these songs and rhymes form the basis for all the other musical work we’ll do in later years. Musical expectations about things like phrasing, tonality, meter, and form are constructed through active musical experiences in Kindergarten.

But perhaps more importantly, this is also where we learn crucial skills about how to interact with each other in a group setting. What is it like to make music in a collaborative, collective ensemble? What will the overall tone of music class be?

Ideally, in addition to building music foundations, we’re also building a love for music class, a joy from being together, and the capacity to engage with many different types of musics on many different levels.

Teaching Music Tomorrow: Kindergarten Music Series

In the new Kindergarten Music series on Teaching Music Tomorrow, Anne Mileski and I are talking about active Kindergarten experiences for developing musicianship skills in a play-based way.

Click here to listen and learn more.

Action Song: All Around the Brickyard

What a great action song for entering the classroom, or any time throughout the lesson!

This song has been well-loved across many places in America, but was collected in Illinois as a circle dance (McIntosh, 1957).

Song Activity:

In the classroom today, it’s more commonly sung as a follow-the-leader, action game in which students suggest movements to replace the text.

For example, “I’m gonna jump it and a jump it,” “I’m gonna wiggle it and a wiggle it,” etc.

Consider starting with the teacher as the line leader, leading the class around the room, and calling out different movements with each iteration. After a few rounds students can suggest their own motions, and eventually be the line leader instead of the teacher.

Ball-Bouncing Game: Bounce High Bounce Low

This is a Kindergarten classic!

It’s a great game to use at the beginning of the year, or after a break, especially when learning names.

Singing Game Directions:

To play the game, students stand in a circle with one student in the middle. That student in the middle bounces a ball on the strong beats of the song as the whole class sings. Instead of “Shilo,” the class sings the name of another student in the circle. The person in the middle bounces the ball to the chosen student and the two switch places. Repeat the activity with different student names each time.

To save time with choosing which student’s name the class will sing in the next iteration of the song, I have also modified this game to have a solo singing component. The whole class sings the first four beats (“bounce high bounce low”) and the student in the middle sings “bounce the ball to __(student name)___.”

Circle Game: Old Bald Eagle

A classic play party, this singing game has been re-imagined for young music students in a classroom setting.

In an interview, Jean Ritchie (1957) commented that Old Bald Eagle was often the last song they would sing at their “singing plays” before it was time to go home. This can make it another great song to use at the end of class, like “Caballito Blanco.”

Singing Game Directions:

Students create a circle with one student on the inside. That student walks around the inside of the circle as the class sings the song. At the end, the student in the middle chooses the student they are standing next to, and both students walk around the middle of the circle as the class sings “two bald eagles sail around.”

Cumulative Song: Juanito Quando Baila

How does young Juan like to dance? He dances with his feet, his hands, his fingers, his elbow…. Just like this!

This Spanish song has been loved by many children across many Spanish-speaking countries, making it difficult to pinpoint an exact location for its origin. Kindergartners can add themselves to the collection of children across the world who love singing and moving to this Spanish song!

additional Verses

(2) Con el pie pie pie (foot)

(3) Con la rodilla dilla dilla (knee)

(4) Con la cadera dera dera (hip)

(5) Con la mano mano mano (hand)

(6) Con el codo codo codo (elbow)

(7) Con el hombro hombro hombro (shoulder)

(8) Con la cabeza eza eza (head)

Song Activity:

Sing the song and dance with each new addition to the text.

This is a cumulative song. Each time through, add on one more body part to dance with!

Echo Singing GAME: Charlie Over the Ocean

By the time this singing game was recorded in its current version, it was no longer associated with its original social and political connotations. Like other mentions of Charles Edward Stewart in Scottish songs like “Over the River to Charlie,” Scottish songs with Jacobite references eventually became encompassed into play parties, then in children’s singing games, and transitioned into the singing games we love today.

Singing Game Directions:

Students create a circle with a leader on the outside. The leader sings the song while moving around the outside of the circle, and the rest of the class echoes. In the last line (“can’t catch me”), the leader taps the student closest to them on the shoulder. Both students run around the circle, with the student who was just tagged trying to catch the leader.

If the leader makes it back to the tagged student’s spot, the student who was tagged becomes the new leader and the game begins again. If the leader is caught, they lead the game in the next round.

You can also have students walk, or jump, or hop on one foot around the circle if running doesn’t work for your situation.

Greeting Song: Bonjour, Mes Amis

This activity is a hit at the beginning of my Kindergarten lessons! I’ve used it in other grades as well, and it’s just as delightful.

Translation

Hello, my friends, hello!

Song Activity

There isn’t a game or activity that accompanies this song, so this is one I have added.

In this activity, I ask students to imagine how they would greet a friend if they couldn’t use any words. We explore all sorts of non-verbal waves: waving two hands enthusiastically, wiggling fingers, Barbie wave, etc.

With a few student ideas at a time, the teacher signs and shows different ways to wave for each phrase. Students copy the teacher’s movements.

Another day, students choose their favorite three silent ways to wave. Practice switching between the three waves, following the teacher as they hold up 1, 2, or 3 fingers. Students sing the song and wave with their first, second, and third movement choices as the teacher directs.

Imaginative Play Song: Con Mi Martillo

What could we build with our hammer?

Translation

With my hammer, hammer, hammer,

with my hammer I hammer

Song Activity

In this activity I‘ve added to the song, my Kindergarteners love suggesting things we could make.

Students imagine what we could build, the class sings the song as we pat imaginary hammers, and then we inspect our work. Each iteration of the song, the teacher discovers we have made a mistake following the directions, and have almost finished building something else entirely. Students suggest what we built by accident, and we sing the song again.

LOCOMOTOR Pathway Song: Caballio Blanco

This is another hit in my Kindergarten lessons, and another song that doesn’t come with a standardized activity. Instead, I’ve added a movement activity to help us line up at the end of class.

Translation:

Little white pony, take me from here

Take me to my home where I was born

Song Activity

Students sing the song and walk in a circle. (My students sit in a circle, so it’s easy to stand and point our “noses and our toeses” in one direction.)

At some point, the teacher breaks away from the circle and the class continues to follow. Explore different movement pathways around the room such as zig-zag, straight, curvy, etc.) With each iteration of the song, ask students to suggest how much further the little white pony has to travel until we’re back home.

Eventually the teacher leads the line of students to the door.

Lullaby: Sulla Rulla

Sulla Rulla is one of my favorite lullabies for Kindergarten, or any age!

It’s associated with Østerdalen, a valley in southeastern Norway. The phases, “sulla rulla,” or “sulla lulla,” are calming sounds used in many Nordic lullabies. Traditional performance practice would include an elongation of consonants rather than vowels, specifically with the “ll” sound.

This song is sourced from the collection at Nordic Sounds.

Song Activity

Sing this song as you rock side to side. If you have stuffed animals in your class, have students take turns rocking them as they sing.

Move & Freeze dance: Las Estatuas de Marfil

This singing game from Mexico is such a great way to practice movement and stillness! Montoya-Stier (2008) suggested that teachers might give categories of statues for students to explore (animals, etc.).

Translation

Like the ivory statues,

one, two, three, like this

Singing Game Directions

There are several ways to play this game about ivory statues, all of which involve freezing in place at the end of the song.

For Kindergarten, a fun way to play is to move around a circle, or around the room in open space, while singing the song. One student stands at the front of the room, facing the other students. At the end, all students freeze in their favorite statue shape. If anyone moves the person at the front of the room calls their name and they are out in the next round of the game.

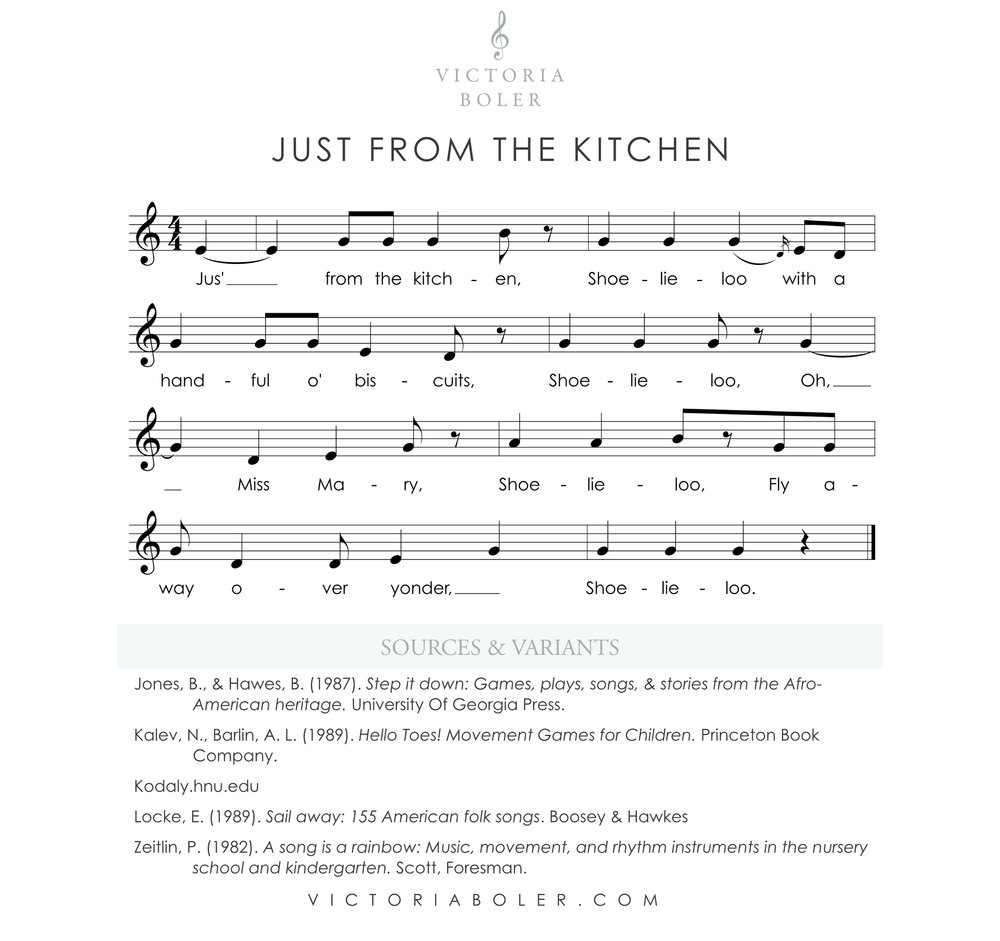

Movement Song: Just From the Kitchen

This children’s ring game was shared by the beloved singer, Bessie Jones. Bessie Jones is one of the most well-known singers from the Georgia Sea Islands, and has contributed tremendously to the field of children’s music education through her preservation and dissemination of Georgia Sea Islands culture.

The phrase, “shoo lie loo” was believed by Jones to be a joyful expression of gratitude. The song references children playing in the yard who periodically go into the kitchen and come back out with a handful of biscuits.

Singing Game Directions:

Students stand in a circle and sing the response. In the place of "Miss Mary", the lead singer sings the name of another student in the circle. That student improvises a movement as he or she travels to the opposite side of the circle.

Singing Story: Aiken Drum

The history of Aiken Drum is fascinating!

The melody I notated here is from The melody I have notated here is from Crane (1878) and Forrai (1990), but there are many more tunes associated with the name, “Aiken Drum,” and even more stories about its origin. You can find more in the “sources and variants” section of the repertoire page.

From my reading of the sources, this is a very old Scottish children’s song that was recycled into a Jacobite ballad, and like “Charlie Over the Ocean,” this song isn’t currently associated with the Jacobite cause or Charles Edward Stuart. Some other early versions include another character, Willie Wood, before Aiken Drum is introduced.

Song Activity:

In the classroom, students love changing the foods Aiken Drum was made of.

For example:

His head was made of a tomato, a tomato, a tomato...

His hair was made of spaghetti, of spaghetti, of spaghetti...

His nose was made of a strawberry, of a strawberry, of a strawberry…

Winding Game: Caracol Col Col

Winding games are delightful additions to Kindergarten music, provided every member of the group shows the self-control to keep everyone safe!

The text of this song is conducive to encouraging self-control, as students pretend to be very slow snails.

Translation

Little snail snail snail,

Take out your horns and stand in the sun

Singing Game Directions:

Students hold hands in a line, with a leader at the front. The leader moves the line in an inward circle, creating a spiral like a snail. Eventually the leader turns around and unwinds the group.

Fun & Games - where to find more

I don’t think I’ve met a person who loves Kindergarten music as much as my friend, Anne Mileski.

Anne and I collaborate on the podcast, “Teaching Music Tomorrow.” If you’re interested in more songs, games, and activities for Kindergarten music, I cannot recommend enough that you jump over to teachingmusictomorrow.com to listen to our latest podcast season about Kindergarten music!

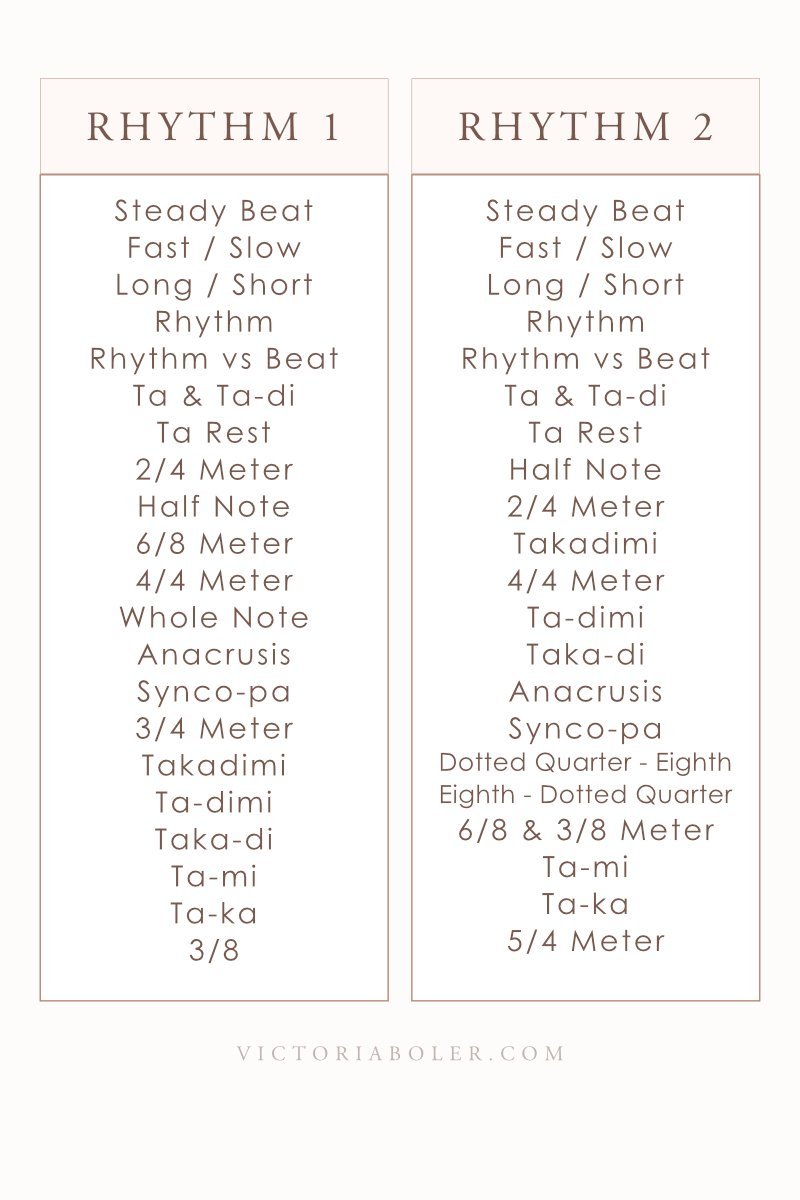

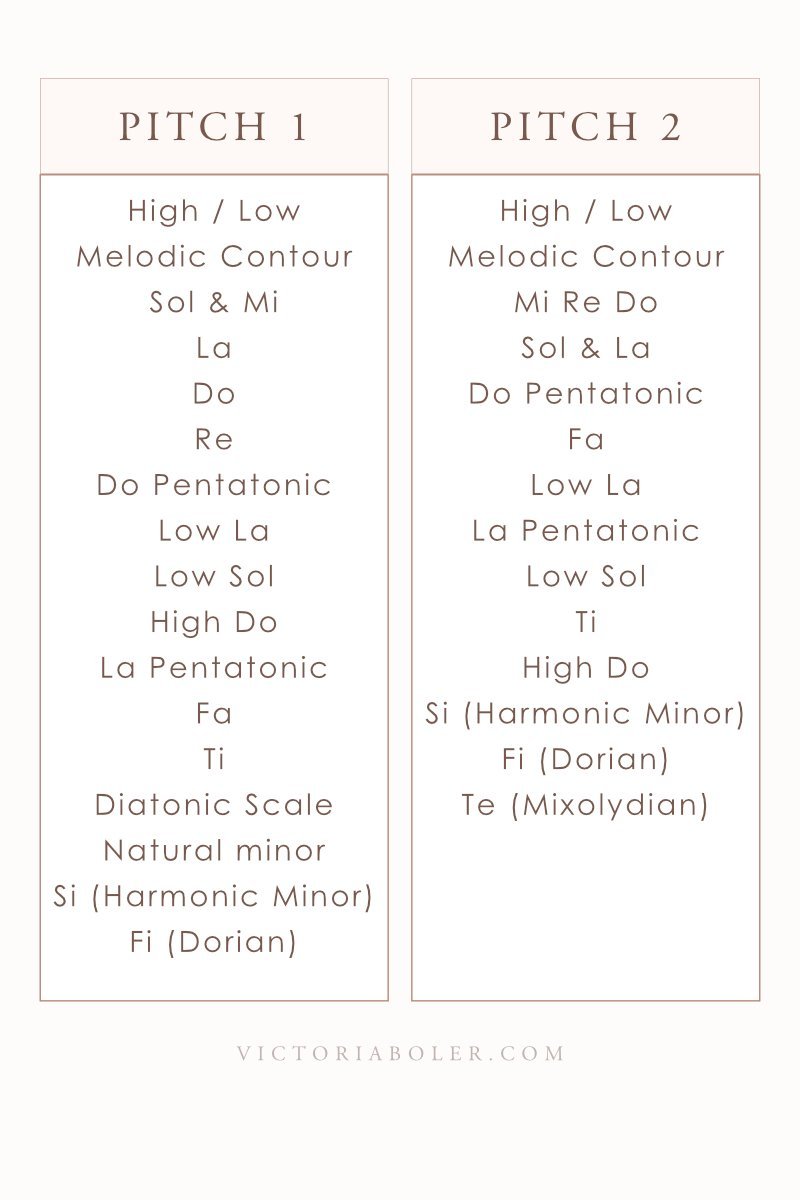

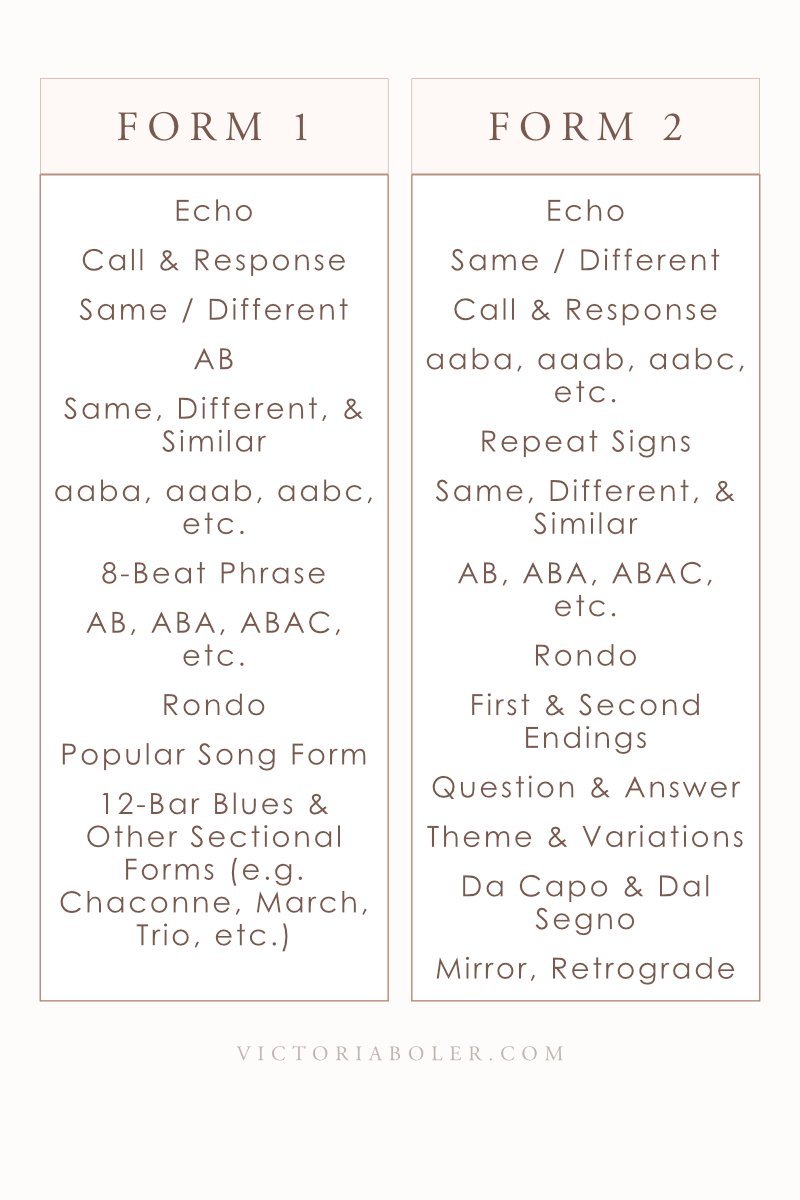

15 January 2024, 5:51 pm - Curriculum Maps for Elementary General Music

“What will I teach this year?”

“What grade does this song work for?”

“What do I do after this unit?”

These are questions we all ask in our teaching, and we can start to explore their answers with a curriculum outline, or curriculum map.

A curriculum outline is one document that can make our planning time both manageable and meaningful.

Today we’ll:

Look at a curriculum outline example

Talk about how it’s constructed

Look at other possible sequences

Think about what’s missing in the document

Let’s jump in!

Curriculum Outline

Here is an example of the curriculum outline from The Planning Binder 2023 - 2024 school year.

This is a broad look at an entire elementary music program, at each grade level.

This document is organized by musical concepts. The emphasis is on foundational musical elements that can be transferred to many different musical skills and many different areas of musical understanding.

Learn moreTwo important items to consider in the interpretation of this document have to do with the role of discipline concepts and the distinction between experiences and conscious learning.

Organized By Discipline-Specific Concepts

As we organize our curricula by concepts, we help students build understanding and transfer it to new musical situations, both inside and outside the classroom.

For example, if we teach students to understand pitch - melodic contour, intervallic relationships, etc. - and we give students tools to listen critically, analyze what they hear, and articulate their thinking, they have what they need to transfer their understanding to many different musical scenarios.

They are equipped to play a melody by ear on guitar or harmonica or metallophone. They might choose to compose their own melody and teach it to a friend or arrange it for an ensemble.

In the construction of this curriculum outline, there is a choice to lean toward transferrable musical patterns and ideas and lean away from siloed musical units.

Experiences and Conscious Vocabulary

Another thing I think is important to note about this document is that these are times when the musical ideas are highlighted and students are aligned on musical vocabulary.

These are not the only times the musical events are experienced.

For example, we can sing songs in many different modes (like these entrance songs) even if students do not consciously know the mode’s label and how to aurally identify it or write it on the five-line staff.

Read More: 3 Curriculum Outlines: Kodaly-Inspired, Orff-Inspired, and Beginning Student

Read More: Planning Ahead: Creating Your Ideal Music Curriculum

Listen: Long-Range Planning for Elementary General Music

Teaching Sequences for Elementary Music

In our conversations about what we’re going to teach in the next lesson, the “why” behind a musical sequence can sometimes be overlooked.

Even though it’s easy for all of us to get caught up in our efforts to make music with students as quickly and efficiently as possible, thinking through the purpose of a teaching sequence can be helpful as we make decisions about our own situations.

Known to the Unknown

One of the core principles we use in a spiraled curriculum is the idea of moving from the known to the unknown.

This came out of the work and followers of Pestalozzi. Educators who use this principle believe that learning does not take place in a vacuum. When students learn something new, it is because they have connected it to previously known material.

Musical knowledge and understanding are predicated on older information and experiences.

As we move from what Pestalozzi described as “from the simple to the complex,” we can help students process through and link old (known) musical patterns and vocabulary to new (unknown) musical experiences. Students can consider the aural qualities of new musical material (tonality, duration, intervals, patterns, etc.) by comparing it to the musical qualities they already know.

Sequence Options

As we put together a sequence of musical patterns, we want the information to be in a logical and artistic flow of musical ideas.

The way we get there is by choosing a sequence that has patterns organically represented in the repertoire. The role of the teacher is not to manufacture a curricular experience. Instead, it is to help students guide their ears and pull out extractable patterns.

With the criteria of a logical and artistic flow of patterns represented organically in the repertoire, there are many possible options for musical sequences! And music teachers certainly use a variety of well-thought out progressions of musical ideas in our teaching. Teachers naturally use different sequences, and even within classrooms following the same sequence, no two teachers give instruction or direct learning in exactly the same way.

Each situation is unique.

Example Sequences

Here are a few example sequences for elementary general music. Certainly, more exist in our classrooms, and even more exist in musical repertoire.

The reason to consider these examples is to illustrate that each of us can make informed decisions about our progressions based on many different factors.

A list of sources is included at the bottom of this post.

Rhythm and Pitch Sequences

Many educators choose to structure their curricula largely around rhythm and pitch.

In my opinion, this is because having aural training and common vocabulary around rhythm and pitch allows us to communicate more clearly about other musical elements.

So for example, we can describe the form of a song easier if we can describe the rhythm changes in the different sections. It’s easier for us to describe the harmonic outline of a piece if we have training and a common vocabulary to describe the contour of the bass line.

In this decision of a curriculum outline, rhythm and pitch function as pillar progressions, and do a lot of heavy lifting in the framing of other elements.

Here are a few examples - to reiterate, there are more options available than what is represented here!

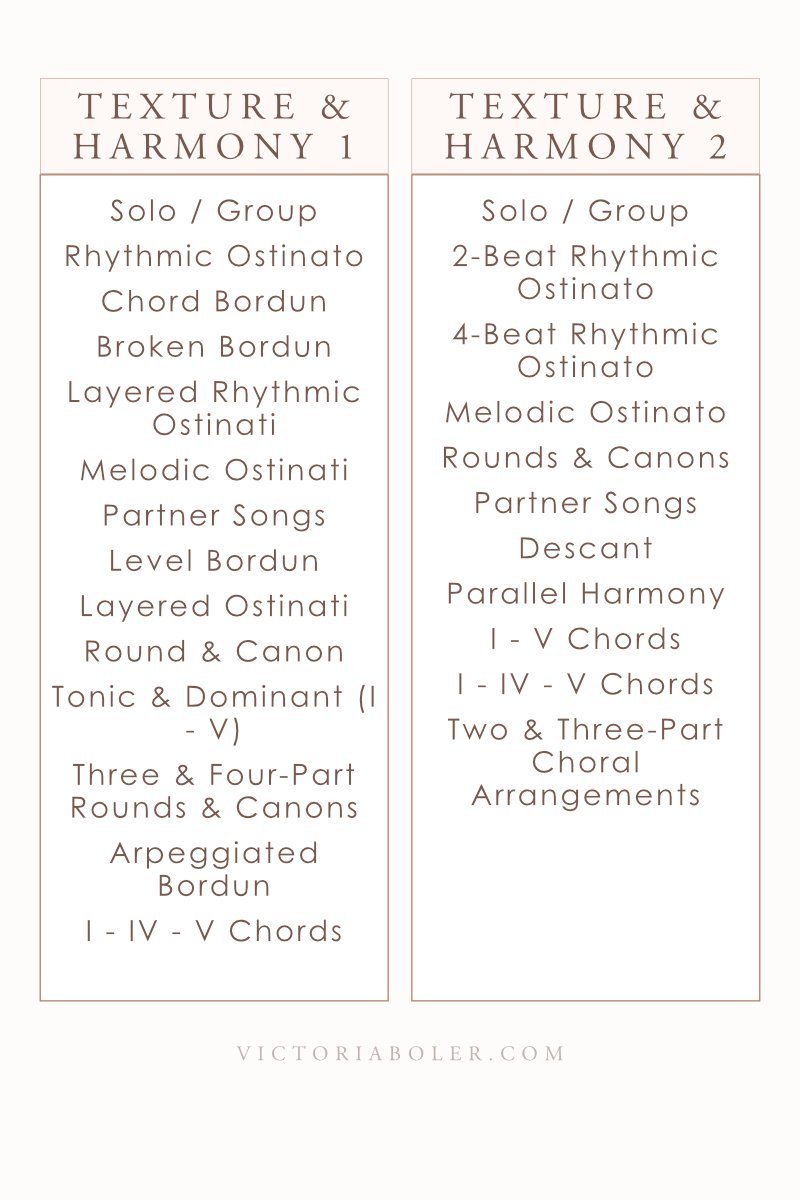

Form, Texture & Harmony

Other musical elements, such as form, texture, harmony, dynamics, etc., also arise organically from the repertoire.

However, we typically don’t see curricula grounded on these elements in the way we see them oriented around rhythm and tonal patterns.

Additionally, many of these micro-concepts arise as students are ready for them from a skills-based perspective. There is a natural physical, cognitive, and aural level readiness students work through on their way to things like arpeggiated borduns and parallel harmony.

Which One Should I Use?

Because each of these sequences is a skillfully-crafted progression of micro-concepts that are naturally represented in the repertoire, how might we go about choosing one to use?

I prefer the one we’re using inside The Planning Binder, but the good news is that rarely will we find ourselves stuck with one set of sequences we find on a website or in a textbook.

Year to year, school to school, and perhaps within a single semester, we can pivot and make adjustments based on what will work best for our students. Though consistency in the sequence overall will improve cohesive learning, we are largely free to adjust our focus based on student feedback.

Listen to Dr. Amanda Hoke talk about changing her melodic sequence in tomorrow’s podcast episode.

Considering a few options gives us a sense of the menu we have when looking for a spiraled progression of concepts for our programs.

Implications of a Sequence

Ultimately, that is one of the big implications for a teaching sequence.

The progression we choose will impact the repertoire we select.

The dance is also true in reverse: the repertoire we select will impact the sequence we choose.