Across Women's Lives

Across Women's Lives is home for PRI's collaborative radio, web and social media coverage of gender equity around the world. PRI’s The World and our partners travel across the globe to share stories of what it takes to change the status of women. We look at how initiatives that raise women's status affect their communities and countries.

- Abortion is illegal in Malta. Activists are trying to increase access.

Last September, gynecologist Isabel Stabile stood outside the Maltese Parliament with a group of activists on International Safe Abortion Day, holding signs that said: “Abortions are safe and necessary” and “My body is not a political playground.”

As they livestreamed the protest on Facebook, some activists took out a box of fake abortion pills and swallowed them.

“Malta is the only country in the whole of Europe where abortion is still illegal, under all circumstances.”

Isabel Stabile, abortion rights activist, Doctors for Choice, Malta“Malta is the only country in the whole of Europe where abortion is still illegal, under all circumstances,” said Stabile, as the camera zoomed in on her. “We are here to show you how easy and simple this process can be.”

The protest was small — and later met by a bigger crowd from anti-abortion protestors — but it signals a growing abortion rights movement in the small, predominantly Catholic island of Malta in the Mediterranean, where more than 90% of the population are against abortion, on religious grounds.

Related: Catalonia’s temporary tele-abortion services are a game-changer

Unlike Poland, where abortion is difficult to access, but still legal in cases of rape and incest, the abortion law in Malta doesn’t make any exceptions — even when the mother’s health is at risk.

As a result, an estimated 300 pregnant people travel abroad every year to seek abortion services in places like the United Kingdom and Italy, but when the COVID-19 pandemic hit in March of 2020, travel restrictions made such trips nearly impossible.

Stabile, who is part of the advocacy group Doctors for Choice, said that’s when calls to the organization shot up significantly.

“What happened at that point is that women became desperate,” Stabile said. “And it pushed us as pro-choice doctors to set up a service.”

The Family Planning Advisory Service (FPAS) was launched last August, and is run by trained volunteers providing medically-based information about reproductive health care — fertility, contraception or abortion.

Under Malta’s abortion law, doctors can face up to three years in prison for providing abortion services, so FPAS volunteers figured out a work-around: They inform callers of the travel restrictions for countries where abortion is legal and tell them about reliable nongovernmental organizations that ship abortion pills — although it is illegal to consume them on Maltese soil.

Related: In Italy, religious organizations’ ‘fetus graves’ reignite abortion debates

“We have effectively created a telemedicine service. … People are now no longer needing to travel as often.”

Isabel Stabile, abortion rights activist, Doctors for Choice, Malta“We have effectively created a telemedicine service,” Stabile said. “People are now no longer needing to travel as often.”

Stabile said that within the first six months of launching, FPAS received more than 200 calls — in a country with a population of less than 500,000 people. What’s more, the number of abortion pills ordered online from organizations like Women on Web and Women Help Women doubled from 2019 to 2020.

But taking the abortion pills Mifepristone and Misoprostol is only considered safe up until the 12th week of pregnancy. For people needing an abortion past 12 weeks, including those who have found out about a fetus abnormality, taking a pill is no longer a possibility.

For people who are more than 12 weeks pregnant, taking a pill is no longer a possibility, which often applies to pregnancies with fetal abnormalities, as well.

Mara Clarke, from the Abortion Support Network, said those are the people who continue to travel for abortions — despite the pandemic. Clarke’s organization helps fund pregnant people’s trips to the UK from countries where abortion is illegal or severely restricted.

“At the beginning of the pandemic, we really didn’t know what was going on,” Clarke said. “They were closing airports, we would book flights and they would get canceled, people were scared about traveling.”

There were nonstop hurdles: border closures, shut hotels, no child care. It was especially hard for Maltese people, who live on an island and are geographically isolated.

Related: Abortion increasingly hard to access in Turkey

Nowadays, Clarke said, traveling is somewhat easier, but mandatory PCR tests make it more expensive and constantly changing measures make it more difficult.

“Prior to COVID, the Draconian abortion laws were an inconvenience for women and pregnant people with money, and they were only a catastrophe for people without money or resources or support networks.”

Mara Clarke, Abortion Support Network“Prior to COVID, the Draconian abortion laws were an inconvenience for women and pregnant people with money, and they were only a catastrophe for people without money or resources or support networks,” Clarke said.

“But suddenly, you have a global pandemic, and literally everybody understands what it means to live in a country with really a bad abortion law.”

According to the UK’s National Health Service, the number of Maltese people who traveled there for abortions decreased by two-thirds from 2019, when 58 abortions were registered, to 2020, when 20 abortions were registered.

As part of an ongoing collaboration, Clarke is now funding a helpline at Malta’s Family Planning Advisory Service.

Dr. Christopher Barbara, another member of Doctors for Choice, said the goal of FPAS is to fill the void left by the lack of a government-established family planning programs.

“We feel that people have a right to that information because, if nothing else, it’s a harm-reduction exercise.”

Dr. Christopher Barbara, Doctors for Choice, Malta“We feel that people have a right to that information because, if nothing else, it’s a harm-reduction exercise,” said Barbara. “If a woman can’t get the abortion pill safely, she’ll just end up getting them from unverified sources.”

To this day, no major political party in Malta has come out in favor of abortion rights — but some individual politicians are starting to speak up.

This May, one parliament member introduced a bill to decriminalize abortion, though it didn’t pass. President George Vella later responded to this move, saying he’d rather resign than sign a law that “involves the authorization of murder.”

Abortion is still very much taboo in Malta — and abortion rights activists who speak publicly about it often face online harassment from anti-abortion groups.

But Barbara said public discourse is starting to shift — websites like Break the Taboo, which tell the stories of people in Malta who had an abortion, are hoping to destigmatize the topic.

And Barbara said it’s working. In 2016, the morning-after pill was legalized, and in 2018, the first abortion rights group in Malta was founded.

Since then, similar organizations have emerged and local media are increasingly covering the abortion debate.

“People are starting to realize that you can personally be against abortion, but at the same time, an abortion ban is not the right way to go,” Barbara said.

This story was produced in partnership with the International Women’s Media Foundation.

The post Abortion is illegal in Malta. Activists are trying to increase access. appeared first on The World from PRX.

1 July 2021, 5:57 pm - Iron Dames: The all-female team racing to bring change to motor sports

A black and pink Ferrari coils and loops around the Mugello Circuit, just outside Florence, and guns across the finish line at 170 miles per hour. The roar of its engine echoes throughout the Tuscan countryside.

This sleek ride isn’t your typical commercial sports car, it’s a Ferrari 488 GTE — a hyper-tuned machine built for endurance racing, with a cockpit made of carbon fiber and rebar steel.

Steering behind a wheel full of buttons is 27-year-old Michelle Gatting, an ambitious pilot from Denmark.

Related: In Spain after lockdown, soccer resumes for men — but not for women

Gatting started riding go-karts at the age of 7. Today, she is the youngest member of the Iron Dames, an all-female professional racing team that competes in Grand Touring endurance racing, or GT.

“An Iron Dame is a determined, strong-willed woman who has strong goals in her life. …and who is really passionate about what she’s doing.”

Michelle Gatting, 27, Iron Dame pilot“An Iron Dame is a determined, strong-willed woman who has strong goals in her life,” Gatting said. “And who is really passionate about what she’s doing.”

Related: A #MeToo for Afghanistan’s women’s soccer: ‘It happened so many times’

Close up of an Iron Dames race car. Courtesy of Iron Dames

Close up of an Iron Dames race car. Courtesy of Iron Dames

The Iron Dames is one of just three all-female teams in the world that competes head-to-head with men.

The International Federation of the Automobile (FIA), the global governing body for motor racing, has praised them as a “sign of progress” in this male-dominated sport. Far from a marketing gimmick, the Iron Dames have already qualified for big-name races, and are hoping to change the perception of women in the sport.

Related: Women’s pro soccer made gains toward parity. Will coronavirus undo it?

“We fight, we want to win, we want to go for the podiums. … And when you do that, and you get [to] those podiums, people they don’t question anymore why you’re there.”

Michelle Gatting, 27, Iron Dame pilot“We fight, we want to win, we want to go for the podiums,” said Gatting, referring to where winners stand to receive first, second or third place. “And when you do that, and you get [to] those podiums, people they don’t question anymore why you’re there,” she said.

Michelle Gatting sits behind the wheel of her race car. Angelica Marin/The World

Michelle Gatting sits behind the wheel of her race car. Angelica Marin/The World

GT endurance racing is like marathon running — but for sports cars. Teams of pilots speed around twisty circuits for hours at a time, while racking up an insane amount of laps — sometimes up to 2,000 miles, depending on the race.

In 2019, the Iron Dames became the first ever, all-female lineup to begin and finish the legendary 24-hour of Le Mans —the mother of all endurance races. Teams of pilots take turns driving one car for a full day and a full night. They pause only for seconds at a time to switch tires or pilots.

Last year they finished in the top 10 at Le Mans. This year, reaching the podium — in the top three — would be the ultimate game changer.

“That would be fantastic, a dream come true,” said Deborah Mayer, Iron Dames’ founder and leader.

Mayer, a French financier, entrepreneur and pilot, founded the Iron Dames in 2018 to promote women in motor sports. “And to give the possibility to talented women to show all their capacities and skills in a quite competitive environment,” said Mayer.

As a long-time Ferrari collector, Mayer caught the speed bug racing in Ferrari tournaments. Now, she is betting big to take the Iron Dames to the top.

Motor sports is one of very few sports where the athlete’s sex doesn’t matter, said Mayer. At the end of the race, what separates a good pilot from the rest is strictly the lap time.

“It’s not a question of strength…it’s skills, it’s hard work…you have to improve and work on your technique. … You have to have the right strategy, and, above all, you have to work as a team.”

Deborah Mayer, Iron Dames leader“It’s not a question of strength…it’s skills, it’s hard work…you have to improve and work on your technique,” said Mayer. “You have to have the right strategy, and, above all, you have to work as a team,” she said.

Iron Dames pose for a portrait at Mugello. Angelica Marin/The World

Iron Dames pose for a portrait at Mugello. Angelica Marin/The World

Mayer describes teamwork as “working at it, till the mayonnaise thickens.” Professional racing teams require million-dollar cars and a traveling crew of coaches, mechanics, engineers, and other staff working up to 24 hours at a time with the pilots.

Together with Mayer and Gatting, Manuela Gostner from Italy, and Rahel Frey from Switzerland, make up the original Iron Dames team.

This year, British pilot Katherine Legge also joined the all-female line-up.

Legge has done it all: NASCAR, Indy 500, Formula E and GT. She doesn’t come from a dynasty of racers — or from money. She had to fight her way into the racing circuits on her own.

“That’s why people like Deborah [Mayer] are so important, because when we get together we can do so much more,” said Legge.

Legge said one of the biggest challenges for women drivers can be getting sponsorship due to entrenched stereotypes about women in motor sports.

“Sponsors — a lot of them don’t want to see women get hurt, don’t necessarily believe that women can win.”

Katherine Legge, Iron Dame pilot“Sponsors — a lot of them don’t want to see women get hurt, don’t necessarily believe that women can win,” said Legge.

Legge broke both her legs last summer during a test drive in France. In just seven months she reached race-ready fitness. Now, she says, she has unfinished business.

“I want to go out on a high and win championships and win races, and I want to do it as part of an all-female team,” said Legge. “Because I think that the first all-female team that does that, will put a stamp on it, and then, you know, maybe I help other girls to become the next Iron Dames,” she said.

This year, the Iron Dames have 30 races to make their mark and push for that change. When women reach the podium, sponsors take notice, and new opportunities open up for more fierce girls in the game.

The post Iron Dames: The all-female team racing to bring change to motor sports appeared first on The World from PRX.

19 March 2021, 6:51 pm - How women and girls are especially at risk of hunger during the pandemic

The economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic has driven an unprecedented increase in hunger across the world, according to the United Nations’ assessment of humanitarian needs in 2021, released this week.

It says the number of people across the globe at risk of hunger is up 82% from a year ago, to an astounding 270 million. A whopping 70% of them are women and girls.

They are more likely to go without food so others in their families can eat. And, for them, hunger leads to other dangers: Girls are being forced into child marriages; women are resorting to transactional sex, and human trafficking is on the rise.

“There has been a surge in kidnappings. A lot of young girls have gone missing. It’s heartbreaking and scary.”

Ashlee Burnett, Feminitt“There has been a surge in kidnappings. A lot of young girls have gone missing,” said Ashlee Burnett, 23, an advocate and poet in Trinidad and Tobago. “It’s heartbreaking and scary.”

Organizations like Burnett’s nonprofit, Feminitt, are stepping in to help women while the international humanitarian community struggles to raise funds to respond. Burnett’s six-person staff worked long hours without pay to create online resources that connect women facing abuse with help. Burnett said they may not be reaching huge numbers of women, but it’s more than the government is doing.

“They haven’t put things in place, like proper protective policies, even now, to protect women and children,” she said. “There’s a recovery committee that seeks to only focus only on the economy, but not understanding that we have to have these laws revamped, we have to take care of our most vulnerable.”

‘They are not protected’

Governments and humanitarian groups are not responding forcefully enough to COVID-19’s disproportionate impact on women and girls in part because they lack representation “at the decision-making table,” said Hilary Mathews at CARE, an international nonprofit focused on gender issues.

Mathews said CARE reviewed 73 COVID-19 reports by UN agencies and the World Bank — and almost half of them failed to mention women’s and girls’ specific needs. CARE also looked at national committees set up by countries to respond to the fallout from COVID-19. They found that 74% of those committees had fewer than one-third women members, and only one group was “fully equal,” she said.

Another bigger problem is money. The Norwegian Refugee Council just released a report that said international donors only provide a fourth of the funding necessary to protect marginalized people worldwide, even as gender-based violence spirals out of control.

“Tens of million [sic] of the most vulnerable on this planet are under attack from men with guns and power and they are alone. They are not protected.”

Jan Egeland, Norwegian Refugee CouncilThe council’s secretary-general, Jan Egeland, said at a Dec. 1 online meeting of global humanitarian groups, “Tens of million [sic] of the most vulnerable on this planet are under attack from men with guns and power and they are alone,” adding, “They are not protected.”

At that same meeting, William Chemaly, who coordinates international humanitarian assistance, said that the most effective response would be to funnel resources to local organizations with the most access to people who need help, but the challenges are plenty.

“Those who have the best possible access on the ground to deliver assistance have the worst access to resources,” he said. “We need to change that.”

Related: At the UN review of US human rights, the Trump administration gets an earful

Communities mobilizing

Some local actors aren’t waiting for international help. In Queens, New York, 26-year-old Aatish Gurung heard from undocumented friends struggling to buy groceries, who couldn’t afford menstrual products.

“What I thought was, ‘Someone has to do something about this,’” he said. “And my parents — they always tell me, ‘If you want something, go for it’ — like not to wait for someone else to do it for you.”

So, he reached out to the global nonprofit Period; within two weeks, it sent him bulk packages of tampons and sanitary napkins. Gurung used his network as a long-time advocate, and with the help of volunteers, distributed the products to hundreds of Bhutanese, Nepali and Tibetan immigrants.

“It was really amazing to see people coming together even during these hard times,” Gurung said.

In Nepal, 27-year-old Rukumani Tripathi had just graduated as part of the Midwifery Society of Nepal’s first class of midwives when the lockdown hit. She and fellow graduates handed out their personal phone numbers to pregnant women who couldn’t go to the hospital.

Eventually, donors helped establish a 24-hour toll-free number that provides free counseling for hundreds of Nepali women.

“We never thought we could make this big impact in the society [sic] and we could help women even though we are at home.”

Rukumani Tripathi, Midwifery Society of Nepal graduate“We never thought we could make this big impact in the society [sic] and we could help women even though we are at home,” Tripathi said.

Related: Bars for queer and transgender women are disappearing worldwide. Will they survive the pandemic?

And in Romania, 18-year-old Sofia Scarlat’s gender equality nonprofit, Girl Up Romania, saw a surge of messages from women and girls asking for help dealing with online revenge pornography.

“Everybody moved into the online world and all the violence that women and girls dealt with face to face moved online with us,” she said.

Scarlat said there’s not much help from lawmakers in Romania to address online harassment, and police don’t pursue justice for victims. So, her team worked with journalists to uncover a network of thousands of people online sharing revenge pornography of Romanian women and girls. As a result, Scarlat said she became a target of harassment and threats.

“It’s really remarkable and very saddening that around the world, so many young advocates are having to risk their safety in order to do the jobs of people who are literally being paid to carry out these tasks,” she said.

Scarlat doesn’t regret her activism, though — she said when women and girls face hunger and violence and aren’t getting the help they need, it’s the community’s responsibility to do something about it.

The post How women and girls are especially at risk of hunger during the pandemic appeared first on The World from PRX.

4 December 2020, 5:55 pm - Abortion increasingly hard to access in Turkey

When Sevilay, a 38-year-old, stay-at-home mom in Istanbul, learned she was pregnant with a third child, she agonized over what to do.

“I became very upset when I learned about my pregnancy. I wondered whether I could do it or not. I was already having a hard time with two kids. There was nobody that could help me.”

Sevilay, a mother of two in Turkey who had an abortion“I became very upset when I learned about my pregnancy. I wondered whether I could do it or not. I was already having a hard time with two kids. There was nobody that could help me,” said Sevilay, who asked that her full name not be used for privacy reasons.

After thinking about it, she made the tough decision to have an abortion, something she needed permission from her husband to do, as is required by law in Turkey. She thought that would be the hardest part.

Related: In Turkey, a conservative push to remove domestic violence protections is met with an uproar

The greater challenge, though, was finding a hospital willing to perform an abortion. Private hospitals cost too much, up to $500. But public ones kept turning her away.

Turkey is one of the few majority-Muslim countries where abortion is legal, but access to them is becoming increasingly limited under the conservative government. Abortion has been legal in the country since 1983 — and wealthy women from places such as Saudi Arabia and Iran, where the procedure is banned, often turn to Turkish clinics. But it’s still deeply stigmatized in Turkey.

In the last decade, the ruling conservative AK Party and President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan have been chipping away at reproductive rights. Police have busted back-alley clinics for low-income women while many public hospitals have stopped providing abortions altogether.

In 2012, the government tried to reduce the 10-week pregnancy limit to six weeks, but feminists fought back and won. Erdoğan publicly calls abortion a crime and says women should have at least three children.

Sedef Erkmen, who authored a book on the subject, told Duvar, a Turkish news site, that the “anti-abortion practices that have been systematically implemented since 2012 turned into a de facto ban.”

Related: Turkey passes ‘draconian’ social media legislation

Public hospitals can simply refuse women access based on what the president says, not the law. So, low-income women — in many cases, Syrian refugees — turn to back-alley clinics that do the procedure illegally.

Last year, news broke that police had raided a clinic fronting as a Syrian hair salon. Three people were arrested.

Related: Expulsions, pushbacks and extraditions: Turkey’s war on dissent extends to Europe

An all-too-familiar story

Sevilay reached out to Mor Cati, a women rights group, which helped her find a public hospital to do the abortion for free. But she says that even that hospital’s staff tried to make her feel guilty, and threatened her.

“They said, ‘If you come to this hospital for another abortion, we won’t let you in,’” she said.

She had an abortion at nine weeks, one week before it becomes illegal in Turkey. Sevilay says she felt broken by the emotional toll and harsh treatment. After the abortion, she felt awful.

“I felt bad. I woke up crying. To be honest, sometimes my heart aches.”

Sevilay, a mother of two in Turkey who had an abortion“I felt bad. I woke up crying. To be honest, sometimes my heart aches,” she said.

Unfortunately, Sevilay’s story is all too common in Turkey. That’s something that Hazal Atay can attest to. She’s an outreach coordinator at Women on Web, a Dutch-based platform that helps women get access to abortions in restrictive countries.

Turkey banned Women on Web’s website in 2016. But Turkish women still find ways to contact them. Many are faced with dire circumstances.

Related: Turkey’s president formally makes Haghia Sophia a mosque

Like one 22-year-old woman in Erzurum, whose letter Atay shared with The World, in English: “I’m sure this situation is difficult for everyone, but if my family learns about the pregnancy, they won’t let me live. I know you help a lot of people, but you don’t know where I live, and you don’t know my family. You are my only hope,” the woman said in the letter, adding, “Please get back to me as soon as possible. I cannot trust anyone except you. This is a conservative city. Even if I go to the hospital … they will let my family know about it. Please help.”

Two other letters sent to them from women in Istanbul reflect the same desperation. One woman says she doesn’t have the money to get an abortion. Another has run away from a violent husband but needs his permission to abort her pregnancy.

Sevilay says she is still criticized by some of her women friends for having an abortion. But she says she just wants what is best for her family: “I am trying to set higher standards for my children. I am trying to provide them a good life … I can give birth to five children and can raise them very well, but I can’t provide them good opportunities.”

The post Abortion increasingly hard to access in Turkey appeared first on The World from PRX.

5 October 2020, 6:55 pm - Afghan women negotiating with the Taliban say they feel ‘heavy responsibility’

After almost two decades of war, representatives from the Afghan government are meeting with Taliban leaders in Doha, Qatar, to discuss a peace agreement.

Four of the 42 negotiators are women — all on the Afghan government team — and they are looking to stand up for their hard-won rights.

Related: Afghan peace talks set to start despite escalating attacks

The Taliban ruled Afghanistan in the 1990s. They instilled a sense of fear among many women. They banned them from leaving their homes without a male chaperone, restricted their education and forced them to wear burqas — the loose-fitting outfit that covers their bodies from head to toe.

The US invasion in 2001 toppled the Taliban and in the years since there has been major progress in women’s rights. Now, with the possibility of another Taliban power grab, many worry about losing those rights.

Habiba Sarabi, speaking from Doha, said she was not nervous about the meetings, but that she came to the Qatari capital with a big task.

“It’s not easy work. We feel a kind of heavy responsibility on our shoulders.”

Habiba Sarabi, Afghan negotiator in the peace talks with Taliban leaders“It’s not easy work,” she said. “We feel a kind of heavy responsibility on our shoulders.”

Related: Hundreds of prisoners missing after Afghanistan prison attack

She said back home, women are counting on her and her colleagues to safeguard what they achieved in the past two decades.

Today, women in Afghanistan can hold public office. Sarabi herself is an example of that. She was the first woman to be elected governor. She also served as the minister of women’s affairs and education.

Last week, the two sides appointed two “working groups,” which each have five members. They met to discuss procedural matters such as how to conduct meetings and what rules to follow. Ten days later, they are yet to reach a consensus on that.

“I thought the procedural matters would only take a few hours,” said Sharifa Zurmati Wardak, another representative participating in the negotiations.

Zurmati is not part of the working groups, but she said complications often arise when the negotiators bring back ideas to their teams.

“Sometimes, they don’t agree to the points that were brought up and they have to go back with new suggestions,” she said.

The slow progress shows just how complicated the negotiations are. Years of war have left the two sides weary and skeptical of one another.

Related: A newborn survived an attack at a hospital in Afghanistan. Now the long road to recovery begins.

Meanwhile, back in Afghanistan, the violence continues. Just as the talks were getting underway in Doha, a local official in Zurmati’s province was shot dead.

According to Paktia’s media office, Ayub Gharwal was attacked and killed by gunmen on Sept. 19.

Zurmati got the news in Doha.

“There is no question: We want an immediate ceasefire. People of Afghanistan are tired of the bloodshed. It’s time to stop the killing.”

Sharifa Zurmati Wardak, Afghan negotiator in the peace talks with Taliban leaders“There is no question: We want an immediate ceasefire,” she said. “People of Afghanistan are tired of the bloodshed. It’s time to stop the killing.”

A ceasefire is one of the main sticking points. Taliban representatives have said they are not ready yet to agree to an immediate and permanent ceasefire.

Zurmati has been answering messages from people back in Afghanistan nonstop. They want to know how the process is shaping up.

“Every day, we ask when are we going to start talking about the real issues?” she said. “People of Afghanistan have been at war for 40 years. It’s hard, but we have to be patient.”

The post Afghan women negotiating with the Taliban say they feel ‘heavy responsibility’ appeared first on The World from PRX.

23 September 2020, 6:25 pm - RBG’s early days in Sweden shaped her fight for women’s equality

Since the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg on Friday, there has been an outpouring of recognition for her work fighting for justice in many corners of American society.

Lesser known is how a period of her life spent outside the United States influenced her views on equality for women.

In the early 1960s, Ginsburg traveled to Sweden and learned Swedish to work on a project with a Swedish legal scholar, Anders Bruzelius, on the rules of civil procedure in Europe.

Karin Maria Bruzelius is a former justice on the Supreme Court of Norway and is now at the Scandinavian Institute for Maritime Law at the University of Oslo. She’s also the daughter of Anders Bruzelius. She spoke to The World’s host Marco Werman about Ginsburg’s legacy and what she learned in Sweden.

Related: Ginsburg’s impact on women spanned age groups, backgrounds

Marco Werman: Judge Bruzelius, I’d like to start with your reaction to the news of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death. What have you been feeling?

Karin Maria Bruzelius: I’ve been feeling a lot of sadness. I had great admiration for her, and she’s played a very important part in my family’s life.

In the early 1960s, Ruth Bader Ginsburg traveled to Sweden to work on a research project with your father, Anders Bruzelius. Explain what that project was about. What were they researching?

At Columbia University, they had undertaken to present the rules on civil procedure in several European countries, and Ruth and my father were asked to undertake the Swedish part of the project. … They started the project in 1961, and they corresponded for a year while Ruth was learning Swedish in New York. They were exchanging views and opinions, and then she came with her daughter Jane…to Lund, in Sweden, where my family lived, and she stayed there for several months that year.

Do you have memories of her from that time?

My memory is of a person who was very serious, who was very eager to do the work, and who was very interested in the way we, in Sweden, arranged the way that women could work.

Interestingly, Ruth Bader Ginsburg spoke some years later and said her “eyes were opened up in Sweden.” For the first time, she saw law school classes where a quarter of the students were women. So, coming from the US, just how surprising would that have been, do you think, to a young Ruth Bader Ginsburg?

It was very surprising. I mean, if you look at her background and her experiences from Harvard and Columbia, women were a minority — and it was a fighting minority. I was studying law in Sweden at that time, and there were not very many equality questions involved in studying law. Also, the society was to a very different degree arranged so that women could marry and continue their studies — all these [things] that Ruth had had to fight for. And also to have children. There were kindergartens or childcare centers where the kids were taken care of. Ruth put her child in one of those during her stay in Lund, and she was very, very pleased with the facilities that were offered.

What other things around the climate around gender politics at that time in Sweden do you think influenced Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s thinking?

I think the state, to a very large extent, engaged itself in facilitating that women were treated equally in many more aspects than there were in the United States.

And talks with my mother, who was a feminist, a very early feminist, and talks in Stockholm, with a Swedish author who was called Eva Moberg, who wrote about the gender issues at that time, also gave her a lot of food for thought.

Related: Women’s rights are not explicitly recognized in US

Did Ginsburg have an influence on your own career in the law?

I studied law in New York in 1968, ’69. I was more mature by that time and we discussed more of the issues of women’s rights, and she got me to write an article on the situation in Norway a couple of years later.

Of course, her seriousness and her belief in law as a possible tool to obtain goals were transmitted to me, too. So, yes she did have an impact.

This image provided by the Supreme Court shows Ruth Bader Ginsburg types while on a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship in Italy in 1977.Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

This image provided by the Supreme Court shows Ruth Bader Ginsburg types while on a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship in Italy in 1977.Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

This interview was edited and condensed for clarity.

The post RBG’s early days in Sweden shaped her fight for women’s equality appeared first on The World from PRX.

21 September 2020, 7:15 pm - Social media censorship in Egypt targets women on TikTok

Looking at Haneen Hossam’s TikTok account, one might wonder why her content landed the Egyptian social media user in jail. In one post, she explains for her followers the Greek mythological story of Venus and Adonis, which is also a Shakespeare poem.

Mawada al-Adham does similarly anodyne things that are familiar to anyone who observes such social influencers, like giving away iPhones and driving a fancy car.

They are just two of the nine women arrested in Egypt this past year for what they posted on TikTok. Mostly, their videos are full of dancing to Arabic songs, usually a genre of electro-pop, Egyptian sha’abi folk music called mahraganat, or festival tunes. The clips feature a typically TikTok style — with feet planted, hands gesticulating and eyebrows emoting.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration has put TikTok and its Chinese parent company, ByteDance, in its sights with another escalation against Beijing. The US Commerce Department announced Friday that TikTok, and another Chinese-owned app, WeChat, would be blocked from US app stores.

In Egypt, the arrests are about dictating morality rather than any kind of geopolitical struggle or international tech rivalry. But what exactly the government finds legally objectionable about these women’s online content is ambiguous.

“They themselves would have never imagined that they would go to jail and be sentenced for what they were doing, because what they’re doing is basically what everyone else does on social media.”

Salma El Hosseiny, International Service for Human Rights“They themselves would have never imagined that they would go to jail and be sentenced for what they were doing because what they’re doing is basically what everyone else does on social media,” said Salma El Hosseiny of the International Service for Human Rights, a nongovernmental organization based in Geneva. “Singing and dancing as if you would at an Egyptian wedding, for example.”

Hosseiny said that these women were likely targeted because they’re from middle- or working-class backgrounds and dance to a style of music shunned by the bourgeoisie for scandalous lyrics that touch on taboo topics.

“You have social media influencers who come from elite backgrounds, or upper-middle class, or rich classes in Egypt, who would post the same type of content. These women are working-class women,” she added. “They have stepped out of what is permitted for them.”

Criminalizing the internet

They were charged under a cybercrime law passed in 2018, as well as existing laws in the Egyptian Penal Code that have been employed against women in the past.

Yasmin Omar, a researcher at The Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy in Washington, said the cybercrime law is vague when it comes to defining what’s legal and what isn’t.

“It was written using very broad terms that could be very widely interpreted and criminalizing a lot of acts that are originally considered as personal freedom,” she said. “Looking at it, you would see that anything you might post on social media, anything that you may use [on] the internet could be criminalized under this very wide umbrella.”

Egypt’s cybercrime law is part of a larger effort by the government to increase surveillance of online activities. As TikTok became much more popular during the pandemic, prosecutors started looking there too, Omar said.

“When I write anything on my social media accounts, I know that it could be seen by an official whose job it is to watch the internet and media platforms,” said Omar, who added that that surveillance often leads to widespread repression.

“The state is simply arresting whoever says anything that criticizes its policy, its laws, its practices … even if it’s just joking. It’s not even allowed.”

Related: One woman’s story highlights national wave of repression and sexual violence

The arrests of TikTokers shows that this law isn’t just about monitoring and controlling political dissent, but is used to police conservative social norms.

Menna Abdel Aziz, 17, made a live video on Facebook. Her face was bruised and she told viewers that she had been raped and was asking for help.

The police asked her to come in, and when she did, Omar said, they looked at her TikTok account and decided she was inciting debauchery and harming family values in Egypt — essentially blaming the victim for what had occurred.

This past summer, there were a number of particularly shocking allegations involving rape and sexual assault in Egypt. First, dozens of women accused a young man at the American University in Cairo (AUC) of sexual violence ranging from blackmail to rape. And in another case, a group of well-connected men were accused of gang-raping a young woman in Cairo’s Fairmont Hotel in 2014 and circulating a video of the act.

The cases garnered a lot of attention within Egypt. Many Egyptian women were shocked by the horrible details of the cases but not surprised about the allegations or that the details had been kept under wraps for so long.

“In Egypt, sexual violence and violence against women is systematic,” Hosseiny said. “It’s part of the daily life of women to be sexually harassed.”

‘To go after women’

A UN Women report in 2014 said that 99.3% of Egyptian women reported being victims of sexual harassment. Yet, women are often culturally discouraged from reporting sexual harassment in the traditional society.

“They are investing state resources to go after women who are singing and dancing on social media, and trying to control their bodies, and thinking that this is what’s going to make society better and a safer place,” Hosseiny said, “by locking up women, rather than by changing and investing in making Egypt a safe place for women and girls.”

When prosecutors started investigating the accused in that high-profile Fairmont case, it looked like real progress and a victory for online campaigning by women. The state-run National Council for Women even encouraged the victim and witnesses to come forward, promising the women protection. But that pledge by the state did not materialize.

“Somehow, the prosecution decided to charge the witnesses,” said Omar, the researcher. “Witnesses who made themselves available, made their information about their lives, about what they know about the case — all this information was used against them.”

“Witnesses who made themselves available, made their information about their lives, about what they know about the case — all this information was used against them.”

Yasmin Omar, Tahrir Institute for Middle East PolicyOnce again, Egyptian authorities looked at the women’s social media accounts, and then investigated the women for promoting homosexuality, drug use, debauchery and publication of false news. One of the witnesses arrested is an American citizen.

When pro-state media outlets weighed in on the TikTok cases, they also had a message about blame, Hosseiny said. The coverage used sensational headlines and showed photos of the women framed in a sexual way. This contrasted with the depictions in rape cases in which the accused men’s photos were blurred and only their initials printed.

Social media has played an important role in Egyptian politics during the last decade. In 2011, crowds toppled the regime of military dictator Hosni Mubarak. That uprising was in part organized online with Twitter and Facebook. In 2018, the former army general, and current president, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, said he would maintain stability in Egypt.

“Beware! What happened seven years ago is never going to happen again in Egypt,” he swore to a large auditorium full of officials.

Related: Five years of Sisi’s crackdown has left ‘no form of opposition’ in Egypt

Samer Shehata, a professor at the University of Oklahoma, said Egypt’s military-backed regime is wary of the implications of anything posted online, even if it’s just dancing.

“I think there has been a heightened paranoia as a result of hysteria … about the possible political consequences of social media,” he said. “I think that they certainly have those kinds of concerns in the back of their minds as well.”

Of the nine women charged with TikTok crimes, four have been convicted and three have appeals set for October.

Menna Abdel Aziz, the young woman who called for help online, was just released from detainment Wednesday and is being dismissed with no charges.

The post Social media censorship in Egypt targets women on TikTok appeared first on The World from PRX.

18 September 2020, 7:10 pm - A racial slur remains in hundreds of place names throughout North America

George Floyd’s killing this past spring has sparked battles throughout the country, particularly around places and things that evoke historical injustices and inequalities, like statues of Confederate leaders. But there are also clashes throughout North America around an often-used word that many don’t know is a racial slur: “squaw.”

That’s beginning to change now as places like Squaw Valley Alpine Meadows in California’s Sierra mountains are taking action to stop using the term.

“We’re probably the most well-known place with that name,” said Ron Cohen, CEO of Squaw Valley Alpine Meadows. The resort was named by the first white settlers who stumbled into the valley; they met a group of Native American women the settlers called squaws, and so they named it Squaw Valley. The consensus among Indigenous people today is that the term is a sexual slur that demeans and dehumanizes Indigenous women.

Related: Video of police beating Indigenous chief fuels ongoing anti-racism protests in Canada

Roughly a hundred years later, the world gathered in the same spot for the 1960 Winter Olympics. Squaw Valley was transformed into an elegant ski resort that, afterward, attracted generations of families.

“Our guests — their grandparents skied here, their grandparents took their parents to learn to ski here when they were little kids,” Cohen said. “Those parents grew up and brought their kids here to learn to ski.”

Some people are attached to the resort’s name because it’s connected to so many family memories, Cohen said. But after Floyd’s murder, he said he couldn’t ignore the emails he received from people offended by the name. And Cohen said that’s what led to a decision announced last month to change the resort’s name.

“I think it’s entirely understandable that our announcement would kick off discussions elsewhere,” he said.

The resort’s work to determine a new name began right away, and it will be implemented in 2021.

More often than not, it’s Indigenous women leading the fight to rid the word squaw from public places.

Related: Toronto’s first black police chief resigns

One of them is Jude Daniels, from Alberta, Canada, who is Métis. She lives at the base of a mountain peak that white explorers named Squaw’s Tit.

“So, I saw that peak every single day for the last 15 years,” she said. “And even though I have with one exception been treated with respect, I know that odiously named peak is part of the systemic discrimination that is one of the root causes of the huge rates of violence against Indigenous women across Canada.”

Last year, a Canadian government report found that failures by law enforcement have led to systemic violence against Indigenous women and girls. They are three to five times more likely than other women to be victims of violence. Daniels first learned the harm of the word squaw when she was a child in school.

“Kids would say things to me, like ‘dirty squaw,’ “dirty Indian,”” she remembered.

In 2000, Canada’s British Columbia province eliminated the use of the word squaw from all its place names after receiving requests from local Indigenous leaders. But that’s not the case in neighboring Alberta.

“So it happened right next door,” Daniels said. “And here we are in Alberta, and we still have to place names with the word squaw in it.”

Related: Indigenous groups in Canada fight to stay closed as restrictions ease

Daniels has waged a yearslong campaign to change the name of the mountain peak with the help of pro bono attorneys. Their fight got a sudden boost this summer after Floyd’s death. Daniels said now the local community is overwhelmingly supportive of getting rid of the name. It’s just a matter of choosing another one.

Other communities have put up more resistance, as Mandy Steele found. She’s a borough council member in Fox Chapel, an affluent suburb of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. She learned what squaw meant this summer at a Black Lives Matter rally in a park.

“The park happened to be called Squaw Valley Park,” Steele said. “And at that rally, a Native American woman spoke.”

The woman, Michele Leonard, talked about what the word squaw means, and why it should be changed. She turned out to be one of Steele’s constituents, who happens to live on a street called Squaw Run Road. Steele put forward a motion to eliminate all the uses of squaw in names there.

“And the council instead decided to put the task of determining whether or not the word is a slur to a committee of residents, in a community that’s largely white and privileged,” Steele said.

At that council meeting, on Zoom, Leonard had three minutes to comment.

Related: Canadian activists say they’re being targeted by China

“I don’t think you understand how painful it has been to hear you speak,” Leonard said, reminding council members that she has lived on Squaw Run Road for 30 years. “I am the Native American woman who has to send out greeting cards with a return address with that horrible word. … I had to get a post office box so I would not use that address for some of the Indian member organizations I belong to.”

Leonard is on the committee that will decide whether the word warrants being removed. She said she’ll argue that while the early white settlers might not have not known they were using a slur, people should recognize that now, and take action.

The post A racial slur remains in hundreds of place names throughout North America appeared first on The World from PRX.

17 September 2020, 6:35 pm - Latin American women are disappearing and dying under lockdown

It’s a pandemic within the pandemic. Across Latin America, gender-based violence has spiked since COVID-19 broke out.

Almost 1,200 women disappeared in Peru between March 11 and June 30, the Ministry of Women reported. In Brazil, 143 women in 12 states were murdered in March and April — a 22% increase over the same period in 2019.

Reports of rape, murder and domestic violence are also way up in Mexico. In Guatemala, they’re down significantly — a likely sign that women are too afraid to call the police on the partners they’re locked down with.

The pandemic worsened but did not create this problem: Latin America has long been among the world’s deadliest places to be a woman.

Don’t blame ‘machismo’

I have spent three decades studying gendered violence as well as women’s organizing in Latin America, an increasingly vocal and potent social force.

Women demand justice for Mexico’s many murdered women at a protest against gender violence in Mexico City, Aug. 15, 2020. Nadya Murillo/Barcroft Media via Getty Images

Women demand justice for Mexico’s many murdered women at a protest against gender violence in Mexico City, Aug. 15, 2020. Nadya Murillo/Barcroft Media via Getty Images

Though patriarchy is part of the problem, Latin America’s gender violence cannot simply be attributed to “machismo.” Nor is gender inequality particularly extreme there. Education levels among Latin American women and girls have been rising for decades and — unlike the US— many countries have quotas for women to hold political office. Several have elected women presidents.

My research, which often centers on Indigenous communities, traces violence against women in Latin America instead to both the region’s colonial history and to a complex web of social, racial, gender and economic inequalities.

I’ll use Guatemala, a country I know well, as a case study to unravel this thread. But we could engage in a similar exercise with other Latin American countries or the US, where violence against women is a pervasive, historically rooted problem, too — and one that disproportionately affects women of color.

In Guatemala, where 600 to 700 women are killed every year, gendered violence has deep roots. Mass rape carried out during massacres was a tool of systematic, generalized terror during the country’s 36-year civil war, when citizens and armed insurgencies rose up against the government. The war, which ended in 1996, killed over 200,000 Guatemalans.

Mass rape has been used as a weapon of war in many conflicts. In Guatemala, government forces targeted Indigenous women. While Guatemala’s Indigenous population is between 44% and 60% Indigenous, based on the census and other demographic data, about 90% of the over 100,000 women raped during the war were Indigenous Mayans.

Testimonies from the war demonstrate that soldiers saw Indigenous women as having little humanity. They knew Mayan women could be raped, killed and mutilated with impunity. This is a legacy of Spanish colonialism. Starting in the 16th century, Indigenous peoples and Afro descendants across the Americas were enslaved or compelled into forced labor by the Spanish, treated as private property, often brutally.

Some Black and Indigenous women actually tried to fight their ill treatment in court during the colonial period, but they had fewer legal rights than white Spanish conquerors and their descendants. The subjugation and marginalization of Black and Indigenous Latin Americans continues into the present day.

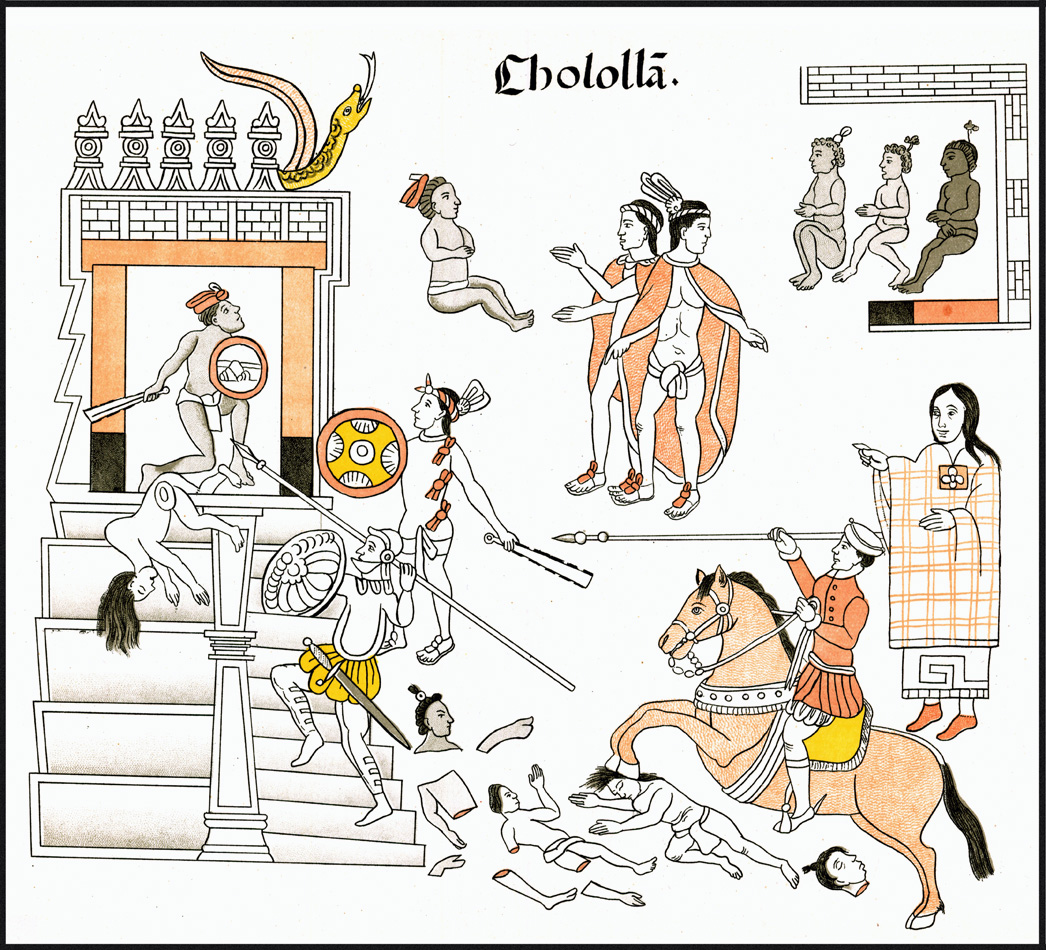

A depiction of the 1519 Cholula Massacre by Spanish conquistadors in 1519, made by Mexico’s Indigenous inhabitants.Wikimedia Commons

A depiction of the 1519 Cholula Massacre by Spanish conquistadors in 1519, made by Mexico’s Indigenous inhabitants.Wikimedia Commons

Internalized oppression

In Guatemala, violence against women affects Indigenous women disproportionately, but not exclusively. Conservative Catholic and evangelical moral teachings hold that women should be chaste and obey their husbands, creating the idea that men can control the women with whom they are in a sexual relationship.

In a 2014 survey published by the Latin American Public Opinion Project at Vanderbilt University, Guatemalans were more accepting of gender violence than any other Latin Americans, with 58% of respondents saying suspected infidelity justified physical abuse.

Women as well as men have internalized this view. During my research in Guatemala and Mexico, many women shared stories about how their own mothers, mothers-in-law or neighbors told them to aguantar — put up with — their husbands’ abuse, saying it was a man’s right to punish bad wives.

The media, police and often even official justice systems reinforce strict constraints on women’s behavior. When women are murdered in Guatemala and Mexico — a daily occurrence — headlines often read, “Man Kills His Wife Because of Jealousy.” In court and online, rape survivors are still accused of “asking for it” if they were assaulted while out without male supervision.

A Mexican newspaper exclaims ‘Burnt Alive!’ to tout a story about a murdered woman, June 7, 2015.Omar Torres/AFP via Getty Images

A Mexican newspaper exclaims ‘Burnt Alive!’ to tout a story about a murdered woman, June 7, 2015.Omar Torres/AFP via Getty Images

How to protect women

Latin American countries have made many creative, serious efforts to protect women.

Seventeen have passed laws making feminicide — the intentional killing of women or girls because they are female — its own crime separate from homicide, with long mandatory prison sentences to try to deter this. Many countries have also created women-only police stations, produced statistical data on feminicide, improved reporting avenues for gendered violence and funded more women’s shelters.

Latin America has long been one of the world’s most dangerous regions for women. Crosses mark where the corpses of eight missing women were found outside Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, in 2008.Alfredo Estrella/AFP via Getty Images

Latin America has long been one of the world’s most dangerous regions for women. Crosses mark where the corpses of eight missing women were found outside Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, in 2008.Alfredo Estrella/AFP via Getty Images

Guatemala even created special courts where men accused of gender violence — whether feminicide, sexual assault or psychological violence — are tried.

Research I conducted with my colleague, political scientist Erin Beck, finds that these specialized courts have been important in recognizing violence against women as a serious crime, punishing it and providing victims with much-needed legal, social and psychological support. But we also found critical limitations related to insufficient funding, staff burnout and weak investigations.

There is also an enormous linguistic and cultural gap between judicial officials and in many parts of the country the largely Indigenous, non-Spanish-speaking women they serve. Many of these women are so poor and geographically isolated they can’t even make it into court, leaving flight as their only option of escaping violence.

The collective body

All these efforts to protect women — whether in Guatemala, elsewhere in Latin America or the US — are narrow and legalistic. They make feminicide one crime, physical assault a different crime, and rape another — and attempt to indict and punish men for those acts.

But they fail to indict the broader systems that perpetuate these problems, like social, racial and economic inequalities, family relationships and social mores.

Some Indigenous women’s groups say gendered violence is a collective problem that needs collective solutions.

Gendered violence in Guatemala disproportionately affects Indigenous women.Johan Ordonez/AFP via Getty Images

Gendered violence in Guatemala disproportionately affects Indigenous women.Johan Ordonez/AFP via Getty Images

“When they rape, disappear, jail or assassinate a woman, it is as if all the community, the neighborhood, the community or the family has been raped,” said the Mexican Indigenous activist Marichuy at a rally in Mexico City in 2017.

In Marichuy’s analysis, violence against one Indigenous woman is the result of an entire society that dehumanizes her people. So simply sending the abuser to prison is not sufficient. Gendered violence calls for a punishment that both implicates the community and the offender — and tries to heal them.

Some Mexican Indigenous communities have autonomous police and justice systems, which use discussion and mediation to reach a verdict and emphasize reconciliation over punishment. Sentences of community service — whether construction, digging drainage or other manual labor — serve to both punish and socially reintegrate offenders. Terms range from a few weeks for simple theft to eight years for murder.

Stopping gendered violence in Latin America, the US or anywhere will be a complicated, long-term process. And grand social progress seems unlikely in a pandemic. But when lockdowns end, restorative justice seems like a good way to start helping women and our communities.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit news organization dedicated to unlocking ideas from academia, under a Creative Commons license.

The post Latin American women are disappearing and dying under lockdown appeared first on The World from PRX.

25 August 2020, 4:20 am - Polish activists fight against anti-LGBT movement

This past Sunday, hundreds of far-right nationalists gathered at the gates of the University of Warsaw in Poland. They rallied against “LGBT aggression” and chanted taunts about a well-known activist known as Margot. Another group countered them, rainbow flags in hand, while a massive police presence kept them apart.

Margot — Małgorzata Szutowicz — a 25-year-old nonbinary person who uses female pronouns, runs a radical, queer collective in Warsaw called Stop Bzdurom, or Stop the Nonsense, with her partner, Łania Madej, 21.

Related: In Turkey, a conservative push to remove domestic violence protections is met with an uproar

The collective, and particularly Margot, have become the face of the LGBT rights movement in Poland in recent days. Margot is currently being held in two-month, pretrial detention for assault and property damage charges after a dispute with a van driver from an organization spreading anti-LGBT messages.

Supporters inside the country and beyond continue to call for her release, and a range of celebrities — from the writer Margaret Atwood to the actor Stellan Skarsgaard — are calling for greater LGBT rights in Poland.

Poland is considered the worst country in the European Union in terms of gay rights. The cultural divisiveness of the issue came through in the narrow reelection of Andrzej Duda for president in July. Duda, backed by the nationalist Law and Justice (PiS) party, campaigned on an anti-LGBT platform, calling it an “ideology worse than communism.”

According to an IPSOS poll in late 2019, 1 in 4 Poles said the LGBT movement is the country’s greatest threat. Nearly a third of Polish towns and cities have declared themselves as “LGBT-free zones,” a move that resulted in the European Union denying funding to certain towns.

Stop Bzdurom’s name is a reference to a proposed, “Stop Pedophilia” bill that opened the door to legal action for teaching sexual education. The bill’s supporters blamed what they call the “LGBT lobby” for promoting sexual discussions in schools and “grooming” children toward homosexuality.

Related: As Poland’s Duda seeks ‘Trump bump,’ Putin looks to revise history

These are messages echoed by the anti-abortion, Pro-Right to Life Foundation, which sends vans around Polish cities — displaying banners of aborted fetuses and anti-gay messages that they also broadcast through megaphones. The organization is also against the so-called LGBT lobby.

Their messages often connect homosexuality with pedophilia and child abuse.

“A few hours every day, they ride around the city with huge speakers and just scream about us raping children and stuff like that, so we started spray painting the cars.”

Łania Madej, Polish LGBT acvitist“A few hours every day, they ride around the city with huge speakers and just scream about us raping children and stuff like that, so we started spray painting the cars,” Madej said.

Margot and Madej would also stand in the street to block them, sometimes remove the license plates, and one day in June, they fought with a driver. The drivers know the activists and often pass by where they live. That day, a fight broke out that resulted in Margot’s later arrest and charges for property destruction and assault, though Margot says she only shoved the driver and he was not injured. She was released after a night in jail.

Tensions around gay rights have been building in socially conservative Poland for years. Conservative governments in Europe have courted the right by scapegoating vulnerable minority groups.

Related: Young people in Poland are rediscovering their Jewish roots

Karolina Gierdal, a lawyer with the organization Campaign Against Homophobia, says refugees used to be the target in Poland. In the past few years, queer people have emerged as the new boogeyman.

“You can create an enemy that does not necessarily have to take away your money like the refugees are supposed to do, but they can take away you feeling Polish, you being Polish. They can take away your culture. Or they can destroy your family and hurt your children,” she explained via Skype.

Gierdal says her organization works to improve rights for queer people through policy and by normalizing the issues. But this doesn’t seem to be enough right now, she says.

Margot and Madej say this is where they come in. Margot says they push the boundaries to make space for others to operate in.

“We are too radical for everybody, but we support our supporters and our queer activists and they move the middle part,” she explained during an interview with The World prior to her detention.

“We are the people who will destroy the van and bring attention to it and the other organizations are the people who are going to maybe take care of that with laws and stuff,” Madej said.

Related: Berlin ‘abortion aunts’ help Polish women access safe abortions

Earlier this month, the two took another step. With other activists, they hung rainbow flags on monuments, including a statue of Christ. For many devout Catholics in the country, this was a highly provocative message. Margot, Madej and one other activist were briefly held on charges of offending religious sentiments.

The next day, Margot was taken back into custody for the earlier charges related to the incident with the van driver, now to serve two-month pretrial detention. A crowd blocked the police car holding her and 48 people were arrested. Gierdal says both Margot’s long detention and the seemingly random arrests were excessive.

Madej says they don’t expect to change the minds on the right but want to help queer Polish youth feel less alone.

“We do it only for the queer kids who run with us and they have a little bit of fun and feel brave for 10 minutes.”

Łania Madej, Polish LGBT acvitist“We do it only for the queer kids who run with us and they have a little bit of fun and feel brave for 10 minutes,” she said, referring to their activism around the anti-LGBT vans.

A day later, on Aug. 8, thousands gathered at the city center in protest.

Maria Kobus, a 69-year-old accountant, was one of them. Though she says she’s not an activist, she feels queer people are being denied equal rights. Kobus’ daughter lives outside the country with her wife.

“She will never come back,” Kobus said.

Smaller protests sprung up around Poland and even some other European cities. But not all Polish supporters think activism is the right way. From a park outside her Warsaw apartment, 78-year-old Helena Kośnicka remembers officiating the unofficial wedding of her gay neighbors. Gay marriage is not legal in Poland.

Kośnicka supports LGBT rights. But she doesn’t agree with protesting.

“They shouldn’t do silly things too much. Because that annoys people,” she said.

But the activists say maybe it’s time to start making more noise. Some are asking if this could be Poland’s Stonewall, the 1969 riots in New York City that were a turning point for the gay rights movement in the US.

“I believe we really want Polish Stonewall because we’re so tired and we want something to change,” said Gierdal, the lawyer.

The post Polish activists fight against anti-LGBT movement appeared first on The World from PRX.

19 August 2020, 7:32 pm - More Episodes? Get the App

- https://www.pri.org/

- en-us

Your feedback is valuable to us. Should you encounter any bugs, glitches, lack of functionality or other problems, please email us on [email protected] or join Moon.FM Telegram Group where you can talk directly to the dev team who are happy to answer any queries.

Microbiome (Video)

Microbiome (Video)

Women's Issues (Video)

Women's Issues (Video)

Department of Social Policy and Intervention

Department of Social Policy and Intervention

Global Health

Global Health