Welcome to the Food Court

G. S. Jameson & Company

Welcome to the Food Court is an opportunity to deep-dive into legal issues related to food law from people who work in law and in the food sector. We focus on how food sector stakeholders interact with the institutions that regulate our food. This podcast won a coveted Canadian Law Blog Award for Blog of the Year for 2016 and Best New Blog in 2015. Learn more at food.gsjameson.com

- Food Recall: how missteps in the implementation of a recall procedure can lead to judicial action

Mistakes happen. With food manufacturing, mistakes can take the form of malfunctioning equipment or cross-contamination of ingredients. Sometimes a key, trusted player in the supply chain sources an ingredient from a new supplier to meet demand, and that new ingredient contains an undeclared allergen. Sometimes, despite rigorous testing and sampling procedures, salmonella finds its way onto the production line and contaminates a LOT.

For most stakeholders in the food value chain, mistakes are terrifying. Mistakes signal lost product, lost revenue, lost time, and energy, but most importantly, lost trust with consumers who relied on the safety of a consumable. Mistakes can signal the need to enact a voluntary recall of product, and thus converse with the regulator – the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (“CFIA”) and/or Health Canada.

Under the Safe Food for Canadians Act (“SFCA”), regulated entities are required to prepare, keep and maintain a recall procedure as part of their Preventative Control Plan (“PCP”). Further, regulated entities have to conduct recall simulations at least once every twelve months to test the viability of their recall procedure. These documents and drills are designed to prepare regulated entities for the probable: a mistake. And while they should serve to ensure corrective action in the face of a mistake, thereby eliminating the fear of judicial action, the reality is that any oversight or misstep, in enacting a recall procedure, can lead to court action, and in particular a class action lawsuit.

With the 2023 decision of Bowman v. Kimberly-Clark Corporation (found here), we learn that recall and refund programmes can be extensive and broad in application, but still not address alleged harm done to all parties affected by the recall. While this is not a food-related decision – it addresses bacteria found on flushable wipes in 2020 – Justice Matthews’ decision to allow a class action lawsuit to proceed for the Personal Injury Subclass of claimants, because they did not receive adequate notice of their right to make a claim for personal injury nor adequate compensation, demonstrates the need for regulated parties to engage all levels of the supply chain with their recall – down to the consumer – and to document the process. An oversight, in this case, resulted in Justice Matthews’ decision to allow a class proceeding to commence, in order to contemplate a wrong faced by those who claimed to suffer personal injury as a result of using the recalled lots of product.

It would be an understatement to stress the importance of being thorough with one’s recall procedure. Kimberly-Clark Corporation, for example, went to great lengths to ensure their contaminated wipes were isolated, destroyed, and generally removed from the market. Kimberly-Clark Corporation worked with the United States Food and Drug Administration and Health Canada to initiate a recall notice, and issue it to retailers. They, then, followed up with retailers by phone to ensure affected product was removed from shelves. Following this, Kimberly-Clark set up a webpage, dedicated to the recall, with instructions for consumers. They posted about their recall on Facebook and Twitter. The recall was picked up by news channels across the country, and Health Canada published a notice on its recall website. Some retailers even sent recall notices to their purchasers, on Kimberly-Clark Corporation letterhead. Consumers were provided with refunds, albeit undocumented in terms of quantum and rationale for quantum, through an expanded customer service team that Kimberly-Clark hired to deal with incoming inquiries and refund requests. And yet, these actions were not enough for Justice Matthews to find the non-judicial alternative of a recall to be sufficient in ensuring access to justice, judicial efficiency, or behaviour modification: the three objectives to consider when determining whether a class proceeding is the appropriate forum to redress a wrong.

The case of Kimberly-Clark is not an anomaly, though. A review of case law shows a history of class action claims, following an initiated recall. In 2018, for example, the Ontario Superior Court of Justice heard the case of Richardson v. Samsung (here), regarding a recall for defective cell phones. However, unlike in Kimberly-Clark, a class action lawsuit did not proceed against Samsung Electronics. Judge Rady stated, at para. 71 of the decision, that “class actions are an important vehicle to redress wrongs to those who would not otherwise bring action because it would be economically ill-advised.” Judge Rady determined that Samsung Electronics’ recall programme met the needs of access to justice, and therefore the corporation did not require behaviour modification. She wrote, “in my view, the defendant’s prompt response in concert with Health Canada to safety issues, the recall, the termination of sales, and the compensation package, demonstrates the response of a responsible corporate citizen. It is behaviour that should be encouraged rather than discouraged.” In other words, Samsung Electronics had implemented a recall programme broad enough to redress wrongs throughout the supply chain: from consumer, through to retailer, and up to distributor.

To utilize an example relevant to food, the case of Romero v. The Meat Shop at Pine Haven (here) was heard in Alberta, in 2022, to determine whether a class action lawsuit was the preferable proceeding for claimants to claim damages for consumption of pork contaminated with E.coli. Ultimately, despite issuance of a recall notice and working with CFIA and Health Canada to address the contamination, a class action proceeding was found to be a fair and efficient process for resolution of the common issues. Likewise, a case before the Supreme Court of Canada, in 2020, saw Mr. Sub franchisees pursue a class action lawsuit against Maple Leaf Foods Inc. for reputational damage, suffered during a voluntary recall of deli meats, as well as economic loss. In this instance, the food manufacturer (i.e., Maple Leaf Foods) had an obligation to ensure the safety of consumers, but also to mitigate the economic, and reputational, loss of its supply chain.

With this myriad of case law, related to deficiencies in recall procedures, what should regulated parties do, then, when faced with mistake?

First, the preparation and maintenance of a thorough recall procedure, and more generally a PCP, is important to ensure that everybody understands their role when faced with mistake, and steps are followed to correct mistake. Regulated entities can make both preventative and protective decisions, related to their recall procedures, to avoid greater cost and stress when mistake arises.

If a regulated entity is unsure about their recall procedure or PCP, contact a legal professional to review what’s in place.

Second, if a regulated entity determines that voluntary recall is the appropriate action to ensure the health and safety of consumers, consider engaging a legal professional to negotiate with the regulator on your behalf. Have a legal professional guide you through this crisis situation, as sometimes the stress of a recall leads to oversight or misstep.

While a legal professional is not a guarantee against court action, engaging one could make the difference between a Kimberly-Clark Corporation and a Samsung Electronics. And while regulatory processes are generally preferred to judicial action in Canada, and courts provide a great deal of deference to the decisions of non-judicial bodies, class action lawsuits will continue to exist as an option for classes of claimants that, otherwise, do not believe their concerns have been addressed or fixed. For regulated parties, this serves as a reminder to prepare for mistake, and work to ensure corrective actions are implemented throughout the supply chain when faced with mistake and voluntary, or mandated, recall.

For assistance with any of the above, please reach out to us at [email protected].

21 September 2023, 3:27 pm - Contested Territories: CFIA Launches Consultation on Country of Origin Claims

In 2017, bottles of wine appeared in Liquor Control Board of Ontario (“LCBO”) stores, which displayed labels with “Product of Israel” as their Country of Origin. Some consumers took issue with this origin claim, though, as the wine came from the West Bank – a contested territory with a history of Palestinian existence. These consumers felt that it was erasure to label the wines as Israeli when, in fact, the grapevines could be found in the West Bank. Complaints to the LCBO ensued, which prompted the LCBO to contact the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (“CFIA”) for guidance, and then a stickering campaign to re-label the wines as “Product of West Bank.”

However, the discussion did not stop there, as some in the Canadian, Jewish community disagreed with the required stickering of these wines, and demanded that CFIA re-evaluate its decision to revise the label and halt importation. Suddenly, CFIA was forced to take a position in an intensely geo-political, territorial dispute – wildly outside of the purview or mandate of Canada’s humble regulator of foods, feeds, seeds, and so on.

GSJ & Co. submitted an Access to Information Act (“ATIP”) request in November of 2022 regarding this very issue. The request revealed nearly 3,000 pages of both panicked and measured correspondence, research, and surprising collaboration between the CFIA, Global Affairs Canada, the LCBO and the provinces, in an attempt to understand the situation, provide a fair decision, and attempt to align CFIA’s position with Canadian foreign policy on the matter.

In the face of this scrutiny, CFIA’s decision, to have the importer sticker these wines “Product of West Bank”, was brought before Federal Court for a judicial review in Kattenburg v. Canada (Attorney General) and determined to be incorrect. An appeal was dismissed at the Federal Court of Appeal in 2020 and the Supreme Court of Canada denied an Application for Leave in 2021. Per the Canada-Israel Free Trade Agreement, and the requirement of labels to display a Country of Origin – not territory (barring some exceptions related to the Americas) – the Federal Court ruled that wines from the West Bank are appropriately labelled “Product of Israel”, in keeping with the Food and Drug Regulations (“FDRs”).

The discussion persisted, though, and in April of 2022, further complaint occurred when Palestinian consumers found bottles of wine, labelled as “of Palestine”, stickered over with a “Product of Israel” sticker.

There is an ongoing need to examine how we label origin claims on food and beverage, and what may be acceptable to display on a label without providing false, misleading or deceptive information to consumers. Canada’s approach to country-of-origin labelling (“COOL”) has been under scrutiny for several years. Our firm was involved in a CBC Marketplace report on apple juice labelling, for example, and Canada’s approach to labelling wine made from or blended with imported grapes took years of lobbying by domestic vintners before CFIA updated its policy in the late 2010s.

With all of this background, it is no surprise that the CFIA has launched a Consultation on COOL, which runs until October 10, 2023, and asks whether food products from contested territories may display the geographic region or territory where the food was produced, to help clarify where the product came from, without being false or misleading under Canadian labelling regulations.

Our first thought in response to this Consultation is: would a label be required to maintain the Country-of-Origin declaration, in addition to a geographic region or territory? And if so, what sort of font restrictions apply? If a bottle of wine states, “Product of Israel”, but then lists the West Bank in smaller font underneath this country declaration, how offensive may that be to some people?

We note that the CFIA’s Consultation specifically states that it does not pertain to a specific imported food or the status of a specific contested territory, and that many contested territories exist, within internationally recognized countries, which may be affected by similar labelling restrictions. And there are more ongoing territorial disputes than one might think: grain from Donetsk, Kherson, and Luhansk Oblasts come to mind. But we would be remiss to ignore the timeliness of publishing this Consultation so soon after the “Product of Israel” wine discussion: this is clearly about the West Bank.

We should also point out that origin claims are required only on specific food and beverage products: Country-of-Origin labelling must appear on brandy and wine, while a foreign state must appear on the labels of imported dairy products, eggs and processed egg products, fish, fresh fruit and vegetables, honey, maple and meat products, and some processed fruit and vegetable products.

In other words, this Consultation should be aimed at stakeholders involved with the importation of these specific food and beverage products, as they will be most affected in a commercial sense, but the CFIA also wants to hear from consumers, academics, and the food industry, in general. Without initial awareness from the general public about “Product of Israel” claims on wine, this discussion could have gone unattended to for awhile; thus, we encourage anybody with an interest in this topic, or a stake in the result, to reach out to the CFIA and provide an opinion.

For more information on the Consultation, please visit the CFIA website.

For labelling reviews, prior to bringing your product to market, or for help with making or responding to an ATIP request, please do not hesitate to reach out to us at [email protected].

9 August 2023, 2:42 pm - Food Composition Standards: CFIA Opens Consultation to Remove Standards from Regulations

Compositional standards for food, prescribed by law and found in the Canadian Food and Drug Regulations (“FDRs”) and Safe Food for Canadians Regulations (“SFCRs”), often require thorough examination by international and national stakeholders for any food product that is imported, exported, or otherwise transported across borders. And it’s no secret that Canadian food standards are some of the strictest in the world, often requiring stakeholders to re-assess their products for compliance on the Canadian market, and/or developing a new common name for their food product because the product does not fit the standard. All of this can be very frustrating for anybody looking to access the Canadian market, thereby limiting innovation.

At GSJ & Co., for example, we frequently assess international dessert products for compliance with Canadian food standards, and often encounter mascarpone cheese coagulated through the use of citric acid. Citric acid, as you may or may not know, is a naturally occurring acid found in many citrus fruits, but is classified as a food additive by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (“CFIA”) and Health Canada. Per the FDRs, mascarpone cheese must be coagulated with bacteria in order to bear the common name, “mascarpone cheese”. This means that many international stakeholders, that manufacture a, otherwise compliant, cheese with citric acid cannot market their cheese as “mascarpone cheese”, and instead must resort to calling their cheese a “cheese product”, or revise the process altogether. This is particularly cumbersome if the food product is already manufactured for sale, as is, in other countries around the world.

Thus, it came as a welcome surprise to see that the CFIA opened a consultation on June 23rd to determine whether food compositional standards should be removed from the FDRs, and to a lesser extent the SFCRs, to add them to a document Incorporated by Reference (“IbR”). Documents IbR exist as part of Regulations without being in the Regulations, thereby making it easier to modify and change them.

CFIA’s consultation also seeks to remove non-essential elements from compositional standards to focus on the essential elements of food. CFIA suggests that non-essential elements could include production elements, such as sweetening agents, or any element that relates to health, safety or nutrition and is governed by Health Canada through a separate process (i.e., fortification requirements or food additives).

CFIA intends to encourage stakeholders to request modifications to compositional standards whenever a need presents itself. This request would be submitted to CFIA, with supporting documentation, and would either show support from similar stakeholders in its application, or would be available for further consultation. CFIA, then, is provided with the power to approve the application, or deny it.

For the procedure on submitting an application to request a modification, click here.

The purpose of placing compositional standards in a document IbR is not to reduce the health or safety of food products, or mislead consumers, but rather to keep pace with the changing landscape of food innovation.

As we mentioned above, we see this flexibility as a welcome approach. Even if product consultations have the potential to expose trade secrets to competitors without a guaranteed favourable result from a modification application, we appreciate the diplomacy in having multiple stakeholders weighing in on the need for revision, to ensure a level playing field.

Our greatest concerns lie with the efficiency of applying to the CFIA for a modification, and the length of time it may take to receive a response, as well as the efficiency in reviewing multiple documents IbR to assess compositional, labelling, and packaging compliance. We hope we are disproven in our concerns, though, as a flexible approach to food standards can only encourage market competitiveness and streamline the process to achieving variety.

We encourage any interested parties to engage with this consultation, as it promises to be imperative for the future of food regulation in Canada. Review the following website, read the discussion paper, and send your feedback to the CFIA.

The consultation closes September 22, 2023.

For assistance with food compositional reviews and/or label and packaging reviews, reach out to us at [email protected]

6 July 2023, 2:39 pm - Reduce, Reuse, Re-label: Environment and Climate Change Canada Release Consultation on Plastics

The Government of Canada has a broad goal of moving toward zero plastic waste. This goal includes requiring at least 50 percent recycled content in plastic packaging by 2030. Environment and Climate Change Canada (“ECCC”), the federal ministry charged with the recycling file, has released two consultations regarding a suite of measures it believes will make tangible progress towards these targets. The two relevant consultations are: the Recycled content and labelling rules for plastics: Regulatory Framework Paper and Technical paper: Federal Plastics Registry.

Recycled Content and Labelling Rules for Plastics: Proposed Regulations

The Government proposes to enact regulations using authorities under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (“CEPA”). The proposed regulations have three key elements focused on:

(1) Recycled content requirements

(2) Recyclability labelling rules

(3) Compostability labellingThese proposals are distinct, but related, and are detailed briefly below. To understand the proposals fully, we recommend reviewing the documents posted by ECCC on the Government of Canada website, which you can find here.

1: Minimum Recycled Content Requirements

The regulations propose mandating minimum levels of recycled post-consumer plastics in packaging. The objective of these rules is to regulate entities with the most control over the design and marketing of plastic packaging and single-use plastics. The proposed regulations would apply to both biobased plastics and conventional plastics, and packaging in this context refers to primary, secondary, and e-commerce packaging.

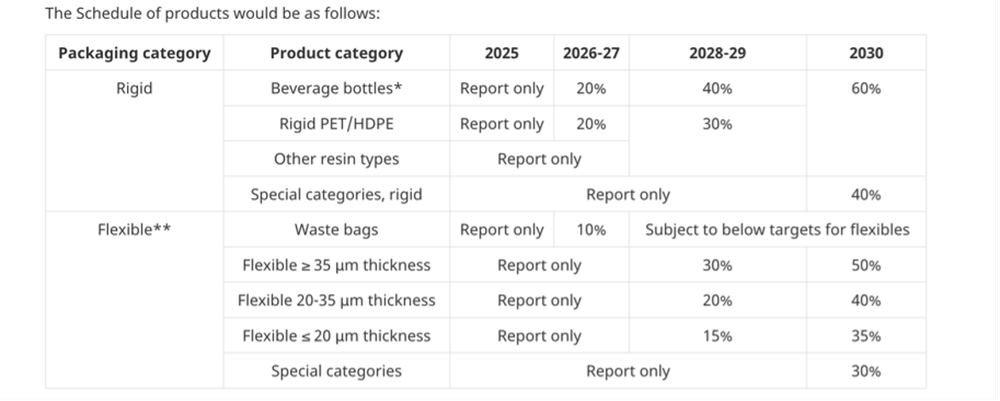

Plastic packaging is divided into rigid and flexible packaging, which are subject to specified minimum levels of recycled materials.

Exemptions to the content requirements include packaging that is waste, reusable packaging, tertiary or transport packaging (except for e-commerce), packaging intended for export to another country, or goods in transit. Small businesses, those with a gross revenue of under $5,000,000 or those who placed less than 10 tonnes of plastic packaging on the Canadian market in the previous year will also be exempt from the recycled content requirements.

The timeline for the transition to minimum recycling contents will begin in 2025.

(image from consultation document)

2: Recyclability Labelling Rules

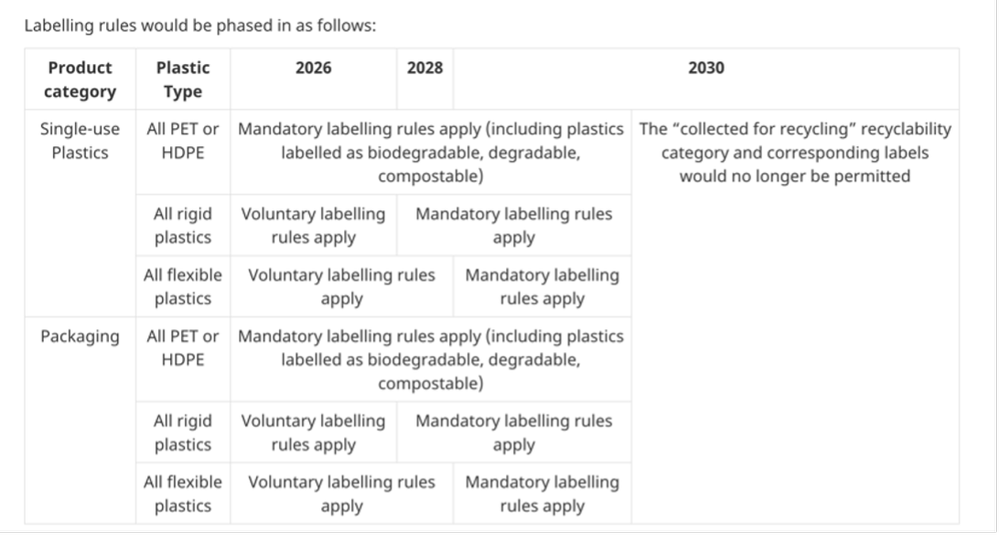

Recyclability labelling rules apply to consumer-facing primary and secondary plastic packaging, as well as single-use plastics. In short, the recyclability labelling rules require that accurate information is communicated to Canadian consumers about the recyclability of the product and instructions regarding how to properly dispose of the product.

Before placing an item on the market, regulated parties must assess their item against three recyclability criteria: collection, sorting and, re-processing. Once the regulated party has assessed each item for recyclability, the regulated party must categorize them based on the results as recyclable, non-recyclable, and collected. Based on the categorization, a regulated party would then need to add the correct label to the item. These labelling rules will revamp existing recyclability labelling. For example, the use of “chasing arrows” will be prohibited.

Exemptions to recyclability labelling rules are narrow and align broadly with food labeling rules outlined in the Food and Drug Regulations. Although labels are only required for plastics, regulated parties can choose to implement these elements for use on non-plastic packaging.

3: Compostability Labelling

Compostability labelling rules apply to consumer-facing primary and secondary plastic packaging, as well as single-use plastics.

Items labelled as “compostable” must be certified by an accredited third party to be an acceptable standard. Regulated parties are prohibited from labelling items with the term “degradable” or “biodegradable” or any form of those terms that implies the item will break down, fragment, or biodegrade in the environment. These items require a label of “non-recyclable”. No exemptions to compostability rules are currently proposed.

Compostability rules are intended to be phased in by 2030.

(image from consultation document)

Federal Plastics Registry

A federal plastics registry is intended to improve the Government’s knowledge of plastic waste, value recovery and pollution across Canada. The federal plastics registry would standardize the data that is collected on provincial and territorial Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) programs. From July to October 2022, the government received submissions on their consultation paper outlining the proposed approach to establishing a federal plastics registry. An updated version was released on April 18, 2023. To understand the Federal Plastics Registry proposal, we recommend reviewing the documents posted by ECCC on the Government of Canada website, which you can find here.

Parties, specifically provincial and territorial producers and federal producers will be obligated to report. Any businesses exempted under a provincial or territorial EPR policy will only need to report plastics placed on the market. The registry will require particular data points from producers of plastic products within each category. Data points include plastics collected for diversion, plastics successfully reused, and plastics sent to landfill.

The registry will provide data that is open and easily accessible to Canadians and will conform to the Directive on Open Government and the Directive on Service and Digital. Despite the open data, the registry should not compromise confidential information provided by producers.

Phase 1 reporting will begin on June 1, 2024.

Conclusion

Change is hard. While we expect that these changes will be perceived as threatening to operations, requiring drastic changes for certain industries, they’re also likely to be perceived as not aggressive enough by others. We generally view the proposed regulations as being aligned with an attempt by the developed world to reduce and recover plastic waste and encourage packaging alternatives. For example, as of January 1, 2023, new EU laws require brands that export to France and Italy to provide recycling information on all consumer product labels. We recommend that entities with experience in the French and Italian markets look to compliance efforts in those markets to better contextualize these changes.

Environment and Climate Change Canada intend to release finalized regulations regarding recycled content rules before the end of 2023.

Partners and stakeholders are invited to provide feedback on the Recycled content and labelling rules for plastics: regulatory framework paper and the Technical paper: Federal Plastics Registry by May 18, 2023. Feedback can be sent via mail or email to:

Tracey Spack, Director

Plastics Regulatory Affairs Division

351 Blvd Saint-Joseph

Gatineau, QC

K1A 0H3

[email protected]26 April 2023, 12:42 pm - Présentation de notre nouvel associé - Consolider nos services en français et l’expertise réglementaire canadienne

Chers clients, collègues et amis,

Nous sommes ravis d'annoncer l'arrivée de notre nouvel associé, Luc Bélanger. Cet ajout stratégique renforce non seulement l'expertise de notre équipe, mais nous permet également de mieux servir nos clients en leur offrant des services juridiques en français et en leur apportant une connaissance approfondie de la réglementation sur le marché canadien.

Luc apporte avec lui une riche expérience en droit réglementaire, ayant travaillé plus récemment en tant que président de la Commission de révision agricole du Canada, statuant sur les violations et les sanctions administratives pécuniaires entre les parties réglementées et l'Agence canadienne d'inspection des aliments, l'Agence des services frontaliers du Canada et l’Agence de réglementation de la lutte antiparasitaire. Sa spécialisation en droit réglementaire et administratif nous permet de mieux aider nos clients à naviguer dans le paysage réglementaire canadien complexe. De plus, Luc est membre du Barreau du Québec, ce qui nous permet d'améliorer notre communication et notre représentation pour nos clients francophones.

Avec Luc à bord, G. S. Jameson & Company est maintenant mieux positionné pour répondre aux divers besoins de nos clients, en assurant les normes les plus élevées de conseil juridique et de représentation. Nous sommes convaincus que la passion, le dévouement et l'expertise de Luc contribueront de manière significative au succès et à la croissance de notre cabinet au niveau national et international.

N'hésitez pas à contacter Luc pour toute assistance juridique ou demande de renseignements concernant les questions de réglementation canadienne.

Nous sommes impatients de continuer à vous servir grâce aux capacités accrues que Luc apporte à notre équipe.

13 April 2023, 6:57 pm - Introducing Our Newest Partner - Expanding Our Services in French and Canadian Regulatory Expertise

To our clients, colleagues, and friends:

We are thrilled to announce the addition of our newest partner, Luc Bélanger. This strategic addition not only strengthens our team's depth of expertise but also allows us to better serve our clients by offering legal services in French and providing extensive regulatory knowledge across the Canadian market.

Luc brings with him a wealth of experience in regulatory law, having worked most recently as chairperson of the Canada Agricultural Review Tribunal, adjudicating over violations and administrative monetary penalties between regulated parties and the Canadian Food Inspection, the Agency or Canada Border Services Agency and the Pest Management Regulatory Agency. His specialization in regulatory and administrative law enables us to better assist clients navigating the complex Canadian regulatory landscape. Additionally, Luc is called in Quebec and allowing us to enhance our communication and representation for our French-speaking clients.

With Luc on board, G. S. Jameson & Company is now better positioned to meet the diverse needs of our clients, ensuring the highest standards of legal counsel and representation. We are confident that Luc's passion, dedication, and expertise will contribute significantly to our firm's ongoing success and growth at the national and international level.

Please do not hesitate to reach out to Luc for any legal assistance or inquiries regarding Canadian regulatory matters.

We look forward to continuing to serve you with the expanded capabilities that Luc brings to our team.

13 April 2023, 6:56 pm - Canadian Cosmetic Regulations to Receive a Makeover

The Cosmetic Regulations, which exist under the Food and Drugs Act, came into force in 2006 and have not experienced a significant amendment since. The current regulations allow industry to label the cosmetic either by individually identifying the fragrance ingredient or using the term “parfum” at the end of the list of ingredients. For consumers with allergies or sensitivities, manufacturers aren’t required to provide much information to help guide them when trying to avoid products that may contain ingredients that could cause some form or reaction. Since the Cosmetic Regulations came into force, allergens and sensitivities are a much greater part of the daily lives of Canadians. While we often think about food allergens, there is now much greater awareness relating to cosmetic allergens.

Health Canada proposes to address the issue by updating the Cosmetic Regulations to disclose certain fragrance allergens on cosmetic labels. Under the proposed regulations, manufacturers will have the option to disclose ingredients on a website for cosmetics sold in small packaging. Health Canada acknowledges that this change will increase costs for industry but is seeking to balance those costs with increased informational transparency for those with sensitivities and allergies.

This is an initial consultation, so there’s some work to be done by stakeholders to help guide Health Canada. The proposed changes will impact the Food and Drugs Act in addition to the Cannabis Regulations under the Cannabis Act and the regulations are expected to come into force between six months and two years after consultation and regulatory publication.

Health Canada ask that interested stakeholders provide comments through the new online commenting feature in Canada Gazette, Part I by April 22, 2023. To provide your feedback on the proposed Regulations, use the commenting boxes provided on the webpage. Once you are satisfied with your comment, you can submit it directly to the Government of Canada through the Canada Gazette webpage.

For more information on compliance with the Food and Drugs Act and related regulations, please feel free to reach out to us at [email protected].

10 March 2023, 8:37 pm - Canada and Mexico Agree to Organic Equivalency

Mexico and Canada have signed a memorandum of understanding in relation to the equivalency of their organic standards this past week. From the Canadian perspective, Mexico is joining the US, UK, EU, Taiwan, Costa Rica, Japan, and Switzerland in becoming equivalent to the Canada Organic Regime. The Canada Mexico Organic Equivalency Arrangement relates to the following categories of products:

agricultural products of plant origin

processed foods of plant origin

livestock

processed food products containing livestock ingredients

beekeeping products

In January of 2020, I spoke with stakeholders in Mexico City who noted the failure of the two states to align on an organics standard: an essential and high value aspect in the produce market. Canada, with its limited growing season, represents a significant opportunity for Mexican agricultural stakeholders that produce high-value goods.

Organic standards are difficult for individual states to get their heads around in bilateral agreements. Ultimately, the consumer is at its most vulnerable when trying to determine the growing standards involved when comparing organic and conventional produce: it’s impossible for the consumer to tell the difference at retail.

So the wariness of governments when considering equivalency is informed by a few different concerns. Organic standards are specific to nations or regions – the Canadian standard is not the Mexican standard. Both are continually evolving, so neither organic standard is frozen in time. They’re also increasingly onerous and complex. This takes resources from both growers and government.

There are different manners of implementing organic standards. It makes a difference to governments whether organic growers are accredited using independent certification bodies or government or a blend of the two, and to what degree the certification group or government actually verifies compliance and enforces bad actors. That Canada has deemed the Mexicans to have created an organics process that bears equivalency to the Canada Organic Regime is a great accomplishment for Mexico. Accreditation under the Canadian Regime is no picnic.

At a more macro level, this equivalency agreement speaks to the relationship and trust between the two countries. Having worked together through complex and politically difficult issues during the USMCA/CUSMA/T-MEC negotiations, it’s heartening to see continued cooperation and integration between the three countries.

You can view the Canada Mexico Organic Equivalency Arrangement here.

19 February 2023, 6:20 pm - The Future of Milk Alternatives: Regulating Precision Fermented Plant-Based Beverages in Canada

Any trip that Canadians take to the grocery store reveals that plant-based alternatives to dairy milk have increased in popularity over recent years; what started with soy milk quickly grew into offerings as diverse as chickpea milk or oat milk. And while the public has swiftly adapted to plant-based products, the legal world continues to experience growing pains with the transition; complex, regulatory requirements for dairy labelling, as well as standards of identity, create challenges for anybody seeking to market milk alternatives.

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration led a public comment period in 2019 to determine if plant-based products should be allowed to utilize words like “milk” and “cheese” on their labels (here); while the majority of commentators found in favour of allowing dairy terminology on plant-based products, a percentage of lobbyists and Congress members, including committees, expressed concern. In January of 2022, the Food and Drug Administration commenced work on a draft guidance for labelling plant-based alternatives to milk and animal-derived foods; however, as of September 2022, the guidance remains under development.

In Canada, manufacturers of dairy alternatives experienced similar struggles to those in the United States (see “Vegan café defies CFIA order to stop using words burger, cheese”, published in 2019), but the plant-based market has made great strides in recent years. On the one hand, changes to the Food and Drug Regulations (“FDR”) now distinguish between simulated meat and poultry and other products which do not substitute for meat or poultry products; likewise, government agencies, such as Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, have produced policy reports on the sales figures of milk alternatives to track the growing popularity of plant-based foods. Between January 2018 and February 2021, 161 milk alternative beverages were launched in Canada; 264 were launched in the United States during that same period. Companies, such as Plant Veda, have received widespread news coverage of their assessment and licensure process, allowing them to distribute their milk alternatives across the country.

However, as the regulatory bodies make strides towards identifying and labelling plant-based alternatives in food, manufacturers of animal-free dairy milk have entered the market to stir the pot. In this new animal-free dairy universe, bright and catchy advertisements on TikTok and related social media lead the charge in advancing cellular agriculture to consumers who do not consume animal by-products or are lactose-intolerant, but may still enjoy the taste and nutritional benefits of dairy milk. And while these advertisements primarily exist for the American consumer, Canadians will likely see them, too. But what does this mean for the Canadian regulatory market?

In line with the idea of lab-grown meat, cellular agriculture has opened doors to create dairy-like products without animal by-products, through scientific innovation. The innovators are marketing the process as “real dairy that’s 100% animal-free”. To process the “dairy”, the innovators use cellular agriculture technology to add DNA sequences to food grade genetically engineered microflora, which then produces proteins and other ingredients naturally found in plants and animals. Whey protein, which is the prime protein produced, is transformed into a protein powder via fermentation and other similar processes, and then further supplemented with vitamins prior to sale. The result is a non-animal, protein powder that may be further blended with liquids to produce, what manufacturers describe as, animal-free dairy milk; the product claims to taste like dairy milk, too.

Does synthesizing some attributes traditionally found in milk, and making it taste similar, truly make the product dairy, though? In Canada, per the regulatory framework, it does not.

Dairy products in Canada are subject to the provisions of the Safe Food for Canadians Act (“SFCA”), Safe Food for Canadians Regulations (“SFCR”), the Food and Drugs Act (“FDA”), and the Food and Drug Regulations (“FDR”). Under this framework, Canada has laws for milk products, including dairy and milk standards and standards of identity, and guidance for advertising milk products.

In Canada, foods identified as “milk” must come from the mammary gland of a cow; this is a standard identified in the FDR. Dairy is defined in the SFCR as “milk or a food that is derived from milk, alone or combined with another food, and that contains no oil and no fat other than that of milk”. Based on these definitions it is impossible for a product derived from microflora, rather than a cow, to be dairy in Canada. Milk, on the other hand, is open for interpretation, as the CFIA allows a common name to be modified to show how a food deviates from its standard. This is the case for most plant-based, milk alternatives. Plant-based milk alternatives modify “milk” with the plant used to produce the alternative; coconut milk, for example, is an acceptable common name because it shows how the product deviates from the standard – a milk derived from coconuts rather than cows.

Canadian food laws also mandate that no person label, package, sell or advertise food that is false, misleading or deceptive or that creates an erroneous impression regarding its character, value, or composition. In this regard, while “animal-free dairy milk” modifies the common names of “dairy” and “milk” to show a deviation, the negative claim of “animal-free” does not lend itself to the correct composition of the product, and could even be seen as confusing or misleading. The product may be animal-free, but what is it made of? The product may be a “milk”, but can it be animal-free dairy?

And then there is the issue of supplementing a milk alternative with vitamins; under Canada’s new, regulatory framework for supplemented foods, an “animal-free dairy milk” would be considered a supplemented food and thus beholden to additional labelling requirements, such as a Supplemented Food Facts table (“SFFt”), a food caution identifier, and a caution box. While not overly cumbersome, these requirements present another regulatory hurdle for companies attempting to market milk alternatives in Canada.

Thus, while Canadian regulators may have their eyes on cellular agriculture to monitor the future of food, our food laws – as they currently exist – present many obstacles to achieving this sort of scientific advancement. The rise in popularity of plant-based alternatives to animal foods will continue to encourage changes to food laws; likewise, as cellular agriculture grows in interest, Canadian regulators must confront its existence to determine how best to accommodate it. Innovators always face the greatest challenges, but change arises only if somebody challenges the status quo.

If you require assistance with your labelling, packaging, or marketing, or would like help with submitting a novel foods application to Health Canada, feel free to reach out to us at [email protected]

3 February 2023, 5:10 pm - GSJ&Co's Annual Review of Food Law in Canada

Each year at G. S. Jameson & Company, we develop a video where we try to capture the most significant developments to food regulation that are happening in Canada. The hope is that our Canadian and international friends can take a lunch break to learn enough to do some issue spotting for their clients, employer, students, or simply to keep their knowledge up to date.

In 2022, there were an overwhelming number of changes to the Canadian marketplace that either were implemented or are going to happen soon. For what it's worth, we probably say that every year. But this year, it certainly feels true.

Many thanks to all of our clients and friends, who encourage us to do this each year. And many thanks to Julia Witmer and Curry Leaman for bringing this great annual project to life.12 January 2023, 3:57 am - For Ontario Charities and Not-for-Profits, it's time to move to a new Act

Food charities make up some of Canada’s oldest not-for-profits. These charities continue to play an integral part in Canada’s public support architecture. In our experience working and volunteering with food charities, the operations on the ground are wholly consuming: staff, management and directors are passionate about pursuing the charitable purposes of the organization. At times, non-operational aspects of some charities can end up shuffled down the agenda at board meetings, for better or worse.

It is for those organizations in Ontario, food focused or not, who we write to in this blog post. We want to tell food charities and not-for-profits that they likely have positive legal obligations to move their corporation from old legislation to new. Perhaps in a more positive vein, this transition – called a “continuance” – offers Ontario charities and not for profits the opportunity to re-evaluate how they engage with members and other key stakeholders. It’s a time to turn an organization’s mind to the question of whether it is structured appropriately to ensure compliance with Ontario’s regulations and engagement with its community.

The Ontario Not-for-Profit Corporations Act, 2010

The Ontario Not-for-Profit Corporations Act, 2010 (“ONCA”) came into force on October 18, 2021, replacing the previous Ontario Corporations Act (“OCA”). Every not-for-profit in Ontario is required to amend their existing articles through the process of continuance to comply with ONCA by October 18, 2024.

ONCA ushers in a new era for not-for-profits. It is designed to allow not-for-profit corporations to function more like a traditional business corporation. In many ways it follows a similar structure to the Canada Not-for-Profit Corporations Act which came into force on June 23, 2010, and regulates federal not-for-profit corporations.

Key Changes Under ONCA

Although ONCA continues to operate with members, rather than shareholders, ONCA provides additional rights to these members that resemble those of shareholders. Significantly more information is contained in the articles rather than by-laws, and there are clear majorities and thresholds set forth in ONCA. A hallmark of OCA not-for-profits and charities was that the corporation was, to a large degree, simply left to the members and directors to set out in their by-laws. By comparison, ONCA is far more prescriptive. Other key features of ONCA, include: the transition from the term “letters patent” to the term “articles of incorporation”, the ability for not-for profits to have purposes in their articles which are commercial in nature, and the requirement of a minimum of three directors who do not need to be members, unless the by-laws state otherwise.

Considerations for Not-for-Profits: Membership

These enhanced membership rights mean that members have rights under ONCA which need to be considered in relation to the purposes of the organization. Accordingly, from a process perspective, reviewing membership class terms should be done before amending the corporation to fit with ONCA. If you are creating more than one class of membership, these classes and their voting rights must be outlined in the articles. The by-laws will document the additional conditions required for membership.

Not-for-profits can create one, or two or more different classes of membership with varying conditions of membership. Common not-for-profit membership categories include:

1. Closed Membership: The directors and members are the same individuals. Other participants can be referred to as a non-membership category, like affiliates, associates, supporters, or congregants.

2. Open Membership: Anyone who supports your not-for-profit’s vision, mission, and values can become a member.

3. Semi-Open/ Conditional Membership: Conditions of membership can be outlined in the bylaws. For example, bylaws can specify who can become a member, how they can become a member, what code of conduct they must follow to stay a member, and the maximum number of members. The conditions of membership cannot take away the rights that members have under ONCA (for example voting right if there is only one class).

4. Self-Perpetuating Membership: Directors don’t have to be members under ONCA. However, bylaws can say that directors will be the only members. This structure is called “self-perpetuating” because the directors, acting as members, elect all new directors.

5. Hybrid Membership: The directors are your only voting members, and a non-voting class is open to anyone who supports your not-for-profit’s work.

6. Representative Membership: The directors make up one class of voting members. Also have one or more other voting classes made up of members who are elected by and represent different types of stakeholders.

Other Considerations for Not-for-Profits

Although not-for-profits are not required to pass new bylaws to conform with the new Act, strategically it makes sense to ensure your articles and bylaws align with your organization’s vision and mission at the same time as engaging in the continuance process. These changes may include amendments to both the articles of incorporation and the by-laws themselves.

There are a variety of other small and fundamental changes between the OCA and ONCA. We recommend for all not-for-profits to meet with a lawyer to discuss how this transition will directly impact their corporation. If you are a food not-for-profit in Ontario, ONCA will apply to you. The continuance involves various steps and drafting of some documents to transfer the corporation to ONCA. If you require advice and support regarding the transition to ONCA, please contact us at [email protected].

29 December 2022, 10:52 pm - More Episodes? Get the App

Your feedback is valuable to us. Should you encounter any bugs, glitches, lack of functionality or other problems, please email us on [email protected] or join Moon.FM Telegram Group where you can talk directly to the dev team who are happy to answer any queries.

Building NewLaw

Building NewLaw

Podcast - Ideablawg

Podcast - Ideablawg

Borderlines

Borderlines

Hull on Estates

Hull on Estates

Blaneys Podcast

Blaneys Podcast

Lawyered

Lawyered