History of the Earth

Richard I. Gibson

Earth's Geological History in chronological order

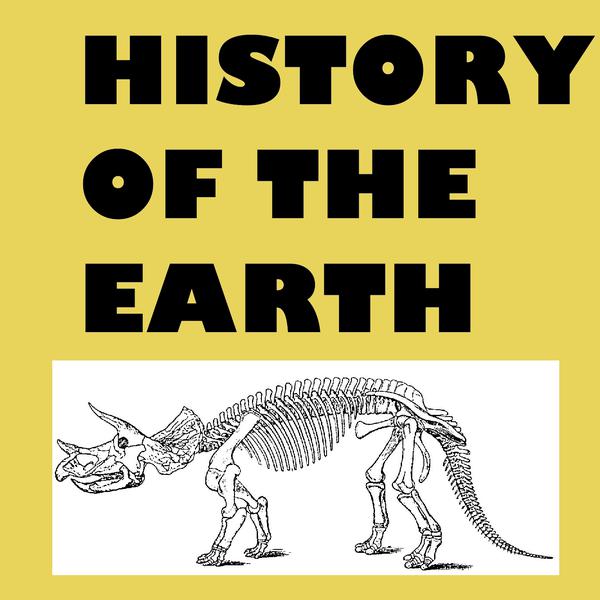

- Cone-in-Cone

The mineral here is just calcite (even though it’s mostly almost black), but it shows interesting features. Cone-in-cone structures are nested cones, seen here in cross section. The inset shows them a little better – in the main photo, they are represented by very narrow vertical triangles.

It’s not certain how these things form, but some kind of systematic displacement because of microscopic crystal growth variations is probably the favored idea. The variations might be because of clay content (which in my specimen might help account for the dark color), or because of changes in volume when aragonite (chemically identical to calcite, calcium carbonate, but a different crystal structure with a different volume) changes to calcite which can happen during diagenesis, the process of sediment solidifying to rock.

Cone-in-cone might also result from pressure variations, either before or after the rock becomes solid. Pressure variations that might depend on the clay content could produce micro-fractures in the calcite that make the individual crystalline material slide consistently to make the cones. This more structural interpretation might be supported by the fact that my specimens are from a seam of calcite about 3 or 4 inches thick that was within thicker, stronger rocks.

Bottom line, the features are caused by some kind of microcrystalline displacement, but exactly how this happens is not settled.

This specimen is from near White Sulphur Springs, Montana. Collected in 2004.

Link: Cone-in-Cone on Wikipedia

—Richard I. Gibson30 May 2019, 4:31 pm - The Llanite Dike

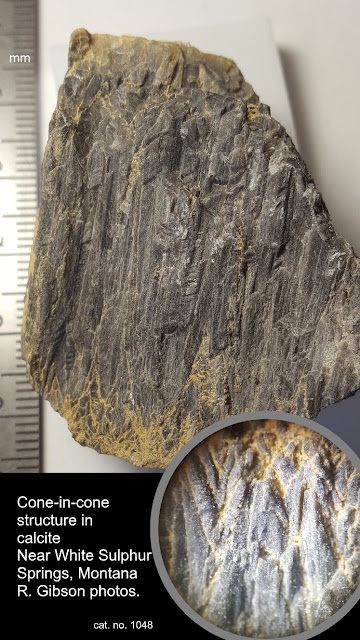

Mineral Monday + Tectonic Tuesday. Blue quartz is uncommon and is usually

colored by inclusions of unusual minerals like crocidolite, tourmaline, or

dumortierite. The purplish-blue quartz here, from north of Llano, Texas, is

colored by inclusions of ilmenite (iron-titanium oxide). This rock is called

llanite for its occurrence in the Llano Uplift of central Texas, and although

similar rocks are found in other parts of the world, the variety name llanite

really only applies to this location. On a sunny day, the blue quartz in the

rocks has an opalescent sheen that sometimes seems to “wink” at you from the outcrop.

Mineral Monday + Tectonic Tuesday. Blue quartz is uncommon and is usually

colored by inclusions of unusual minerals like crocidolite, tourmaline, or

dumortierite. The purplish-blue quartz here, from north of Llano, Texas, is

colored by inclusions of ilmenite (iron-titanium oxide). This rock is called

llanite for its occurrence in the Llano Uplift of central Texas, and although

similar rocks are found in other parts of the world, the variety name llanite

really only applies to this location. On a sunny day, the blue quartz in the

rocks has an opalescent sheen that sometimes seems to “wink” at you from the outcrop.

More generally, the rock is a rhyolite porphyry – rhyolite meaning pretty high in silica (a granite-like composition) and formed at or near the surface of the earth, and porphyry meaning it has two grain sizes – a fine matrix, with larger crystals of quartz (and microcline feldspar) suspended in that matrix. This implies that there were two periods of cooling, one at deeper depths where it took the larger crystals a longer time to cool (and grow), followed by a later, quicker period of cooling, so the matrix crystallized so fast the grains are very small, but the larger, older grains are still there within the matrix.

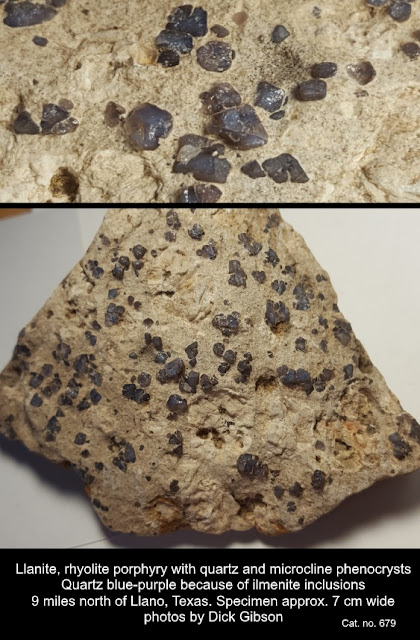

All that cooling happened about 1,093,000,000 years ago (almost 1.1 billion) during a time called the Grenville Orogeny (orogeny means mountain-building) when what is now central Texas was amalgamated to the main part of the North American continent. The llanite was probably an aspect of the intrusions of the Town Mountain Granite, which has similar age but crystallized at greater depth. It’s part of a long belt that extends with some discontinuity to central Tennessee, through Kentucky and Ohio, then northeast across Ontario, Quebec, and into Labrador. Rocks now in southern Scandinavia were part of the Grenville mountain belt, the result of a collision between continental masses that was assembling the supercontinent Rodinia over a long period of time, from about 1,250 million years ago to 980 million years ago.

The llanite, in the form of a narrow dike, intruded older

rocks toward the end of the Grenville Orogeny. The mountain belt continued into

Mexico, and rocks of similar age are found in Australia and Antarctica as well

as South America today. Exactly how those rocks fit into the big picture is

still debated, but one version of the assembled continent of Rodinia is in the

comments.

The llanite, in the form of a narrow dike, intruded older

rocks toward the end of the Grenville Orogeny. The mountain belt continued into

Mexico, and rocks of similar age are found in Australia and Antarctica as well

as South America today. Exactly how those rocks fit into the big picture is

still debated, but one version of the assembled continent of Rodinia is in the

comments.

At left, one reconstruction (others exist) of Rodinia about 750 million years ago, just before it began to break up. “Rodinia” is from Russian for “motherand,” or “to give birth,” alluding to this continent’s early place in the rifting-collision cycles (called Wilson Cycles with respect to ocean basins, for J. Tuzo Wilson) that have followed. Even so, Rodinia was probably preceded by at least one earlier supercontinent, named Columbia – but that’s debated.

The llanite dike intrudes older Precambrian metamorphic rocks called the Valley Spring Gneiss, which have a lot of magnetite in them. The Valley Spring Gneiss is dated to about 1,375,000,000 years ago or older.

The phenocrysts (“showing” or “visible” crystals) of blue

quartz in the llanite are supposed to be “beta quartz,” a high-temperature,

higher symmetry form of quartz that can crystallize only above 573ºC – in fact,

it cannot even exist at surface conditions and pressures, so all “beta quartz”

is actually a pseudomorph (“false form”) of regular quartz that has formed as

the original beta quartz cooled. This little crystal (not from Llano) is probably

one such pseudomorph. (Technically, since I knew you wanted even more jargon,

it’s a paramorph rather than a pseudomorph, because while the crystal structure

has changed, the chemistry has not.) The essentially perfect hexagonal symmetry

of this crystal marks it as a beta-quartz shape, versus the lower (trigonal)

uneven symmetry typically displayed by normal quartz. It’s possible for normal

trigonal quartz to have equally developed faces that appear fully hexagonal,

but it’s unusual.

27 May 2019, 1:09 pm

The phenocrysts (“showing” or “visible” crystals) of blue

quartz in the llanite are supposed to be “beta quartz,” a high-temperature,

higher symmetry form of quartz that can crystallize only above 573ºC – in fact,

it cannot even exist at surface conditions and pressures, so all “beta quartz”

is actually a pseudomorph (“false form”) of regular quartz that has formed as

the original beta quartz cooled. This little crystal (not from Llano) is probably

one such pseudomorph. (Technically, since I knew you wanted even more jargon,

it’s a paramorph rather than a pseudomorph, because while the crystal structure

has changed, the chemistry has not.) The essentially perfect hexagonal symmetry

of this crystal marks it as a beta-quartz shape, versus the lower (trigonal)

uneven symmetry typically displayed by normal quartz. It’s possible for normal

trigonal quartz to have equally developed faces that appear fully hexagonal,

but it’s unusual.

27 May 2019, 1:09 pm - History of Geology: Recognizing overthrusts

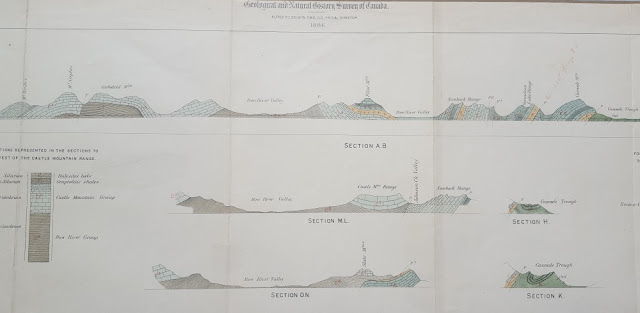

Middle section of the 38-inch cross-section

Middle section of the 38-inch cross-section

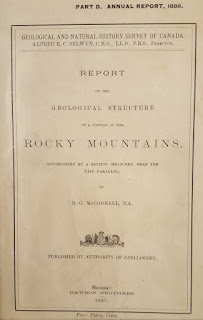

Cover

This Tectonic Tuesday is also an example of the History of Geology.

“The thrust producing these crustal movements and dislocations came from the west, and must have been highly energetic in its action, as some of the breaks are of huge proportions, and are accompanied by displacements of many thousands of feet. The faulted region is now about twenty-five miles wide, but a rough estimate places its original width at over fifty miles, the difference indicating the amount of compression is has suffered.”

With these words, R. G. McConnell was the first geologist to report the interpretation of low-angle thrust faults with significant throw in the western Cordillera of North America. McConnell’s study, entitled “Report on the Geological Structure of a portion of the Rocky Mountains,” was published in 1887 by the Geological and Natural History Survey of Canada. These cross-sections, near the 51st Parallel, accompanied the report. They document work during the field season of 1886, which was primarily spent in compiling a general geologic section along the line of the Canadian Pacific Railway.

The section begins on the right at Devil’s Gap, east of Devil’s Lake (now Lake Minnewanka) and extends westward toward Banff. Cascade Mountain, labeled on the section, is just north of Banff and rises to 9836 feet above sea level. The profile then approximately follows the railway up the valley of the Bow River, past Laggan (now the community of Lake Louise), and over the Continental Divide at Kicking Horse Pass. Cathedral Mountain (10,464 ft) and Mount Stephen, shown on the section, are just west of Kicking Horse Pass. The Burgess Shale, classic locality for soft-bodied Cambrian fossils, was discovered in 1909 by Chares D. Wolcott about three miles north of the summit of Mt. Stephen.

Cover

This Tectonic Tuesday is also an example of the History of Geology.

“The thrust producing these crustal movements and dislocations came from the west, and must have been highly energetic in its action, as some of the breaks are of huge proportions, and are accompanied by displacements of many thousands of feet. The faulted region is now about twenty-five miles wide, but a rough estimate places its original width at over fifty miles, the difference indicating the amount of compression is has suffered.”

With these words, R. G. McConnell was the first geologist to report the interpretation of low-angle thrust faults with significant throw in the western Cordillera of North America. McConnell’s study, entitled “Report on the Geological Structure of a portion of the Rocky Mountains,” was published in 1887 by the Geological and Natural History Survey of Canada. These cross-sections, near the 51st Parallel, accompanied the report. They document work during the field season of 1886, which was primarily spent in compiling a general geologic section along the line of the Canadian Pacific Railway.

The section begins on the right at Devil’s Gap, east of Devil’s Lake (now Lake Minnewanka) and extends westward toward Banff. Cascade Mountain, labeled on the section, is just north of Banff and rises to 9836 feet above sea level. The profile then approximately follows the railway up the valley of the Bow River, past Laggan (now the community of Lake Louise), and over the Continental Divide at Kicking Horse Pass. Cathedral Mountain (10,464 ft) and Mount Stephen, shown on the section, are just west of Kicking Horse Pass. The Burgess Shale, classic locality for soft-bodied Cambrian fossils, was discovered in 1909 by Chares D. Wolcott about three miles north of the summit of Mt. Stephen.

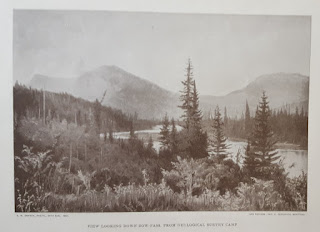

Frontispiece

When later geologists defined the continuity of individual thrust faults in the Canadian Rockies, one of the major thrusts was named for McConnell. The photo of the Geological Survey Camp, used as the frontispiece of this report, was actually taken during Dawson’s surveys a few years later. Dawson’s work was generally in country to the south of that described by McConnell.

When I found this report in a used book store, it was falling apart – covers off, pages torn, and the edges of the loose, folded cross-section were severely damaged. Unfolded, the plate with the cross-sections is 10”x38” and it is hand-colored. The plate is shown below.

Frontispiece

When later geologists defined the continuity of individual thrust faults in the Canadian Rockies, one of the major thrusts was named for McConnell. The photo of the Geological Survey Camp, used as the frontispiece of this report, was actually taken during Dawson’s surveys a few years later. Dawson’s work was generally in country to the south of that described by McConnell.

When I found this report in a used book store, it was falling apart – covers off, pages torn, and the edges of the loose, folded cross-section were severely damaged. Unfolded, the plate with the cross-sections is 10”x38” and it is hand-colored. The plate is shown below.

Entire plate

21 May 2019, 8:58 pm

Entire plate

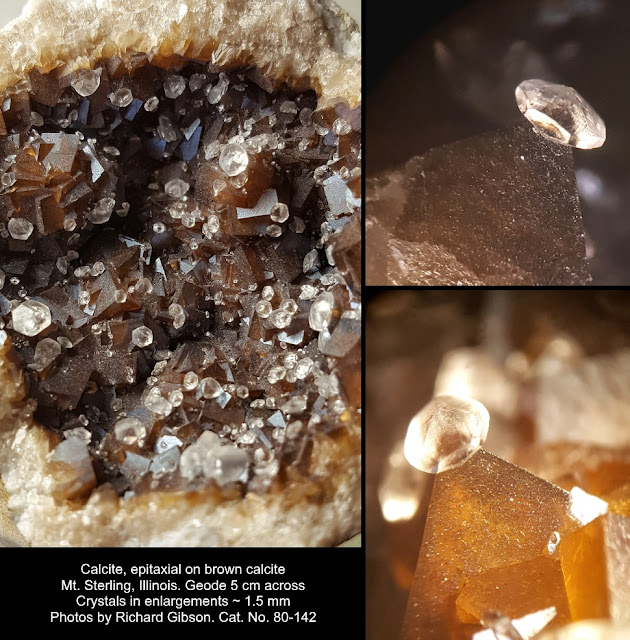

21 May 2019, 8:58 pm - Epitaxy

Epitaxy, from Greek words meaning “upon” or “above” and “ordered arrangement,” in minerals means crystals of one (or the same) mineral growing in a particular crystallographic position on another (or the same) mineral. It happens because the molecular spacings and orientations happen to be similar, allowing, even encouraging the crystal structure of the second, later mineral to mesh with that of the first. Some mineralogists might say that epitaxy requires the two minerals to be different minerals, but I do not – just two distinct generations of crystallization.

My example here is calcite, calcium carbonate – the sharp brown crystals are rhombohedrons, and the stuff is probably brown because it may be slightly iron-bearing (but it’s not siderite, iron carbonate). The clear crystals sit preferentially upon the corners of the rhombohedrons. I’m pretty sure, but because calcite makes a myriad of crystal forms I’m not certain, that the rhombohedral corner of the brown crystals represents the basal pinacoid position in those crystals, and the complex saucer-like colorless second-generation crystals are poised there on their own basal pinacoids. The two pinacoid surfaces have the same molecular geometry, so the two different generations of crystals – brown and colorless – joined there.

The colorless crystals show a bunch of different forms, prisms, rhombohedrons, and probable scalenohedrons, along with the likely pinacoids.

This is all in a geode about 5 centimeters across, from Mt. Sterling, Illinois. The little crystals in the photo enlargements are about 1.5 millimeters across. I actually have both halves of this geode, although they were acquired from different dealers at different mineral shows a year or so apart.

Epitaxy isn’t especially unusual in the mineral world, but unless the minerals are in a particular crystallographic orientation, we’d probably just call one mineral growing on another an encrustation, or overgrowths or some similar word.

—Richard I. Gibson19 May 2019, 7:25 pm - An extension of the Mid-Continent Rift?

In the far northwest corner of the flat, flat Texas panhandle, extending into New Mexico, there’s a narrow, elongate magnetic low. The intensity of the anomaly – 250 nanoTesla or more – says it’s fundamentally the expression of a lithologic change rather than a structure; i.e. it represents something pretty strongly magnetic. Its long narrow geometry is that of a dike. And its negative value suggests that it’s reversely polarized, solidifying from magma during a time when the earth’s magnetic field was in the orientation opposite to that today.

All that is interesting, I guess, but the thing has much broader implications. If it is a dike – which is likely in my opinion – that suggests that it formed at a time when extension, pulling apart, was the dominant stress in this area. Dikes can form under compression, but it’s a lot easier for them to intrude if the rocks are pulling apart, opening up cracks into which magma can force itself.

The northeast-southwest orientation is also intriguing, because it points pretty much dead on at a possible branch of the Mid-Continent Rift, a pull-apart feature that runs from Kansas through southeast Nebraska, northeast across Iowa, up into Minnesota, and into Lake Superior. It’s a 1.1-billion-year-old break in North America – a break that failed to completely dismember the continent, but just formed a long narrow trough filled in many places with dense, magnetic basalt. Kind of like the Red Sea today, but not as linear.

This dike in the Texas panhandle isn’t trivial – it’s at least 45 miles (70 kilometers) long. There are additional similar features on trend with it in Kansas. My interpretation is that it represents a far away expression of the extension and intrusion related to the Mid-Continent Rift System. This possible relationship is shown in a map below.

The depth to these rocks in the panhandle is probably only 3500 or 4000 feet, but to my knowledge there is no drilling to those depths in this area, so we don’t actually have rocks to validate this interpretation. But I’d bet a beer that you’d find a reversely polarized dike of basalt or similar lithology, containing a decent amount of magnetite, that solidified around 1.1 billion years ago.

In the far northwest corner of the flat, flat Texas panhandle, extending into New Mexico, there’s a narrow, elongate magnetic low. The intensity of the anomaly – 250 nanoTesla or more – says it’s fundamentally the expression of a lithologic change rather than a structure; i.e. it represents something pretty strongly magnetic. Its long narrow geometry is that of a dike. And its negative value suggests that it’s reversely polarized, solidifying from magma during a time when the earth’s magnetic field was in the orientation opposite to that today.

All that is interesting, I guess, but the thing has much broader implications. If it is a dike – which is likely in my opinion – that suggests that it formed at a time when extension, pulling apart, was the dominant stress in this area. Dikes can form under compression, but it’s a lot easier for them to intrude if the rocks are pulling apart, opening up cracks into which magma can force itself.

The northeast-southwest orientation is also intriguing, because it points pretty much dead on at a possible branch of the Mid-Continent Rift, a pull-apart feature that runs from Kansas through southeast Nebraska, northeast across Iowa, up into Minnesota, and into Lake Superior. It’s a 1.1-billion-year-old break in North America – a break that failed to completely dismember the continent, but just formed a long narrow trough filled in many places with dense, magnetic basalt. Kind of like the Red Sea today, but not as linear.

This dike in the Texas panhandle isn’t trivial – it’s at least 45 miles (70 kilometers) long. There are additional similar features on trend with it in Kansas. My interpretation is that it represents a far away expression of the extension and intrusion related to the Mid-Continent Rift System. This possible relationship is shown in a map below.

The depth to these rocks in the panhandle is probably only 3500 or 4000 feet, but to my knowledge there is no drilling to those depths in this area, so we don’t actually have rocks to validate this interpretation. But I’d bet a beer that you’d find a reversely polarized dike of basalt or similar lithology, containing a decent amount of magnetite, that solidified around 1.1 billion years ago.

—Richard I. Gibson

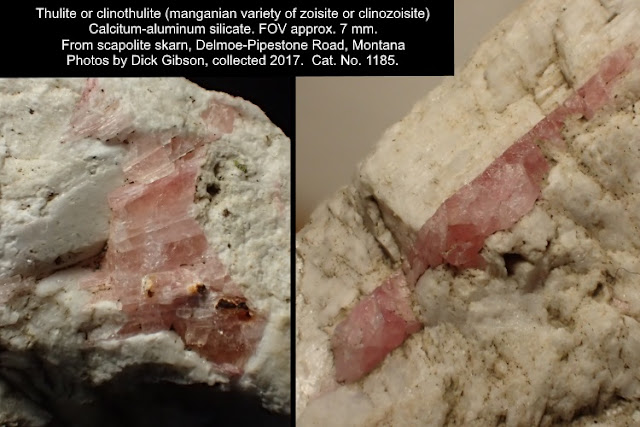

17 May 2019, 6:39 pm - Thulite

Thule was the far north in Greek and Roman literature, often identified with Scandinavia. Thursday was named after Thor, the Norse god of thunder. Whether these pink minerals are orthorhombic thulite or monoclinic clinothulite would take analysis that I haven’t done, but either way they contain trivalent manganese to give the pink color.

The white mineral that contains them is scapolite, specifically meionite (I HAVE had an x-ray analysis of it), a different calcium-aluminum silicate. The outcrop, a couple miles up the Delmoe Road from the Pipestone exit, is mostly scapolite, in a zone that is the continuation of the boundary between the Butte and Rader Creek Plutons of the Boulder Batholith.15 May 2019, 2:35 pm - 150 years of the Periodic table

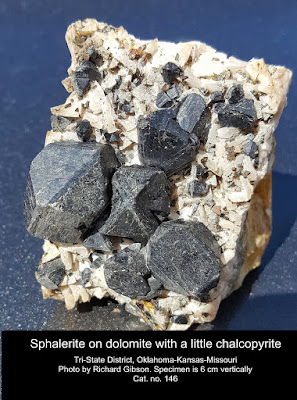

2019 marks the sesquicentennial of Dmitri Mendeleev’s Periodic Table of the elements, which was not just an effective organizational scheme based on the atomic nature of the elements, but also a predictive tool regarding elements that had not yet been discovered in 1869.

The validity of the Table was proven in 1875. Mendeleev had predicted the existence of several elements, including one he called eka-aluminum. “Eka” is Sanskrit for “one,” thus meaning the unknown element would be one period down from aluminum. French chemist Paul Emile Lecoq de Boisbaudran identified a new element spectroscopically (as Mendeleev had foretold) in a sample of the mineral sphalerite (zinc sulfide). He named Element 31 gallium for his native France (Gallia in Latin) in 1875.

Mendeleev’s predictive table even allowed him to estimate properties of the unknown elements. When de Boisbaudran reported eka-aluminum/gallium’s density as 4.7 grams per cubic centimeter, Mendeleev suggested to him that he should recalculate it. When the new measurement was made, gallium’s density was found to be 5.9 g/cc, almost exactly as Mendeleev predicted several years earlier on theoretical grounds alone. Today the density of gallium is taken as 5.904 g/cc.

As described in my book What Things Are Made Of, gallium is used in tiny but critical amounts in solid-state semi-conductors in lots of high-tech devices, from computers and radios to cell phones and televisions. Gallium also finds its way into wireless technology infrastructure, integrated circuits, LED manufacture, and solar cells.

As it was when it was discovered, gallium today is found mostly in zinc and aluminum minerals and is produced by refining those ores, which are dominantly sphalerite for zinc and bauxite for aluminum. There’s typically only 50 parts per million or less gallium in such ores, but refineries can often separate it economically. In terms of crustal abundance, gallium is about the same as lead – but while lead easily forms common minerals that can be exploited economically, gallium’s properties mean that the few minerals it forms are extraordinarily rare. Instead, gallium gets incorporated into the structures of those zinc and aluminum compounds.

The United States is 100% dependent on imports for gallium, mainly from China (32%), United Kingdom (28%), Germany (15%) and Ukraine (14%). China is overwhelmingly the 600-pound-gorilla in terms of gallium, with more than 95% of total world production.

The sphalerite in this photo probably has some gallium in it, a few molecules at least, but I haven’t had it analyzed. The mineralization is hosted in limestones and cherty rocks of Mississippian age, deposited about 345 million years ago. The mineralization came in at some later time.

2019 marks the sesquicentennial of Dmitri Mendeleev’s Periodic Table of the elements, which was not just an effective organizational scheme based on the atomic nature of the elements, but also a predictive tool regarding elements that had not yet been discovered in 1869.

The validity of the Table was proven in 1875. Mendeleev had predicted the existence of several elements, including one he called eka-aluminum. “Eka” is Sanskrit for “one,” thus meaning the unknown element would be one period down from aluminum. French chemist Paul Emile Lecoq de Boisbaudran identified a new element spectroscopically (as Mendeleev had foretold) in a sample of the mineral sphalerite (zinc sulfide). He named Element 31 gallium for his native France (Gallia in Latin) in 1875.

Mendeleev’s predictive table even allowed him to estimate properties of the unknown elements. When de Boisbaudran reported eka-aluminum/gallium’s density as 4.7 grams per cubic centimeter, Mendeleev suggested to him that he should recalculate it. When the new measurement was made, gallium’s density was found to be 5.9 g/cc, almost exactly as Mendeleev predicted several years earlier on theoretical grounds alone. Today the density of gallium is taken as 5.904 g/cc.

As described in my book What Things Are Made Of, gallium is used in tiny but critical amounts in solid-state semi-conductors in lots of high-tech devices, from computers and radios to cell phones and televisions. Gallium also finds its way into wireless technology infrastructure, integrated circuits, LED manufacture, and solar cells.

As it was when it was discovered, gallium today is found mostly in zinc and aluminum minerals and is produced by refining those ores, which are dominantly sphalerite for zinc and bauxite for aluminum. There’s typically only 50 parts per million or less gallium in such ores, but refineries can often separate it economically. In terms of crustal abundance, gallium is about the same as lead – but while lead easily forms common minerals that can be exploited economically, gallium’s properties mean that the few minerals it forms are extraordinarily rare. Instead, gallium gets incorporated into the structures of those zinc and aluminum compounds.

The United States is 100% dependent on imports for gallium, mainly from China (32%), United Kingdom (28%), Germany (15%) and Ukraine (14%). China is overwhelmingly the 600-pound-gorilla in terms of gallium, with more than 95% of total world production.

The sphalerite in this photo probably has some gallium in it, a few molecules at least, but I haven’t had it analyzed. The mineralization is hosted in limestones and cherty rocks of Mississippian age, deposited about 345 million years ago. The mineralization came in at some later time.

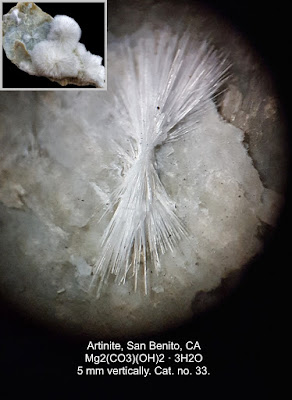

—Richard I. Gibson14 May 2019, 2:32 pm - Artinite and the Coast Ranges of California

The mineral is artinite, a magnesium carbonate that is an

alteration product of high-magnesium serpentinites of the Diablo Range in

central California. It’s from New Idria, a mercury (and other) mining district

named for the historic Idria mercury mines now in Slovenia, which have been

mined since 1490.

The mineral is artinite, a magnesium carbonate that is an

alteration product of high-magnesium serpentinites of the Diablo Range in

central California. It’s from New Idria, a mercury (and other) mining district

named for the historic Idria mercury mines now in Slovenia, which have been

mined since 1490.

Tectonically, the New Idria area of California is in a fenster (German for window), a hole in a thrust sheet that is related to the collisions that produced the California Coast Ranges. Serpentine’s mechanical properties are such that it can flow – very slowly on human scales – and in places like Mt. Diablo and New Idria, it has risen buoyantly like a salt dome to breach the thrust sheet and bring the underlying serpentine to the surface.

The magnesium-rich serpentinite is part of the Coast Range Ophiolite – a word meaning “snake rock” for its often greenish color and scaly texture. Ophiolites are usually bits of oceanic crust that have been emplaced within or upon continental crust, and that’s what happened here.13 May 2019, 4:49 pm - FuchsiteFuchsite is a chromium-bearing variety of the mica muscovite, K(Al,Cr)3Si3O10(OH)2 . Chromium gives the green color to the muscovite.

This specimen was collected by Theresa Schwartz and given to

me by Susan Vuke. Theresa reports it was a clast in a pediment near Little

Antelope Valley, northwest of Harrison, Montana. That leaves the question open

as to where it formed and came from, but a source in the Tobacco Root Mountains

is most likely. The pediment gravel itself was probably deposited fairly

recently, the last 50 million years or so, a result of the uplift of the

Tobacco Roots. There are at least two chromite occurrences regionally nearby, 3

miles southwest of Silver Star (in the Highlands Mountains), and 5 miles

southeast of Sheridan (southwestern Tobacco Roots) (Chadwick, 1941 Montana Tech

thesis).

This specimen was collected by Theresa Schwartz and given to

me by Susan Vuke. Theresa reports it was a clast in a pediment near Little

Antelope Valley, northwest of Harrison, Montana. That leaves the question open

as to where it formed and came from, but a source in the Tobacco Root Mountains

is most likely. The pediment gravel itself was probably deposited fairly

recently, the last 50 million years or so, a result of the uplift of the

Tobacco Roots. There are at least two chromite occurrences regionally nearby, 3

miles southwest of Silver Star (in the Highlands Mountains), and 5 miles

southeast of Sheridan (southwestern Tobacco Roots) (Chadwick, 1941 Montana Tech

thesis).

A reasonable idea for the protolith is a well-sorted, clean, quartz sandstone, with a very few resistant detrital chromite grains that during metamorphism had the chromium mobilized to find potassium and aluminum impurities from wherever you want to form the mica. The chromite could have come (with obvious challenges and difficulty) from the Stillwater Complex, the chromite- and platinum-rich ultramafic deposit on the north flank of the Beartooth Mountains, supposing some fluvial system to transport the sand that became this quartzite. That could have been a Precambrian river system, eroding either from what is now the Beartooths to the east or from the minor chromite occurrences to the west.

Fuchsite was named in 1842 by Karl F. Emil von Schafhäutl in honor of Johann Nepomuk von Fuchs [May 15, 1774 Mattenzell, near Bremberg, Lower Bavaria, Germany - March 5, 1856 Munich, Germany] professor of chemistry and mineralogy at University of Landshut and curator of the mineralogy collection. (from MinDat)12 May 2019, 4:50 pm - Timan-Pechora Basin

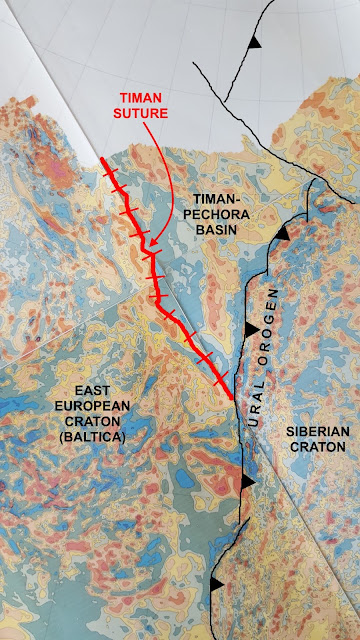

This is part of the magnetic map of the former Soviet Union. It reveals three continental blocks and their amalgamation to form part of Eurasia. The Siberian Craton (a craton is a strong, usually fairly old block of continental crust) collided with and became attached to the East European Craton beginning about 300 million years ago, about the same time as Europe and Africa began to collide with North America to form the Appalachians. Here, the collision produced the Ural Mountains (orogeny means mountain building). The Ural-building collision went on for close to 100 million years. Much longer ago, at least 520 million years ago and maybe as long ago as 650 million years, a relatively small continental block, labeled “Timan-Pechora Basin” in the image, was amalgamated to the East European Craton. The Timan Suture marks the position of that collision. Today that’s just a range of low hills, but it would have been high mountains at the time of the collision. The Timan-Pechora block was fully part of the East European Craton when Siberia collided with both of them. For a sense of scale, the distance along the coastline (edge of data) from the Timan Suture to the thin black line is about 400 miles.

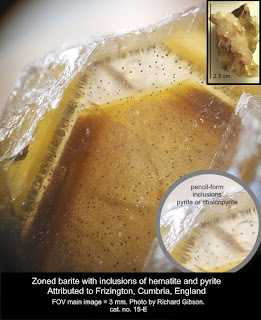

This is a very broad-brush look at these magnetic data (I spent the year 1990 making detailed interpretations of the maps for oil exploration).11 May 2019, 3:25 pm - Barite with inclusionsBeginning with this post, the blog is "blog only" - no more podcasts, at least not for now.

The brownest zones of barite in this example result from dense inclusions of deep reddish material, probably hematite, in blebs smaller than a hundredth of a millimeter barely visible in the image. The larger inclusions you can see here are brassy spheres, triangular prisms, and elongate pencils, and are probably pyrite but chalcopyrite is possible. The lower right inset shows the pencil forms a little better than the main image.

The upper right inset is the entire 2.3-cm specimen. I don’t have a locality, but I attribute it to Frizington, Cumbria, England, because of the barite forms and inclusions, the associated white calcite (colored pink in places by hematite), and the presence of a few tiny hematite blades on the surface.

Zoning in crystals results from changes in the environment while the crystal is growing. In this case there were variations in the iron (and maybe copper, if some of the inclusions are chalcopyrite) content in what was otherwise a solution dominated by barium and sulfur (barite is barium sulfate).

Zoned crystals are common, although this one is kind of dramatic and I think the pencil-like inclusions, standing in ranks perpendicular to the crystal faces, are unusually weird and cool. It would be more difficult for such things to form than for a barite crystal surface to be coated with something and then have more barite deposited over that coating.

The brownest zones of barite in this example result from dense inclusions of deep reddish material, probably hematite, in blebs smaller than a hundredth of a millimeter barely visible in the image. The larger inclusions you can see here are brassy spheres, triangular prisms, and elongate pencils, and are probably pyrite but chalcopyrite is possible. The lower right inset shows the pencil forms a little better than the main image.

The upper right inset is the entire 2.3-cm specimen. I don’t have a locality, but I attribute it to Frizington, Cumbria, England, because of the barite forms and inclusions, the associated white calcite (colored pink in places by hematite), and the presence of a few tiny hematite blades on the surface.

Zoning in crystals results from changes in the environment while the crystal is growing. In this case there were variations in the iron (and maybe copper, if some of the inclusions are chalcopyrite) content in what was otherwise a solution dominated by barium and sulfur (barite is barium sulfate).

Zoned crystals are common, although this one is kind of dramatic and I think the pencil-like inclusions, standing in ranks perpendicular to the crystal faces, are unusually weird and cool. It would be more difficult for such things to form than for a barite crystal surface to be coated with something and then have more barite deposited over that coating.

—Richard I. Gibson10 May 2019, 6:11 pm - More Episodes? Get the App