REBEL Cast

Salim R. Rezaie, MD

Rational Evidence Based Evaluation of Literature

- 6 minutes 54 secondsREBEL Core Cast 131.0 – Traumatic Arthrotomy

- Always suspect an open joint if there is a laceration, regardless of size, the lies over joint

- CT scan of the affected joint is widely considered to be the standard approach to evaluation but the saline load test may be useful in certain circumstances.

- Obtain emergency orthopedics consultation for all open joints and administer antibiotics and update tetanus in all patients

REBEL Core Cast 131.0 – Traumatic Arthrotomy

Click here for Direct Download of the Podcast.

Definition: a deep laceration that extends into the joint capsule, exposing the intra-articular surface to the environment

- A laceration into the joint exposes the normally sterile intra-articular contents to external contamination

- Inoculation of the joint often results in septic arthritis

Physical Exam:

- Laceration over joint (can be variable in size)

- Local wound exploration may be sufficient in identifying the open joint

- Exam findings suspicious for joint capsule involvement:

-

- Air bubbles

- Extravasation of joint fluid – straw colored, viscous, sometimes oily in appearance

-

Diagnostic testing:

- Imaging:

- X-ray

- Limited ability to see air in joints but a reasonable first test

- CT scan

- Intra-articular air visualized on CT (Konda 2013)

- May be up to 100% sensitive for joint violation

- Study limited by small numbers, inclusion bias + inadequate gold standard

- May be considered the standard evaluation modality in many settings.

- Intra-articular air visualized on CT (Konda 2013)

- X-ray

- Saline load test

- Has mainly been supplanted by CT scan due to ease in obtaining, reported performance characteristics, consultant recommendation and difficulty in interpreting test.

- Useful if physical examination equivocal or plain radiographs non-diagnostic

- Technique (Video)

- Perform arthrocentesis of the joint with a large bore needle (18-20 gauge)

- Sterile saline is injected into the joint while passive movement is applied to the joint

- The laceration site is watched for saline extravasation indicating communication between the joint and external environment

-

- Sensitivity ranges from 34%-99% depending on the study, joint, and the amount of saline used to load the joint (Browning 2016)

- Methylene blue

- Aids in distinguishing a true positive from additional bleeding from the wound

- Recent studies suggest that the addition of methylene blue does not increase sensitivity if a sufficient amount of saline is used (Metzger 2012)

- Volume of fluid injected

- Varies depending on the joint in which you are injecting

- Higher volumes increase sensitivity but also increase pain for the patient

- Knee Joint (Keese 2007)

- 50 ml: Sensitivity of about 46%

- 194 ml: sensitivity of 95%

- Elbow Joint (Feathers 2011)

- 20 ml: Sensitivity of 86%

- 40 ml: Sensitivity of 95%

- Ankle Joint (Bariteau 2013)

- 7 ml: Sensitivity of 50%

- 30 ml: Sensitivity of 95%

ED Management:

- Reduce open fractures if present

- Irrigate grossly contaminated wounds in the ED

- Immobilize the joint to prevent further injury

- Obtain early orthopedic evaluation for joint exploration, and washout to be performed within 6-24 hours

- Tetanus prophylaxis

- Prophylactic antibiotics (best if given within 6 hours)

- Staph/strep coverage: 1st generation cephalosporin (i.e. cefazolin or cefuroxime)

- If risk factors for MRSA present, use agent with activity against MRSA (i.e. vancomycin)

- If significant soft tissue injury, add gram negative coverage like late generation cephalosporin, extended-spectrum penicillin, or aminoglycoside (i.e. gentamycin)

- If concern for fecal or clostridial infection, add high dose penicillin (i.e. zosyn)

- If seawater contamination and concern for vibrio vulnificus, add doxycycline

Post Peer Reviewed By: Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter/X: @srrezaie)

The post REBEL Core Cast 131.0 – Traumatic Arthrotomy appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.

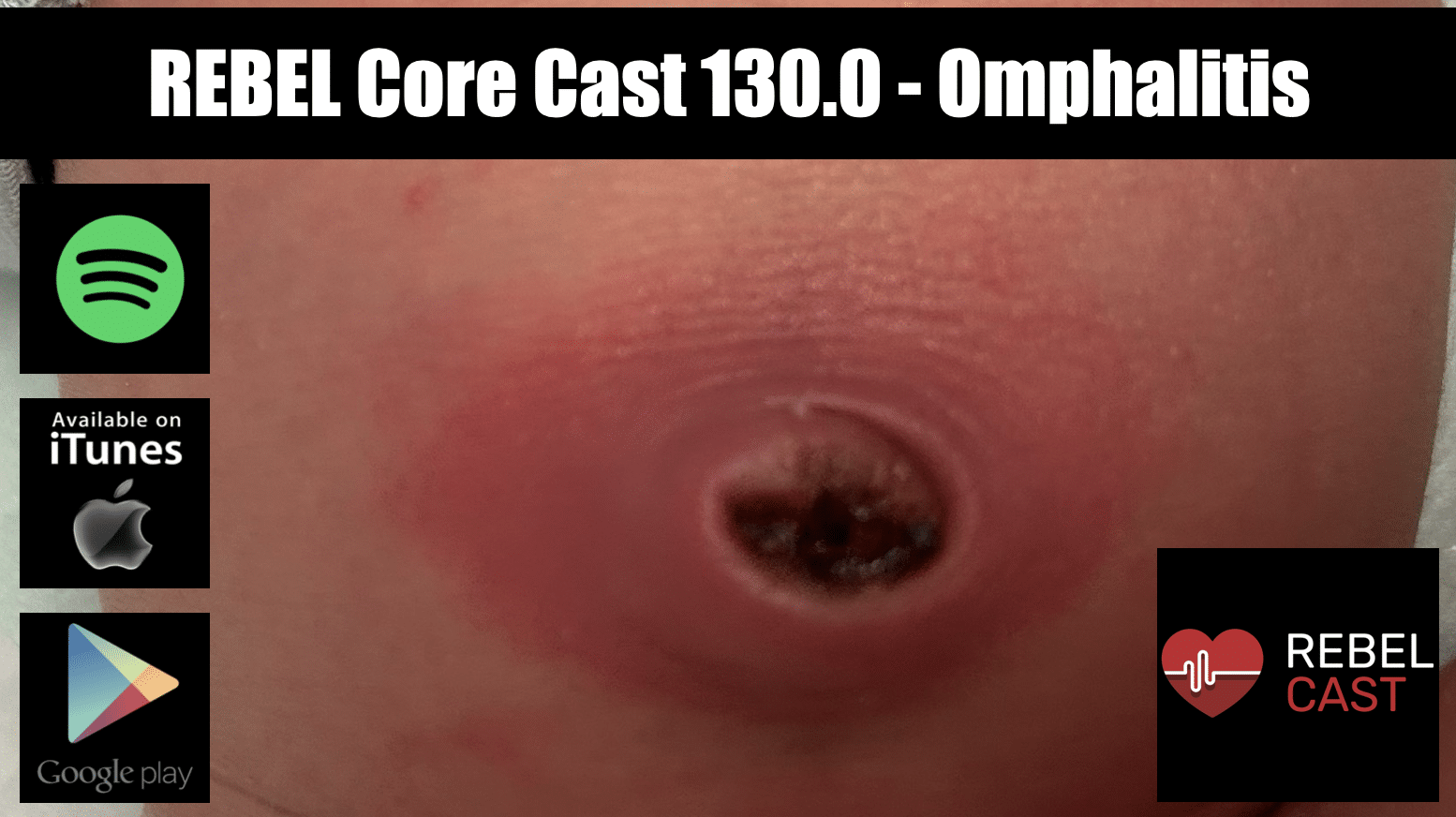

13 November 2024, 4:00 pm - 5 minutes 45 secondsREBEL Core Cast 130.0 – Omphalitis

Take Home Points

Take Home Points- Early diagnosis: erythema and warmth of the skin surrounding the umbilicus isn’t normal. Get labs, start abx and get the patient admitted

- Consult peds surgery on all of these patients as progression to nec fast, while uncommon, is devastating

- If the patient appears toxic or has systemic symptoms, the simply omphalitis has progressed and aggressive treatment including surgery is likely indicated

REBEL Core Cast 130.0 – Omphalitis

Click here for Direct Download of the Podcast.

Post Peer Reviewed By: Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter/X: @srrezaie)

The post REBEL Core Cast 130.0 – Omphalitis appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.

30 October 2024, 3:30 pm - 6 minutes 13 secondsREBEL Core Cast 129.0 – Gastric Lavage

Take Home Points

Take Home Points- Orogastric lavage may still play an important role in treatment of the overdose patient. Do not perform lavage if the ingestion has limited toxicity at any dose or the ingested dose is unlikely to cause significant toxicity.

- Strongly consider orogastric lavage in a patient who has taken an overdose of drugs that are particularly toxic, suspected extreme doses associated with high morbidity/mortality and do not have easily available and effective antidotes.

- Secure the airway prior to placing the lavage tube to minimize aspiration risk.

REBEL Core Cast 129.0 – Gastric Lavage

Click here for Direct Download of the Podcast.

Post Peer Reviewed By: Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter/X: @srrezaie)

The post REBEL Core Cast 129.0 – Gastric Lavage appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.

16 October 2024, 3:00 pm - 16 minutes 50 secondsREBEL Core Cast 128.0 – Toxic Alcohols

Take Home Points

Toxic alcohols generally refer to methanol and ethylene glycol as these substances pose significant metabolic derangement and end-organ damage.

Toxic alcohols generally refer to methanol and ethylene glycol as these substances pose significant metabolic derangement and end-organ damage.- Patient who present shortly after ingestion will simply look inebriated – no different than ethanol intoxication. At this point, patients will have an elevated osmolar gap and little to no anion gap.

- Patient who presents in a delayed fashion after ingestion may have a normal osmolar gap however will manifest the signs of end-organ damage: anion gap metabolic acidosis, visual impairment, or renal dysfunction.

- The osmolar gap is poorly sensitive, specific surrogate measure that is used to detect the presence of toxic alcohols. A normal osm gap does not rule out a toxic alcohol ingestion.

- Management includes fomepizole, hemodialysis, and vitamin supplementation.

REBEL Core Cast 128.0 – Toxic Alcohols

Click here for Direct Download of the Podcast.

Reference: Wiener SW. Chapter 106. Toxic Alcohols. In: Nelson LS, Howland MA, Lewin NA, Smith SW, Goldfrank LR, Hoffman RS, , Flomenbaum NE. eds. Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies, 11e New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019. Accessed October 2, 2024.

Guest Expert: Dr. Sanjay Mohan, MD (Link)

Post Peer Reviewed By: Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter/X: @srrezaie)

The post REBEL Core Cast 128.0 – Toxic Alcohols appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.

2 October 2024, 3:00 pm - 9 minutes 6 secondsREBEL Core Cast 127.0 – Penetrating Neck Injuries

- Anticipate anatomically challenging airways and consider early intubation prior to loss of airway anatomy.

- Skip the zones of the neck and focus on hard signs of vascular (Shock w/o another source, Pulsatile bleeding, Expanding hematoma, Audible bruit, Signs of stroke) or aerodigestive (Airway compromise, Bubbling wound, Extensive SubQ air, Stridor, Significant hemoptysis/hematemesis). The presence of hard signs indicates the need to go to the OR or for angiographic intervention.

- Control hemorrhage with a single finger and direct pressure.

REBEL Core Cast 127.0 – Penetrating Neck Injuries

Click here for Direct Download of the Podcast.

Post Peer Reviewed By: Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter/X: @srrezaie)

The post REBEL Core Cast 127.0 – Penetrating Neck Injuries appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.

18 September 2024, 3:30 pm - 24 minutes 51 secondsREBEL Core Cast 126.0 – Peds Hem Onc Emergencies

Take Home Points

Take Home Points- Early administration of antibiotics (within 60 min) in patients with fever and neutropenia is life saving.

- Fever in sickle cell is an emergency and always requires cultures and antibiotics even if the child appears well.

- Avoid sedation and lying supine and steroids in patients with mediastinal masses.

- Red flags in patients with headaches that may suggest a brain tumor include signs of increased intracranial pressure, focal neurological signs, seizures or ataxia.

REBEL Core Cast 126.0 – Peds Hem Onc Emergencies

Click here for Direct Download of the Podcast.

Post Peer Reviewed By: Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter/X: @srrezaie)

The post REBEL Core Cast 126.0 – Peds Hem Onc Emergencies appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.

10 July 2024, 3:30 pm - 7 minutes 56 secondsREBEL Core Cast 125.0 – Hyperkalemia

Take Home Points

Take Home Points- Always obtain an EKG in patients with ESRD upon presentation

- Always obtain an EKG in patients with hyperkalemia as pseudohyperkalemia is the number one cause

- If the patient with hyperkalemia is unstable or has significant EKG changes (wide QRS, sine wave) rapidly administer calcium salts

- In patients who are anuric, early mobilization of dialysis resources is critical

REBEL Core Cast 125.0 – Hyperkalemia

Click here for Direct Download of the Podcast.

Definition: A serum potassium level > 5.5 mmol/L

Epidemiology

- Common electrolyte disorder

- 10% of hospitalized patients (Elliott 2010)

Causes

- Pseudohyperkalemia: extravascular hemolysis

- Renal failure (potassium is primarily eliminated by the kidneys)

- Acidosis

- Massive cell death (tumor lysis syndrome, rhabdomyolysis, burns, crush injuries, hemolysis)

- Drugs: ACEI, ARBs, Spironalactone, NSAIDs, Succinycholine

Clinical Manifestations

- Mild hyperkalemia often asymptomatic

- Cardiac Effects

- Increased potassium raises the resting membrane potential of cardiac myocytes

- Slows ventricular conduction

- Decreases length of action potential

- Increases cardiac myocyte excitability

- Cardiac effects can manifest in lethal dysrhythmias

- Neuromuscular Effects

- Paresthesias

- Weakness

- Flaccid paralysis

- Depressed or absent deep tendon reflexes

Diagnosis

- Suspect hyperkalemia in ALL patients with renal impairment, especially end-stage renal disease (ESRD)

- Serum potassium

- Can be artificially elevated by extravascular hemolysis

- Blood gas results may differ from standard metabolic panels by up to 0.5mmol/L

- 12-Lead EKG

- Screening test that can rapidly detect severe cardiac manifestations of hyperkalemia

- A normal EKG with a significant serum potassium elevation should raise concerns for spurious results (extravascular hemolysis)

- Sensitivity of EKG to detect hyperkalemia is poor (Wrenn 1991, Aslam 2002, Montague 2008)

- Classic EKG findings

- PR prolongation

- Peaked T waves

- Loss of P waves

- Widening of QRS complex

- Sine wave

- Ventricular Fibrillation

- Asystole

- Note: Hyperkalemia can present with a number of “non-classic” EKG findings including AV blocks and sinus bradycardia (Mattu 2000)

- Note: Hyperkalemic EKG changes do not necessarily occur in order (i.e. patients can jump from peaked T waves to sine wave)

Management

Basics: ABCs, IV, O2, Cardiac Monitor and, 12-lead EKG

- Identify + treat underlying cause of hyperkalemia (i.e. rhabdomyolysis -> hydration)

- Remove inciting factors (i.e. stop ACEI, NSAIDs etc)

Asymptomatic Patients without EKG Changes

- Eliminate potassium from the body

- Binding agents (SPS, Sodium zirconium cyclosilicate etc)

- Enhance renal elimination

- Intravenous hydration if volume depleted

- Consider potassium wasting loop diuretics (i.e. furosemide)

- Dialysis for anuric patients (i.e. ESRD)

Symptomatic Patients or Significant EKG Changes

- Stabilize cardiac myocytes with calcium salts

- Mechanism: Recreates the electrical gradient leading to rapid reversal of cardiac effects and rapid stabilization

- Two Options: CaGluconate, CaCl2

- No difference in time to onset (1st pass metabolism is a myth)

- Dose: 1 ampule CaCl2 (270 mg Ca2+) = 3 ampules CaGluconate (90 mg Ca2+/ampule)

- Onset of action: seconds to minutes

- Duration: 20-30 minutes

- Shift potassium into intracellular space (temporary)

- Insulin (Moussavi 2021)

- Mechanism: Activation of the Na-K-ATPase

- Dose: 5-10 units IV

- Onset of Action: < 15 min

- Effect: Lowers potassium by about 0.6 mmol

- Duration of action: 30-60 min

- Give with dextrose (0.5 – 1 g/kg) unless hyperglycemia present

- Caution: Duration of action of insulin may outlast administered dextrose. Be vigilant for hypoglycemia

- Beta-adrenoreceptor agonists (i.e. albuterol)

- Mechanism: Activation of beta receptors

- Dose: 10-20 mg inhaled (4-8 standard ampules)

- Onset of Action: < 15 min

- Effect: Lowers potassium by about 0.6 mmol

- Duration of action: 30-60 min

- Additive effect with insulin (Allon 1990)

- Note: Unlikely to have effect in patients taking beta-adrenoreceptor blocker medications

- Sodium Bicarbonate (NaHCO3)

- Evidence for the efficacy of NaHCO3 to lower serum potassium is scant and contradictory (Elliott 2010, Weisberg 2008)

- Insulin (Moussavi 2021)

- Eliminate potassium from the body (see above)

Asymptomatic Patients with Minor EKG Changes

- Minimal recommendations on managing this clinical entity

- Eliminate potassium from the body (see above)

- Consider calcium salt administration: patients can rapidly progress through EKG changes and calcium administration may prevent this from occurring. However, the effects of calcium are temporary and offer no long-term protection

- Consider medications to shift potassium intracellularly while waiting for elimination

Take Home Points

- Always obtain an EKG in patients with ESRD upon presentation

- Always obtain an EKG in patients with hyperkalemia as pseudohyperkalemia is the number one cause

- If the patient with hyperkalemia is unstable or has significant EKG changes (wide QRS, sine wave) rapidly administer calcium salts

- In patients who are anuric, early mobilization of dialysis resources is critical

References

Elliott MJ et al. Management of patients with acute hyperkalemia. CMAJ 2010; 182(15): 1631-5. PMID: 20855477

Wrenn K et al. The ability of physicians to predict hyperkalemia from the ECG. Ann Emerg Med 1991; 20(11): 1229-32. PMID: 1952310

Aslam S et al. Electrocardiography is unreliable in detecting potentially lethal hyperkalaemia in hemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002; 17: 1639-42. PMID: 12198216

Montague BT et al. Retrospective review of the frequency of ECG changes in hyperkalemia. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008; 3:324–330. PMID: 18235147

Mattu A et al. Electrocardiographic manifestations of hyperkalemia. Am J Emerg Med 2000; 18: 721-9. PMID: 11043630

Allon M, Copkney C. Albuterol and insulin for treatment of hyperkalemia in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 1990; 38:869–872. PMID: 2266671

Weisberg LS. Management of hyperkalemia. Crit Care Med 2008; 36: 3246-51. PMID: 18936701

Moussavi K et al. Reduced alternative insulin dosing in hyperkalemia: a meta-analysis of effects on hypoglycemia and potassium reduction. Pharmacotherapy 2021; 41(7): 598-607. PMID: 33993515

Post Peer Reviewed By: Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter/X: @srrezaie)

The post REBEL Core Cast 125.0 – Hyperkalemia appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.

26 June 2024, 3:00 pm - 14 minutes 41 secondsREBEL Core Cast 124.0 – Hyperinsulinemia Euglycemia Therapy

Take Home Points

Take Home Points- Management of severe beta-blocker and calcium-channel blocker toxicity should occur in a stepwise fashion: potential gastric decontamination, multiple lines of access, judicious fluids, calcium, glucagon, and vasopressors as needed.

- Initiation of high dose insulin therapy requires a tremendous amount of logistical and cognitive resources as it requires cross-disciplinary collaboration and is prone to mismanagement.

- If the patient doesn’t respond to maximum pharmacologic therapy, venous-arterial ECMO should be considered.

REBEL Core Cast 124.0 – Hyperinsulinemia Euglycemia Therapy

Click here for Direct Download of the Podcast.

Background and Physiology

- Shock secondary to beta-blocker (BB) or calcium-channel blocker (CCB) toxicity bears a tremendous degree of morbidity and mortality.

- According to the 2022 Annual Report of the National Poison Data System from America’s Poison Center, CCBs and BBs account for the sixth and seventh largest number of fatalities from overdose.1

- Recall that cardiac output is a function of both stroke volume and heart rate. The natural response to diminishing stroke volume is a compensatory rise in heart rate (tachycardia). Keep a low threshold to search a patient’s medication list for BB/CCBs, when a hypotension is seen with a “normal heart rate.”

Clinical Manifestations

- Both BBs and CCBs ultimately cause reduced levels of intracellular calcium within myocytes. Depending on the degree of toxicity, subsequent effects include: decreased systemic vascular resistance, vasodilation, bradycardia, various conduction delays, and ultimately hypotension and cardiogenic shock.

- In addition to abnormal vital signs, look for surrogates of poor clinical perfusion: acidemia, lactate, decreasing urinary output

Traditional Management

- Consider GI decontamination to reduce systemic absorption: 1g/kg up to 50g of activated charcoal. Patient must be alert or the airway must be secured as to avoid aspiration.

- Obtain multiple lines of intravenous access (3 PIVs or triple lumen CVC) and provide a judicious amount of fluids. (more on this below)

- Pharmacotherapy

- Calcium Gluconate: 1-3g intravenous

- Glucagon: 3mg-5mg slow intravenous push. Rapid administration may induce nausea and emesis.

- Vasopressors as a bridge to…

HIET

- Mechanism of action is still not fully elucidated however several factors are implicated:

- Insulin augments cardiac contractility by activating “reverse-mode” Na-Ca exchange and subsequently increasing calcium concentration in the sarcoplasmic reticulum. 2

- At a resting physiologic state, the heart utilize free fatty acids as its primary energy course. Under stressed conditions, glucose is used instead. Insulin helps to facilitate glucose metabolism.

- HIET Dosing: 1 unit/kg IV bolus. Then infusion starting at 1 unit/kg/hr infusion and titrate q30-60 minutes, keeping in mind that effects are not instant. Relative maximum is ~10 unit/kg/hr.

- If glucose <250 mg/dL, administer a bolus of dextrose 25-50 g (or 0.5-1 g/kg) IV.

- Ask pharmacy to concentrate insulin from 1 unit/mL to 10 units/ml.

- Patients often succumb to volume overload given pre-existing cardiac disease and the volume of medical resuscitation through their hospital stay.

- Once HIET is initiated, dextrose and potassium infusions should simultaneously be started to obviate hypoglycemia and hypokalemia

- Dextrose: 0.5-1 g/kg/hr via D50/D20

- Replete potassium to a minimum of 3.5mEq/L

- A central venous catheter (often a triple lumen) is often needed to emergently replete potassium and provide D50/D20 safely (given its high osmolarity)

- Serial monitoring of dextrose (q15-30 minutes) and potassium (q1 hour) is critical

- HIET has been demonstrated to improve perfusion without necessarily increasing SVR/MAP – while MAPs may not markedly increase dramatically in the short term, obtain serial blood gases, lactate, and track urinary output to track perfusion. 3

Hyperinsulinemia Euglycemia Therapy (HIET) for BB/CCB Toxicity

- Management of severe beta-blocker and calcium-channel blocker toxicity should occur in a stepwise fashion: potential gastric decontamination, multiple lines of access, judicious fluids, calcium, glucagon, and vasopressors as needed.

- Initiation of high dose insulin therapy requires a tremendous amount of logistical and cognitive resources as it requires cross-disciplinary collaboration and is prone to mismanagement.

- HIET Dosing: 1 unit/kg IV bolus. Then infusion starting at 1 unit/kg/hr infusion and titrate q30-60 minutes, keeping in mind that effects are not instant. Relative maximum is ~10 unit/kg/hr.

- HIET therapy requires simultaneous dextrose and potassium infusions as insulin will induce hypoglycemia and shift potassium intracellularly.

- If the patient doesn’t respond to maximum pharmacologic therapy, venous-arterial ECMO should be considered.

References

- Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Beuhler MC, et al. 2022 Annual Report of the National Poison Data System® (NPDS) from America’s Poison Centers®: 40th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2023;61(10):717-939. doi:10.1080/15563650.2023.226898

- von Lewinski D, Bruns S, Walther S, Kögler H, Pieske B. Insulin causes [Ca2+]i-dependent and [Ca2+]i-independent positive inotropic effects in failing human myocardium. Circulation. 2005;111(20):2588-2595. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.497461

- Holger JS, Engebretsen KM, Fritzlar SJ, Patten LC, Harris CR, Flottemesch TJ. Insulin versus vasopressin and epinephrine to treat beta-blocker toxicity. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2007;45(4):396-401. doi:10.1080/15563650701285412

Post Peer Reviewed By: Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter/X: @srrezaie)

The post REBEL Core Cast 124.0 – Hyperinsulinemia Euglycemia Therapy appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.

12 June 2024, 3:30 pm - 6 minutes 30 secondsREBEL Core Cast 123.0 – Posterior Epistaxis

Take Home Points:

Take Home Points:- Posterior epistaxis is a rare, life-threatning presentation.

- The key is in identifying and rapidly gaining control with a posterior pack or foley catheter.

- These patients often require surgical intervention so get ENT to the bedside and admit to a place with a higher level of monitoring.

REBEL Core Cast 123.0 – Posterior Epistaxis

Click here for Direct Download of the Podcast.

Recognition

- Typically will have heavy bleeding both anteriorly and posterior into the oropharynx. These patients have a tough time because they’re continually trying to spit out or swallow blood

- Tachycardia is common and hypotension while not common isn’t unexpected. Very different from anterior epistaxis where VS usually unremarkable or maybe a bit of hypertension

- Failure of anterior pressure or packing to stop bleeding: apply pressure but still see brisk posterior bleeding or even place b/l pack and see continued posterior bleeding

Start with the basics

- IV, Supp O2, Monitor

- Consider blood products if the patient appears to be losing a lot of blood or they report heavy blood loss. VS abnormalities can drive this as well

- Strongly consider reversal of AC (this will typically come after control)

Stopping the Bleeding

- PPE: these things bleed like stink. Anecdote. Gown, gloves and most importantly eye and face protection

- Ideal: commercial posterior pack

- Two balloons – one for anterior, one for posterior

- Place the device (straight back parallel to the floor)

- Inflate anterior balloon (10-15 cc) of air

- If still bleeding, inflate posterior balloon (5-10 cc of air)

- Foley: if no commercial device

- Place foley catheter just as you would place a nasal tampon

- When you see the tip of the foley in the posterior pharynx, inflate balloon (5-10 cc)

- Need to pull back a bit and secure (can do this with tape on the nose)

Post Placement Care

- Antibiotics: standard practice to give cephalexin or amox/clav. Literature doesn’t defend this approach but, the lit is pretty sparse. The idea behind abx is to prevent things like AOM and TSS but neither should be much of an issue with short term placement

- ICU Admission?

- Traditional teaching is that these patients are at risk for life-threatening bradydysrhythmias and should go to the ICU

- Literature here is non-existent. Two oft-cited articles

- Cassisi Laryngoscope 1971 – no mention of cardiac events in the article but widely cited

- Zeyyan Laryngoscope 2010 – slightly lower HR in the packing group but no bradydysrhythmias

- Before throwing ICU out

- Hypoxia can occur – Cassisi found about a 20 mm Hg drop in PaO2 but all the patients in this publication were sedated so the packing may not have been the issue

- look at Viducich 1995 Acad Emerg Med – showed that 18% of the 88 patients with posterior epistaxis required a surgical intervention. With that in mind, you want to consider placing patients into a setting where they can be frequently reassessed – perhaps SDU. This will be pretty location specific. If you treat a posterior bleed at a hospital without ENT, I would transfer as surgical intervention is pretty common

REBEL EM: Do Patients with Epistaxis Managed by Nasal Packing Require Prophylactic Antibiotics?

REBEL EM: Do Patients with Posterior Epistaxis Managed by Posterior Packs Require ICU Admission?

EMRAP HD: Epistaxis Posterior Pack

References

- Cassisi NJ et al. Changes in arterial oxygen tension and pulmonary mechanics with the use of posterior packing in epistaxis: a preliminary report. Laryngoscope 1971; 81(8): 1261-6. PMID: 5569677

- Zeyyan E et al. The effects on cardiac function and arterial blood gas of totally occluding nasal packs and nasal packs with airway. Laryngoscope 2010; 120: 2325-2330. PMID: 20938948

- Loftus BC et al. Epistaxis, medical history and the nasopulmonary reflex: what is clinically relevant. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1994; 110: 363-9. PMID: 8170679

- Viducich RA et al. Posterior epistaxis: clinical features and acute complications. Acad Emerg Med 1995; 25(5): 592-6. PMID: 7741333

- Corrales CE, Goode RL. Should patients with posterior nasal packing require ICU admission. Laryngoscope 2013; 123: 2928-9. PMID: 24114977

Post Peer Reviewed By: Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter/X: @srrezaie)

The post REBEL Core Cast 123.0 – Posterior Epistaxis appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.

29 May 2024, 3:30 pm - ANNEXA-1: Andexanet Alfa Associated with Harm in DOAC Reversal

Background: In May of 2018, Andexanet alfa gained accelerated approval by the FDA for the reversal direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) despite a lack of robust evidence for use. The 2022 AHA/ASA guidelines give the drug a level 2A recommendation and recommend it over the use of 4F-PCC (Greenberg 2022). FDA approval alongside guideline endorsement has led to the drug seeing a remarkable growth in use without a single high-quality study to support its use. The available data reports good hemostatic control: a subjective measure that is highly biased by unblinding and selection bias. More importantly, there are no studies comparing andexanet alfa to 4F-PCC or even placebo looking at important, patient-centered outcomes.

Background: In May of 2018, Andexanet alfa gained accelerated approval by the FDA for the reversal direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) despite a lack of robust evidence for use. The 2022 AHA/ASA guidelines give the drug a level 2A recommendation and recommend it over the use of 4F-PCC (Greenberg 2022). FDA approval alongside guideline endorsement has led to the drug seeing a remarkable growth in use without a single high-quality study to support its use. The available data reports good hemostatic control: a subjective measure that is highly biased by unblinding and selection bias. More importantly, there are no studies comparing andexanet alfa to 4F-PCC or even placebo looking at important, patient-centered outcomes.REBEL Cast WEE – ANNEXA-1 – Andexanet Alfa Associated with Harm in DOAC Reversal

Click here for Direct Download of the Podcast.

Article: Connolly SJ et al. Andexanet for Factor Xa Inhibitor-Associated Acute Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ANNEXA-1). NEJM 2024; 390(19): 1745-55. PMID: 38749032

Clinical Question: Does the use of andexanet alfa in patients on DOACs with intracerebral hemorrhage improved hemostatic efficacy?

Population: Patients > 18 years of age on a factor Xa inhibitor (taken within 15 hours of randomization) with an acute intracerebral hemorrhage.

Outcomes:

- Primary: Hemostatic efficacy assessed at 12 hours after randomization. Hemostatic efficacy was defined as:

- Excellent hemostatic efficacy: Change in hematoma volume < 20%

- Good hemostatic efficacy: Change in hematoma volume < 35%

- Increase in NIHSS < 7 points at 12 hours

- No receipt of rescue therapies within 3-12 hours from randomization

- No surgery to decompress the hematoma within 3-12 hours from randomization.

- Secondary: Percent change from baseline in anti-factor Xa activity during the first 2 hours from randomization

- Safety Endpoints (assessed at 30 days)

- Thrombotic events (ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, VTE).

- Death

Intervention: Andexanet alfa high-dose or low-dose bolus followed by infusion depending on time and dose from last DOAC use.

Control: Usual care

Design: Non-blinded, randomized controlled trial performed at 131 centers across 23 countries over 4 years.

Exclusions

- GCS < 7 at the time of consent

- NIHSS > 35

- Surgery planned within 12 hours of enrollment

- Thrombotic event within 2 weeks of enrollment

- Time from symptom onset > 6 hours

- Pregnancy

Results:

- Primary results

- 581 patients were assessed for eligibility across 131 sites over 4 years

- 31 excluded prior to randomization

- 20 excluded after randomization due to consent issues

- 530 analyzed for the safety outcomes

- 263 patients assigned to andexanet alfa arm

- 267 patients assigned to usual care arm

- 452 patients were analyzed for the primary outcome

- 85.5% (195/228) patients in the usual care arm received 4F-PCC

- 78.1% (175/224) patients in the andexanet arm received the low-dose regimen

- 581 patients were assessed for eligibility across 131 sites over 4 years

Critical Results

Andexanet alfa

Usual Care

Difference (95% CI)

P Value

Primary Outcome

Hemostatic Efficacy

67% (150/224)

53.1% (121/228)

13.4 (4.6 – 22.2)

0.003

NIHSS change < 7 points

87.9% (188/214)

83.0% (181/218)

4.6 (-2.0 – 11.2)

Secondary Outcome

Anti-Factor Xa % Change

-94.5% (-96.6 – 88.9)

-26.9% (-54.2 – -9.5)

Safety Outcome

Thrombotic Events

10.3%

5.6%

4.6 (0.1 – 9.2)

0.048

TIA

0

0

Ischemic Stroke

6.5%

1.5%

Myocardial Infarction

4.2%

1.5%

DVT

0.4%

0.7%

PE

0.4%

2.2%

Arterial Embolism

1.1%

0.7%

Death

27.8%

25.5%

0.51

Strengths:

- This is the first randomized trial comparing andexanet alfa to standard care in this patient group.

- Multicenter, multinational study increasing applicability of findings.

- Outcome assessors were blinded to treatment arm.

- Hematoma measurements were made with a standard protocol and central site adjudication.

- 12 hour NIHSS assessments were performed by health care professionals who were unaware of group assignments

Limitations:

- Study funded, designed, and supervised by AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals the maker of Andexanet alpha. Although, this does not refute the findings of this study, it should make readers skeptical.

- Clinicians were not blinded to the treatment arm patients were randomized to. This may introduce bias particularly in terms of subsequent treatments (treatments outside of reversal are not detailed in the study).

- Primary endpoint is not patient centered.

- Convenience sample of patients which introduces bias.

- There are some baseline differences between groups and it’s hard to say how this may have influenced the results.

- Exclusion criteria are likely to be difficult for clinicians to assess real time leading to protocol violation (particularly items like planned surgery and recent thrombotic event).

- Dose adjustment for time from ingestion likely to lead to protocol violation as this info difficult to assess.

- Exclusion criteria: Removed the sickest patients.

Discussion:

- The positive primary and secondary outcomes

- Both the primary (hematoma expansion) and secondary (anti-factor Xa reduction) outcomes were better in the andexanet group.

- Unfortunately, these are disease-oriented outcomes instead of patient centered outcomes: the patient doesn’t care if their hematoma expands by 20% or 25% or 30%. They care about clinically important outcomes like disability or death.

- The authors note that in other studies, hematoma expansion has been associated with worse outcomes, but this was clearly not demonstrated in this study as 90d mRS and death were the same between groups.

- Bottom line is that there wasn’t even a hint of improved clinical outcomes in the andexanet group.

- Safety outcomes favored the usual care group

- In general, larger studies or registries of patients are required to determine safety of a treatment.

- In this study, however, there is a clear signal for harm even with a small group of patients under ideal circumstances (ie enrolled within a study).

- Though death was not statistically different, the raw numbers favor usual care.

- Thrombotic events were clearly increased in the andexanet group.

- Across a larger group of patients outside of the pristine setting of a study, it is likely that we would see an increase in thrombotic events and death.

- Only 85.5% of patients in the usual care group received 4F-PCC

- Though there isn’t abundant evidence for the use of 4F-PCC in this setting, it does represent standard practice.

- The authors do not report about the subgroup of patients who did not receive 4F-PCC and their outcomes.

- If this data shows worse outcomes with no reversal treatment, it would suggest that usual care with 4F-PCC may be superior to andexanet alfa for clinical outcomes.

- If this data shows improved outcomes with no reversal treatment, it would suggest that specific reversal agents aren’t necessary.

- There were multiple protocol changes during the study. Typically, protocols should not be changed while the study is enrolling patients. This is often done to try to steer the data towards benefit.

- Initial power calculation was for 900 patients to achieve a 90% power to detect and absolute difference of 10% points in terms of hemostatic efficacy but then made an addendum to the protocol to stop after 450 patients.

- After this stop point, the safety and monitoring board recommended the trial be stopped.

- Though the authors state they had no knowledge of the effect prior, there is no clear explanation given for this change and it raises the possibility that the trial was stopped prior to additional data showing harm was collected.

- Drug cost

- Andexanet alfa costs between $30 – 50,000/treatment. This only takes into account drug costs (ie not monitoring, nursing costs etc).

- 4F-PCC costs around $5-6,000/treatment.

Author Conclusion: “Among patients with intracerebral hemorrhage who were receiving factor Xa inhibitors, andexanet resulted in better control of hematoma expansion than usual care but was associated with thrombotic events, including ischemic stroke.”

Clinical Take Home Point: The authors conclusions are correct. However, they don’t properly stress the findings.

Treatment of patients with intracerebral hemorrhage on a DOAC with Anexanet alfa did not improve clinical outcomes when compared to usual care. Based on safety data, andexanet alfa resulted in increased harm to patients. Andexanet alfa should not be part of the standard treatment in this scenario based on the available evidence.

References:

- Greenberg SM et al. 2022 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2022; 53(7). PMID: 35579034

- Connolly SJ et al. Andexanet for Factor Xa Inhibitor-Associated Acute Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ANNEXA-1). NEJM 2024; 390(19): 1745-55. PMID: 38749032

For More Thoughts on This Topic Checkout:

- REBEL EM: ANNEXA-4 – Andexanet Alfa and Factor Xa Inhibitors

- First10EM: Andexanet Alfa – More Garbage Science in the New England Journal of Medicine

- EM Lit of Note: Disutility, thy Name is ANEXXA-4

Post Peer Reviewed By: Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter/X: @srrezaie)

The post ANNEXA-1: Andexanet Alfa Associated with Harm in DOAC Reversal appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.

23 May 2024, 12:00 pm - Primary: Hemostatic efficacy assessed at 12 hours after randomization. Hemostatic efficacy was defined as:

- 8 minutes 6 secondsREBEL Core Cast 122.0 – Neutropenic Fever

Take Home Points: There are many causes of neutropenia, chemotherapy being by far the most dangerous. Febrile neutropenia is a condition conveying high mortality. Early administration of antibiotics is the only factor known to reduce this mortality. For a patient with neutropenic fever, remember that the body’s own flora is the greatest danger. Isolate, but ... Read more

Take Home Points: There are many causes of neutropenia, chemotherapy being by far the most dangerous. Febrile neutropenia is a condition conveying high mortality. Early administration of antibiotics is the only factor known to reduce this mortality. For a patient with neutropenic fever, remember that the body’s own flora is the greatest danger. Isolate, but ... Read moreThe post REBEL Core Cast 122.0 – Neutropenic Fever appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.

15 May 2024, 3:30 pm - More Episodes? Get the App

- https://rebelem.com/

- en-US

Your feedback is valuable to us. Should you encounter any bugs, glitches, lack of functionality or other problems, please email us on [email protected] or join Moon.FM Telegram Group where you can talk directly to the dev team who are happy to answer any queries.

EM Clerkship

EM Clerkship

Emergency Medical Minute

Emergency Medical Minute

The Internet Book of Critical Care Podcast

The Internet Book of Critical Care Podcast

Critical Care Scenarios

Critical Care Scenarios

EMCrit FOAM Feed

EMCrit FOAM Feed

Emergency Medicine Cases

Emergency Medicine Cases