This Rhetorical Life

This Rhetorical Life

A podcast dedicated to the practice, pedagogy, and public circulation of rhetoric in our lives.

- 36 minutes 42 secondsEpisode 33: Cruz Medina Interviews Ana Castillo

This summer, Cruz Medina reached out to This Rhetorical Life to share an interview he had done with Ana Castillo. As Medina states in this episode:

As a writer, Ana Castillo’s work is the art that identifies subject matter before those of us who are academics and scholars are able to apply lenses or qualify and quantify these rich sites of inquiry. And this is so important because there are still folks doing research on Latinas/os who bring in very little or no Latina/o scholarship, reaffirming what Jacqueline Jones Royster said in “When the First Voice You Hear Is Not Your Own,” that we are once again told that Columbus discovered America.

The intersections of Xicana feminism and Latinx literature addressing structured oppression are certainly not new, but in this contemporary political moment, it’s important to reaffirm a sense of survival. As Ana Castillo states:

We have to think about the people we have marginalized and disenfranchised most—and everybody in society at some point or another is. So it’s a fallacy to think that we have democracy and that everybody has the same opportunity. But, in terms of patriarchy, you know, women for eons have been kept in a secondary place. In terms of race issues in this country, which is only over 200 years old, but if we include the Americas, we’re talking about the conquest of Mexico and Peru and so on, so over half a millennium ago, here, of colonialism here. If we talk about other places in the world, it’s been going on for a very, very long time. Twenty or thirty years is just a drop in the bucket as far as some of the things that we’re addressing.

Read the transcript, or listen to the episode below. Featuring music from Blue Dot Sessions.

22 November 2016, 4:45 am - 38 minutes 52 secondsEpisode 32: Queer Public Cultures & the Rhetoricity of Sex Museums

“Homonormativity has had two kind of strains of theoretical emphasis, one of which has been the focus on neoliberal prerogatives and priorities into institutions and everyday life, and gay and lesbian formations in particular, and I say gay and lesbian for a reason. And the development of a prescriptive set of social codes that define what it means to be a cosmopolitan queer. And I think that, some people would say the movement has been hijacked, and I don’t disagree with those folks who make those arguments, but I don’t want to be so fatalistic about it. There is always time and space to rethink and remobilize along different lines and priorities.”

“And so I’m saying the word ‘sodomy’ I’m saying ‘queer,’ and this museum group, all heads turn at once away from their tour group, and they start listening to me and kind of following me around, right. And so this completely different history that was unexpected to them, to the person interviewing me, and to this random tour group, but they wanted to know, right? So there are all of these different histories that we can tell about these objects when we look through the lens of queer curatorship, when we look through the lens of all museums are sex museums.”

Today we’ll be talking about queer cultures, the rhetoricity of museum space, what role museums play in the formation of sexual subjectivities and national sexual cultures.

Click here to find full transcript of the episode.

Music from Otis McDonald: “Behind Closed Doors” and “Other Way”

https://thisrhetoricallife.syr.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Episode-32-This-Rhetorical-Life-Interview-with-Tyburczy.mp310 October 2016, 9:53 pm - 1 hour 8 minutesEpisode 31: An Interview with Ira Shor—Part Two

Original image found in: http://urbaned.commons.gc.cuny.edu/files/2014/02/ira-shor.jpeg

In any event, first [thing] we have to make contact with is the situation that we are entering and what kind of context we are teaching in, and for. And we have to then educate ourselves into the context.

In addition, the other thing is, the political conditions not only change from place to place; that is, some places are more open to allowing teachers to experiment, some places are very rigid and very punitive and repressive—so that we had to adjust to the political climate or the political profile around us. But that political climate was not only a function of place of where we were teaching, it is also a function of time.

Part two of the interview focuses on updates to critical pedagogy, including some of Shor’s more recent experiments in the classroom. We also talk a lot about movement work, about the pedagogies of movements, about the role that educators play and might play, and about what Shor has been doing inside and outside of formal academic institutions.

Once again, we let the tape run and give you a largely unedited interview. We have in mind an audience who is familiar with Shor and critical pedagogy but who may be interested in some of the personal details and specific points that Shor raises here that may not be available elsewhere.

And once again, a tiny chorus of Zebra finches make up the background noise for our conversation.

We hope you enjoy it.

https://thisrhetoricallife.syr.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/This-Rhetorical-Life-Episode-31-Ira-Shor-1.mp3For a full transcript of the episode, click on the following link: Episode 30 Transcript.

Music sampled in this episode is “Night Owl” from Broke For Free.

24 May 2016, 11:15 pm - 46 minutes 6 secondsEpisode 30: An Interview with Ira Shor

Image of Ira Shor from BBS Radio

In part one of our interview, Ira Shor tells us about growing up in the Bronx, his early experiences of education, joining social movements, practicing critical pedagogy, and his first encounters and early collaboration with the Brazilian educator Paulo Freire.

I discovered what it was like to sit next to a teenager from an affluent family, and how they dressed; and they had good complexions and I wondered how that happened, ’cause nobody I grew up with had a nice complexion; they all had nice teeth, I had terrible teeth, all my friends had terrible teeth; I wore my brother’s clothes, the hand-me-downs, they had their own clothes. So, it was like a very sudden contact with class differences because the schools I went to in the neighborhood, we were all from the same social class. It was an education for me but it also caused me a lot of—I don’t know—doubt, anxiety about who I was, and I began to feel insecure that I was ugly, badly dressed, that I smelled bad, that my hair was too oily, that my skin was too pimply, my teeth were too cracked, and so on. . .

So I had been moving in this direction of what I call critical literacy or critical pedagogy. And Paulo Freire, of course, was way ahead, he had been doing it—that was around 1970s, he’d been doing it for over twenty years. So then I began studying his work in earnest and used it as a foundation for writing my first book Critical Teaching and Everyday Life.

We hope you enjoy it, and check back next week for part two where we talk about social movements, political possibilities, and the current state of higher education.

To access a PDF of the full transcript of this episode, please click here: Episode 30 Transcript

The music sampled in this podcast is “Absurdius Rex” by Jovian Year.7 May 2016, 2:31 pm - 29 minutes 40 secondsEpisode 29: Reflections on Rhetoric and Citizenship

I just don’t understand why we have to talk about every mode of belonging as some kind

of citizenship. It just doesn’t make any sense to me. I’m interested in people’s practices of

resistance. I’m interested in people’s practices of belonging. […] I’m interested in people’s practices of world-making. — Karma ChavezI’m increasingly persuaded by those who argue citizenship is a toxic concept and a toxic term. When I do talk about folks who appeal to citizenship, I’m very aware of how often those appeals to citizenship are built on the constitutive exclusions of others, and that if we really want to mobilize a productive, an emancipatory sense of civic obligation and of civic duty, we’ve got to figure out a way to do it without buying into a privileging conception of citizenship. — Cate Palczewski

In Episode 29, we extend a conversation from the 2015 RSA Summer Institute Seminar on Rhetorics of Citizenship. Karrieann Soto and Kate Siegfried host the discussion with co-seminarians Karma Chavez and Cate Palczewski. The episode asks that we critically question rhetorics of citizenship in our scholarship and in daily life. For a full transcript, click here.

26 October 2015, 3:52 pm - 30 minutes 45 secondsEpisode 28: Transcription // Translation

We tend to assume that captioning is objective. It’s just copying down. We tend to privilege speech sounds, and there’s just something about speech that sort of makes it seem easier to transcribe. It’s straightforward and objective, but it’s so much more complex than that—especially when you add in non-speech sounds, especially when you consider that everybody has a different way of speaking. —Sean Zdenek

In our field even though composition and communication get hinged together, we have always talked about speech and writing as two different things, and they are and they will be, but I think captioning has this uncanny ability to merge those two back again to turn speech into writing and vice versa. —Brenda Brueggemann

I think at the core of what I’m thinking about is how our technologies and tools and then everything else like this room…which then you have to start thinking about architecture and especially modernist architecture, which was really meant to blockade the public and the private and noise and signal and everything like that. So that’s where maybe the work of Rickert and ambient rhetoric comes in, right? That there are all of these factors in terms of the way that we produce. It’s not, “I have an idea,” and I turn it into this thing. It’s all of these things from the file format to the bugs of the recorder we’re using to construction sounds in the background. I think it’s really just taking an approach and saying, there are all these other things that we’re playing with, not on. —Steven Hammer

Sometimes words are not adequate to describe music. And I think we all know that from listening to music—that music is extra-discursive at times. It’s felt in your body. It’s what Steph Ceraso calls “a multimodal event” where you’re feeling it physically and mentally feeling it. And it is logical and emotional and bodily. —Crystal VanKooten

For our 25th episode, we talked with other academic podcasters about the process and practice of podcasting and about sound production more generally. So for this episode, we were interested in thinking again about what it means to produce sound, to manipulate it through editing, to use it to craft logical and ethical and emotional arguments, to translate that meaning into words through transcribing, captioning, or asking students to critically reflect on their rhetorical aural choices. Episode 28 features interviews with Sean Zdenek, Brenda Brueggemann, Steven Hammer, and Crystal VanKooten that took place at this year’s CCCC in Tampa. In some clips, you may hear wind on the water, academic conversations echoing up from the lobby of the convention center, people clapping at the end of presentations. How do those ambient sounds complement or interfere with the content of the interviews? What are the implications of removing all the background sound from these clips, to make the audio as “polished” as possible? How do non-speech sounds contribute to how we make meaning?

To access a PDF of the full transcript of this episode, please click here: Episode 28 Transcript

The songs sampled in this episode are all Podington Bear: “Crunk in the Trunk,” “Alien Language,” “Human Transition,” and “Old Skin.”

23 April 2015, 6:04 pm - 13 minutes 51 secondsEpisode 27: Addressing Racism in the Classroom

I started the research really struggling to understand how seemingly good people could say such awful things, and that’s really what I wanted to understand. I think what I found is that people are not all one thing or another. They aren’t as awful as they seem in a particular moment. Our students are struggling I think to make sense of the world. –Jennifer Trainor

The Rock at Michigan State University painted #DONTSHOOT (September 2014)

As educators, we ought to discuss issues of racism and structural inequality in our classes. How do we do this with students who are in the process of forming their identities, beliefs, and values? Episode 27 features an interview with Jennifer Seibel Trainor, author of Rethinking Racism: Emotion, Persuasion, and Literacy Education in an All-White High School. In this episode, Trainor addresses anti-racist pedagogies and how we can talk about racism productively with students in the classroom, particularly when students may feel defensive about these issues. Trainor argues that we need to read deeper into the racist comments students make in the classroom to try to understand why they’re saying what they’re saying. You can read a review of Trainor’s book in Composition Forum here: http://compositionforum.com/issue/19/rethinking-racism-review.php

To access a PDF of the full transcript of this episode, please click here: Episode 27 Transcript.

The songs sampled in this episode are “Biomythos” by Revolution Void and “From Stardust to Sentience” by High Places.

20 February 2015, 3:44 pm - 53 minutes 46 secondsEpisode 26: Conversations about Academic Labor, Academic Freedom, and Palestine

There’s a certain set of conceits around academic freedom that limit its functionality and its practice, and those conceits often have to do with critiques of state power, critiques of colonization, critiques of structural violence. –Steven Salaita

I think using academic freedom as a way to open these more political conversations and more potentially more transformative conversations about Palestine and about labor, and allowing people to see the connections between these issues is really important. –Vincent Lloyd

Organizing around solidarity communities and connecting with allies and creating networks of solidarity in that way is so crucial. We cannot resist in isolation. –Carol Fadda-Conrey

Steven Salaita, Vincent Lloyd, and Carol Fadda-Conrey

How do the precarious conditions of academic labor affect the conversations that are possible in the academy? How does academic freedom protect—or fail to protect—academics from doing politicized work? How do questions of Palestine in particular affect our understandings of academic labor and academic freedom—and vice versa? In episode 26, Steven Salaita, who lost a tenured job offer after writing a series of tweets condemning Israel’s “Operation Protective Edge,” talks about the rhetorical commonplaces of civility in the academy, and the stakes of circulating critiques of state power on various media platforms. Assistant professor of religion Vincent Lloyd, and associate professor of English Carol Fadda-Conrey—who helped to organize a talk by Salaita on SU’s campus this fall—reflect on their academic trajectories and political work, offer suggestions for how young scholars can build networks of support, and remind us to realize the critical potential of our discipline.

To access a PDF of the full transcript, please click here: Transcript for Episode 26

The music sampled in this podcast is akaUNO’s “Hidden Leaves,” and “Another Word” by The Left Curve.

18 December 2014, 4:54 pm - 39 minutes 6 secondsEpisode 25: The Pod(cast) People Speak

Scholarship is designed to reach some sort of conclusion, even provisional, whereas the podcast because I think it’s still anchored in a kind of entertainment model [stardust clicking] is actually sort of less interested in conclusions and probably also—even if it was interested—that that’s sort of antithetical to the form that it’s working through. You want people to keep coming back. You want them to be able to take the episode with them.

—Nathaniel Rivers

Episode 25’s spectral pitch display in Adobe Audition

Welcome to our 25th episode! For this meta episode, we solicited contributions from other disciplinary podcasters, so we feature segments from Courtney Danforth and Harley Ferris who edit KairosCast, Casey Boyle and Nathaniel Rivers who co-produce PeoplePlaceThings, Eric Detweiler who helped launch Zeugma, Mary Hedengren who started Mere Rhetoric, and finally Kyle Stedman who hosts Plugs, Play, Pedagogy.

To access a PDF transcript of this episode, please click here: Episode 25 Transcript

The music we feature in this episode is “Synergistic Effect” by morgantj and “Scratch My Warhol (ft. Mr. Yesterday & Rey Izain)” by Scomber. There are references in the transcript for the many sound effects used.

14 November 2014, 7:19 pm - 50 minutes 34 secondsEpisode 24: On Ferguson

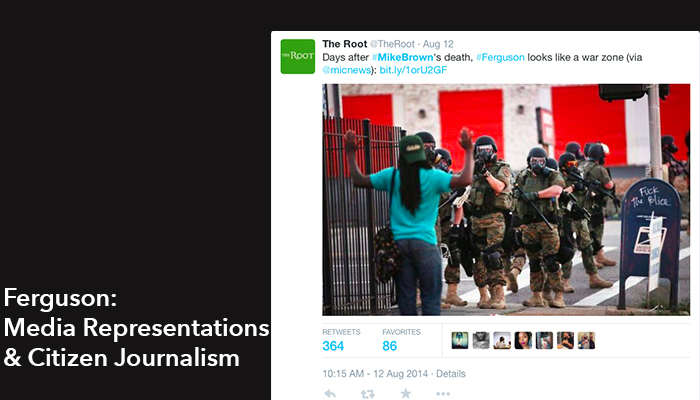

Can’t we find more creative ways to report these stories? The story of Michael Brown is so important, but we get trapped, I think, in this narrow narrative that we’ve been telling for a really long time. —Tessa Brown

Social media and mobile technology has particularly been important for people of color, for working class people, for immigrants, for LGBT people, people who belong to groups who have been traditionally marginalized in the media because they don’t have to not only wait for the media to tell their stories but they also don’t have to wait to have their stories be misconstrued, too, and have their stories misinterpreted. —Sherri Williams

These aren’t just flukes, these aren’t just accidents, these aren’t just deviations from an otherwise decent society. The whole society is bankrupt, its corrupt, its racist, its sexist, its homophobic, and ablist and because this is an entrenched deep issue it is going to have to be an entrenched long-term kind of movement to fight those kinds of things. —Nikeeta Slade

Tweet from The Root, Aug. 12: “Days after #MikeBrown’s death, #Ferguson looks like a war zone (via @micnews): bit.ly/1orU2GF

Episode 24 focuses on media representations of Ferguson, Missouri after the killing of Mike Brown. As Ben notes in the introduction, This Rhetorical Life focuses on the practice, pedagogy, and public circulation of rhetoric. By focusing on Ferguson, we connect all three: how rhetoric circulates around Ferguson, how our public texts work to either create and sustain or to challenge and resist unjust systems, and how we as writing instructors can help students analyze and flip unjust systems. This episode features interviews with three Syracuse graduate students: Tessa Brown, Sherri Williams, and Nikeeta Slade.

To access a PDF of the full transcript, please click here: Transcript for Episode 24

The music sampled in this podcast is “Strange Arithmetic” by The Coup, “Note Drop” by Broke For Free, “EMO Step Show” by The Custodian of Records, and “This is the End” By Springtide.

25 October 2014, 2:52 am - More Episodes? Get the App

Your feedback is valuable to us. Should you encounter any bugs, glitches, lack of functionality or other problems, please email us on [email protected] or join Moon.FM Telegram Group where you can talk directly to the dev team who are happy to answer any queries.

Prolific: A Podcast Journey Through Rhetoric, Composition, and Technical Communication

Prolific: A Podcast Journey Through Rhetoric, Composition, and Technical Communication

2018 CCCC Podcasts

2018 CCCC Podcasts

Zeugma

Zeugma

Mere Rhetoric

Mere Rhetoric

Plugs, Play, Pedagogy

Plugs, Play, Pedagogy

Rhetoricity

Rhetoricity