Baseball Happenings Podcast

Nick Diunte

Searching for a podcast that celebrates baseball's culture? Join Nick Diunte on the Baseball Happenings Podcast as we cover all of the bases with interviews from players, authors, and trendsetters. Join us on the web - www.baseballhappenings.net

- How Tom Qualters Went From Moneybags To Satchel Paige's Protegé

Tom Qualters, pictured here on his 1955 Topps card, passed away February 15, 2024.

Tom Qualters, pictured here on his 1955 Topps card, passed away February 15, 2024.

In 1953, the Philadelphia Phillies gave pitching phenom Tom Qualters a $40,000 contract, immediately making him their highest paid player, eclipsing the combined salaries of his Hall of Fame teammates Richie Ashburn and Robin Roberts. The fresh-faced right-hander quickly earned the nickname “Moneybags” and became the poster boy for the bonus rule, which required teams to keep a player on the active roster if his bonus exceeded $4,000.“It was somebody — a newspaper guy — who started that,” Qualters said about the nickname’s origin during a 2008 interview from his home.

Qualters died February 15, 2024 in Somerset, PA. He was 88. When we spoke in 2008, his memories were sharp, and he didn't hold back about his rushed entrance to the majors.

Bonus Baby Blues

Some teams struck gold with their “bonus baby” signings, producing Hall of Fame talents such as Sandy Koufax and Al Kaline. However, others turned a cold shoulder to players like Qualters. He pitched just one game on the mound during the two years the Phillies were required to keep him on the roster.

“That was about the worst rule they could have ever done,” he said. “You had to stay there two years. I was there 1953–54 and a little bit of 1955. … Basically, I was a batting practice pitcher. That was a sad thing. A lot of guys were in the same situation.”

The Phillies front office had different plans for Qualters. They shielded him from major league competition until he finished his mandated service time. For two years Qualters suffered on the bench while teammates resented him for holding a valued roster spot hostage.

“For some reason, the management in Philadelphia had this theory that if I went out there and got beat up, that it would ruin me,” he said. “What a bunch of bulls–t that was. It was the most frustrating period in my life. I hated being there. Some [players] were really good to me, and others ignored me altogether.

“I didn’t belong there. All I was doing was taking up space for someone who was a major league player. Imagine how that made me feel; I’m hurting the team, not helping them. I’m not even getting a chance to go out there and learn the game. It was two years out of my life that was totally a waste. You can sit there, talk and listen to guys — sure I got an education about the game, but it’s not like being on the field and playing it. You can’t learn to play the game by sitting on the bench. I could have bought a ticket. It was just a horrible thing.”

Supportive Teammates

Not all of the players, however, turned their backs on Qualters. He made it a point to acknowledge those who looked out for him.

“There were some guys who were very kind,” he said. “Robin Roberts and Curt Simmons were super guys. Jim Konstanty was [also] nice. There were other guys who didn’t want anything to do with me. As time wore on it got better and it wasn’t a personal thing anymore.”

Satchel Paige Intervenes

Qualters was relieved when the Phillies sent him to their Reidsville, North Carolina, Class B team. From there he was promoted to their Triple A team in Miami. With the Marlins, he linked up with Satchel Paige and thrived under the Hall of Famer’s tutelage.

After a shaky Triple A debut, Qualters showed up to the ballpark still doubting his abilities. The ageless Paige knew something was off about his new teammate.

“I’m sitting down in the bullpen, Satch sits down beside me and asked, ‘What’s wrong?’” Qualters recalled. “He recognized there was something wrong with me by the way I was acting. I did not know what to do so I just flat out told him that I did not have the courage to play the game and that I shook all over, etc. He called me Climber. He said, ‘Imma tell ya, Climber, them sons of bit–es can beat ya, but they can’t eat ya!’”.

Paige’s words were just the right recipe to help Qualters get through tough times on the mound. It was the push he needed to move forward with his career.

“Another tight game and I get called up there and I just get the shakes again,” he recalled. “I said to myself, ‘You sons of bit–es, you can beat me but you can’t eat me!’ It was all over from then on; I couldn’t wait to get out there.”

Baseball Card Legacy

Qualters eventually made it back to the Phillies briefly in 1957 before resurfacing with the Chicago White Sox in 1958. His time in Chicago led a 1959 Topps card appearance. Even though he pitched only 43 innings, he said that didn’t make a difference to the baseball card manufacturer.

“They didn’t care what you did or didn’t do, as long as you were on the team [you had a card],” he said.

Fifty years later, the amount of fan mail he received after being on the team for only one season still amazed him. Topps even had him sign 300 cards for their 2008 Topps Heritage set.

“It’s been crazy the last 4–5 years,” he said. “I probably get 3–4 of them per week. I have a card from 1959 when they went to the World Series. I didn’t even play [for the White Sox] in 1959, that’s when I hurt my arm. A guy came here with 300 cards I had to autograph and [Topps] paid me money for it.”

*I originally wrote this article for the Wax Pack Gods website.*

1 January 2025, 12:45 am - How Charlie Maxwell Quitting In Boston Fueled A Tigers All-Star Career

Charlie Maxwell's journey to becoming a celebrated Major League Baseball player was marked by perseverance through adversity. The Detroit Tigers fan favorite made it to All-Star status after almost giving up on the game early in his career. Maxwell, a Paw Paw, Michigan legend, died December 27, 2024. He was 97.The Boston Red Sox initially signed Maxwell in 1947 after serving in World War II, and he excelled in the minors, particularly with the Louisville Colonels in Triple-A. However, his tenure with Boston proved frustrating. Despite hitting close to .400 in Louisville and breaking home run records, Maxwell rarely saw playing time in the majors. Repeated call-ups and demotions left him disheartened, and he nearly quit baseball due to the lack of opportunities.

Reflecting on his time with Boston, Maxwell said in a 2008 phone interview, "They'd call me to Boston, they wouldn't play me for a few weeks, and send me back down. I didn't like that too well. I was doing so good at Louisville, hitting almost .400 a few times, but I never got to play in Boston."

His frustration peaked when management repeatedly misled him about playing time.

"They said I was going to play and never did. Nobody ever told me why," he said.

One incident encapsulated his discontent.

"I got to Chicago, I was there for three weeks and never got into a game—not even to pinch-hit. Then they sent me back to Louisville. I said, 'I'm not going to go.' I went back home and stayed for a week before they found me."

Breakthrough in Detroit

Maxwell’s career took a turn for the better when he joined the Detroit Tigers. Unlike in Boston, he finally got the chance to play regularly.

"In Detroit, Jim Delsing was struggling, and they never could get me out. I got the chance to play regularly, which I didn’t get in Boston," Maxwell said.

This shift allowed him to showcase his talent and establish himself as a reliable hitter. One of his defining moments came in a doubleheader, where he hit four home runs in a single day. Maxwell credited his success in Detroit to the opportunities he received and the chance to finally play without being overlooked.

"I was leading the team in homers, but I couldn’t even play,” he said. “The coaches made up the lineup, and that was the day I hit the four home runs. We won 12-15 in a row after that before getting beat."

Memorable Moments

Maxwell’s early years in the majors included unforgettable highlights. In 1951, his first three major league home runs were hit off Hall of Famers Satchel Paige, Bob Feller, and Bob Lemon. He recounted his grand slam against Paige with pride.

"I faced him the day before, and he struck me out on a hesitation pitch," he said. "The next day, I said, 'Well, I’ll be ready for that one,' and that’s when I hit the grand slam off him in St. Louis."

Reflections on the Game and Management

Maxwell spoke candidly about the challenges players faced during his era. He criticized the way minor league stars were often overlooked for major league roles and how poor management decisions could derail careers.

"There were guys playing regularly in the majors that didn’t compare to the guys in the minors trying to come up. A lot of players quit because of this," he said.

He had little respect for managers like Bill Norman, who Maxwell felt mismanaged the Tigers.

"Norman was one of the worst managers," Maxwell said. "It was chaos from day one. He was playing guys that shouldn’t be playing."

Similarly, he expressed frustration with Al Lopez.

"Lopez would make players look bad," he said. "He’d wait until a guy got out to the field, then send someone to replace him. I never played with a manager that made players do those things."

The All-Star Experience

Maxwell made it to two All-Star games (1956-1957), but described it as underwhelming compared to today’s spectacle.

"It wasn’t one of the highlights of my 14 years in the majors," he admitted. "There were no parties, no cocktail hours—nothing for the players except playing the game. By the time the game was over, most of the regulars were gone. It didn’t feel like an All-Star Game looking back."

Retirement and Life After Baseball

By the time Maxwell retired at 37, he knew it was time to move on.

"You know because you aren’t quick enough with your hands," he said.

While he believed he could have extended his career as a designated hitter, the role didn’t exist at the time.

"Back then, if you couldn’t play regularly, they didn’t want you."

Maxwell transitioned into business, finding success and fulfillment in manufacturing.

"I enjoyed competing in the business world," he said. "Even today, I can’t watch a game more than an inning or two. I have other interests. I got tired of competing in sports and enjoyed competing in business instead."

"I enjoyed my time in baseball, but I’ve enjoyed life after baseball just as much."

29 December 2024, 4:06 pm - How Chase Budinger Made The Transition From NBA Star To 2024 Beach Volleyball Olympian

Chase Budinger at the 2018 AVP NYC Open / Mpu Dinani

Chase Budinger at the 2018 AVP NYC Open / Mpu Dinani

Fans watching the 2024 Paris Olympics see a familiar face in Chase Budinger, but playing in a less-than-familiar arena on the sand. The NBA veteran made the switch to beach volleyball in 2018 after seven-year NBA career, focusing on making the Olympics in his first love, beach volleyball.Below is a 2018 interview I conducted with Budinger in New York City, just as he started on his Olympic journey. We discussed his transition, as well as how he was tested guarding LeBron James and Kevin Durant, both who have joined Budinger as 2024 Olympians.

Making The Switch

Entering this year’s AVP Gold Series in New York City, there was a big question mark as to whether Chase Budinger was truly ready to compete at the top tier of professional beach volleyball. Skeptics were weary of the 6’7″ California native, as he just returned to the sand this winter after capping a seven-year NBA career—as well as a season playing in Europe.

Spending the weekend playing alongside two-time Olympian Sean Rosenthal, the pair came away with a fifth-place finish—led by Budinger flashing dominant stretches at the net both blocking and hitting.

“I had a good run,” Budinger said at the 2018 AVP Gold Series last weekend in New York City. “[I had] three great years at Arizona, seven years in the NBA, and one overseas professionally. This winter, I didn’t want to go back overseas, and pretty much Sean [Rosenthal] came calling. It was the right fit and the perfect timing for me to make the transition.”

For those inside of the volleyball community, Budinger’s prowess is of little surprise. He was one of the most lauded prep stars in California’s history. He was Volleyball Magazine’s 2006 National High School Player of the Year. However, he was also the co-MVP of the 2006 McDonald’s All-American basketball game alongside Kevin Durant. When it came time to choose a college, he could not resist Hall of Famer coach Lute Olson’s pitch to focus solely on basketball at the University of Arizona.

“I pretty much went to Arizona because of Lute Olson,” he said. “Looking at that team, I felt like I could play right away and he had high expectations for me. … My three final schools were Arizona, UCLA, and USC. If I chose the other two schools, I would have played both [sports] … At that time I pretty much put it in my head to get away from volleyball and focus on just basketball and see how far basketball could take me.”

Committing To Training

Once he committed to returning to his volleyball roots, Budinger leaned on Rosenthal’s two decades of professional beach volleyball experience for support. Training together for the past six months, Budinger has tried to soak up as much knowledge as he could while building their partnership.

“It has definitely been a learning curve for me,” he admits. “There has been a lot of learning on the fly just because it comes so quickly. We started in late January teaming up and practicing. For now, communicating is the biggest thing while working together at every practice just picking each other’s brain, me especially picking his brain.”

Even though it is early in the beach volleyball season, the duo are already showing signs that they will be a formidable team for the rest of the summer. At the first AVP stop in Austin, Texas, they lost both of their matches en route to a 13th-place finish. But just a few short weeks later in New York City, the pair had a breakthrough performance that put them within a few points of advancing to the semi-finals.

“Every tournament is going to be really helpful for us getting that game experience,” he said. “For me, it’s really just about repetitions and game experience. It seems like you play these guys over and over in the AVP. I am so new to these guys and they are to me, but eventually you’ll start getting some reads on these guys. Taking it all in, I knew this first year was going to be a lot ups and downs for me.”

In most professional sports leagues, a 30-year-old rookie would be far from prospect status. But in the world of beach volleyball, the top talents peak in their late 30s, with many competing well into their 40s. Budinger felt that he is right on time to make an impact on the tour.

“I want to play for a long time,” he said. “I think I started at a good time. I’m still young. Volleyball players can play for a long time in their 40s; that is at least another ten years for me. That is kind of the goal, to play for ten years. When I made the transition, I always knew that in the back of my mind that I wanted to go back to volleyball and the only way that I was going to permit it was if my body could hold up. I think I came here at a time when I am still athletic, still can jump, and still can play.”

Guarding The Greats

Budinger’s showing in New York City came on the heels of the Golden State Warriors winning the NBA championship. Playing as a small forward in the NBA, he had the daunting task of guarding both LeBron James and the aforementioned Kevin Durant. Taking a moment to reflect on how he approached defending both superstars, he explained the nearly impossible task of stopping them.

“They’re un-guardable,” he admitted. “I had to try to guard Kevin and LeBron. Those two guys are just unbelievable. Durant, the way he could handle the ball, it is just unreal for being 6’11”. His handle makes him everything, just how he could cross people up, get into the lane and get to his spots. Once he gets to his spots, all he needs to do is jump and shoot over you and you can’t do anything about it.

“LeBron is just a bully. If he knows that he’s bigger than you, he’s just going to bully you and you can’t do anything. That’s what happened to me.”

So, does Budinger’s experience of going up against arguably two of the best basketball players of his generation transfer to the volleyball court? He said it’s another world where facing those legends earn you no points on the sand.

“It’s different,” Budinger says. “I just put my basketball days back and enjoy the memories I had from them. Out here, the energy is completely different. I will take all of the work ethic and approach that I learned over the years [playing basketball] to this game. But as far as playing against those guys, it doesn’t mean anything here.”

29 July 2024, 2:44 pm - Kusnick And Perfect Game's Legal Battle Raises Questions About NIL Rights

The issue of Name, Image, and Likeness (NIL) rights has become a hot topic in the sports world, especially in collegiate athletics. However, the conversation around NIL rights is also gaining traction in youth sports, particularly concerning organizations like Perfect Game. Sports agent Josh Kusnick, who is ensnared in a lawsuit with Perfect Game, shed light on the pressing need for reform in a recent interview.Perfect Game originally hired Kusnick to develop NFTs and consult for their expansion into trading cards and memorabilia. As talks soured, Kusnick went public with his dealings with Perfect Game. The amateur baseball giant sued Kusnick for defamation, claiming his statements affected their licensing deal with an immensely popular trading card maker.

We've got a new lawsuit involving trading cards to talk about! It's...well...basically Perfect Game v. Joshua Kusnick...and it's a defamation/libel/slander lawsuit.

— Paul Lesko (@Paul_Lesko) June 13, 2024

Who wants to do a (kinda) live-read of this?

(Kinda, because I skimmed it already) pic.twitter.com/DLM0q3RusyKusnick recently filed a motion to dismiss, with a lengthy 400-page document filled with revealing details he hopes will clear his name.

Conditional Participation and Inadequate Compensation

One of the most contentious issues is the conditional nature of participation in Perfect Game’s events. Kusnick highlighted Perfect Game forcing players to sign over their NIL rights as a prerequisite for participation. This practice not only exploits young athletes but also raises ethical concerns about commodifying children's talents.

"If you sign a permission slip and you go to a Perfect Game event, they can make stuff of your kid from that event,” Kusnick said. “So, like, if your kid's 12 and he becomes Mike Trout, they can make a card of him when he's, like, 12. They can make cards of 12-year-old you forever and not pay you for it."

Perfect Game NIL Release - Kusnick's Motion To Dismiss

Perfect Game NIL Release - Kusnick's Motion To Dismiss

The Value of Every AthleteKusnick stressed the importance of recognizing the value of every athlete, not just the elite performers. He challenged the notion that only standout athletes deserve compensation.

"Think about what that kid's worth to mom and dad, and that's what they're looking at,” he said. “Yes. And that's not me talking. No. I'm telling you; I was in those rooms. … The contributions of all athletes, regardless of their current skill level, are vital to the success of youth sports events. Recognizing and compensating these contributions is not just a legal obligation, but also an ethical imperative."

The Need for Reform and Transparency

As NIL rights gain recognition and legal backing, significant reforms are needed in youth sports organizations. Kusnick called for transparency and fair policies that compensate all athletes for their contributions.

"The absence of a robust NIL model in organizations like Perfect Game reflects a reluctance to adapt to the changing landscape,” he said. “The current approach, which requires athletes to sign over their NIL rights without compensation, is incompatible with the evolving legal and ethical standards of the sports industry."

Perfect Game’s Business Model: A Closer Look

Perfect Game's business model is another point of contention. According to Kusnick, the organization's revenues have historically come primarily from on-field tournaments. However, recent management shifts indicate a significantportion of their revenue now comes from other sources, such as merchandise and branding opportunities.

"When they took over, 95% of the business revenues came from the on-field tournaments, right?” he said. “That was the product and the model. Most of the money comes from the games, but then they started branching out.”

In Kusnick’s motion, he filed Perfect Game’s contract with Leaf, showing a $275,000 deal between the two companies for the trading card rights for Perfect Game’s events.

Leaf / Perfect Game Contract - Kusnick's Motion To Dismiss

Leaf / Perfect Game Contract - Kusnick's Motion To DismissAs these young athletes help to generate additional revenue for Perfect Game, Kusnick feels this is a situation where these players can no longer allow Perfect Game to exploit their talents.

"If 35% of your revenues are not on-field tournaments and it's advertising, baseball cards, bat companies and all the other stuff that you're bragging, I'm sorry, what is that called, then?” he said. “Explain that to me like I'm stupid, like you described in the first sentence."

Potential Privacy Concerns

Another issue Kusnick brought up in his motion, as well as our conversation, was access to personal information. He explained how anyone can purchase Perfect Game's Scout level plan for $799.99/yr to gain contact information for all Perfect Game athletes. While this information might be useful for scouts, Kusnick alleged this access is unchecked without a screening process, allowing any person willing to pay the fee to have address and phone contact data. This little-known feature opens a major question about privacy concerns with how Perfect Game does or does not protect their data.

Perfect Game Scout Access / Kusnick's Motion To Dismiss

Perfect Game Scout Access / Kusnick's Motion To Dismiss

Embracing a Fair Future

The handling of NIL rights in youth sports is at a critical juncture. Kusnick’s hopes this legal battle pushes organizations like Perfect Game to adapt to the changing landscape and implement transparent and equitable NIL policies.

"This is not just a legal obligation but a step towards fostering a fair and respectful environment for all athletes,” he said. “Embracing these changes is essential for ensuring a just and equitable future in youth sports."

15 July 2024, 1:40 pm - DJ Mark The 45 King Exclusive Mix From The Formula Radio Show With DJ Groove Da Moast

DJ Groove Da Moast

DJ Groove Da Moast

We take a short break from the baseball happenings to salute two hip hop pioneers, DJ Mark The 45 King and DJ Groove Da Moast. Sadly, both DJs died within a week from each other in October 2023, but we have this gem from The Formula Radio Show archives connecting the two legends.In February 2005, DJ Mark The 45 King was the show's featured guest, masterfully spinning exclusive tracks from his personal archives.

DJ Groove Da Moast (aka Fredy Blast) followed The 45 King with a tribute set of his own, expertly mixing up 45 King's classics. DJ Skeme Richards and Primetime provide the commentary in between the mixes, giving you a slice of the hip hop landscape at the time.

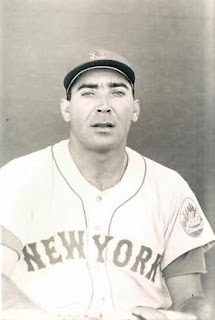

21 October 2023, 11:24 am - Roger Craig, 93, Helmed The Mound For Both The Dodgers and Mets In New York

Roger Craig, the split-fingered fastball master, who was part of Brooklyn's only World Series championship in 1955, died June 4, 2023 at the age of 93. The 12-year major league veteran later became the long-time San Francisco Giants manager from 1985-1992.

Roger Craig Throws Out First Pitch In 2012 At Citi Field / Mets

Roger Craig Throws Out First Pitch In 2012 At Citi Field / Mets

I wrote the following piece below for Metsmerized Online after interviewing Craig when he returned to New York in 2012 to throw out the first pitch at Citi Field. He celebrated his 50th year as an "Original Met" and relished discussing his playing career in both Brooklyn and Queens.Roger Craig holds a special place in New York baseball history lore, carrying the distinction of the first pitcher to take the mound for the New York Mets, as well as being a member of Brooklyn’s lone World Series championship team. At 89, Craig has outlasted nearly all of his peers that made the Brooklyn-heavy component of the 1962 Mets inaugural season.

Growing up in North Carolina, the lanky 6’4” pitcher faced a strong pull from another sport, basketball. He spent one year as a guard on North Carolina State’s freshman basketball team playing for the legendary Everett Case. While the opportunity to learn from a pioneer such as Case was tempting, it was not enough to compete with Brooklyn’s $6,000 bonus offer.

“I went to North Carolina State on a basketball scholarship,” Craig said. “When baseball season came around I talked to my dad [and told him] I wanted to drop out of school and play baseball and that is what happened. I dropped out and signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers.”

The Dodgers assigned Craig to their Class B team in Newport News to start the 1950 season. Still a teenager, Craig quickly discovered he was in well over his head.

“I was surprised they started me there,” he said. “That was a high way to start a young guy. I was 18 or 19. I started out in Newport News, and Al Campanis was the manager; I was really wild, and he sent me down to Valdosta, Georgia.”

With Craig in the modern day equivalent of rookie ball at Class D Valdosta, he was in the proper atmosphere for his skills to grow. Judging by how he explained it, his performance was far from perfect.

“I led the league in wins, strikeouts, base on balls, hit batsmen — everything,” he said.

While he was in Valdosta, Craig made the first of his Dodgers-Mets connections when he teamed up with a 20-year-old catcher named Joe Pignatano. He immediately noted the spark of his Brooklyn-born batterymate.

“Joe was a fiery competitor,” he said. “He went to the major leagues and became a great coach for a long time with the Mets.”

Before Craig could really mend his control as well as fortify his relationship with Pignatano, Uncle Sam arrived with a new uniform. The Army assigned him to a post in Fort Jackson, South Carolina, where he stayed for two years (1952-53) while many of his peers went overseas to Korea.

“The military really helped me because I was a basketball and baseball player,” he said. “All of my buddies went to Korea, and I stayed there and played sports. I had three catchers [who helped me], Haywood Sullivan, Frank “Big” House, and Ed Bailey. They said, ‘Kid, you have good stuff and a chance to play in the big leagues.’ They helped me, worked with me, and gave me a lot of confidence. I think I was 17-2 and 16-1 in two years down there.”

Just as Craig was to return to the Dodgers in 1954 after completing his military service, he suffered a cruel twist of fate that delayed his big league dreams.

“The day before I went to spring training, I was playing basketball to keep in shape,” he said. “I intercepted a pass, and a guy bumped me; I fell and broke my left elbow. I happened to have a family doctor; I talked to him and told him I had to go to spring training tomorrow. I told him to put an ace bandage on it and let me go to spring training. Finally, I talked him into it. I went to spring training and did not tell anybody for a week or two.

“Finally, Al Campanis came over, grabbed my left arm, and squeezed it. He said, ‘What the hell is wrong with you?’ I told him the fracture was small but had gotten bigger since spring training. When I played catch with my catcher down there, I told him not to throw the ball back too hard because I had a sore hand. If they threw it too hard, I’d let it go.”

His injury set off a true season beating the bushes, as Craig bounced around three teams in the Dodgers organization. He finally settled in with their Class B team in Newport News for the majority of the 1954 season.

With his impressive performance for Newport News in 1954, the Dodgers promoted Craig to their Triple-A team in Montreal for the 1955 campaign. After breezing through the league with a 10-2 record, Craig received a call to meet with his manager while the team played a series in Havana, Cuba. What happened next not only was a shock for Craig, but also for another of his future Hall of Fame teammates.

“When I got called to the big leagues, Tom Lasorda and I both pitched a doubleheader and [we] both pitched shutouts,” he said. “The next morning, the manager Greg Mulleavy called me in his office in Havana, Cuba. I said, ‘What the heck is going on? I went out and had a couple of beers.’ He said, ‘You’re pitching Sunday.’ I said, ‘I know, you already told me that.’ He said, ‘You’re pitching Sunday in Brooklyn!’ What a shock. Tommy was upset because he didn’t get called up.”

Pitching in Ebbets Field on a Sunday, Craig led the Boys of Summer to a 6-2 complete game victory. The man who went to North Carolina State with visions of hoop dreams was now standing tall on the mound as Brooklyn’s newest favorite son.

“When I first walked in that clubhouse with Jackie, Pee Wee, Duke, Furillo, and all those great Hall of Famers, I said, ‘I don’t belong here, what am I doing here?’” Craig said. “They made me feel welcome. I was lucky enough I pitched the first game of a doubleheader we played and beat Cincinnati with a complete game three-hitter victory.”

The Dodgers kept Craig on their roster throughout the rest of the regular season and the postseason. With the 1955 World Series knotted at two games apiece between the Dodgers and the New York Yankees, Dodgers manager Walter Alston called upon the rookie to give them the edge in the series.

“About the World Series, I pitched pretty well all year,” he said. “We lost the first two and won the next two. I told Joe Becker the bullpen coach, ‘I’ve gotta throw some.’ After I had thrown about ten minutes, he told me, ‘Sit down, you’ve had enough.’”

Craig did not immediately understand why his coach told him to stop throwing. That evening, after the Dodgers Game 4 win, Walter Alston made it evident why they wanted him to rest.

“He didn’t tell me then, but Walter Alston called and told him to sit me down,” he said. “We win the game. I go to the clubhouse, sit in front of my locker, and Alston walked up and said, ‘How do you feel?’ I said, ‘I feel great, I haven’t pitched.’ He said, ‘Well you’re starting tomorrow!’ I think Newcombe and Erskine were ready to pitch. I pitched six innings and we ended up getting a win. That was a great thrill.”

Fifty-seven years later when the Mets invited Craig to throw out the first pitch in 2012, all of his memories of World Series victory came screaming back as he toured New York City.

“My wife and I were here in New York and I threw out the first pitch for the Mets because I pitched the first game 50 years ago,” he said. “We stayed in Times Square and I remember the night I won my World Series game — my mother was there, my brother and my wife were with me, and I was on a TV show with Floyd Patterson.”

“After the show was over, we went to Jack Dempsey’s restaurant. He found out I was there and he sat down and talked with me. We came out and they had that big display in Times Square with the names going across it. My brother said, ‘Look up there, ‘Roger Craig beat the Yankees.’ It had my name up there. They got a big kick out of that.”

As the Dodgers emerged victorious over the Yankees to bring home Brooklyn’s first and only World Series championship, the young rookie was unaware of the moment’s significance. While he and the other upstarts were celebrating with hollered emotions, Craig noticed something different with the veterans.

“One thing about after the game was over, we were in the clubhouse and everyone was celebrating and drinking Schaefer and Rheingold beer,” he said. “All of the young guys, Roebuck, Bessent, Spooner, and myself were having a good time. You looked around, and all these guys, Jackie Robinson, Don Newcombe, Pee Wee Reese, and Duke Snider had tears in their eyes. I just realized that they had not won in so long and it was the first time they ever won it.”

“To get to this point and all, they all got very emotional. It was really something to witness. We just quieted down and let them be themselves.”

Craig stayed with the Dodgers as they moved from Brooklyn to Los Angeles. As one of the newer players on the Brooklyn team, he did not have the same attachment as his teammates who had planted their roots over a decade earlier.

“I was a young rookie and all that,” he said. “I was such a young guy and didn’t really see the total impact of guys like Gil, Erskine, Newcombe, Duke, and Campanella. A lot of the other guys did not want to leave. I am surprised that some of them even went.”

As he reflected further on the move, Craig realized how both National League teams’ westward migration opened the door for fresh New York Mets allegiances.

“I read the book O’Malley wrote about all the things he went through to build a stadium,” he said. “It was a bold move to do something like that. He talked Stoneham into going with the Giants. To move two clubs —that is why the Mets had such great fans. The Giants and Dodgers fans did not want to be Yankee fans. They were great Mets fans and it helped.”

As the Mets tried to capitalize on those nostalgic hopes that Craig noted, he and Gil Hodges were amongst the many former Dodgers that the Mets selected in the 1961 expansion draft. As sentiment has grown for Hodges’ Hall of Fame induction, Craig shared what made his late teammate special.

“He was the nicest individual I ever met in my life, on the field or off the field,” Craig noted. “He was a real professional and a gentleman. I could see why he was a great manager. He was a great hitter, but also probably, the best defensive first baseman I have seen. He was a catcher too; he could catch if he wanted to. He would have pine tar over his hands all the time. I would take a brand new ball and throw it over to him, he would rub it one time and it would have pine tar all over it. Sometimes the cover would be loose because he had those big strong hands. He was a great guy to play with.”

Craig was a mainstay in the Mets rotation during their first two seasons, pitching in 88 games, 27 of them complete games. He played an additional three years afterward, wrapping up his 12-year major league career with the Philadelphia Phillies in 1966. While he took the brunt of 46 losses with Mets, often with little to no run support, he still found happiness being in the company of familiar faces.

“It was like you had gone to a new team and all that, but with all those guys that played with Brooklyn and Los Angeles, it wasn’t that bad,” he said. “We just kinda had the good camaraderie right away, Don Zimmer, Gus Bell, Frank Thomas, Richie Ashburn, Hobie [Landrith], Felix Mantilla, etc. You think with those names that we would have won more games than we did, but it just didn’t happen.”

5 June 2023, 2:35 am - Fred Valentine | Washington Senators Outfielder Dies At 87

Fred Valentine, former major league outfielder with the Washington Senators and Baltimore Orioles, died December 26, 2022 in Washington D.C. He was 87.Valentine grew up in Memphis, Tennessee, where he excelled at Booker T. Washington High School in both baseball and football. A star quarterback and shortstop, he drew interest from multiple major league organizations out of high school; however, he decided to pursue his education at Tennessee A+I (now Tennessee State University).

At his college football coach's behest, Valentine chose to sign with the Baltimore Orioles in 1956, despite offers from NFL teams.

Like many Black players in his era, Valentine endured Jim Crow segregation in the South while playing in places like Wilson, North Carolina. Minor leaguers frequently received gifts from local businesses for stellar play. When Valentine went to collect his rewards, he was instantly reminded of the inequities he was fighting to escape.

"When I won something," Valentine said in Bob Luke's Integrating the Orioles, "which I did often, I couldn't go in the front door. I'd have to go around back. If it was a meal, they'd box it up for me."

Valentine persisted in the minors, receiving a call-up to Baltimore in 1959. He joined a select group of major leaguers who played through MLBs first decade of integration. His time with Baltimore was short-lived, as he spent the next four seasons at AAA trying to work his way back to the big time.

He caught his big break in 1964 when the Senators purchased his contract from the Orioles. Valentine's hustling spirit drew manager Gil Hodges' favor, something that resonated with Valentine over 50 years later when discussing his late manager.

“The biggest thing I remember from Gil was that when I came [to] spring training, the only thing he asked was for 100 percent," Valentine said in 2018. "Regardless of how the game turned out, he just wanted a hundred percent from his players, and I always felt I didn't have any problems with that. He was going to give me an opportunity to play, and I told him I was going to give him a 110 percent, and I think I did.”

Valentine played with the Senators through 1968, even earning MVP votes in 1966. A midseason trade returned Valentine to the Orioles to finish his major league career. He played one more season in the minors in 1969 and then spent the 1970 season playing for the Hanshin Tigers in Japan.

In retirement, Valentine worked with a group of former major leaguers to establish the Major League Baseball Players Alumni Association in 1982. He remained active in many charities, including the Firefighters Charitable Foundation, where he was an annual guest at their dinners and golf outings.

28 December 2022, 1:58 am - Randy Savage | 'He Was A Pretty Darn Good Little Catcher'

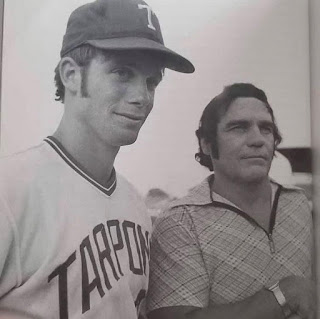

In 1971, Mike Vail and Randy Poffo were anonymous teenagers at the entry level of the St. Louis Cardinals farm system, eagerly trying to navigate the murky depths of professional baseball. Both would go on to garner national attention for their athletic feats. However, only one of them made their calling on the diamond. At the time for Vail, it wasn’t immediately clear that they would each experience success in different arenas.

“We were both real young, 18-19 years old,” Vail said during a recent phone interview in New York. “Randy, strictly from a baseball standpoint, I thought he was a pretty darn good little catcher.”

The Randy who Vail praises for being a quality receiver is better known to sports fans as WWE Hall of Famer “Macho Man” Randy Savage. During their summer as teammates, the younger Poffo outpaced Vail in both batting average and home runs. His later turn to a wrestling career caught Vail by surprise.

“We were roommates when we first came in with the Cardinals,” he said. “We kinda grew up together. It was interesting that he became the wrestler he was. It was kind of funny to see him become a wrestler; I thought he would continue on in baseball, but I guess he decided to go another way.”

As they pursued separate paths, the two lost contact, with Vail loosely following Poffo’s wrestling exploits from afar. A conversation with a teammate about the recent passing of former Tidewater Tides general manager Dave Rosenfield reminded him of a missed connection with Poffo, who died in 2011.

“It’s like so many other things in life,” he said. “You go to places and you do things … I was just having breakfast with Buzz Capra. We just lost a person who was close to us and a lot of people in baseball, our AAA general manager for many years, [Dave] Rosenfield. That came as a real shock to me and I wanted to go meet him and I didn’t have a chance to do it. It’s kind of the same thing with Randy. It was a shame.”

Vail made his own headlines during his 1975 debut campaign with the New York Mets, setting both a team and National League rookie record with a 23-game hitting streak. His National League record stood for a dozen years until Benito Santiago eclipsed it in 1987. The streak was all part of a whirlwind that came shortly after debuting in the heart of the Big Apple.

“It was like a dream,” he said. “It was amazing to be in the majors to begin with coming from AAA, like a little kid’s dream, to come to New York City. I tell people this all the time, the first day that I reported, Willie Mays was in the clubhouse. As a boy in San Jose, California, we used to watch Willie Mays, McCovey, Cepeda, Marichal … all of the greats back then that I grew up watching at 8-9 years old. Now I get to New York and Willie [Mays] was a coach for me. It was unbelievable. The tips he gave me were just amazing that he helped me with.”

Vail spent ten seasons in the major leagues, compiling a .279 lifetime average for seven franchises. Despite spending only three seasons in Flushing, his return to New York for a public autograph signing brought back strong ties to the city for the 65-year-old former outfielder.

“New York will always be my favorite town and team because I came up with the Mets,” he said. “I’ve got mixed emotions. I came here and was here for such a short time really in my estimation. I was planning to be on the team for quite a bit longer, but I had that bad injury in the off-season trying to get ready for the next season. It’s just mixed feelings; sometimes I guess I’m a little harder on myself than the fans are, wishing that [the injury] didn’t happen. I was hoping to be a bit better for New York than I was.”

* - Originally published April 14, 2017 for The Sports Post.21 December 2022, 6:25 pm - Dave Hillman | Oldest Living Mets and Reds Player Dies At 95

Darius Dutton “Dave” Hillman, a former major league pitcher and the oldest living member of the Cincinnati Reds and New York Mets, died Sunday, November 20, 2022 in Kingsport, Tennessee. He was 95.In eight big-league seasons spanning from 1955-1962, Hillman pitched for the Chicago Cubs, Boston Red Sox, Reds and Mets, compiling a won-loss record of 21-37 with a 3.87 earned run average.

Hillman’s best season with the Cubs was in 1959 when he posted an 8-11 mark and 3.58 ERA, completing four games and pitching seven or more innings in nine others. He tossed a two-hit shutout against the Pirates; struck out 11 in seven innings of relief to beat the Los Angeles Dodgers; and in the next-to-last game of the season stopped the Dodgers in their bid to wrap up the National League pennant. The Dodgers were one game ahead of the Milwaukee Braves with two to play. A win over the Cubs and Hillman clinched a tie.

“I went out there, honey, and I’ll never forget the control that I had,” Hillman recalled. “I could thread a damn needle with that ball. I was just sitting back and sh-o-o-o-m-m-m…throwing that thing in there.”

Hillman scattered nine hits and struck out seven in the Cubs’ 12-2 win. The Dodgers ended up beating the Braves in a playoff and winning the World Series. It took Hillman six years to work his way up through the minors to the majors.

Dave Hillman (r.) with Ernie Banks (l.) / Author's Collection

Dave Hillman (r.) with Ernie Banks (l.) / Author's Collection

He started his professional baseball career in 1950, winning 14 games at Rock Hill, South Carolina, in the Class B Tri-State League. He won 20 for Rock Hill in 1951, one of them a no-hitter. He also led the league in strikeouts with 203.Hillman won only eight games the next two seasons, but he notched another no-hitter in 1953, playing for the Springfield, Massachusetts, Cubs in the Class AAA International League. A 16-11 record in 1954 for a seventh-place team, Beaumont, Texas, in the Texas League, earned him a shot with the Cubs.

A sore throwing arm nagged Hillman in 1955 so the next year the Cubs sent him to their Pacific Coast League affiliate, the Los Angeles Angels. Despite missing the first month of the season, his 21-7 record, 3.38 earned run average, three shutouts and 15 complete games paced the Angels pitching staff.

“Dave Hillman was Mr. Automatic,” said Dwight “Red” Adams, a ’56 Angels teammate who went on to become a highly respected pitching coach for the Dodgers.

After the 1959 season, the Cubs traded Hillman to the Red Sox in Major League Baseball’s first inter-league trade. He pitched primarily in relief for the Red Sox in 1960-61 before ending up with the Reds and Mets in 1962.

Hillman appeared in 13 games for the Mets, with no decisions, one save and a 6.42 ERA. When the Mets optioned him to the minors in late June, he headed home to Kingsport to work in a men’s clothing store owned by an uncle. He figured selling shirts and shoes was better than being with the hapless Mets and getting kicked in the pants every time he pitched.

Hillman was born in Dungannon, Virginia, on September 14, 1927, the fifth of seven children. He married his high school sweetheart, Imogene Turner, in 1947 and relocated to Kingsport in 1952.

Hillman is survived by a daughter, Sharon Lake of Portland, Tennessee, three grandchildren and six great grandchildren. His wife, Imogene, died in 2011 and their son, Ron, in 2017.

*This obituary was written by author Gaylon H. White, who featured Hillman in his book, The Bilko Athletic Club: The Story of the 1956 Los Angeles Angels.

21 November 2022, 12:02 am - Ted Schreiber, 84, Mets Infielder Made The Final Out At The Polo Grounds

.jpg)

Ted Schreiber experienced every Brooklyn boy’s dream, making it to the major leagues with the New York Mets in 1963 after playing at James Madison High School and St. John’s University. While Schreiber’s MLB career lasted only one season, he represented a rich lineage of ballplayers who cut their teeth at the Parade Grounds on the way to the pros. Sadly, Schreiber died September 8, 2022, at his Boynton Beach, Florida home. He was 84.Born July 11, 1938, Schreiber grew up a Brooklyn Dodgers fan, admiring legends like Duke Snider who would ironically become his teammate on the Mets. Schreiber first cut his teeth playing softball, only picking up baseball at age 15 when he attended high school.

At Madison, Schreiber was a multi-sport star, garnering St. John’s attention in both baseball and basketball, the latter in which he earned All-City honors. At St. John's, Schreiber continued playing both basketball and baseball. With the help of Jack Kaiser’s connections, he signed with the Boston Red Sox in 1959 for a $50,000 bonus spread out over four years. While in the Red Sox’s minor league system, he played with fellow New Yorkers Carl Yastrzemski and his Manhattan College rival Chuck Schilling. Schreiber quickly realized Schilling was blocking his path to the show and rejoiced when the Mets selected him in the Rule V draft at the end of the 1962 season.

As a second baseman, Schreiber faced intense competition on an otherwise hapless Mets team. He told author Rory Costello how Charlie Neal made sure the Brooklyn kid was on the field enough to gain manager Casey Stengel’s favor.

“I never had a rabbi with the Mets,” Schreiber said. “Larry Burright had Lavagetto. Ron Hunt had Solly Hemus, though I’ve got to say, he was a really good ballplayer. Another thing against me was that the Daily News and Journal-American were on strike that spring. They might have backed the local boy. If it wasn’t for Charlie Neal giving me some time in spring training, I wouldn’t have had a chance.”

Schreiber made the team out of spring training, but sparingly saw the field. After appearing in only six games, the Mets sent him down to the minor leagues where he could get more playing time. The Mets recalled him in July and remained with the club in a reserve role for the remainder of the season.

On September 18, 1963, Schreiber made history when he played in the final MLB game at the Polo Grounds. The Mets squared off against the Pirates in front of a sparce 1,752 spectators. Pinch hitting in the 9th inning, Schreiber hit a ball he was sure would evade Cookie Rojas’ glove. Rojas turned it into a double play that was the final two outs at the famed stadium.

“Sure, I remember the game because I made the last two outs,” Schreiber told me in 2011. “I thought I had a hit because I hit it up the middle, but Cookie Rojas made a great play on it. … That’s why I’m in the Hall of Fame; they put the ball there because the stadium was closed after that.”

Schreiber tried to hang on in the Mets farm system, but he chose to follow a teaching career which limited his availability to the summers. After doing double duty at Triple-A in 1964 and 1965, Schreiber decided to trade his cleats for chalk as a New York City teacher.

Perhaps Schreiber’s most significant legacy didn't come in a Mets uniform, but was the 27 years he spent as a math and physical education teacher at Charles Dewey Middle School in Sunset Park. He lived in Staten Island until his retirement, moving to Centerville, Georgia, and then settling in Boynton Beach until his passing.

*ed note - Rory Costello has been attributed to the Charlie Neal story.

18 September 2022, 12:29 pm - Ed Bauta, Cuban Pitcher With The New York Mets and St. Louis Cardinals, Dies At 87

Ed Bauta, a former Cuban pitcher with the St. Louis Cardinals and New York Mets died July 6, 2022, at Southern Ocean Medical Center in Manahawkin, New Jersey. He was 87. With Bauta’s passing and the recent deaths of Leo Posada and Cholly Naranjo, only a few players remain who played in the Cuban Winter League prior to Castro’s takeover.The 6’3” right-handed pitcher grew up in the town of Florida in Cuba’s Camagüey province. He caught Pittsburgh Pirates scout Howie Haak’s attention at a 1955 tryout in Camagüey and was later signed to the Pittsburgh Pirates with a $500 bonus.

Toiling in the low minors, Bauta returned home to Cuba, but couldn’t latch on with one of the four major teams. “I tried out, but they sent me home,” Bauta said in 2011.

He trained with Marianao as a reserve, but never saw any regular season action. Finally, after a strong showing in A-ball in 1958, he earned a spot on the team. He pitched the final three seasons of the Cuban Winter League, finishing the 1960-61 season with Havana.

“I finally played with Marianao for two years and then ended up with Havana,” he said. “Everybody’s salary was cut in two to help the revolution [the final season].”

Sadly, Bauta had to make the decision, like many of his Cuban brethren to leave his family behind in Cuba after the 1960-61 Winter League season.

“My family house was gone,” he said. “I had a few dollars in the bank and that was gone too.”

Stateside, Bauta continued to make strides towards the major leagues. When the Pirates traded Bauta in 1960 to the Cardinals with Julian Javier, it opened the door for Bauta to make his major league debut. He stayed with the Cardinals for the rest of the 1960 season.

He shuttled between the majors and the minors the next two seasons with the Cardinals, before being traded to the New York Mets for Ken MacKenzie in August 1963. The late-season acquisition allowed Bauta to be a part of Mets history, pitching in the final game at the Polo Grounds on September 18th. The game was played to little fanfare and Bauta didn’t recall much about the game during our 2011 conversation.

Bauta was also connected to another bit in Mets history, as he was the losing pitcher in the first game at Shea Stadium. He came in relief of Jack Fisher in the 7th inning, but couldn’t hold the 3-2 lead, giving up both the tying and go-ahead runs. Less than a month later, Casey Stengel sent Bauta to the minor leagues. It didn’t sit well with the Cuban reliever.

“In 1964, I only pitched eight games,” he said. “They sent me down to Buffalo. I went 8-4. They didn’t send me back up. I got pissed off and quit.”

Bauta never reached the majors despite pitching in the minors and the Mexican League until 1974. He worked in the moving business until 1988 before retiring due to knee problems. In retirement, Bauta kept close contact with fellow Mets and Cardinals pitcher Craig Anderson.

“He knows everything about baseball,” he said. “He’s a hell of a guy.”

At the time of our talk in 2011, Bauta also shared the news of his MLB annuity payments. The union agreed to make annual payments to non-vested players who were on MLB rosters at least 43 days before 1979. While Bauta played in parts of four seasons, he did not play long enough to vest for a pension. He welcomed the extra money.

“We’re really happy about it,” he said.

9 July 2022, 3:58 pm - More Episodes? Get the App