- DRUGS'N'SUGAR: SHOULD WE FEAR THE HOME-BREWED OPIATES?Can you make heroin in your back garden? until recently the answer would have been an unequivocal no. However, independently of each other, two recent articles may change all this. Researchers have genetically engineered strains of yeast that can take simple sugars and produce the molecules necessary for opiates, mimicking how poppies currently do this. Listen to our podcast here:

https://ia601508.us.archive.org/7/items/Drugssugar2/drugs&sugar%202.mp3

Currently, the only commercial way to produce morphine and other opioid analgesics such as oxycodone is to farm the opium poppy. To attain high enough yields this crop must be grown under highly regulated conditions that are tenable in only a select number of countries. These difficulties make it quite difficult to cultivate illegally, which acts as a minor check on the availability and distribution of opiate-derived drugs; however, difficulty of production may also hinder the production and availability of cheap opiate-derived analgesics. Thus, the development of a novel mechanism for opiates may not be unequivocally good.

The opiate-synthesis pathway is long and non-trivially difficult to emulate given there is no whole genome sequence of the opium poppy, which makes all the enzymes required difficult. The solution was then to find a plant or an insect or even a human model that could be coaxed into producing the desired reactions - so far this does not exist in one organism. However, Dueber and colleagues show that you can get the half of the way there by having yeast produce an intermediate compound (reticuline). In combination with a similar paper published in April showing how to get the second half, we are now well on our way to producing opiates in yeast.

We should say however, that the authors themselves admit that there will still be a while until these two strains are combined into one, and even then there will still be work to make the fermentation process efficient. However, once these are completed they suggest that anyone with this strain would be just as able to brew their own beer as to make their own morphine.

The benefits for improving the production of opiates are clear - it could lead to more efficient and cheaper painkillers that may indeed have fewer side-effects such as addiction. However, the detriments are also clear - it may make the production of heroin cheap and localised, and in turn make it easier to produce in simpler facilities more widely distributed globally.

In response to these concerns, authors have been discussing the bioethical issues with Kenneth Oye at MIT. It is important to remember that the goal is to create a legal framework for research into these compound producing organisms that preserves important research into drug development while not increasing the risks for a boom in the illegal opium trade. Unfortunately, the current regulatory framework focuses on pathogenic organisms such as smallpox or anthrax, and so are not prepared for these advances.

The regulatory recommendations from these advisers are as follows:

- We could develop a yeast strain that would produce opiates less attractive to criminals (thebaine); or a strain that is artificially difficult to cultivate outwith an industry standard lab, such as is done with E coli; or we could insert a DNA watermark to allow easy identification of strains by law enforcement.

- We should keep the strains under lock and key away from criminals.

My own opinion of these recommendations is that most will not be specific to the current solution and so fail to address the uniqueness presented by this advance in synthetic biology. This is with the exception of having a genetic watermark on the strain, which may be a more honest strategy that accepts the strain will likely be adopted by illicit trade but hopes to allow itself to act retroactively to stop it.

After all of this though we should remember that the researchers themselves are excited scientists that are finding out that we can step outside of what evolution has provided us with and will soon be at a veritable pick and mix for what we can make. The real value of these methods will, they say, not be the more efficient synthesis of things we already have, rather the iterative augmentation of collections of compounds to make new and beneficial compounds in the medical sciences.

Related article : http://www.nature.com/news/drugs-regulate-home-brew-opiates-1.17563

Correspondence & blogpost (this topic) : KSB Editing : EK

12 June 2015, 6:20 am - SEX IS ALWAYS COMPLICATED, OR CAN YOU REALLY KNOW IF YOU ARE A BOY OR A GIRL?

You walk into a bar on a night out in search of an individual to lay your eyes on, whichever sexual orientation you may be, a key strategy in your search will be singling out the sex of the target of your affection. Asked on the street, most would surely say identifying male from female is not a difficult task, however, recent research suggests that our long held belief that sex is dichotomised is in fact a fallacy. Typically, we think of sex as defined by the presence or absence of two X chromosomes, simple; yet, a cohort of extreme cases with disorders of sexual development, such as with transsexual persons with abnormal genitals, have shown physicians that we may walk the line of male/female sex.

Delimiting male and female becomes more than a complex question of how to raise a transsexual child when we consider the genetic data underpinning this boundary (For the review paper, click here). For instance, a case study of a woman receiving a test for genetic abnormalities in her foetus found that although her baby was fine, she was composed of two distinct groups of cells, one male and the other female – only in her late forties had she discovered she was perhaps not entirely female! These finding are increasingly common and lead to the conclusion that we are a cellular patchwork quilt of genetically heterogeneous cells. What is more interesting is that there is some evidence to suggest that the sex of these cells may be informative for function and behaviour. These microchimaeric cell populations appear in mice models not be idle in their "foreign" environment, and infant adapt and adopt specialised functions for the host. Unfortunately, it is, as yet unknown whether these sex differences have a deleterious effect on the tissue behaviour, sexually dimorphic immune responses, for example.

However, my immediate question is “is this just another academic nicety, or does this variation actually have an impact on how we should understand physiology?”. One answer is, yes, regardless of these cellular variations, there is a very well-understood process from foetus to baby that defines whether a child will one day carry a baby to term or will just contribute the building blocks in the form of sperm.

Yet, even the common belief that we are born female and develop from there in to males from a series of endocrine cascades has recently been challenged. Although initial findings of the SRY gene that alone may induce testicles to develop over the seemingly default ovaries, recent genes that actively suppress testicular development and favour ovaries call this into question. This subtle genetic trade-off appears to paint a more complex picture than we may expect, more of a battle between the male and female phenotypes.

We might expect that the male and female phenotype struggle against each other in early, in utero, development, or even perhaps for some sensitive period in early life, however, it is possible that the battle of the sexes persists long into adulthood. Evidence from mice studies show that by activating or deactivating a particular set of genes, the cells that initially supported the production of female eggs transform to those cells that produce sperm and visa versa - we can see post-natal cell regulatory effects on the sex of our physiology! Yet, this may not be as shocking as you or I first perceive it; there are epigenetic (within-lifetime genetic regulatory) effects in at least 25 genes typically associated with disorders of sexual development, found in "normal" individuals, which suggests that even for the average person sex is on a continuum, and that differences need not be as dramatic as in disorders such as hermaphrodites. Nonetheless, it will often be the shocking examples, such as the elderly man who discovered at the age of 70 that he had womb!

If we step back a little form the catchy headlines for a minute these finding present a profound question "can we assume that each cell contains the same set of genes"? A core tenet of even high school biology, it appears this may not be the case! In fact, this may be the take-away point of the question of sex defined as binary. However, we should also ruminate on the social implications of sex as a spectrum. What will it mean if this line of research gains enough momentum to make us truly question what it means to be female or male; must we then alter our attitudes on the questions of equality; should we re-examine the legal and cultural boundaries that centre on what seems an immovable basis of our understanding of ourselves? Whichever we choose, what exists in the literature at present is at the very least food for thought, but I hope it has made you question how you think of sex!

Listen to our podcast here:

https://ia601506.us.archive.org/7/items/SexRedifined/sx.mp3

17 March 2015, 11:29 pm - SELF-PHONE: DO WE INCORPORATE OUR MOBILE PHONES INTO OUR BODY SCHEMA?

Have you ever heard of nomofobia, a fear of not being able to check your phone regularly? Are you going crazy when forget your charger home? Have you ever freaked out because you reached an area without reception? Would you return and go home immediately because you left your phone home? You know what we are talking about. But is there an evidence for tools that we use regularly "grow" on us, furthermore, become the part of our body schema?

The way we perceive our body is crucial for knowing our place in the world. Literally speaking, the information from our joints and muscles provide the baseline to coordinate our movements and actions. The so called proprioceptive set of stimuli arriving to the central nervous system is often not conscious, but always stored in comparison with other modalities such as visual information (looking in the mirror for eg.). This purely perceptive, on-line, plastic representation of our body is often referred to as 'body scheme' in neurology. The body schema is actually a working model, a helpful one, that can help anchor motor commands to the current position and state of the body. It is transient in nature, and its disturbance can lead extreme cases as described by Oliver Sacks (read on Oliver Sacks's terminal disease here):

In that instant, that very first encounter, I knew not my leg. It was utterly strange, notmine unfamiliar. I gazed upon it with absolute non-recognition […] The more I gazed at that cylinder of chalk, the more alien and incomprehensible it appeared to me. I could no longer feel it as mine, as part of me. It seemed to bear no relation whatever to me. It was absolutely not-me – and yet, impossibly, it was attached to me – and even more impossibly, continuous with me .

Oliver Sacks: A Leg to Stand On (1991)

Body image, however, is the conscious concept about our body, that is "on the surface", it is the summation of the attitudes towards our body, thats one object of the environment. This knowledge is highly semantic and is closely related to our cognitive (I am fat), affective (I am ugly) and behavioural (self-punishing behaviours) interactions with our own self. In fact, as Mahler claims, having a body image is one of the first steps of having a self by differentiating ourselves from our mother. (Longo et al, 2000).

But how can we connect all this concepts to what is actually happening in the brain? Neuroscientific research is mostly focused on the body scheme, since it is much easier to operationalize in primates. The concept of body map and somatotopic representation (A.K.A humunculus) is one of the first main findings of neuroscience, as it proves the premise of functional localisation in the brain. As Maravita and Iriki describes, the action-specificity of the body scheme (the fact that we fine-tune our movements compared to our position and previous movements) is pinned down to the frontoparietal network. More precisely, the receptive field of the neurons is "bimodal". For example, in a way that they respond with elevated firing rate to sensory and proprioceptive stimuli if it comes from the same "gestalt", the movement of the same limb or body part (interestingly that is not the case with fine movements, finger movement is encoded in a different way).

Macaque selfie - strangely relevant to this post

Macaque selfie - strangely relevant to this post

How can we answer body schema-related questions in primates? One clever way of doing it is via tool use: the macaques were put in cages where it was impossible to reach the food that was put outside of the cage, unless they used a rake to pull the food towards themselves. After several days, the neurons of the frontoparietal network, that initially responded to the hand-related visual or proprioceptive information expanded to the rake, but only if the rake was used to grabbing food (only if the ACTION was functional).

source : http://tinyurl.com/oa4x8mz

If you want to know how macaques and rakes can explain how you get anxious when your phone dies please listen to our podcast here !

Characteristic neglect-bias in a drawing task.

Characteristic neglect-bias in a drawing task.

See the podcast for further information

27 February 2015, 8:14 am - THE VAMPIRE APPROACH OF BRAIN REJUVENATION - A CURE FOR ALZHEIMER'S DISEASE?Sit back and listen to our podcast !!!!

Will baby blood hit the anti-aging market? Is the young blood transfusion the new omega 3 / golgi berries for the prevention of cognitive decline? Stanford and Harvard scientists claim so. A new wave of interest was drawn from an old, yet neglected medieval medical technique, where two circulatory systems, one old and one young, were connected in order to refresh the old brain and facilitate its healing and rejuvenating mechanisms. The method, now fancily called heterochronic parabiosis, has recently been brought back to scientific focus for one simple reason: it looks like its working.

source: http://tinyurl.com/qcr9bwy

source: http://tinyurl.com/qcr9bwy

The neurological decline and associated cognitive deterioration experienced during healthy ageing as well as neurodegeneration is one of the biggest mysteries in neuroscience. It seems like we cannot point out a single, culpable black sheep from the several factors that accounts for the progressive decline in the end of life. Rather, it is more likely that there is a cascade of "little things going wrong" that leads to the decline in overall performance. This is exactly why counteracting or slowing down this progress is not an easy task. It is not surprising that a method offering an all-purpose "cure" against old age will rob the bank, especially if it can have headlines such as Vampire therapy of ageing, and put Fifty shades of grey ads in the corner.

2014 was the year of young blood. I mean, apart from the season finale of True Blood, Katsimpardi and colleagues (2014) stitched an old and a young mouse together to connected their circulatory systems. This was not only beneficial for the vascularisation of the old brain compared to the young one but also upregulated the neurogenesis in one of the areas of the brain known for its role in the memory formation, the hippocampus. Pretty fascinating stuff, because it implies that we can now fight ageing in two ways: 1) better circulation in the brain (hence more food and oxygen to the neurons, and less probability of a stroke) and 2) more neurons in the area that is most likely to be the correlated with the contextual memory (decline). However, there is a rather big jump between the experimental evidence and literature review of possible candidate mechanisms to put behind all these effects. The authors finally pulled out the chocolate sprinkle (see the podcast) of growth factors called GDF11 to test on their parabionts. However, GDF11 is, according to my knowledge, too big a protein to cross the blood brain barrier (its concentration was not measured, it was only administered in the brain as a separate experiment). This does not mean that it cant account for a lot of circulatory beneficial effects, but I cant necessarily see the direct connection with the neurogenesis. The authors themselves highlight overall effects sayingThis suggests that neural stem cells exposed to young systemic factors increase their ability to proliferate and differentiate into neurons.

(highlighting by me if you cant tell form the shade of purple immediately :P)

Hhmmm...anyway... Are these newborn neurons functional parts of the network; can we correlate their operation with physiological and behavioural improvement? Stanford suggested that we can. This paper is an old-school, all rounder evaluation of the vampire approach, so much so that they are not even stitching the bellies together, just transfusing the serum of young mouse to older ones. Clever move, not just because it helps the PR part (stitching together old people with babies, not my dream advert for rejuvenation therapy), but it also makes the implementation easier. They also started by looking for the 'it' factor of rejuvenation by performing a genome-wide microarray analysis of the old and young hippocampi in the parabiont mice. They found a rather good chocolate sprinkle called Creb (cyclic AMP response element–binding protein), that is known for regulating game-changer proteins such as C-Fos (indirect correlate of neural activity), and to be essential for the sustenance of the good old LTP (see later). Now thats a start, but what else changed? If we compare levels of neuroscientific interest to a computer (dare I compare it to the brain itself), they found differences on all levels. If we take the hardware, they showed greater number of dendritic spines in the heterochronic parabionts in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampi, but not in another part (CA1). Sadly, the press was shouting Alzheimer, but in this neurodegenerative disorder, dentate gyrus stays intact for relatively long time. Does not immediately shout Alzheimer to me. Difference of all levels (1. experimental groups, 2. anatomical remodelling: more spines (hardware), 3. change the physiological correlate of synaptic plasticity, more sustained LTP in the control group (software) )

Difference of all levels (1. experimental groups, 2. anatomical remodelling: more spines (hardware), 3. change the physiological correlate of synaptic plasticity, more sustained LTP in the control group (software) )

source: http://tinyurl.com/qxhdm35

Anyway, the authors then addressed if there is anything upgraded in the software. They found that long term potentiation, the gold standard electrophysiological measure of long term memory function was maintained for the entire recording period in the old members of the old-young pairs compared to the aged members of the old-old pairs (controls). We all know how slicework in neuroscience is the bread and butter of describing causality, but we know nothing about what happened in vivo from all this. Lastly, the IT wants to know what happens if we give a new task to this computer, so the behaviour of the heterochromic parabionts vs controls was tested in many, hippocampus-related contextual memory tasks. This tasks are basically the rodent version of the where did I park my car last night kind of lifehacks. Surprise, surprise, rejuvenated old fellow mice did better than re-not-juvenated peers.

Now one last thought about this ... where is the evidence that it is a cure for Alzheimers??

Taken together, what can modern neuroscience say about the fountain of youth compared to the good old times? Not more than that we can actually prove the effect of young blood. Converging evidence supports the method is somewhat, somehow working. Exactly how my grandma argues for superstition and folk wisdom. It is still a good guess, we might as well give it a go, even without knowing the chocolate sprinkle factor of it. Even if we have no idea how to implement a huge amount of young blood transfusions on a longer term.4 February 2015, 7:35 pm - WHERE THE MAGIC HAPPENED

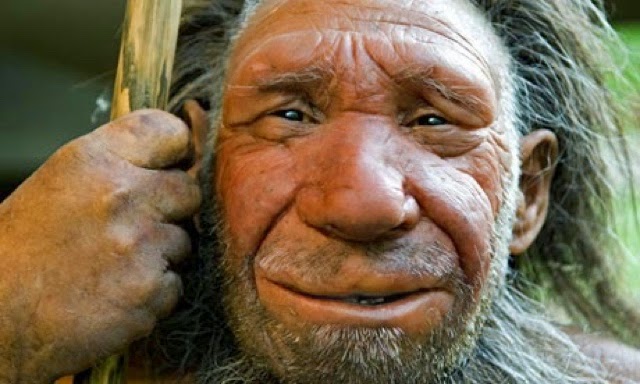

When and where did we first go to bed with our neanderthal cousins? A recent study in the journal Nature was reported in the media as having answered this with 'a cave in Israel and 55,000 years ago'. Given the importance of understanding our lineage and precisely how we migrated from Africa and spread and dominated through out the world, a finding reported like this should rewrite the text books - lets see whether the paper says what the media said, and whether it should!

The paper itself discusses the finding of a fragment of skull in a northern Israeli cave in western Galilee named Manot. The skull was dated at 54.7 kya plus or minus 5 kya using uranium-thoriam methods. The overall shape was unequvocally identified as anatomically modern humans. Lastly, this fragment represents the only fragment to date that can be colocated temporally and geographically with neanderthal specimens (neanderthals have been found as close as 24 miles from the Manot caves). That is it; that is all of the information in the paper that has been used to suggest that this piece of skull is evidence that we first mated with neanderthals in modern-day Israel approximately 55 kya - is that enough for you?

To give credit to the journal article, they do not declare so brasenly that their specimen identifies where anatomically modern humans interbred with neanderthals, rather, that it represents the current best guess. This is based on evidence from previous studies of the morphology of the skull (suggesting the general location or Europe) and genetic data that propose that it happened in a restricted area geographically about 50,000 - 60,000 years ago. In the context of these studies, finding a skull fragment in this location may seem reasonable evidence, but if we poke a little at the story is it a house of cards?

All this shows right now is that there were humans present and certainly not a thing about there behaviours. The limits of paleoanthopology technique, unfortunately, do not extend to describing with whom this particular individual interacted, their gender, or with whom he/she slept. Many such questions do not have definite answers that can be gleaned from small skull fragments, however, many of them can be addressed with genetic sequencing. Sadly, though, no such analyses have been done on this specimen. Without such genetic analyses it is not possible with great certainty to establish where this individual fits into the modern human family, let alone whether he/she mated with neanderthals and where in line they where.

All in all, the way this research was reported was a vast overexageration of what the paper reported, and unfortunately, the paper reads rather a lot like they are overexagerating what is a very nice finding. What should have been said is that a speciman, plausibly identified as human, was discovered at a geographic and temporal location that we believe would have been shared with neanderthals, which helps us better describe our migration out of Africa - no sex needed! Although that doesn't sound as compelling!

31 January 2015, 4:35 pm - THE HOUSE ALWAYS WINS AND CANCER HOLDS THE DEEDS ?

Is there really anything we can do to prevent cancer; are we better packing it up and conceding that at some point we will all succumb to the emperor or all maladies? A well reported paper by the media last week in the journal, Science, does appear to have suggested this, and is surely a rude surprise to cancer researchers globally (including myself)!

The paper in question found that 2/3 of the lifetime risk of developing cancer could be explained by only the random errors that accumulate overtime when cells replicate. This is indeed a shocking finding, but lets unpack it a little and see whether it is really saying all it has been reported as in the media - hint, it is not!

Recent article reports cancer is due to mostly stochastic errors in cell divisions.

Lung cancer, however, falls out of this category, hence it cannot be explained solely by the luck factor.

source :http://tinyurl.com/okdtt3w

Recent article reports cancer is due to mostly stochastic errors in cell divisions.

Lung cancer, however, falls out of this category, hence it cannot be explained solely by the luck factor.

source :http://tinyurl.com/okdtt3w

Firstly, the study accounts for 31 cell-types in its analysis and measured the association with the corresponding physiological location, a far cry from having considered cancer as a whole. In fact, common cancers such as breast or prostate were omitted. Explicitly, the study took stem cells (the basic building block for cells of all types) from these organs and estimated the number of cell replications that a particular organ would likely undergo in a single lifetime. The premise is that different organs will require different rates of cell replication just for the mainantance of the baseline function. Each time a cell replicates there is a certain probability that an error will occur that may or may not lead to cancer, and so organs that duplicate more should be more likely to observe cancer risk - and this is what they observed by correlating the estimate of cell replication with lifetime risk.

However, lets quickly remember an old adage "correlation does not equal causation". It is difficult to suggest that this correlation is anything more than a very plausible association, and it is certainly not appropriate to suggest that this correlation rules out factors that we can affect like diet and lifestyle. More skepticism should also be given to the result as it didn't include the most common cancers that would be household concerns like prostate and breast, and so suggesting as the media did that cancer as a whole is stochastic is wholly misleading - such descriptions of cancer as one homogenous entity is just flat out incorrect, and will I'm sure be the topic of a future post! We should note also that the study inferred mutation rates that likely lead to cancerous cells from the estimated number of cell divisions, and did not explicitly measure said mutations. While this is an acceptable method for a paper, it is so only in the knowledge that average mutation rates will not be useful for predicting individual cell DNA mutations, and further, not all mutations lead to cancer - so we cannot say that these cell replications will predict with a large degree of accuracy which cell will have which mutation, and whether it will be cancerous.

The final passage of the paper discusses how this correlation can be useful when deciding how to direct research funding and public policy. They use a clustering algorithm to group the cell types they used into two categories: largely driven by random mutations, and largely not driven by random mutations. The suggestion is that research should be directed to discovering modifiable risk factors (diet and lifestyle, etc) for only those cancers where they will be likely to be found. In the light of the caveats I raise with interpreting their findings, I hope it will not be a surprise that I am worried greatly by their claim that the single correlation should drive policy! Cancer is an umbrella term for a set of very complex and harmful diseases, and research should be driven by a more robust set of results with careful analysis than these.

For our podcast discussing this article look here: https://ia902600.us.archive.org/…/cancer…/cancer_podcast.mp3 !

Itunes channel: http://feeds.feedburner.com/Popscienceplease

28 January 2015, 9:27 pm - Ars Poetica A.K.A. Hello World!This is supposed to be a semi-serious blog linked to our podcast channel.

Find more info about us and our approach here.

For inspiration, we would like to quote Molly Crockett (how adorable is she and her name btw), from her amazing Ted talk, which can be seen here,

So what I'm going to do is to show you how to spot a couple of classic moves, dead giveaways, really, for what's been called neuro-bunk, neuro-bollocks, or, my personal favourite, neuro-flapdoodle.

I mean, the summary of our manifesto would be more like this (with minor modifications)

Ask the tough questions. Ask to see the evidence. Ask for the part of the story that's not being told. The answer should not be simple, because science is not simple. But that is not stopping us trying to figure it out anyway.

This comes here just because we wanted to stick on nice visuals, but

then Molly pointed out that its not nice to put a brain on it - it adds credibility.

Nevertheless, neurons are freaking amazing, and the image is a way more original than a schematic brain (#prouddphilstudent)

This comes here just because we wanted to stick on nice visuals, but

then Molly pointed out that its not nice to put a brain on it - it adds credibility.

Nevertheless, neurons are freaking amazing, and the image is a way more original than a schematic brain (#prouddphilstudent)

So, we hope that you agree with the first, in that there is quite a lot of trash out there, and the second, in that we should careful sift through to find the nuggets that are really meaningful examples of human endeavour.

Enjoy!

Eszter & Karl13 January 2015, 10:34 pm - More Episodes? Get the App