Missouri Botanical Garden - Welcome to My Garden

Missouri Botanical Garden

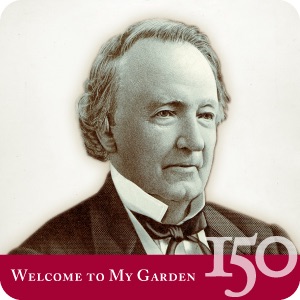

Founder Henry Shaw welcomes you to tour the Victorian elements of his country home and surroundings at the Missouri Botanical Garden. Opened to the public on June 15, 1859, the Missouri Botanical Garden is the oldest botanical garden in continuous operation in the United States. The Garden is an oasis of beauty in the city of St. Louis with 79 acres of horticultural display, as well as a center for botanical research and science education. Visit www.mobot.org!

- 45 seconds#10 – Welcome from Henry ShawStop on Spoehrer Plaza

Hello, and welcome to the Missouri Botanical Garden. My name is Henry Shaw, and this Garden was my gift to the city of St. Louis over 150 years ago, in fact the locals still refer to it as Shaw’s Garden. Since 1859, millions of visitors have delighted in the finest of horticultural displays. Not only is my Garden a place of beauty, it is also a leading center for scientific research about plants. Today, it is widely considered one of the top three botanical gardens in the world.

Please join me for a journey through our history. Follow the prompts on signage throughout the grounds to learn more about my beloved Missouri Botanical Garden.24 March 2009, 4:42 pm - 1 minute 17 seconds#11 – How old is this greenhouse?Stop at Linnean House busts / Photo of original landscape

Although Henry Shaw owned expansive property, he planned the Missouri Botanical Garden for a relatively narrow strip of land stretching north from his country home. A fruticetum, or collection of shrubs, grew in what is the present-day parking lot. Just south of this area was the Main Conservatory, built in 1868 to house exotic plants. Shaw completed this small brick greenhouse in 1882. He wanted it to complement the original main conservatory pictured on the sign. He named it the Linnean House to honor Carl Linnaeus, the botanist who created our standard scientific system of naming plants and animals.

The Linnean House originally housed palms, citrus trees, and other plants that could not withstand St. Louis winters. The original plants were all in pots; there were no permanent plantings. After World War I, the house was renovated: the roof was converted to all glass, and many loads of soil were brought in to create landscape beds. Rare conifers, rhododendrons, azaleas and heaths were planted, along with a handful of camellias. A central water feature was added and fashioned to look like a natural spring along the Meramec River. In the late 1930s, the conservatory was converted to house mainly camellias, which still grow here year-round. The Linnean House remains the oldest continually operating greenhouse west of the Mississippi River.24 March 2009, 4:42 pm - 1 minute 29 seconds#12 – How did Henry Shaw use this building?Stop at Spink Pavilion / Photo old entrance gate

From the start, founder Henry Shaw had planned for his garden to be a place of public enjoyment. In March of 1859, the Missouri legislature passed the official charter, and on June 15, 1859, the Missouri Botanical Garden opened its doors to the public.

Shaw welcomed visitors in grand fashion, they entered his Garden through the pillars of an impressive stone structure, in fact it was this building – well – more or less!

Originally the Main Gate aligned with Flora Avenue, which at that time was a small tree-lined path leading to the Garden from the edge of the city at Grand Ave. Over the years, Flora expanded and the street was no longer in alignment with the entrance. By 1920 the original entrance was torn down and the materials reused to build this larger entrance structure, which is once again in alignment with Flora Ave.

Today, this building is known as the Spink Pavilion and represents a fun bit of Garden Trivia. On the exterior of the building, is inscribed “Missouri Botanical Garden, 1858.” It remains a mystery as to why the actual 1859 opening year was not used. No matter the cause of the delayed opening; the earlier date is a permanent reminder of Mr. Shaw’s optimistic nature.

In 1982, the Garden built a new visitor center entrance at 4344 Shaw Boulevard and the original Main Gate was closed and repurposed as a private event space.24 March 2009, 4:42 pm - 1 minute 5 seconds#13 – Why did Henry Shaw name the house Tower Grove?Stop at Sassafras grove / photo original look of TGH

The land that is known today as the Missouri Botanical Garden was discovered by Shaw as he explored the territory surrounding the city of St. Louis. It was a wide and seemingly endless expanse of tall-grass prairie, with few trees, except for a small grove of sassafras growing on a low hill. Shaw purchased the land and determined to establish a country home on the property.

Shaw retired at the young age of 39. Years later prior to his last trip abroad he hired prominent local architect George I. Barnett to design his country home, a two-story Italian-style villa of painted brick. Completed in 1851, the house featured an asymmetrical design, with two high-ceilinged stories on Shaw’s western half, three low-ceilinged stories on the servants’ eastern half, and a tall tower in the center. Approaching from afar, the home’s tall tower and the sassafras grove were the first objects visible. For this reason Shaw gave the name, Tower Grove, to his country estate.24 March 2009, 4:42 pm - 1 minute 25 seconds#14 – What was this building used for?Stop at Museum Building

In 1856, as Henry Shaw embarked on the creation of his garden, he sought the guidance of Sir William Jackson Hooker, the director of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. Shaw wrote to Hooker about his property, about the extremes of the American climate, and to ask for help. Hooker responded, urging Shaw to combine both beauty and science into his future garden. He recommended Shaw acquaint himself with Dr. George Engelmann, a St. Louis physician and botanist.

Dr. Engelmann was familiar with Henry Shaw before they ever corresponded. Engelmann had already written to premier botanist Dr. Asa Gray of Harvard, describing Shaw’s project and expressing his desire that something “valuable and permanent” would come of his efforts.

Undoubtedly, Shaw’s associations with Sir William Hooker, Dr. Gray, and Dr. Engelmann helped shape the Garden’s future as a noted center for scientific endeavors. To augment this role, Shaw generously endowed the Henry Shaw School of Botany and the Engelmann Professor of Botany at Washington University in 1885. In his will the Garden’s future as a scientific institution was secured.

In 1859, Shaw commissioned architect George I. Barnett to design this Museum Building to house the Garden’s original library and herbarium. It was completed the following year. Today the Museum Building is closed to the public.24 March 2009, 4:42 pm - 1 minute 18 seconds#15 – Who is this woman?Stop at Temple of Victory

In typical Victorian fashion, Missouri Botanical Garden founder Henry Shaw arranged for his mausoleum long before his death. In 1862 he constructed a mausoleum out of Missouri limestone and placed the structure in a grove of trees directly in front of Tower Grove House. However, in 1885, Shaw changed his mind believing that the limestone would not hold up to the elements over time. He had the limestone structure moved here, and commissioned a marble statue, The Victory of Science over Ignorance, to be placed inside in 1887.

The statue is an exact copy of the statue by Vincenzo Consani in the Pitti Gallery at Florence, Italy. In this statue Victory is depicted with her sword laid aside and writing on a shield with an inscription below that reads: The Victory of Science over ignorance. Ignorance is the curse of God. Knowledge is the wing wherewith. We fly to heaven.

Shaw believed that, in addition to providing recreational, educational, and aesthetic benefits, botanical gardens should expand and apply knowledge about the natural world. For 150 years, the Garden has maintained Shaw’s emphasis on research and conservation. Today, the Missouri Botanical Garden is one of the world’s leading scientific institutions studying plants and working to preserve biodiversity around the world.24 March 2009, 4:42 pm - 55 seconds#16 – Who lies here?Stop at Mausoleum / photo posing for sarcophagus

Shaw commissioned George I. Barnett for this octagonal mausoleum made of granite, complete with a domed copper roof and cross on top. The stained glass is of particular note, being of exceptional quality. The tomb is inscribed with words from the scripture:

How manifold are Thy works; in wisdom Thou hast made them all; the earth is full of Thy riches.

Before his death, Shaw posed for the marble statue that is inside the tomb. Sculptor Ferdinand von Miller II, developed sketches from the photographs and created a clay model for Shaw to approve. The sculpture shows Shaw at rest, holding his favorite flower: a rose.

Henry Shaw died of malaria on August 25, 1889 at the age of 89. In keeping with his will, he was the first and the last person ever to be buried at the Missouri Botanical Garden.24 March 2009, 4:42 pm - 2 minutes 7 seconds#17 – Who am I?Stop at Henry’s statue in front of Tower Grove House / Photo of younger Shaw

Well, hello again! This is a statue of me, Henry Shaw. I was born on July 24, 1800 in Sheffield, England. I received my education in Sheffield, and then at the Mill Hill School near London. My father Joseph’s iron business had fallen upon hard times and the family could no longer afford my education. Eventually, I was forced to return home and join my father’s business ventures.

In looking for new markets, my father turned to the Americas. In 1818, I accompanied him on our first trip across the Atlantic Ocean to Quebec, Canada. I must have impressed him, because the following year, he sent me to New Orleans – alone at age 18 – to recover a lost shipment. I was successful, but could not find a buyer for the goods. Determined to find a market, I purchased a passage up the Mississippi River on a steamship, the Maid of Orleans. The 40 day trip cost me $120. On May 3, 1819, I landed in a small French town called St. Louis. I spent 20 years here, selling hardware, cutlery and other metal products to the settlers headed westward. Business was very good. I made more than $22,000 in 1839 alone, “more money than any man in my circumstances ought to make in a single year.”

I retired at 39 with nearly $250,000 and focused my attention, skills and resources on real estate. I bought and rented many city and rural properties. Throughout the 1840s I traveled extensively around Europe and parts of North Africa and the Middle East. Inspired by my travels, I returned to St. Louis and began building this Garden around my country estate.

You can learn more about my travels by reading my Travels with Henry blog at www.mobot.org.24 March 2009, 4:42 pm - 1 minute 26 seconds#18 –What was “The Grand Tour” that Henry Shaw took during his lifetime?Stop at Victorian Garden / photo of the parterre

Sheffield-native Henry Shaw called St. Louis home, but throughout his life he remained a proper Englishman at heart. In the 19th century, no English gentleman’s education was considered complete until he had made “The Grand Tour,” an extended trip intended to expose one to the arts, languages and cultures of Europe’s great civilizations. Upon his retirement, Shaw set out on such a trip, leaving his business interests in St. Louis to the care of his younger sister, Caroline. Throughout the 1840s, Mr. Shaw made several extended trips abroad, staying in Europe for as long as three years at a time.

In 1851, on his final venture, he set out for London and the first World’s Fair. He visited the fair’s Crystal Palace Exhibition and the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, as well as the beautiful gardens at Chatsworth in Derbyshire, among the finest in the world. Shaw was inspired. During a walk through the Chatsworth gardens, he conceived the idea to create a garden of his own in St. Louis, his adopted home. Henry Shaw dedicated the rest of his life to the development of the Garden for study and preservation of plant knowledge and enjoyment of the people of St. Louis.

This garden recalls the style and feel of the original formal garden, called a parterre, that was located where the reflecting pools in front of the Climatron are today.24 March 2009, 4:42 pm - 1 minute 11 seconds#19 – Did Henry Shaw live here?Stop at Administration Building / photo of residence downtown

Garden founder Henry Shaw’s Town House was originally located on the southwest corner of Seventh and Locust streets in downtown St. Louis. Built in 1849, the three-story, traditional residence contained seventeen rooms and two kitchens. It was designed by architect George I. Barnett, who also designed Shaw’s country estate, Tower Grove House.

Henry Shaw passed away in 1889. In his will, he left $10,000 with instructions for his city home to be moved to this location:

I devise and bequeath my property…to said Botanical garden, including my present City residence…being built of good and durable materials, but unsuitable to its present locality; it is my desire that when deemed advisable by the Trustees of said Missouri Botanical Garden to have the said residence carefully taken down and rebuilt on Tower Grove Avenue in some convenient situation in contiguity to said Botanical garden.

Over the years, the Town House was expanded and used as a scientific research facility. Today it houses administration offices and is closed to the public.24 March 2009, 4:42 pm - 1 minute 11 seconds#20 – Was Henry Shaw married?Stop inside Tower Grove House, piano

Shortly before the Missouri Botanical Garden opened, founder Henry Shaw had to deal with a very personal, yet very public matter.

Shaw never married, despite the attempts of several acquaintances to find him a suitable mate. However, he maintained friendly correspondences with several ladies over the course of his lifetime, most notably a young woman named Effie Carstang.

Shaw loaned money to Carstang twice. He also rented a piano to her for one dollar a month, with the agreement that it would eventually be returned. Instead, in July 1858, Carstang sued Shaw for breach of the promise of marriage, seeking a staggering $100,000 in damages.

Shaw denied the claim, but after a stirring and nationally-publicized trial, Effie Carstang won unanimously. The New York Illustrated News called the verdict “the largest sum ever awarded in this country in such an action.” However, the court agreed to an appeal, and eventually reversed the earlier decision. Shaw had spent more than $15,000 in court costs, but kept his $100,000 fortune. He refocused his attention once again on the Missouri Botanical Garden, which had officially opened its doors to the public by the end of the trial.24 March 2009, 4:42 pm - More Episodes? Get the App

- http://www.mobot.org

- en-us

Your feedback is valuable to us. Should you encounter any bugs, glitches, lack of functionality or other problems, please email us on [email protected] or join Moon.FM Telegram Group where you can talk directly to the dev team who are happy to answer any queries.