Podcast – Sati Saraniya Hermitage

Sati Saraniya Hermitage

Dhamma Talks by Ayya Medhanandi and Others at Sati Saraniya Hermitage in Perth, Ontario, Canada

- 14 minutes 16 secondsTaming of the Shrewd

https://files.satisaraniya.ca/audio/talks/2024/Ayya_Medhanandi_Taming_of_the_Shrewd_2024.mp3Download Audio File

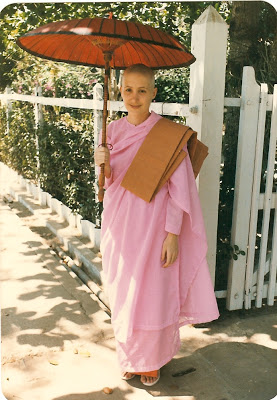

My personal identity was dismantled on the full moon of March, 1988. That was the day I donned the robes of a Buddhist alms-mendicant nun. I’d been practising intensive meditation at the Mahasi Sasana Yeiktha in Yangon, Myanmar (formerly Rangoon, Burma) under the guidance of the most Venerable Sayadaw U Pandita.

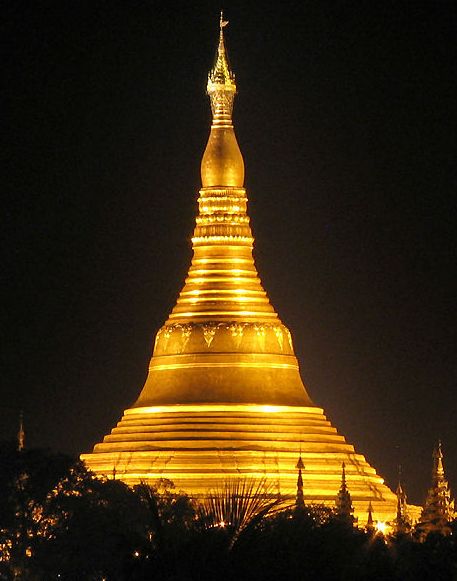

One day, I took leave to visit the holiest stupa in the country, the Shwedagon Pagoda. Precious relics of the Buddha are enshrined in its golden spire which towers 99 metres over dozens of surrounding temples and shrines where you can meditate and perform pujas. I came as a pilgrim, eager to pay homage and make dedications to support my burning wish for ordination as a Buddhist nun.

Traditionally, such rituals are performed at the temple for the day of the week you were born. I soon found the Thursday shrine, for my day of birth; and there I made my offerings – lighting candles and incense, and chanting praises to invoke blessings of all the Buddhas of the ages for my earnest spiritual intentions.

When I returned to the monastery, I approached Sayadaw and made my request. He mentioned one condition under which he would accept me as a candidate – lifetime vows or nothing. I was in my mid-thirties so it seemed inconceivable to swear away my whole life to this practice. Sayadaw noted my hesitation.

“Go think about it”, he advised with great compassion.

Three weeks later, while in walking meditation near his reception room, I could hear him teaching Dhamma to a group of Burmese laywomen. I quietly went in and sat at the back of the room to listen. Suddenly, I realized that Sayadaw would ask me if I had decided. I still didn’t know. So I tried to leave discretely hoping that he would not notice.

But he did notice. After dismissing the group, he invited me to approach the shrine. I bowed and sat respectfully in silence.

“Did you decide?” he asked.

“No, Sayadaw”.

Then, he spoke as if a sword of wisdom was raised above my head: “Will you do it?”

My response was life-changing. “Yes, Sayadaw.”He checked to see if I could be ready in three days and called the monastery nuns to come and take my measurements. My robes were quickly sewn and on the appointed day, the nuns gathered around me to chant blessings while one of their elders scraped away the last remnants of my hair with a cutthroat razor.

Appearing before Sayadaw U Pandita in my freshly tailored pink robes, I felt a radiant happiness as I bowed – ready to complete the ten precept ceremony. After leading me in the recitation of the refuge chants and precepts, Sayadaw would bestow my new Pali name which he selected

according to an ancient formula.

according to an ancient formula.It would begin with a letter that corresponded to the day of my birth. And Sayadaw, knowing my strengths, weaknesses and potential, would choose a fitting name to reflect a quality of mind worthy of aspiration.

Sitting tensely on the teak floor that full moon day, the whirring fan blades punctuated my anticipation. But when I heard my new name, I unexpectedly blenched. Sayadaw looked surprised to see the slightly pained expression on my face.

“What’s the matter, you don’t like your name?” he cajoled.

It was a gentle but potent chastening. I knew instantly that this was not a time to negotiate any aspect of my monastic commitment, but to simply let go and humbly receive whatever was being given. With palms folded together, I conveyed my profound gratitude for this very good name.

Of course, Sayadaw was not to be fooled. He had clearly read my heart. It was true – that name did not resonate with me. But I quietly supplanted such thoughts to accept it as graciously as I could – and not tarnish the auspiciousness of the moment in the slightest way.

The next evening, at the end of Sayadaw’s Dhamma talk to our group of foreign yogis, he motioned me to wait while the others filed out. I approached Sayadaw’s dais, still awkward in my new robes and anxious that he had singled me out. Perhaps he would admonish me about my way of sitting or how I wore the robes.

I bowed. “Yes, Sayadaw?”

“I want to change your name,” he announced.I was stunned and curious. This was to be an added blessing for me – I liked both the sound and the meaning of this new name – Medhānandī. It meant, he explained, the ‘bliss of sharp wisdom’. This was what I was to live up to.

A year later, I again experienced the impact a name can have on our mental fabrications. When I returned to the West, with Sayadaw’s blessings, I joined a community based on the Thai forest tradition. After ten years of training, monks were addressed as, ‘Ajahn’, the Thai word for ‘teacher’.

Eventually, the nuns were also given this honorific – which was an uplift to our morale. Although only a title, still it signaled the respect due to a teacher, one qualified to lead and train younger monastics. An ‘Ajahn’ receives special consideration, but at the same time, shoulders greater responsibility to run the community and care for its members.

As the ten year mark approached, I worried about falling victim to self-importance and conceit if I were to use such an august title. I had seen a number of monastics succumb to this syndrome, and I was reluctant to risk the dangers of fame, gain and power that such a title might impose.

As it happened, after 10 years, I took an extended sabbatical in New Zealand and I lived there as a solitary nun. Rather than using ‘Ajahn’, I chose ‘Ma’. This was the Burmese way of address for monastic women. It seemed down to earth, personable, respectful, and ‘safe’.

Little did I realize how this choice whetted the blade for my own suffering. While everyone happily addressed me as ‘Ma’, they reserved a special respect for those known as ‘Ajahn’ who, at the time, were all monks. That rankled. Wanting due recognition as one equally capable of transmitting the Dhamma, I felt diminished and so I became a casualty of my own making. Even when I settled on the name ‘Ayya’, the title used for nuns, nothing changed.

All was not lost – for while I viscerally felt the painful tides of this process crashing into my heart, I was able to glean an insight true to the new name Sayadaw had chosen for me. Essentially, I saw that no name, title, degree or pedigree can confer true wisdom, authority or respect; nor do opinion, tradition or entitlement bestow them. As the Buddha wisely instructs us:

“One does not become a noble one by birth. It is by one’s deeds that one attains to nobility.”

The riches of this life derive from being true to my work as a spiritual friend, a spiritual mother and daughter of the Buddha, a devotee and supplicant of the Way. My true name is the pure presence behind every name – the emptiness in which all personal identity dissolves. And where only unconditional love abides.

© Ayyā Medhānandī 2024

10 February 2024, 6:00 am

10 February 2024, 6:00 am - 44 minutes 14 secondsJoy is Hidden in Sorrow

How to transcend the small view of ignorance and delusion? We must cross over these false boundaries and delve into the depths at the heart of our hearts. We discover what truly matters in trying so hard to gain wisdom. It’s a question of right seeing – of actually stepping into the boundless abidings beyond greed, hatefulness and delusion. There we touch depths of our inner sanctum – the noblest attitudes of mind. A Dhamma talk delivered in 1996 at a Death & Dying Retreat. Amaravati Buddhist Monastery, UK.

https://files.satisaraniya.ca/audio/talks/1996/19961109-Ayya_Medhanandi_Bhikkhuni-SatiSaraniya-joy_is_hidden_in_sorrow-54346.mp3Download Audio File22 June 2019, 2:52 am - More Episodes? Get the App