Updates, Interviews and More - J.C. Hutchins

Transmedia storyteller & novelist J.C. Hutchins chats with creatives, and provides updates about his own creative work, in this podcast.

- The miles-deep wonder of The Fellowship of the Ring

I’m presently rereading The Fellowship of the Ring. I mentioned this to my Facebook peeps earlier in the week, mostly because I wanted to slag on the Tom Bombadil section of the story. (In my defense, I feel it's a narrative momentum killer; it just goes on and on, and doesn’t seem to contribute much to the greater story.)

But as I read the book this time—including the Bombadil stuff—I've realized that I've personally never read books set in a fictional world that are as convincingly “real” as Middle-earth.

Most writers (and I’m one of these) usually create fictional settings that stand up to what I call the “3 or 4 Rule” of reader scrutiny. Meaning, the book asserts something unique about its setting that’s notably different from the world as we know it, and then savvily provides answers—either explicitly on-page, or implied—that can satisfactorily survive about three or four levels of “But if that’s true, then what about…?” questioning that readers may have about that unique element.

(I reckon that for most readers, this all happens under the hood; they may not even be aware that they're asking these questions or reading their answers. Generally, once the story survives this sniff test, readers go along for the ride. Smart authors understand this and—when things are really popping—proactively address those questions along the way, often on the sly. Like a magic trick.)

But Tolkien’s world doesn’t satisfy just a few levels of interrogation. It’s got an answer for everything, and it all goes hundreds of miles down. Every-damned-thing has a history (often implied more than outright stated), every culture is authentically different from each other, and the foundations for so many of the big set pieces in the story (such as the fellowship’s trek into Khazad-dûm, which is where I am right now in the book) are exquisitely foreshadowed in plain sight far earlier in the story.

The in-world songs and poetry, as much as I fuss about them, are wonderful examples of this. Lore is everywhere in these books. You can’t help but breathe it in.

When I read Fellowship, I’m not reading a story. I am truly visiting a place … a place so brilliantly invented and presented, I’d swear it as real as my backyard.

13 March 2020, 7:03 pm - Some fun brainstorming about Marion Ravenwood, Indy's better half

Here's a spur-of-the-moment pitch, just for fun: MARION is an animated series and comic book series that document the adventures of Marion Ravenwood in two different times in her life:

As a child, traveling the world with her archeaologist father Abner and her friends (this is the animated series)

And after the events of Raiders of the Lost Ark with some of those same friends—and with the odd cameo by Indy, Sallah, etc. (this is the comic series)

Occasionally, the events of the kids show and the comic book intersect:

Artifacts might become "lost" in the cartoon and resurface decades later in the comic for adult Marion to pursue...

Nascent villainous forces in the cartoon become full-fledged global cults years later in the comic...

Family mysteries hinted at in Marion's childhood are finally unearthed in the comic…

The show and the comic series easily stand on their own, but watchful audience members will see the connective tissue and learn more about Marion's amazing life—which at many times had moments even more awe-inspiring and death-defying than Indiana Jones' adventures—along the way.

11 March 2020, 3:45 pm - Unlearning A Decade of Doubt

What if you realized one day, like a thunderclap, that a major failure you’d experienced a decade ago—one that had broken your heart for nearly every day of those ten years—had never been a failure at all? What if you realized one day that the shame that had haunted you—that had fed off you, that you yourself had fed, and that you’d allowed to define a decade’s worth of self-doubt, inaction and countless missed opportunities—hadn’t needed to be experienced at all?

I recently realized that I'd spent nearly a quarter of my life sifting through smoking ruins that had been created back in 2009. In the decade leading up to that year, I’d written a few books, had dedicated nearly all my free time to podcasting and evangelizing them, and wound up making lifelong, life-changing friends along the way.

What began as a lark evolved into a mission, and eventually became an obsession: publication. I desperately wanted my books to be published. I needed them to be published. I needed that because I needed my talents to be validated in a way that I was emotionally incapable of doing myself. This is never a wise reason to pursue a goal, but I’m not the first person to pin the fate of my self-worth on the approval of others (rather than responsibly forging that love and confidence within myself), so there you go.

If publication had been the sole motive fueling my obsession, perhaps the past decade would’ve unfolded differently. But it wasn’t enough to see the book on a Barnes & Noble shelf. It needed to be a success. It needed to startle the world with its cleverness and become the kind of financial success story that could enable me to write books full-time for a living. That’s the dream of most writers, and it became my obsession.

In the publishing industry, this dream is rarely achieved. I knew that then. It hardly mattered.

2009 came. Two of my novels—both the first books in planned series—were published. I wept in disbelief when I saw them on bookstore shelves. Neither achieved the kind of success needed to greenlight the publication of the sequels, much less enable me to solely write books for a living.

I was heartbroken. Furious. Isolated. Lost. The novels hadn’t failed; I had failed. I was an unmitigated failure.

I have spent the past 10 years standing in the long shadow of that year. I hated myself. If I’d actually been a talented storyteller, I reckoned, things would’ve been different. Hack. Fraud. It was obvious I was a no-talent fraud, and it was obvious I would always be a no-talent fraud. The world saw me for what I was, and was laughing. I had it coming.

I immediately permitted myself to be enslaved by this thinking. I listened to the voice (in great part because I’d heard a variation of this voice for as long as I could remember), and believed what it said, and fed it my fear, my fear of failure, my creative energy, my optimism, my motivation, my goodness. I became ossified, immovable and unwilling to change. Failure. Fraud. You goddamned fool. You broken bulb. You unremarkable thing. You deserved this.

I haven’t invested a consistent effort in writing fiction ever since.

I’ve spent the past few years trying to unlisten to this sly voice in my ear and unwrap its familiar arms from my chest. I’ve made pockets of progress here and there—and have created a handful of beautiful things along the way—and I’m proud of that. But the darkling lover is persuasive. It knows how I think. It knows precisely what to say. It purrs.

It tells me that it is far easier to sit here—right here in the dark, right here where the surroundings are known, though terrible—than to stand up and walk out the door into sunlit uncharted territory. It’s the Devil you know, after all.

But then the thunderclap came last week, as I meditated. My perspective shifted entirely. I had not failed in 2009, I suddenly saw. I had never, ever failed. I had succeeded. I had soared.

It is the dream of practically every writer to craft a story that seizes the imaginations of readers and pulls them into a place where they—if only for a few hours—no longer think about their own lives, or their own seductive anxieties, or their responsibilities. I realized, perhaps for the first time in a thoughtful and contented way, that my books have unequivocally done that very thing.

I realized, perhaps for the first time in a thoughtful and contented way, that my books have been enjoyed by many tens of thousands of people—real actual flesh-and-blood people with families and jobs and friends. True lives, across the globe, impacted in some small way by my words.

I realized, perhaps for the first time in a thoughtful and contented way, that the chances of a novel being published by a major publisher are infinitesimally small … and that the chances of seeing that book in a brick-and-mortar bookstore are smaller still. As I meditated, I cried in disbelief all over again. My books had beaten the odds.

Writers write. They write the very best tale their talents and time will allow. The luckiest ones have the great (greatest?) honor of having their work purchased by a publisher and sent out into the world, for all to see.

What the world does then has little, if anything, to do with the author. The tale is as good as it can be. It finds a home in a great many minds and hearts, or it doesn’t. But its purpose for being—to be excavated from the mind, to become, to be set free—has been achieved in the most glorious of ways. It exists.

I see the world more clearly now, but ache for my missteps. I regret spending most of my life not having the emotional ability to appropriately see my talents for what they are. I regret falling prey to a lifelong all-or-nothing mindset that equated realistic outcomes and learning experiences with outright failure. I regret cozying up to the ravenous, nihilistic snake-self within me that insisted that indecision was always the best-possible decision, and that Staying Right Here was always better than Going Out There.

All of which is a longwinded way of saying that I was born to write books, and to entertain people, and to provide a brief respite from an ever-hostile world, and that’s it. Success isn’t publication. Success isn’t making a full-time wage from writing fiction. Success is found in the doing of the thing, in its becoming, in the process of blossoming into a thing that rightly and truly exists.

Success is the journey, friends.

I am going to write books again.

6 March 2020, 5:21 pm - Thank you, Blanche

I learned one of the most important lessons about writing dialogue and character by watching The Golden Girls.

The lesson: A character should be so clearly realized that when they say something in a scene, the dialogue should map exclusively, and exquisitely, to them. Someone else could deliver the same narrative information, but never in the same unique way this character would.

Case in point, which I remember seeing when I was a youngster: No one but Blanche could've said this.

13 February 2020, 4:04 pm - Will You Play Dotty’s Game?

“You never studied.”

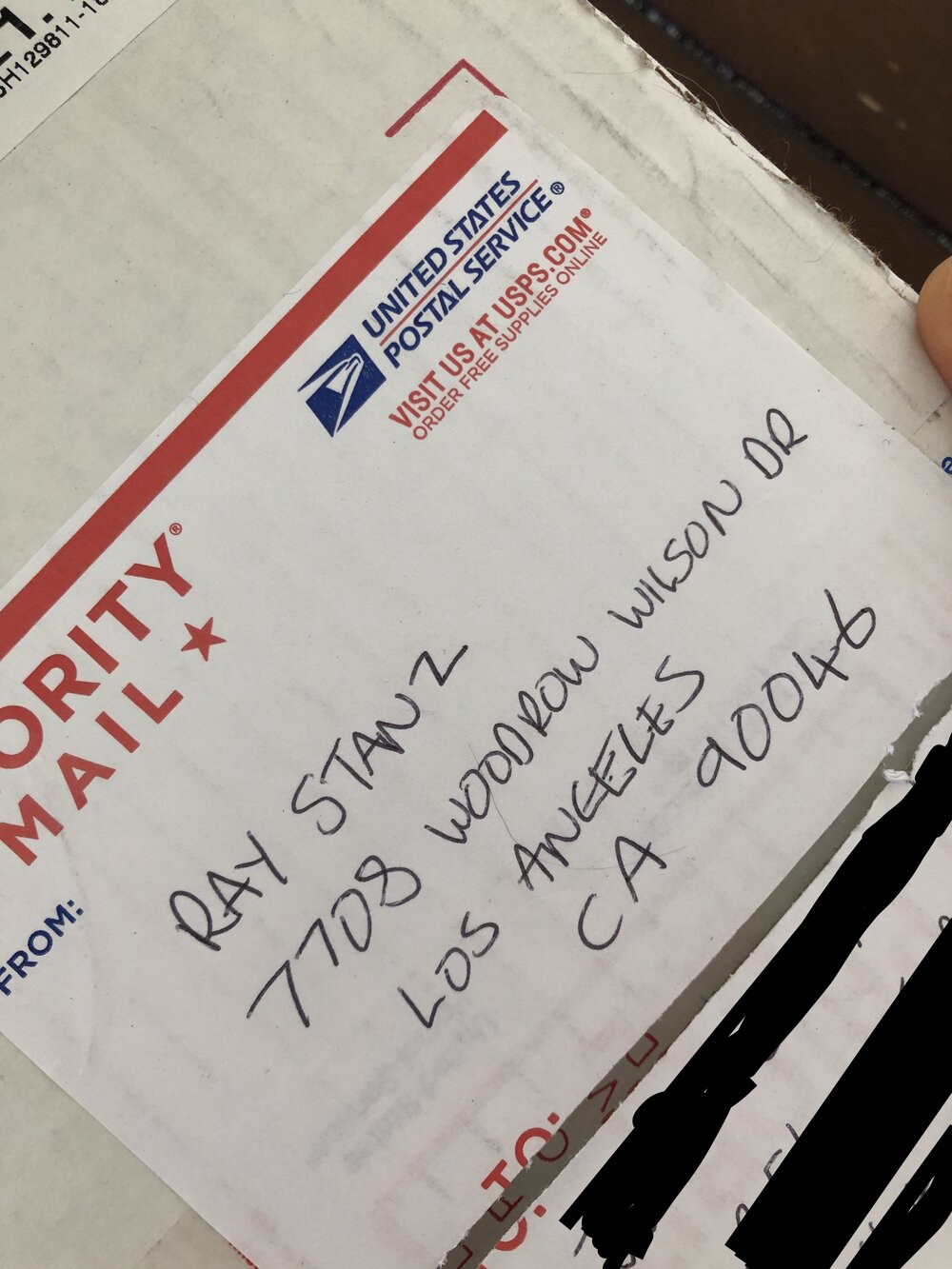

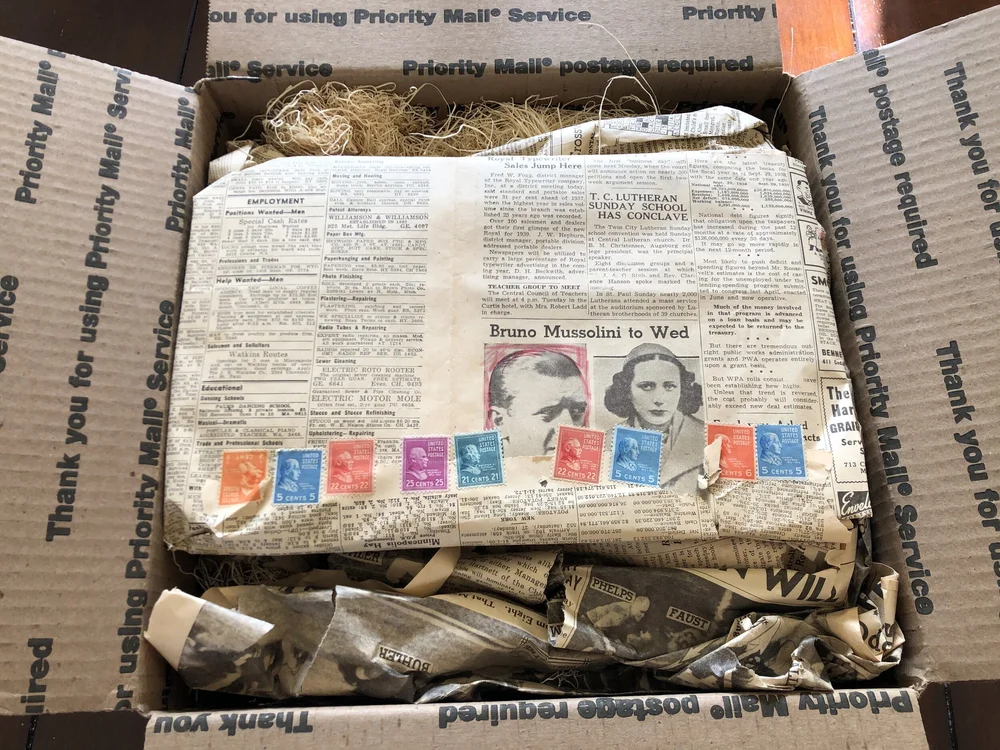

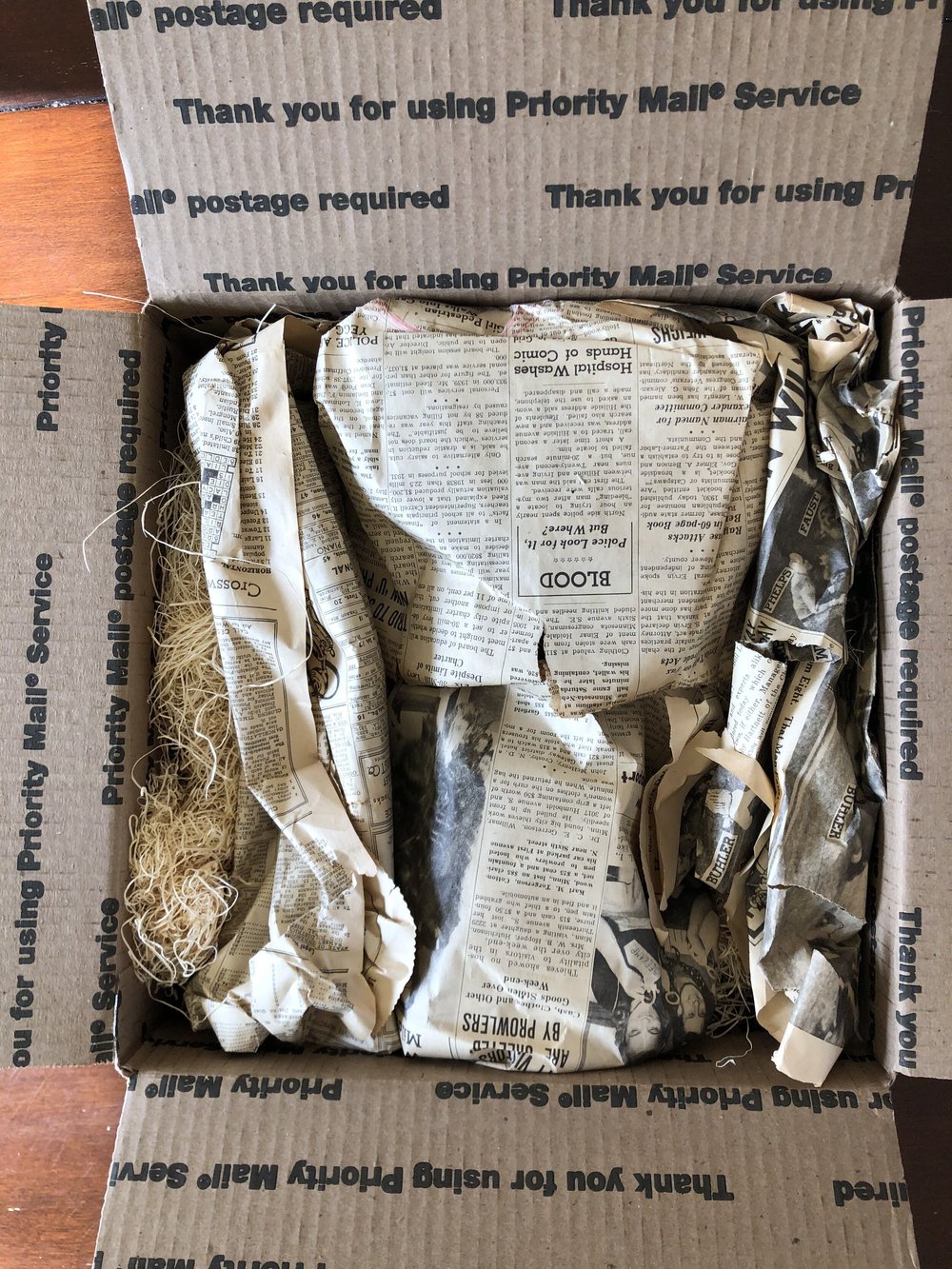

More than a week ago, I received a strange package from Los Angeles.

The return address label declared the box was shipped from “Ray Stanz” (a misspelled nod to a character in Ghostbusters, played by Dan Aykroyd) with a return address of 7708 Woodrow Wilson Drive (which is a former home of Aykroyd, which he claimed was haunted by ghosts).

I immediately suspected that the box was a trailhead for an Alternate Reality Game, and contained goodies that would provide a “rabbit hole” gateway into the game’s narrative. I’ve received several packages like this in the past, and always use the opportunity to document and share my unboxing of the package.

I do this to celebrate the awesome artistry of what’s inside … and also to provide folks on the internet with whatever information, puzzles and other mindbenders that might be required to advance the narrative.

The experience with this box from Los Angeles was very different … and I must admit, downright terrifying. If you want to see the unboxing in real-time (and my horrified reactions throughout), take a peek at the first video below. The second video was shot and edited after I’d composed myself a few days later.

Package From a Stranger, Part 1

Package From a Stranger, Part 2

Photos and More Info About the Package

It’s been 10 days since I opened the package, and I’m no closer to solving the riddles within than I was when I received it.

For a few days, I suspected that the package’s spooky contents weren’t a trailhead for an ARG at all, but instead some kind of morbid joke played by a friend—or something worse, like a legit attempt to terrorize me. This dread eventually passed when, by pure happenstance, I spotted a critical clue in one of the package’s artifacts. This convinced me that the box is indeed an ARG trailhead.

Here’s a closer look at the package and its contents. These photos may help folks solve any puzzles lurking within, and propel this spooky story to its next stage.

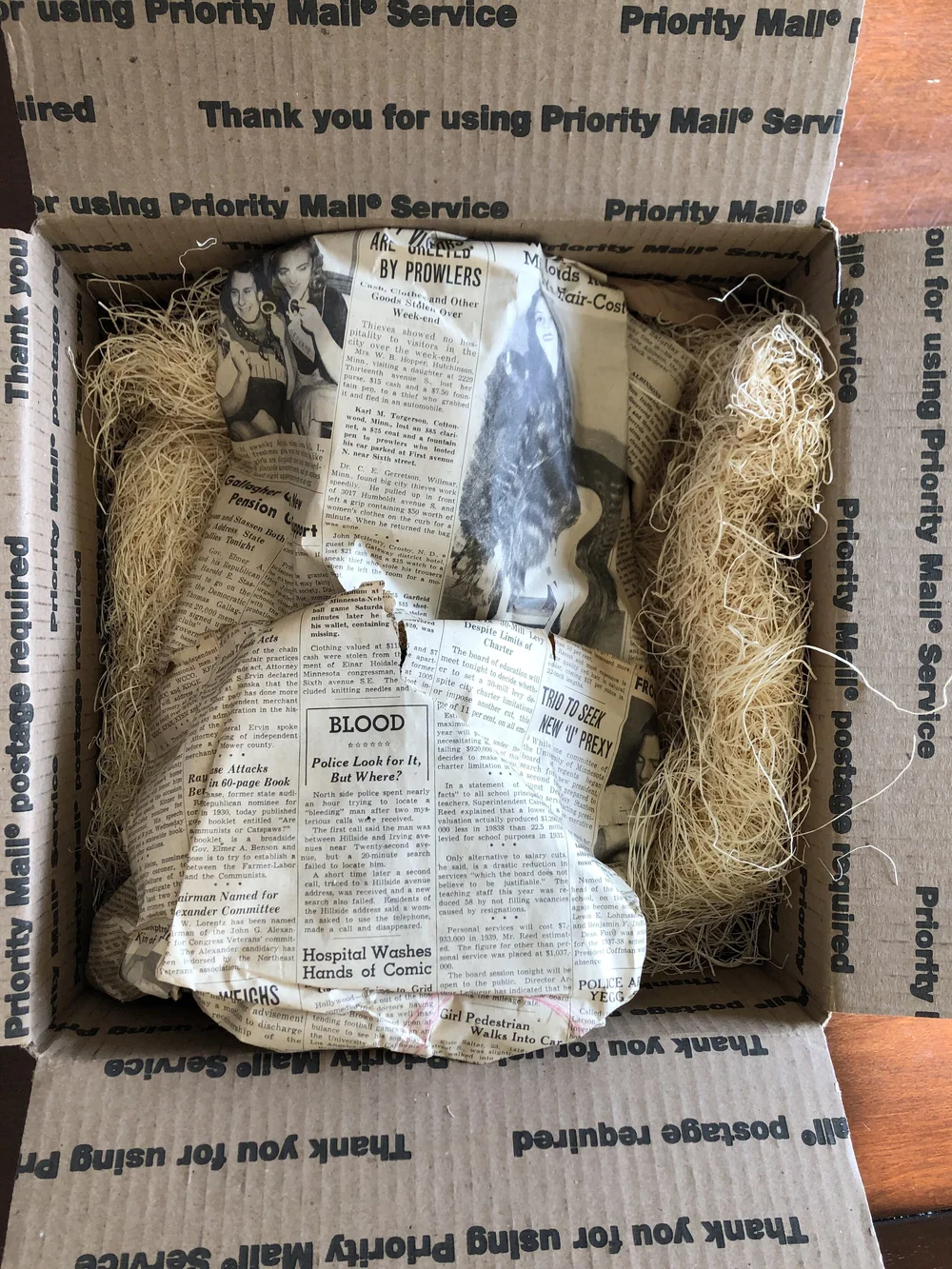

The Package Itself

We know a few things about the sender of the package:

They are one of my Facebook friends

We know this because they viewed a Friends-only post I made on Dec. 4

In that post, I had spotted and shared information about a spooky painted babydoll toy (named “Dotty”) that had been crafted by someone in the Denver area, where I live. Dotty the doll was for sale via a local Facebook Marketplace listing

They know my legal first name and used it on the address label

They know my home address

The list’s last two items don’t distress me much because I know how easy it is to find a person’s name and address online. The list’s first three items are very unusual in that the Facebook post I made about Dotty was published well over a month before I received the package.

Did Dotty herself provide the creative catalyst for the bizarre package I received? Was the ARG project already in the works, and whomever is involved saw my posting about Dotty and leveraged her as a key artifact for the package? I still don’t know.

I confirmed via the box’s USPS tracking code that it was shipped from Los Angeles.

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

The “First Layer” of the Package

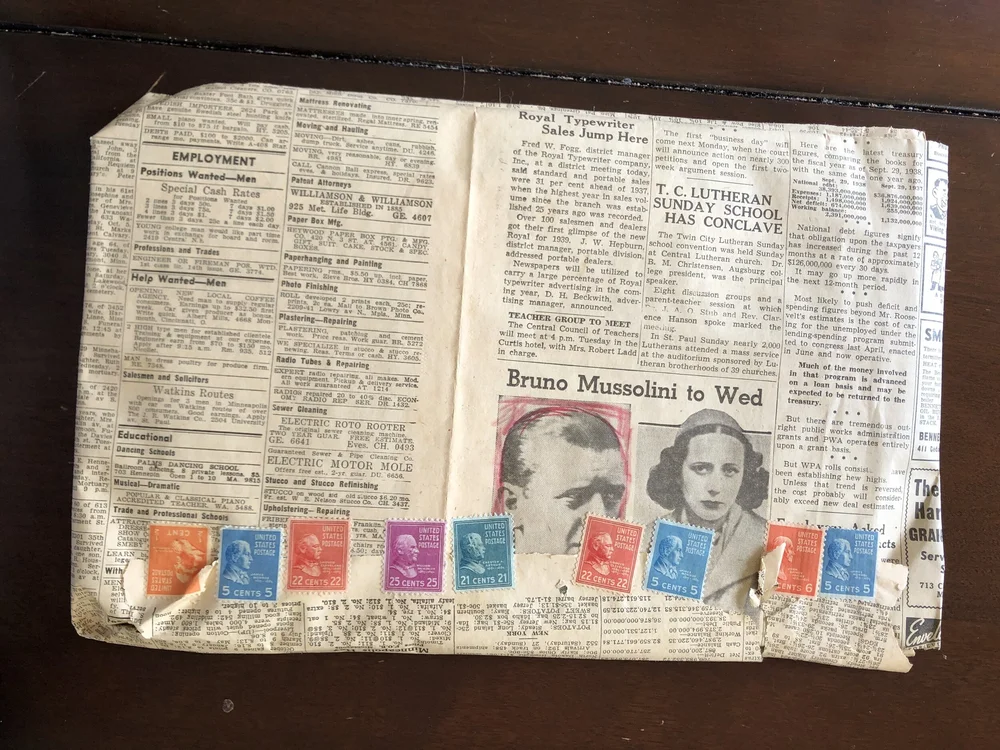

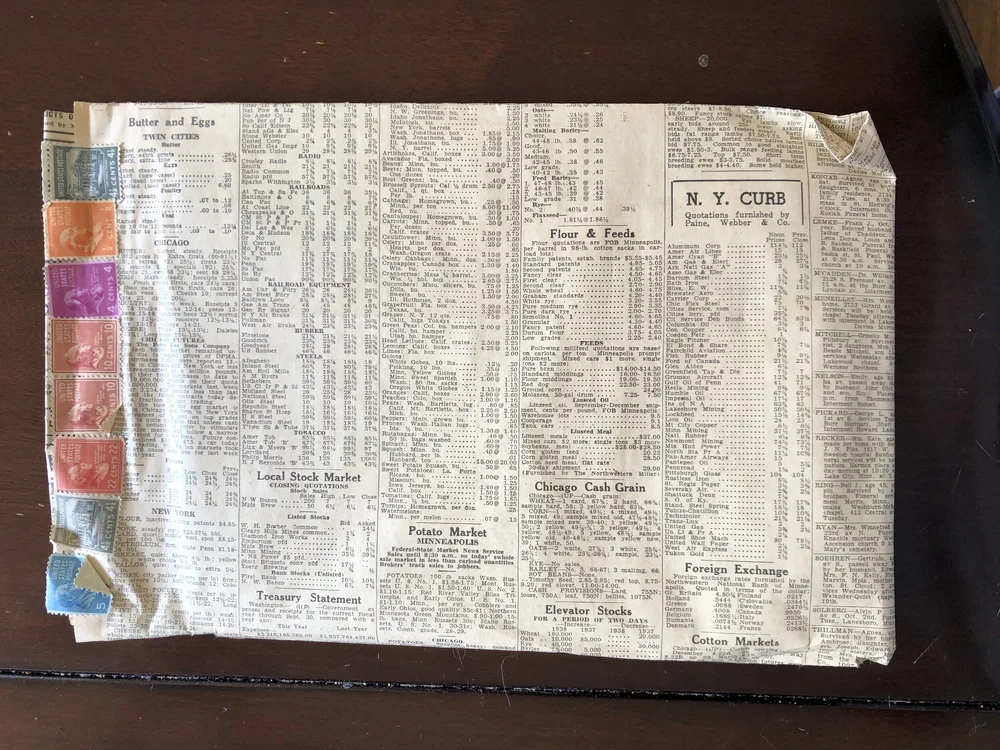

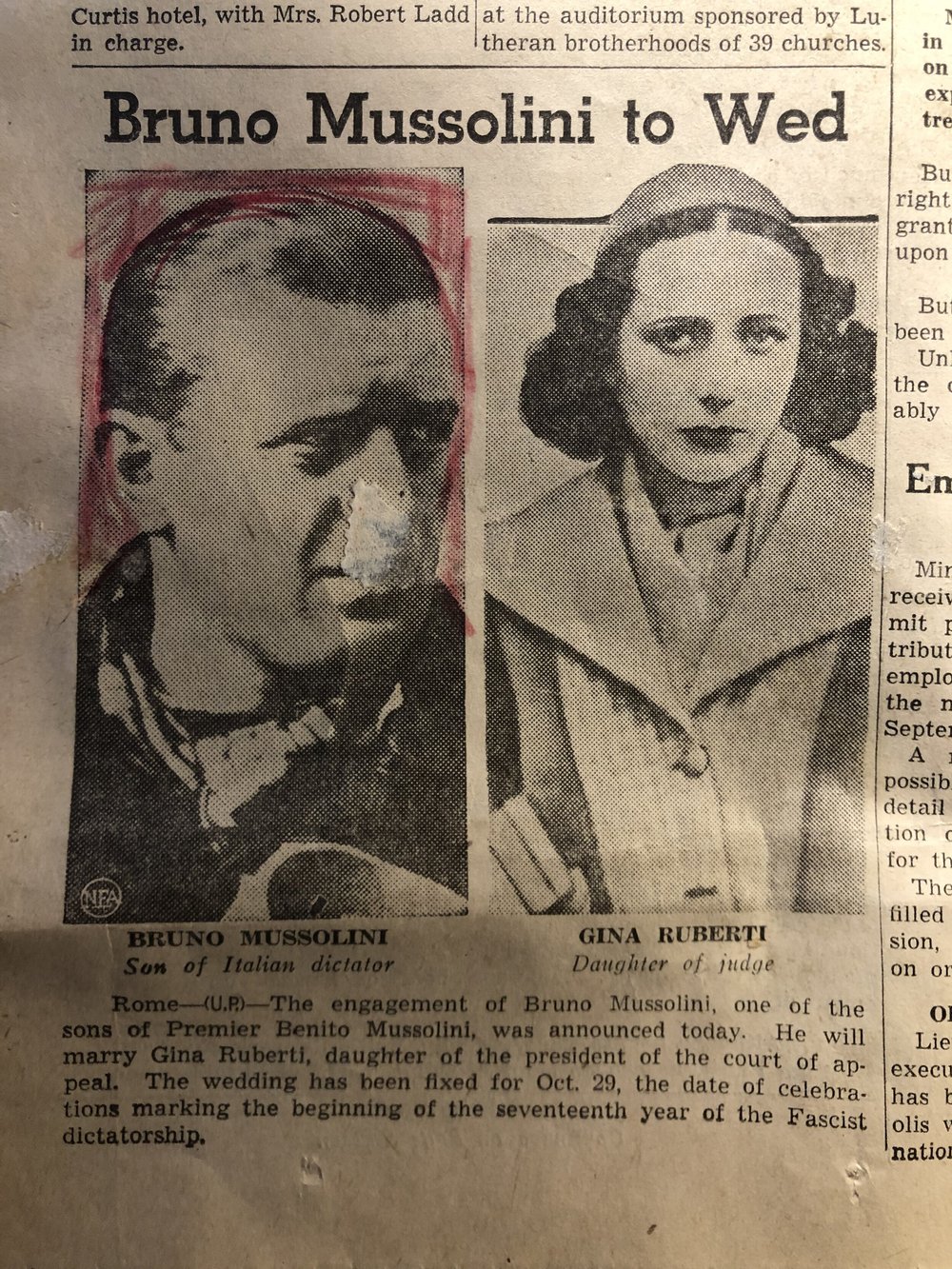

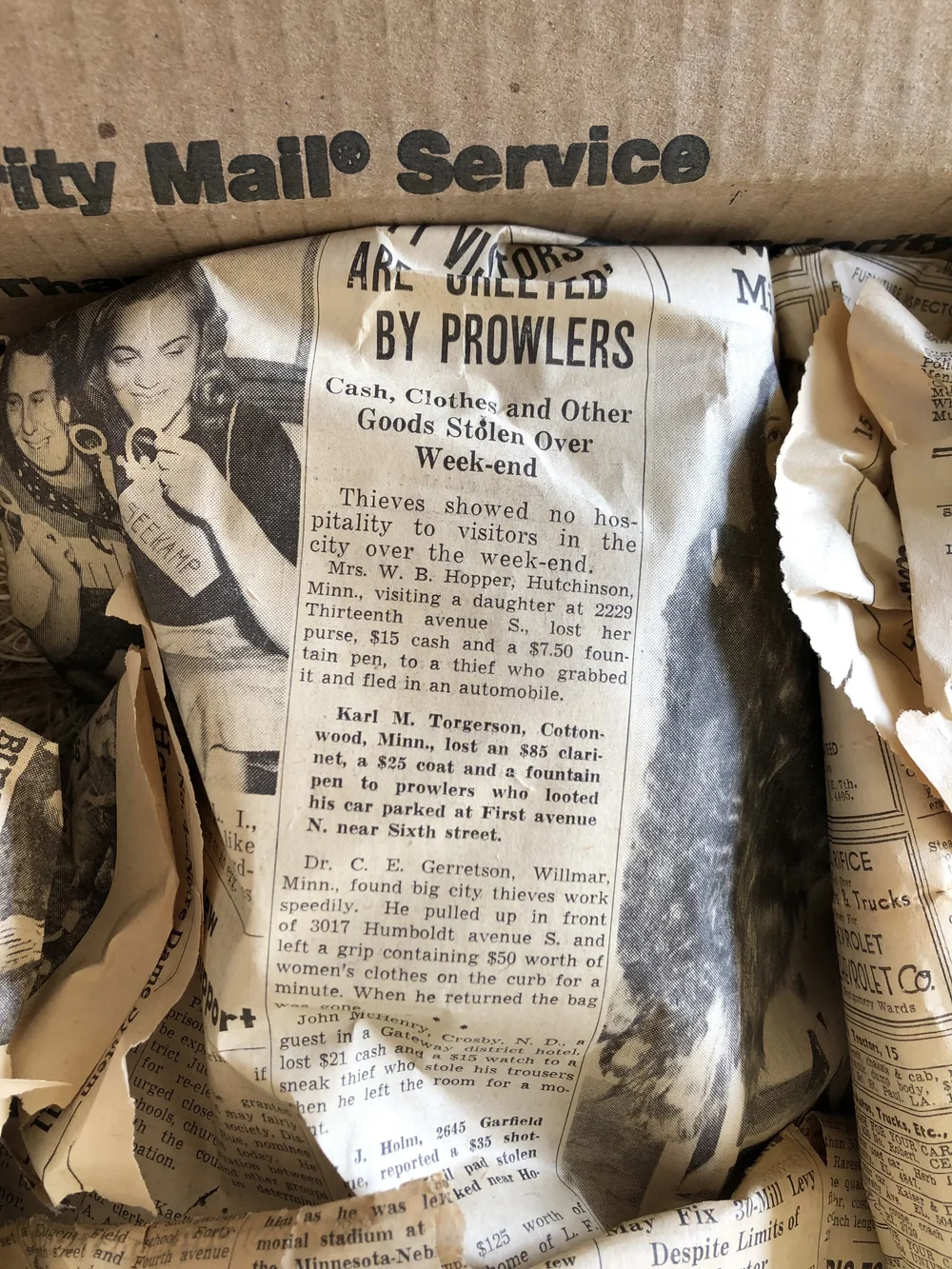

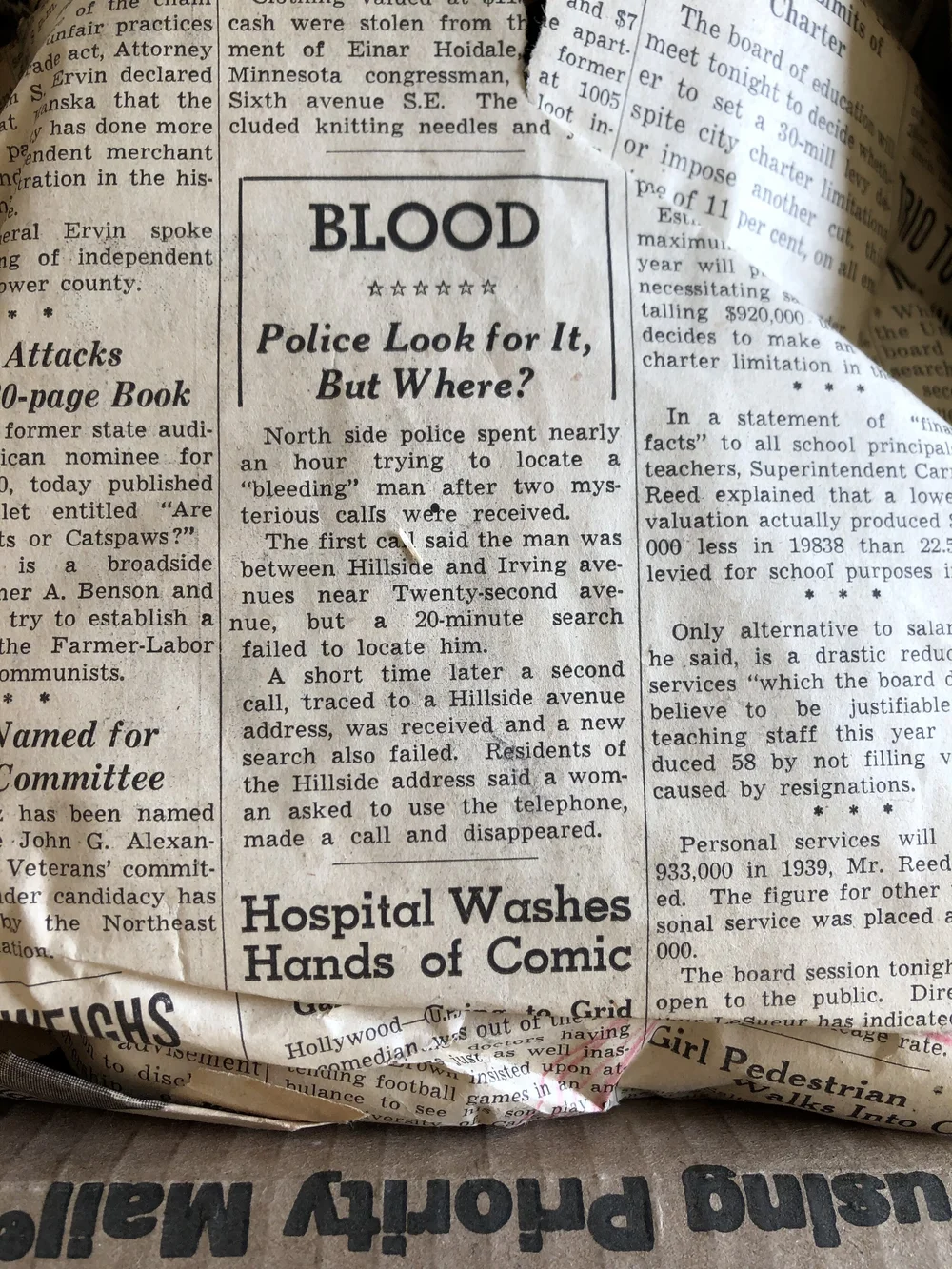

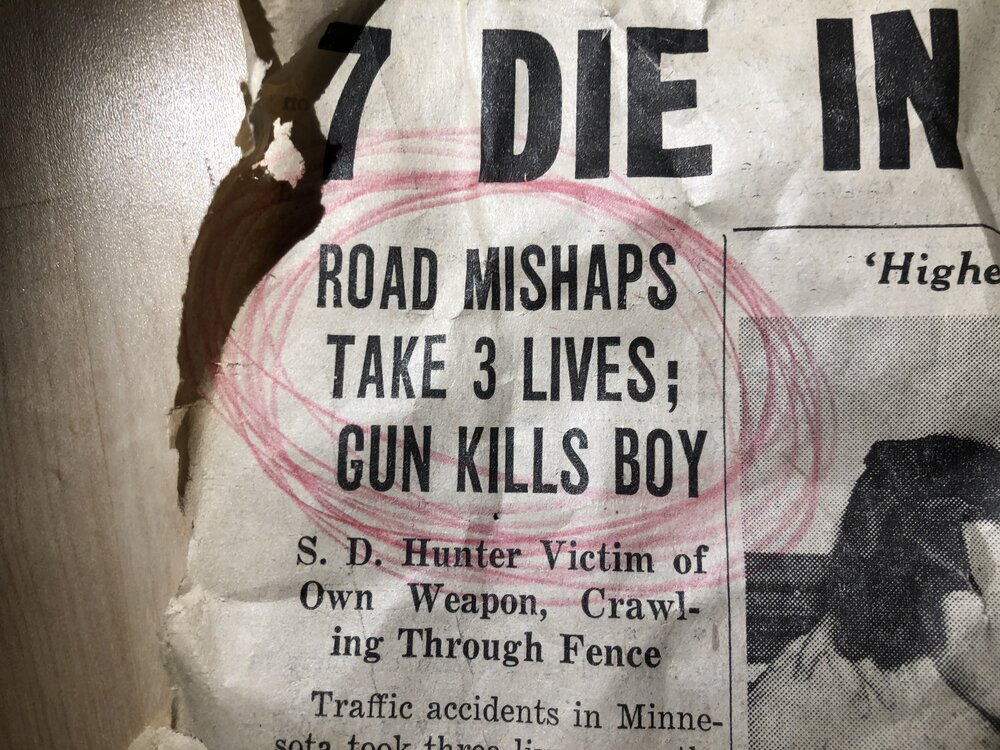

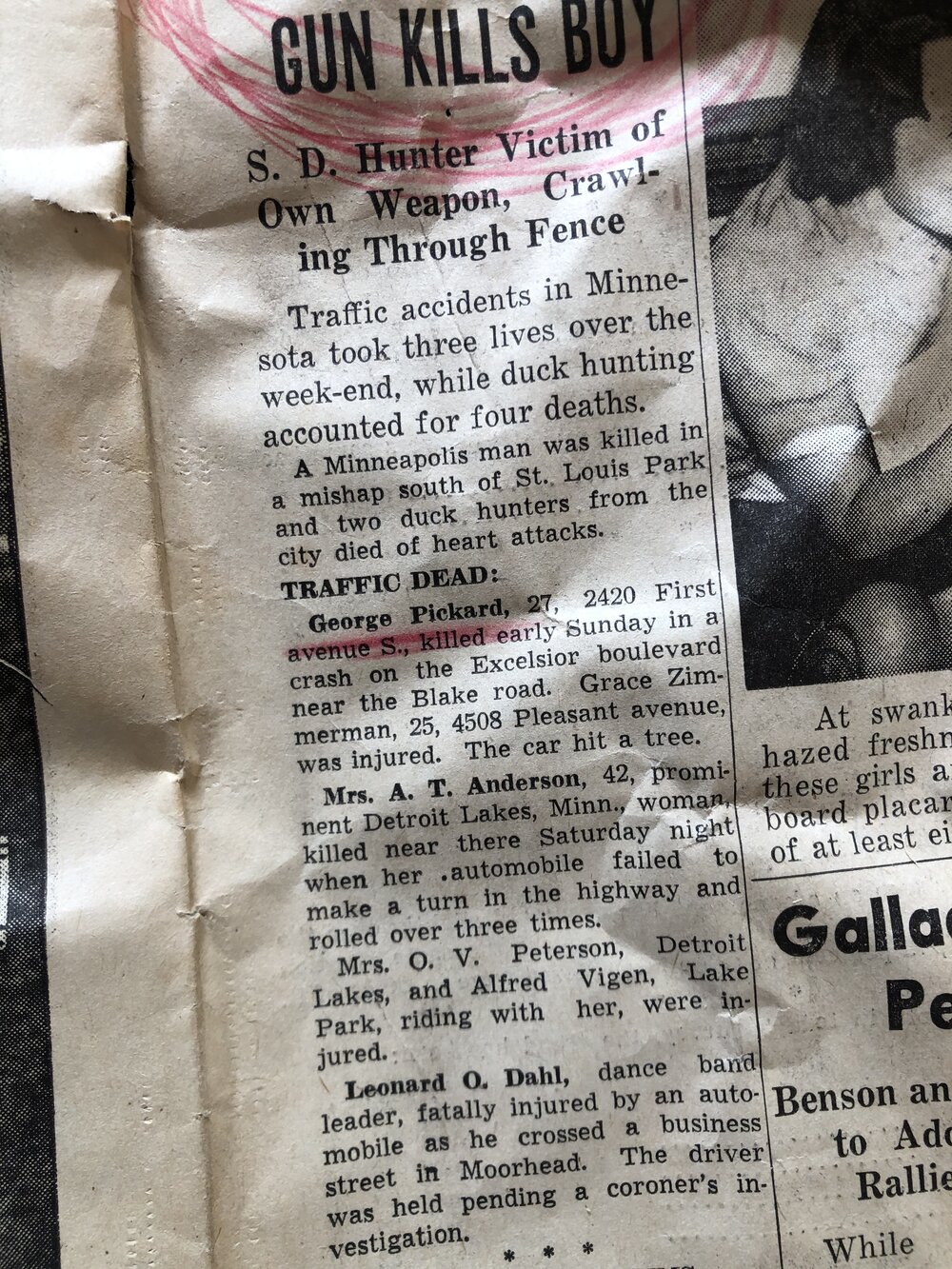

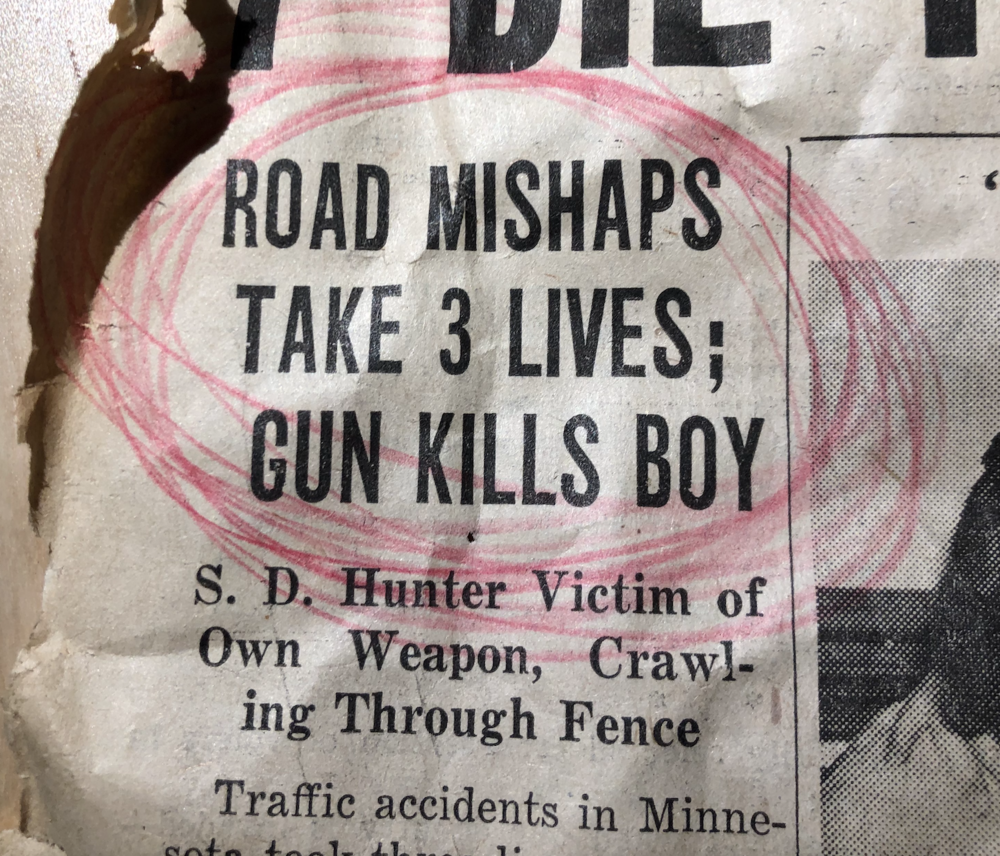

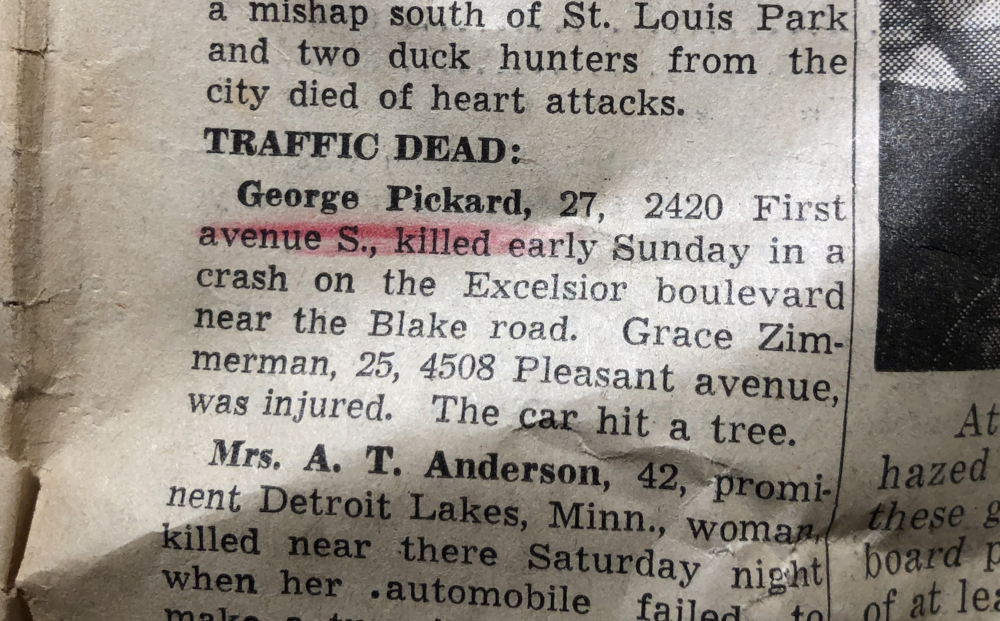

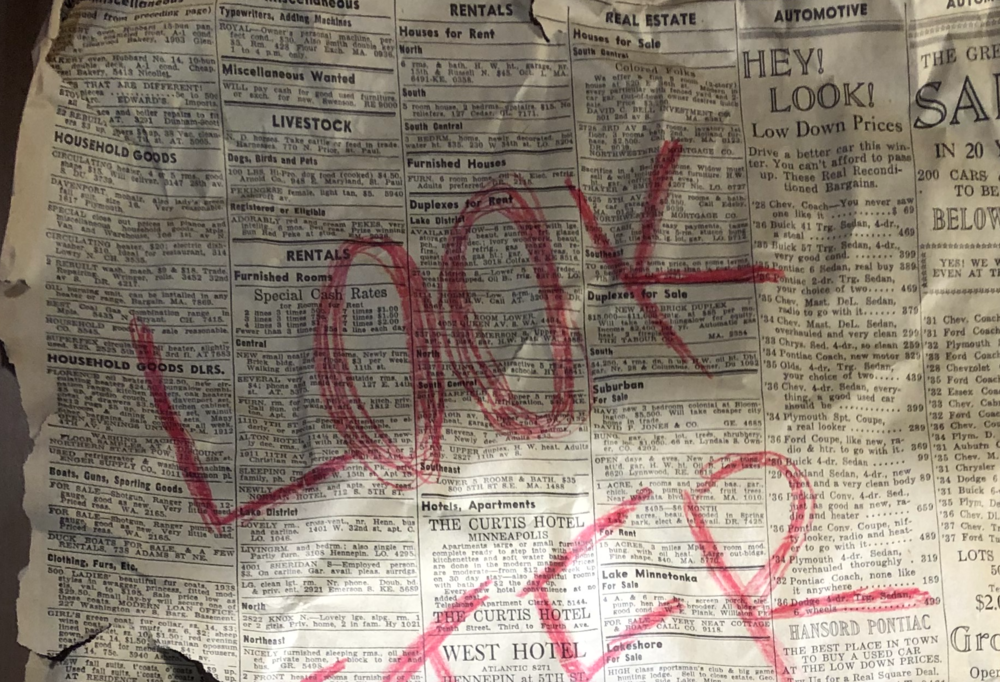

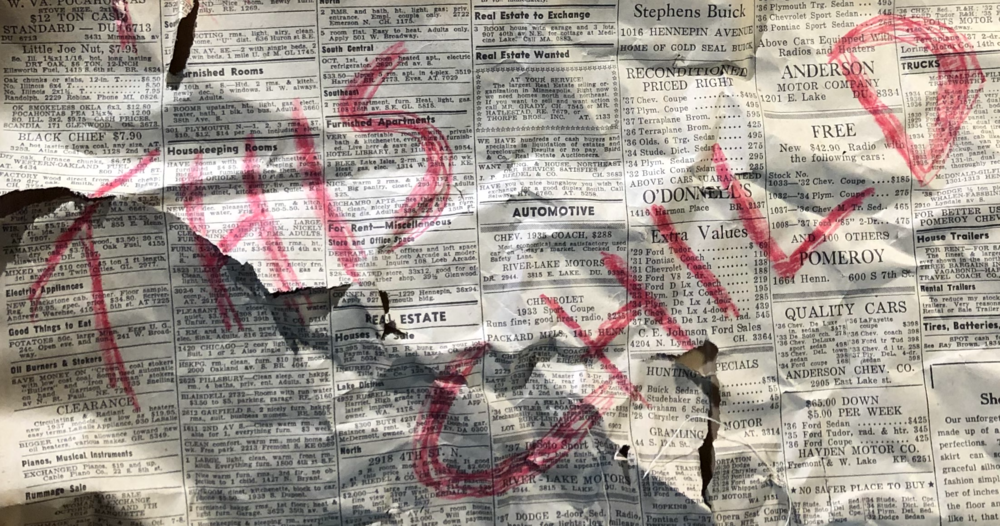

Resting atop a larger item wrapped in newspaper was this strange item, a little smaller than a manilla envelope. Like all the other newspaper wrappings, this featured pages from the Minneapolis Star or the St. Paul Dispatch newspapers, published on Oct. 3, 1938. (The newspaper pages may be clever forgeries, but they certainly feel old, were very brittle, and tore very easily.)

Note the postage stamps used to seal the contents within this smaller package. They were released in 1938, as part of a U.S. President-themed series. Also note that Bruno Mussolini has been highlighted in red pencil.

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

Here are the identities of the presidents seen in the stamps:

Top Side (with B. Mussolini):

Ben Franklin

James Monroe (5th president)

Grover Cleveland (22nd president)

William McKinley (25th president)

Chester Arthur (21st president)

Grover Cleveland (22nd president)

James Monroe (5th president)

John Quincy Adams (6th president)

James Monroe (5th president)

Bottom Side (from bottom to top):

James Monroe (5th president)

White House

Grover Cleveland (22nd president)

John Tyler (10th president)

John Tyler (10th president)

James Madison (4th president)

Ben Franklin

White House

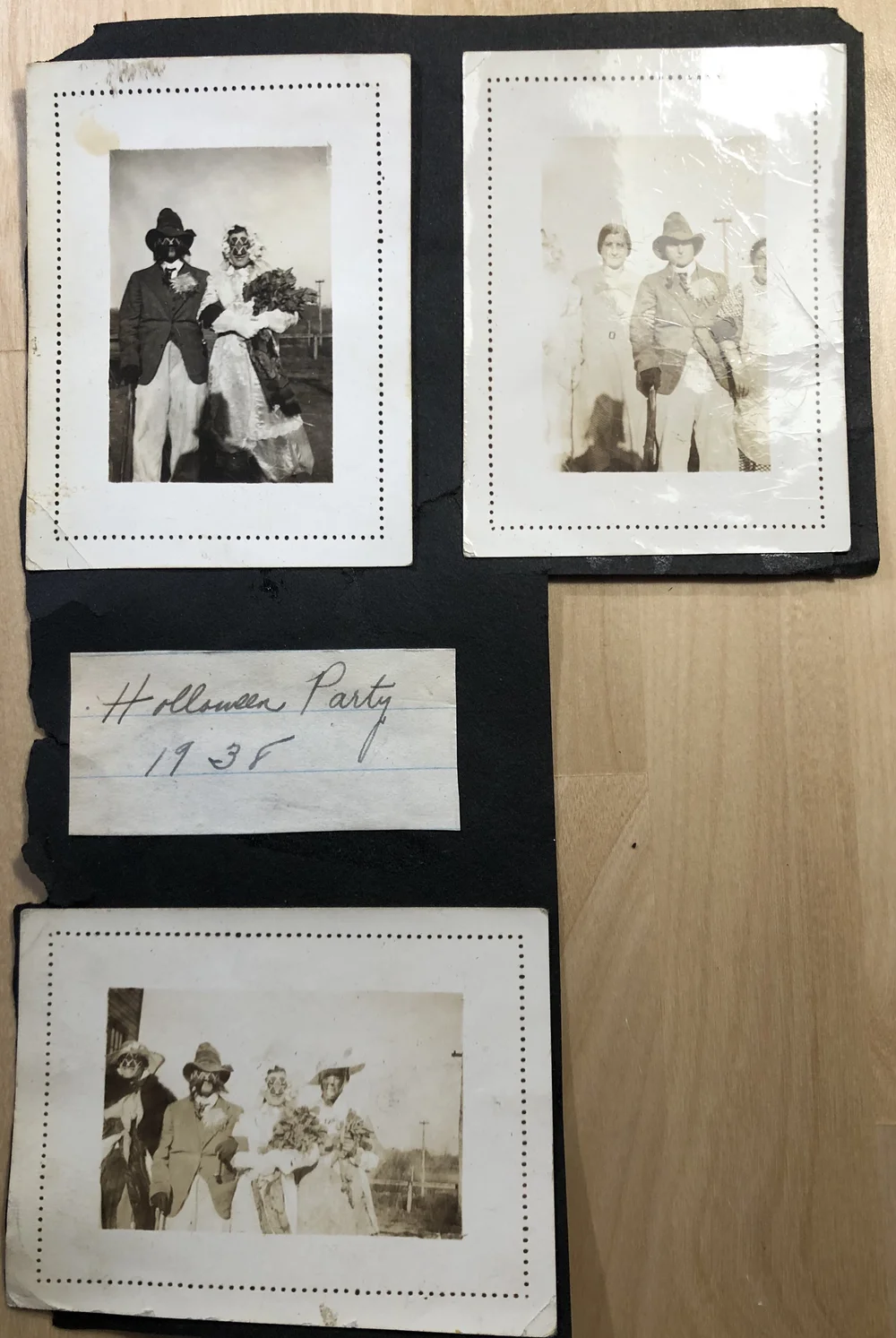

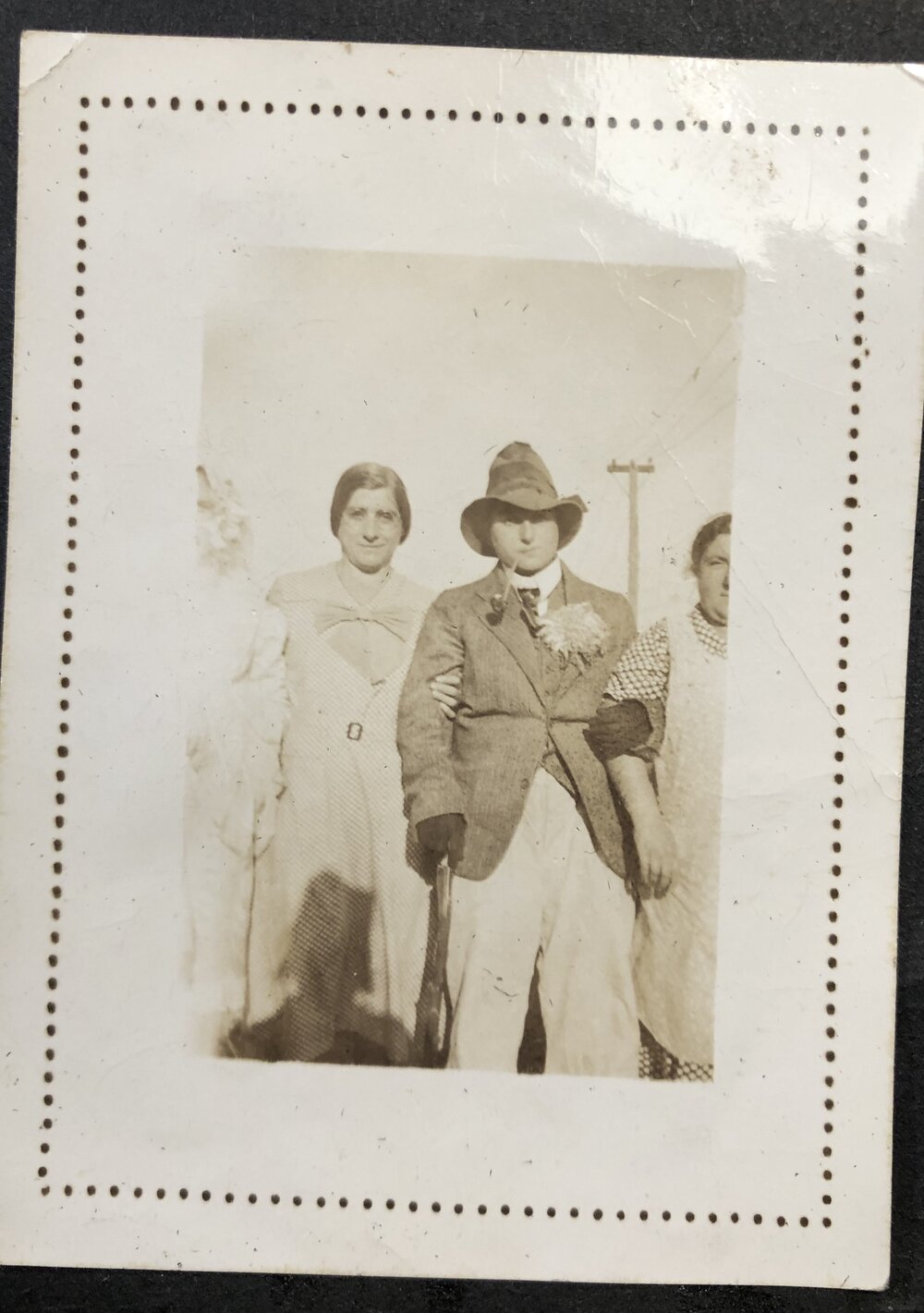

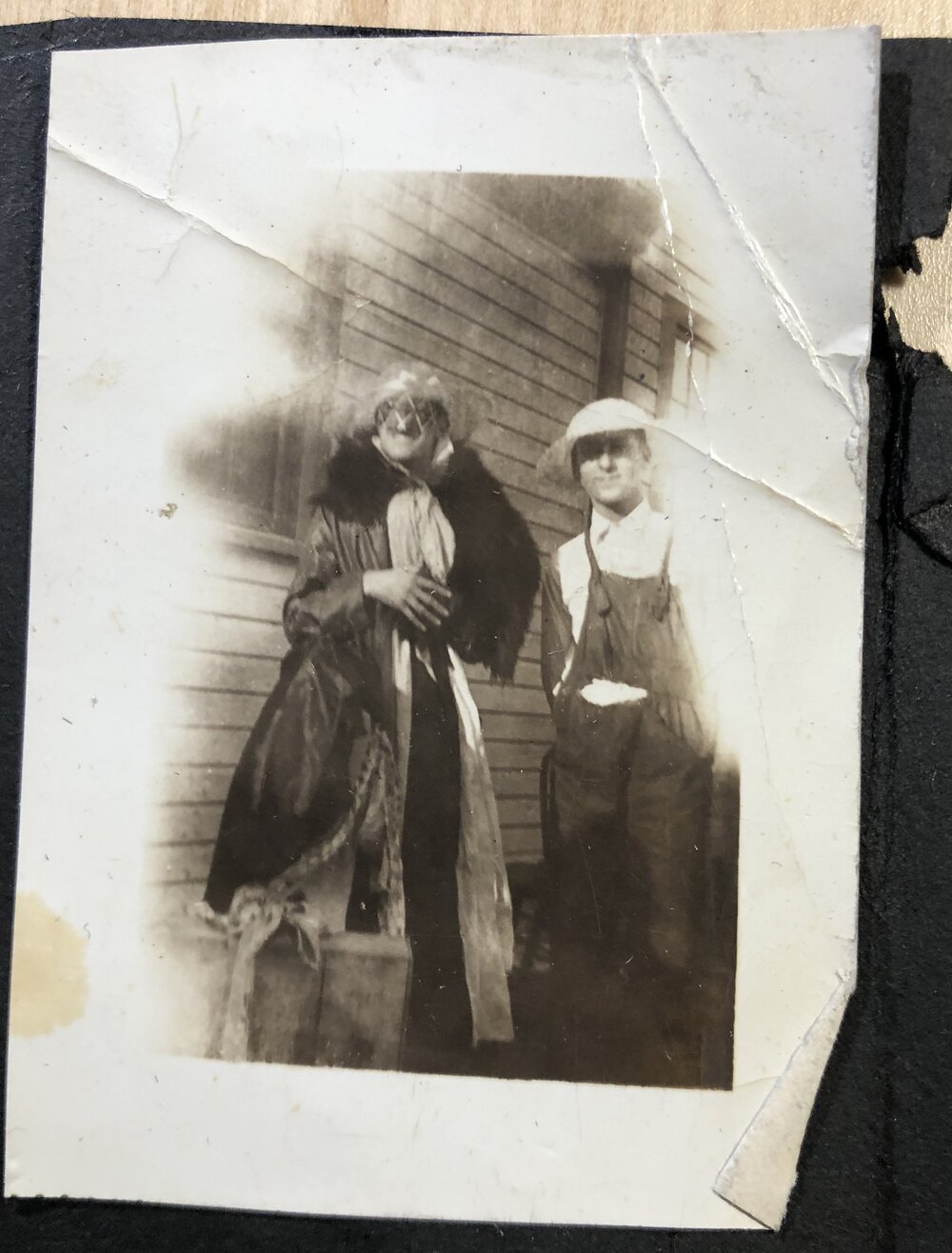

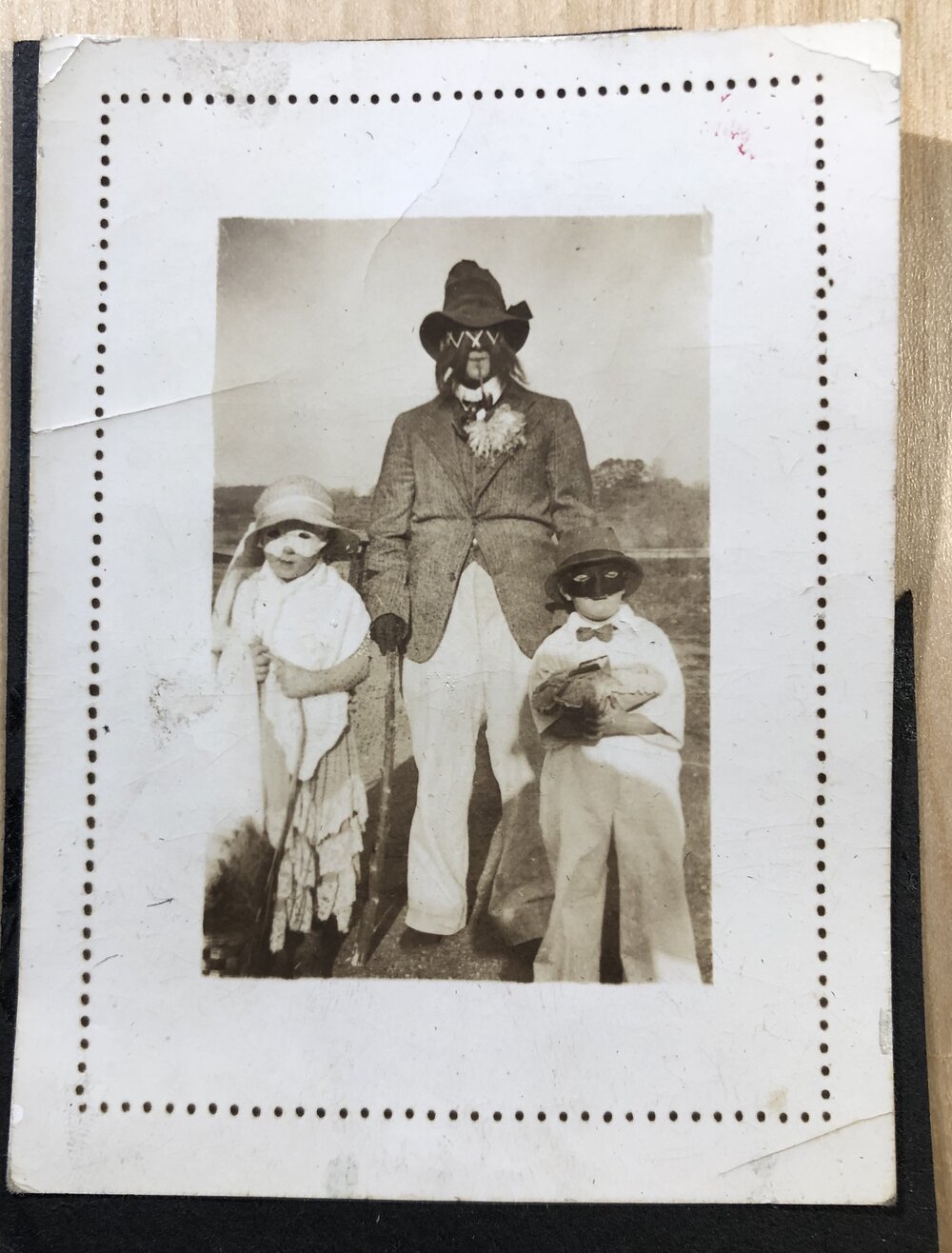

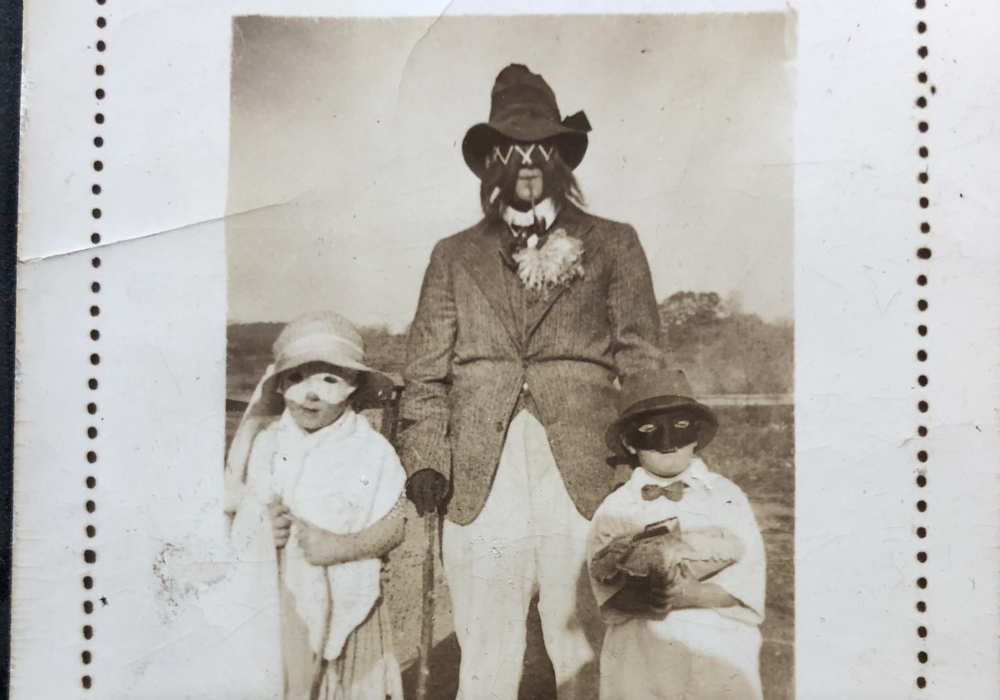

Inside the wrapped mini-package were a series of family photos. “Halloween 1938,” its scrapbook page announced.

These eerie photos eventually provided me with the critical clue that this package was indeed an ARG trailhead of some sort. The spooky doll Dotty can be seen in a corner of one of the photos. Are there other visual clues hiding in plain sight in these photos?

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

The “Second Layer” of the Package

Beneath the mini-package was a larger item, wrapped in more newspaper and surrounded by newspaper padding.

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

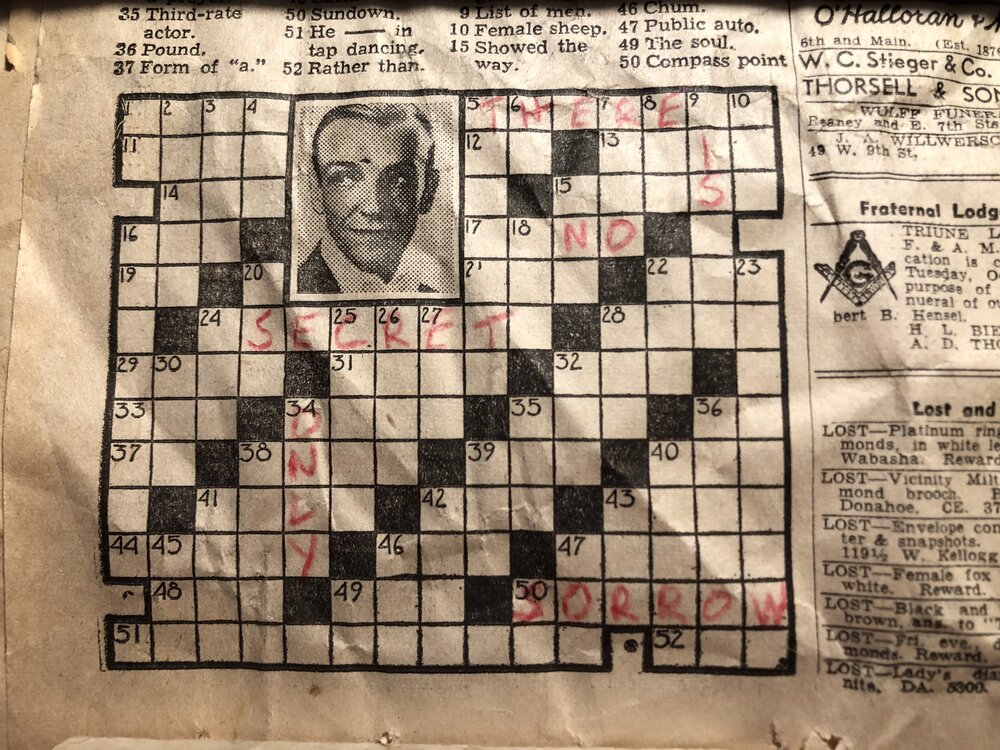

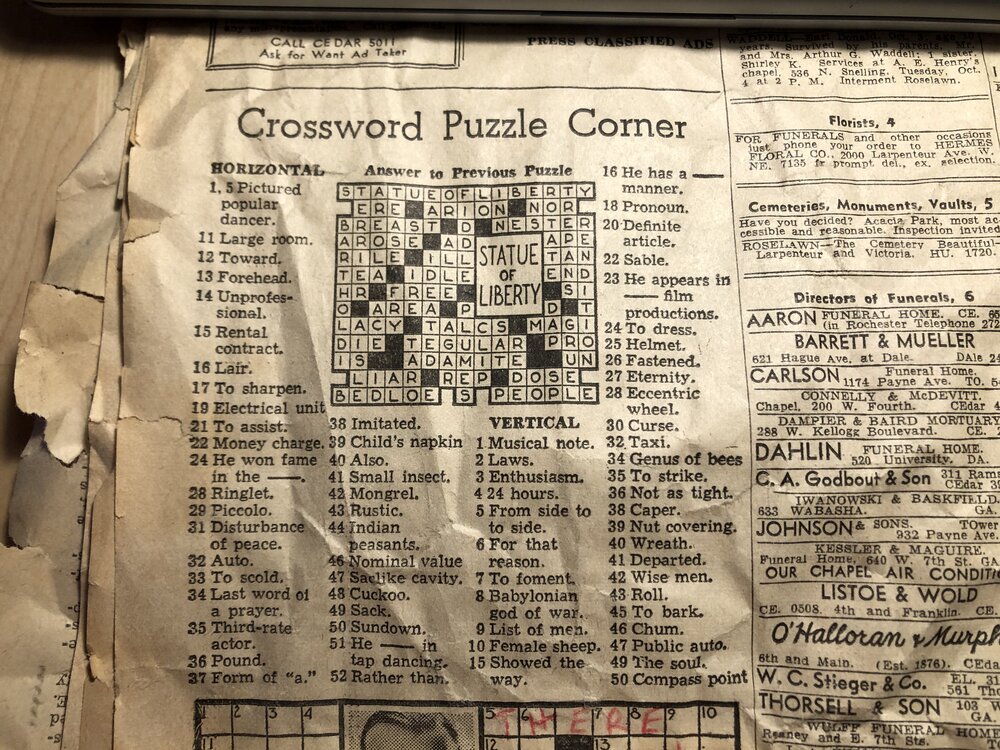

The Crossword Puzzle

One of the newspaper pages contained a crossword puzzle with a distressing message written in red pencil. I’ve included it here, along with the puzzle’s clues. Is this a message simply designed to complement the horrific contents of the box … or is there more to it, and its crossword puzzle?

View fullsize

View fullsize

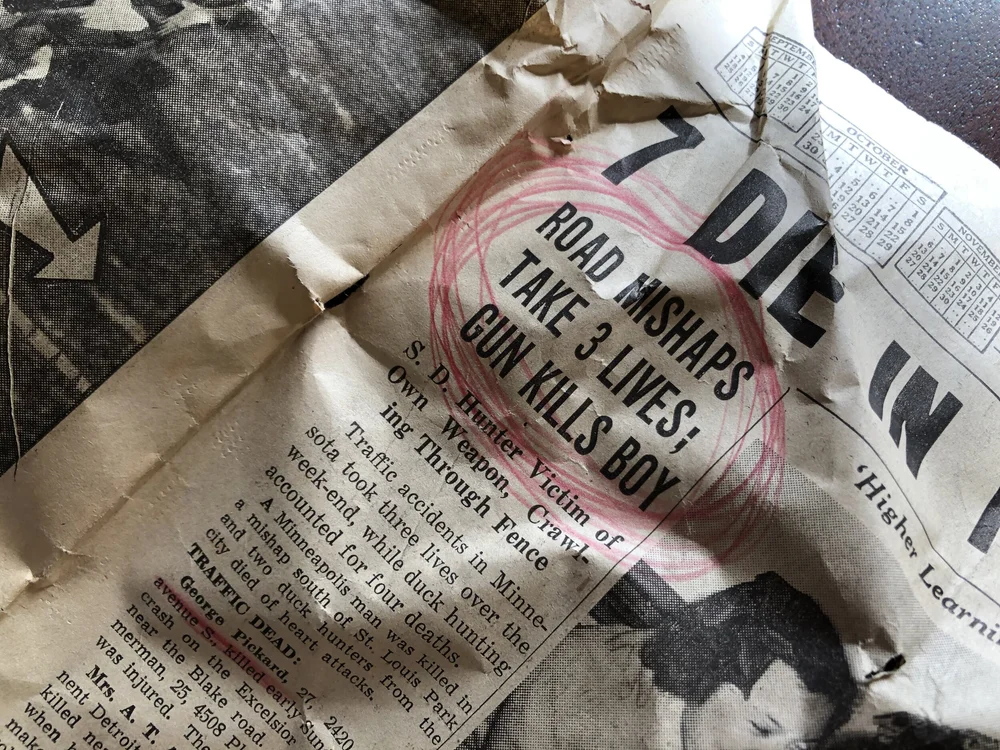

Dotty’s Wrappings

Dotty the ghoulish doll was wrapped in what appeared to be a front page from The Minneapolis Star, published on Oct. 3, 1938. More noteworthy items were highlighted by the sender:

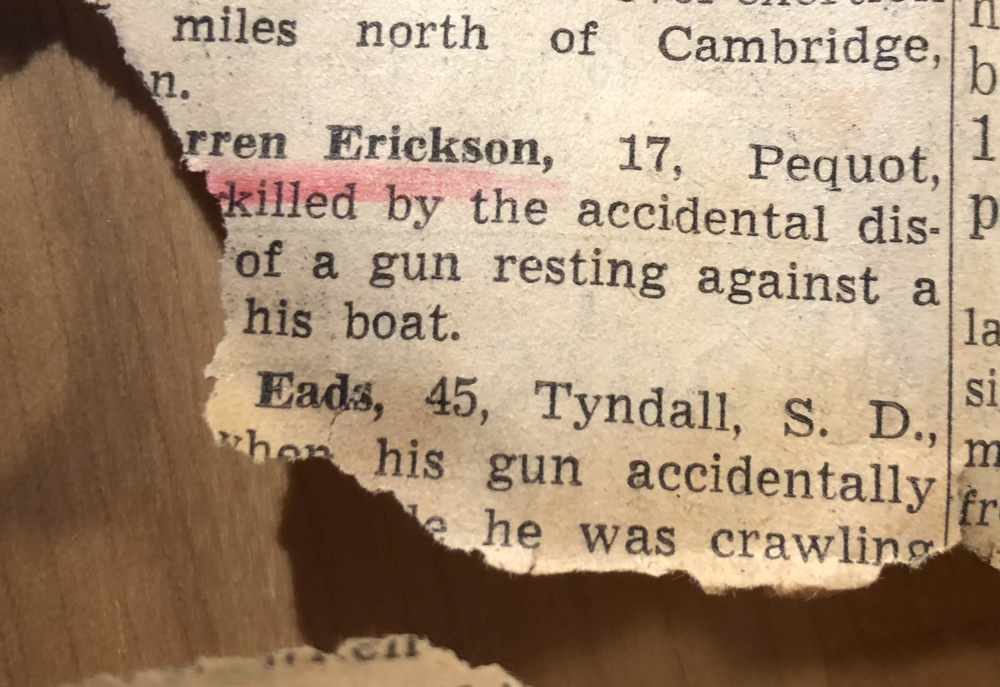

A headline documenting the deaths of two Minnesota residents: George Pickard and Warren Erickson. Pickard died in a car accident; Erickson died when a rifle he’d been traveling with went off accidentally. Pickard was 27. Erickson was 17.

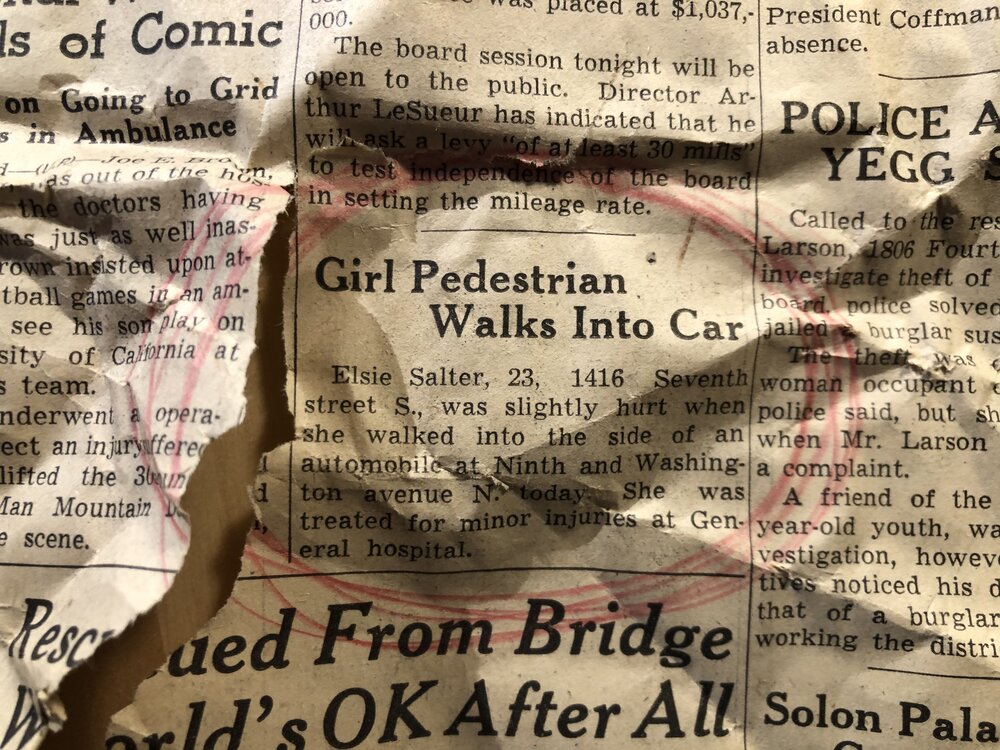

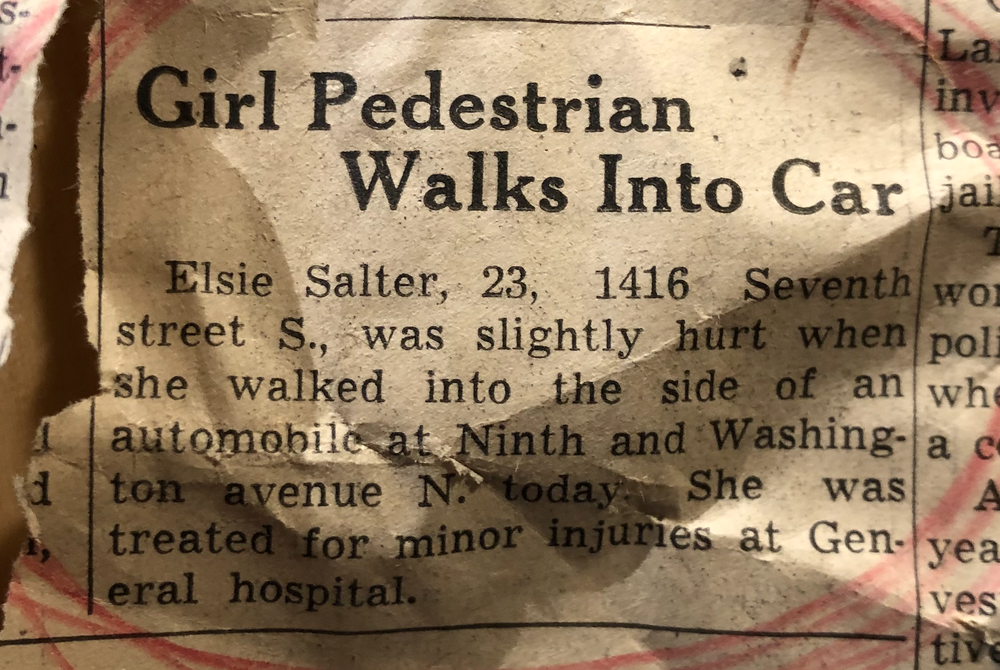

Another story, mentioning a young woman who received medical treatment after “walking into a car.” Elsie Salter was 23 at the time.

When it comes to ARG trailheads and rabbit-holes, the story’s creators—sometimes called “puppet masters”—highlight noteworthy narrative details or clues. What role do these headlines and victims play in this story?

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

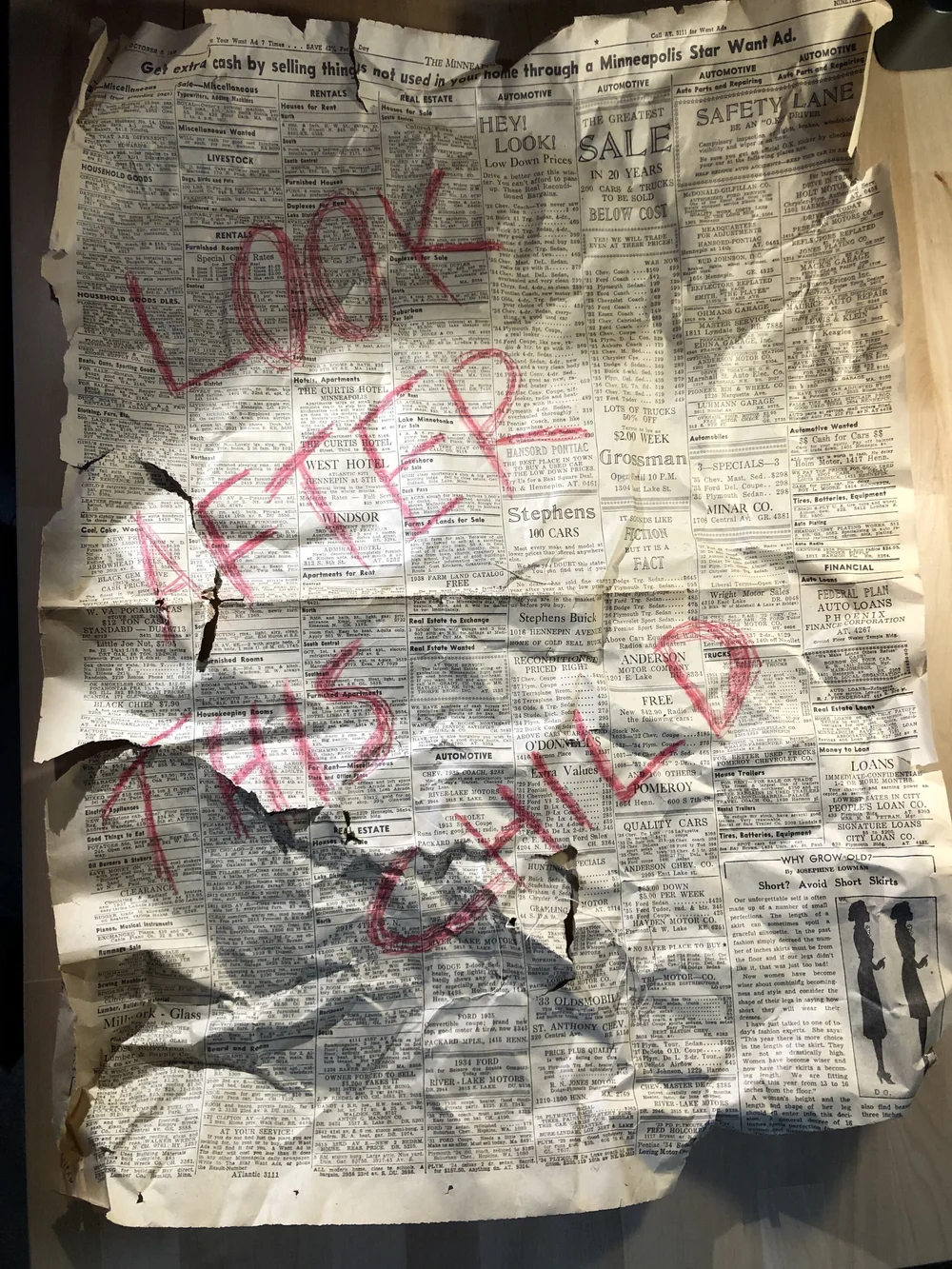

“Look After This Child”

On the underside of the page enshrouding Dotty was a message written in a ragged, frightening letters:

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

Dotty Herself

And then there was the spooky doll Dotty herself, finally freed from the confines of the box. It’s unclear what kind of role Dotty plays in all of this. Her appearance is legit ghoulish, and produced a genuine fright from me when I saw her for the first time.

However, Dotty herself doesn’t seem to provide any additional details for our narrative—other than appearing in one of the “vintage” photos seen above. It doesn’t feel like there’s anything inside her other than stuffing, and there’s nothing written on her clothes or underneath them.

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

What’s Next?

Where do we go from here? I’m leaving that in the capable hands of you and others who want to pursue the clues and unlock the mystery. If you have any questions or requests for additional info, contact me. I’ll update this post as needed.

10 February 2020, 2:48 pm - Interview with Alan Moore, 1999

I was a journalist long before I was a fiction writer and corporate shill. I think I was pretty good at being a newspaperman. Even now, nearly 20 years after leaving the business, I dearly miss the art and craft of print journalism—especially conducting interviews.

During my brief career, I freelanced for Wizard, a magazine that covered the comics industry. I had the great fortune to interview creators such as Neil Gaiman, Warren Ellis and Will Eisner. But my most memorable conversation was with Alan Moore, who was then—and remains—one of my favorite fiction writers.

I interviewed Moore in 1999. I was still in college. Moore had just launched his wildly imaginative America’s Best Comics imprint and was game to talk to Wizard about it. I can only imagine how starstruck and nervous I must’ve sounded during that chat, but Moore was a class act. He was generous with his time, great humored, and accommodated the small detours I took, asking him questions that weren’t precisely about his new comics.

In hindsight, I reckon it was my curiosity to go “off script” with my questions that probably evoked some of the more intriguing moments in the interview, which is posted below.

I consider this conversation with Moore to be one of the coolest gifts the universe has given me over the years. I hope you enjoy it.

“Alan Moore: The Wizard Q&A”

Wizard #95, July 1999

The more comics legend Alan Moore shuns the limelight, the wilder the rumor mill swirls around him.

The rumors say the award-winning writer’s a devil worshipper. You’ll hear he’s got a really creepy voice. He’s a reclusive egomaniac, a mad genius, some kind of humorless goth-type. The Englishman’s been banned by the State Department from traveling to the United States. And if you look at the superspooky black-and-white photograph that accompanies most of Moore’s work, you’d probably believe every word.

But here Moore sits in his Northampton, England home, lighting up a smoke and speaking humbly about his career. Relaxed and cordial, he doesn’t see himself as the writing genius others paint him to be. “The idea of being on some kind of pedestal isn’t as much fun as it looks,” he says. “The fact I don’t go to conventions and tend to eschew celebrity in any way should give you a clue how I feel about that. Okay, so some letter in a fanzine says you’re a genius. Well, for about 10 minutes, you can say, ‘Yes, I probably am a genius.’ But it didn’t take long before I realized that was absurd.”

This isn’t the Alan Moore of the rumor mill. No, the creator of the new America’s Best Comics line is all too human here, smiling and bragging about his two pierced, punky daughters (“Both of them have more metal in their bodies than the average appliance,” he says.) He recounts stories from the early ’90s, when he played in a pop band called The Emperors of Ice Cream: “We had a girlie back-ing band, and I had this wonderful, huge white zoot suit,” he laughs. “But it didn’t work out.”

So Moore didn’t hit the Billboard charts. Big deal. He’s recognized as a pioneer in comic books. Moore began impressing the American audience in 1983 with his reinvention of the modern horror comic in DC Comics’ Swamp Thing. He gave readers the politically-charged V for Vendetta. But Moore is perhaps best known for Watchmen, the 1986 series that gave readers a superhero story without the superheroics. The story rattled the industry, and catapulted Moore to critical acclaim, media attention and superfandom among readers.

In the late 1980s, Moore left DC—mainly over an ownership and royalties dispute over V for Vendetta and Watchmen—vowing to never write for the company again. But now Moore is back at DC, writing his America’s Best Comics line for the DC-owned Wildstorm Productions. He speaks freely about his current relationship with the company, and his new comics line. He also debunks some rumors, explaining why he hates being seen as a comics “god” and about being a practicing magician—not a devil worshipper.

Oh, and the rumor about Moore being banned from America? That’s between him and the State Department. After all, there are some things you just don’t ask a practicing magician…

WIZARD: Over the years, your name has become synonymous with words like “genius,” “visionary” … even “comic book god.” But come on, man. You eat like everyone else. You take a crap like everyone else—

MOORE: And I put my pants on three legs at a time like everyone else. [Laughs] I live in Northampton, where everybody is familiar enough with my untidy and bumbling physical presence to dispel any illusions of deity. Nobody here treats me special, just how I like it.

The notion of celebrity after a while became horrible to me. Since the end of the ’80s, I’ve kept a low profile. Before then, I’d go to conventions and was mobbed everywhere I went. Kids fainted—or had epileptic seizures—when they met me.

WIZARD: The convention experience was that bad for you?

MOORE: Yeah. I went to one of the British conventions during the Watchmen boom, and it was certainly the most highly-attended British conventions; most came because of the press Watchmen was getting. This was a great moment of triumph for comics, mind you. But all I can remember of the entire convention was sitting in a bleak hospitality room, miserable, because I couldn’t go out without attracting a mob. At one point, I was halfway up a stairwell—there was a two- or three-story drop beneath me—with 50 kids, all pressing forward. At the San Diego convention one year, I woke up screaming from a dream of clutching hands.

What do you do? I don’t want to be the celebrity, the center of attention. Sometimes I find myself quite boring, believe it or not, and I don’t want to dwell upon myself every single second of the day.

I’d rather my work maintain my only profile. It doesn’t really matter to readers whether I exist or not, now does it? It’s only the work. I don’t want them to admire my haircut. I don’t want them to admire my complexion or my trim physique. If they enjoy the story, then that’s great. The contact between me and them has successfully been completed, you know?

WIZARD: What’s your contact with DC these days? Although the company’s publishing your new line of comics, there’s no DC logo on any of them.

MOORE: That’s part of the deal [former WildStorm publisher] Jim Lee proposed [when DC acquired WildStorm last year]—that it would be possible to keep America’s Best as far removed from DC as possible. There is nothing on the book that connects it to DC. I mean yes, at the end of the day, it’s DC who’s publishing these books. And yes, I would prefer it if it were otherwise. But it’s a thing I can live with, and as long as we can keep this arm’s-length relationship, there won’t be any problems.

WIZARD: Is there any chance you’ll be writing Swamp Thing or any other DC characters again?

MOORE: I know fans would like to see that, but no. Even if my relationship with DC were different, I’m not sure I’d be interested in working on the characters anyway. They’ve seemed to change in the last 10 years, probably for the better, but they’re not really the characters I want to work with anymore. I don’t really have any nostalgic longings for them. I’m quite happy with the stuff I’m doing.

WIZARD: Let’s talk about that. What was your overall plan for America’s Best Comics when you conceived it?

MOORE: There was a band over here in the ’80s called Pop Will Eat Itself. That name was a great name, a prophetic name. Pop—whether it be popular music, culture or comics—comes to a point where it devours its own past to find something new. Comics have done that; my Supreme work [for Awesome Entertainment that paid homage to Superman] is an example. What I wanted to do was avoid that in this line. So I asked myself, “Is there another way comics could have gone?”

To answer that, you have to trace comics’ roots back to the point of which the modern superhero was born: Superman. If you go back to the stage right before then, you’ll find pulp magazines and newspaper comic strips. The 19th-century fantasy novel. Mythology. Early science fiction. These were the things the comic grew out of. I’ve tried to return to that pre-Superman territory and extrapolate a different future from there.

They’re the parallel world comic books, if you like. I’m just hoping there’s a parallel world audience out there that’s interested in reading them. [Laughs]

WIZARD: There are five ABC books debuting in the next few months. [EDITOR’S NOTE: See sidebar.] Are there plans for any other titles?

MOORE: There is a sixth book we’re thinking of doing, one for artists who can’t commit themselves to an ongoing strip, but who I would be mad not to work with. I’ve been talking to people like Dave Gibbons, Brian Bolland, Glenn Fabry. This is all very formative right now; there’s no schedule for it yet, but it’s something we’re planning for a few months down the line. We also have more six-issue stories planned for The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen.

WIZARD: Has it been difficult finding the time to write all this stuff?

MOORE: I enjoy doing it, frankly. I see this as kind of showing off a bit. “Hey, let’s show off and dazzle the readers.” I don’t indulge myself that often, so what the hell.

WIZARD: You’ve been dazzling readers for about 20 years now. When it comes to having a “favorite writer,” fans and comic book pros almost always drop your name. What’s your reaction to that?

MOORE: It’s very nice, very flattering! It’s nice to know I’m any help at all to my fellow creators—they can rest assured that they’ve been a help to me. As far as the fans still loving my work, I’m very grateful for it. I sort of wish… [pauses] that they had more choice.

WIZARD: What do you mean by that?

MOORE: [Pauses] Remember, you’re talking to Alan “Big in the ’80s” Moore. Watchmen was more than 10 years ago. I don’t want to sound rude or patronizing in any way, but I just wish there had been… [pauses again]. I would have liked to have thought in the ’80s that by now, there would have been some stuff that would have come and made [Watchmen] long forgotten. That would have been perhaps worse for me, but would have been better for the industry. But I’m not sure there’s been work that’s reached as far, or attempted as much.

And that’s not to decry any of the work that’s been along since, because there’s been some very fine work. I don’t know. I’m probably on very shaky ground and I’m probably being very insulting to a lot of people’s work. But anyway, that’s my only regret. But it’s very flattering that people still think very highly of my work.

WIZARD: So what the hell do you do when you’re not writing comics?

MOORE: Oooh. That’s a good question. I’ve spent the last five years—and I’ve made no secret about this—being intensely committed to the study of magic and the occult.

Most of my life, I didn’t have much sympathy for the occult. If you go into a lot of occult shops, you’ll find people with yawning emotional gaps in their lives who try to cram them full with some outlandish belief system. But I started to look at people who I could not dismiss. People like Dr. John Dee, a man who invented the concept of the British Empire, wrote the definitive boom on navigation and was Queen Elizabeth’s court astrologer. A brilliant man in numerous respects. But he spent the last half of his life transcribing this strange stuff which he believed to be the “language of angels.”

WIZARD: That’s where everyone says, “That’s when he went crazy.”

MOORE: Right. But I found it harder to dismiss. I thought it wasn’t fair that this man was a genius apart from this stuff. I thought I should look at it a bit more closely. So on my 40th birthday, I decided that rather than have a mid-life crisis, I’d do something a bit more mad. I decided to explore the ideas behind magic. To me, magic has an awful lot to do with creativity, and creativity has an awful lot to do with magic.

So if I wanted to find out more about creativity, I’d have to take that last step over the boundary of the rational.

WIZARD: What did you do?

MOORE: I read lots of books. Studied. Tried to think my way into it. Then, doing a ritual with a friend of mind back in January ’94, something happened, something difficult to describe in detail. There was some kind of influx of something, something… [pauses]. It happened to both of us at the same time. Bear in mind, I know this is completely mad. It can’t possibly be so. But at the time, if felt like something like a god—some extraordinary intelligence or consciousness—was rushing through both of us.

I was completely stunned. I spent the next few days thinking, “Dare I tell anybody about this?” But I decided to go for it. People were a little worried at first, but they were also very curious because I was speaking with conviction. Now, some of them practice with me. [Laughs] Here’s the subtext to my magical experience: I’m going mad, and I’m taking as many people with me as I can.

WIZARD: [Laughs] So, what do you practice?

MOORE: Qabalah is one. It’s part of the Western occult tradition. It includes all of the religious systems: Greek, Egyptian, Norse, Christian, it’s all there. It’s seen as a map of the universe on one level, but it’s also seen as a map of you, the individual. I might do a ritual that involves the god Mercury. You can have a dialogue with that energy, that cluster of ideas we label with the name Mercury.

WIZARD: You’ve had a conversation with the god Mercury.

MOORE: Maybe. During the experience, you believe you are actually talking to a god. Who’s to say if you are, or if you’re not? I’ve tried to keep an open mind about it. I tell myself, “One one level, this is a hallucination. This is an element of my own personality, some subconscious element of myself.” On the other hand, I also have to allow that this might be something completely beyond my personality, a higher entity. I mean, if it barks like a god and smells like a god, it’s probably a god. [Laughs]

WIZARD: [Laughs] At least you have a sense of humor about it.

MOORE: You have to. Most of this is a lot less dramatic than you’d suppose. It’s reading a bunch of books, and every three months or so, doing a working. We’ll do a proper ritual working, something peculiar will happen, and then we’ll get our strength back in a few months and do it again.

WIZARD: That dispels the image that some readers have of you—that you’re some kind of unapproachable “goth genius.” I bet they get it from that black-and-white photo of you. You look dangerous.

MOORE: [Chuckles] Ah, the photo. That’s all [photographer] Mitch Jenkins. He always goes for the dark, scary look. I don’t know. To me, my life is completely normal. I have no desire to have a dark allure. I have my hair like this because, frankly, I think it looks gorgeous. [Laughs] Those rolling, natural highlights, you know.

But I’m sure that looks dangerous to some people. And from experience, I know that if they met me in some foggy circumstance, they’d find me a bit alarming.

WIZARD: You have a great “Alan Moore looks like the bogeyman” story, don’t you?

MOORE: [Laughs] I remember walking though a park here in Northampton—a park notorious for its muggings and the like—during a foggy night. I heard some guys coming, probably from the pub or something, and I knew our paths would intersect. They were loud and boisterous. We finally crossed paths in the fog, and they stopped dead in their tracks. I kept walking. Finally one of them gave this nervous laugh.

WIZARD: Did he say anything?

MOORE: Yeah. He said, [in a fearful voice] “I didn’t know what it was.”

# # #

SIDEBAR 1: Vital Stats

Name: Alan Moore

Occupation: Comic book writer

Born: November 18, 1953 in Northampton, England

Base of Operations: Northampton, England

Career Highlights: Has won more than 20 awards since he landed on the comics scene in 1980. Became a superstar with his American comic debut on Saga of the Swamp Thing in 1983 and a bona fide legend with Watchmen in 1986, which many believe to be the best comic series ever done. Keeping a lower profile in the ’90s, Moore recently launched his new comics line, America’s Best Comics, from DC/Wildstorm.

Best “Stranger Than Fiction” Moment: “I was eating sandwiches at a restaurant in London; this was right after I created [Swamp Thing’s] John Constantine. I looked up, and walking by was a man who looked just like Constantine: the cigarette, the trench coat, everything. He looked at me, winked, nodded and turned the corner. It was a chilly moment. I could have followed him … but I decided to leave the café instead.”

# # #

SIDEBAR 2: ABC’s 1,2,3

When Alan Moore conceived his America’s Best Comics line, he wanted “pre-Superman” heroes inspired by 19th-century literature, pulp magazines and mythology. Here, Moore introduces us to ABC’s major players:

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen

Set in 1898, this book stars characters of 19th-century fiction—folks like Mr. Hyde, the Invisible Man, Captain Nemo, Allan Quartermain—who all exist in the same world and team up to stop an international conspiracy.

Tom Strong

Inspired by pulp icons like Doc Strange, Tom Strong is a hero who’s battled evil since the beginning of the century. A bizarre supporting cast (including a talking moneky and a steam-powered butler) assists him through his exploits. “This stuff is fun. It’s all shipwrecks and beautiful women and jungle kingdoms,” Moore says.

Top 10

Neopolis is a super city … literally. “Everyone in this book—the cabbies, the winos—are superheroes,” Moore says. This May-shipping book’s about Precinct 10, a police force created to take care of Neopolis’ supercrime. Inspired by shows like “NYPD Blue,” Moore’s going to have several storylines going on at once here.

Promethea

Debuting in June, Promethea stars a warrior from the realm Immateria. “Promethea is hard to describe without blowing the first few issues,” Moore explains. “She’s an embodiment of the human imagination. Promethea’s a fiction who’s somehow crossed over into our world. I want to babble her origin away, but that would spoil the readers’ enjoyment.”

Tomorrow Stories

July’s anthology features stories starring new heroes. The Spirit-like Greyshirt fights crime in the natural gas-powered Indigo City. Boy inventor Jack B. Quick spends his time building miniature solar systems and elevators to the moon. The bored, rich girl Cobweb fights crime for fun, and says Moore, “wears a transparent costume.”

# # #

26 December 2019, 9:20 pm - A Lesson from Richard Simmons

I finished listening to Missing Richard Simmons yesterday. It was pretty good. Check it out.

Back when I was a newspaper reporter, I interviewed Richard Simmons. Predictably, he was a hoot. During the interview, I asked him for, like, "5 tips for living healthy" or something like that for a sidebar. One of them stuck with me:

"Don't walk among your ruins," he warned. Meaning, don't ruminate over past failures. Experience them, acknowledge them, learn from them, and then move on. Don't stay there. Take the lesson and mosey. Don't stay trapped in the past.

The older I get, the more I find myself wanting to walk among my ruins. I often think of Simmons' advice.

You know what? It works.

23 March 2017, 4:57 pm - All Attitude.

18 March 2017, 4:31 am

18 March 2017, 4:31 am - Pass the Chips

My new personal mantra when it comes to writing:

Potato chips, not pearls.

Meaning: Nearly everything I write will be consumed quickly and compulsively. It's disposable. I must move fast to keep pace. Be less precious. Make it peppy, hit my goal, drop the mic and GTFO. Do it all over again.

I'm realizing the greatest sin I've probably committed as a writer—for both my non-fiction and fiction work—is obsessing about craft. Only I (and wanker writers like me) see the seams, the stitch-marks, the misplaced commas.

Nearly everyone else just wants yummy potato chips.

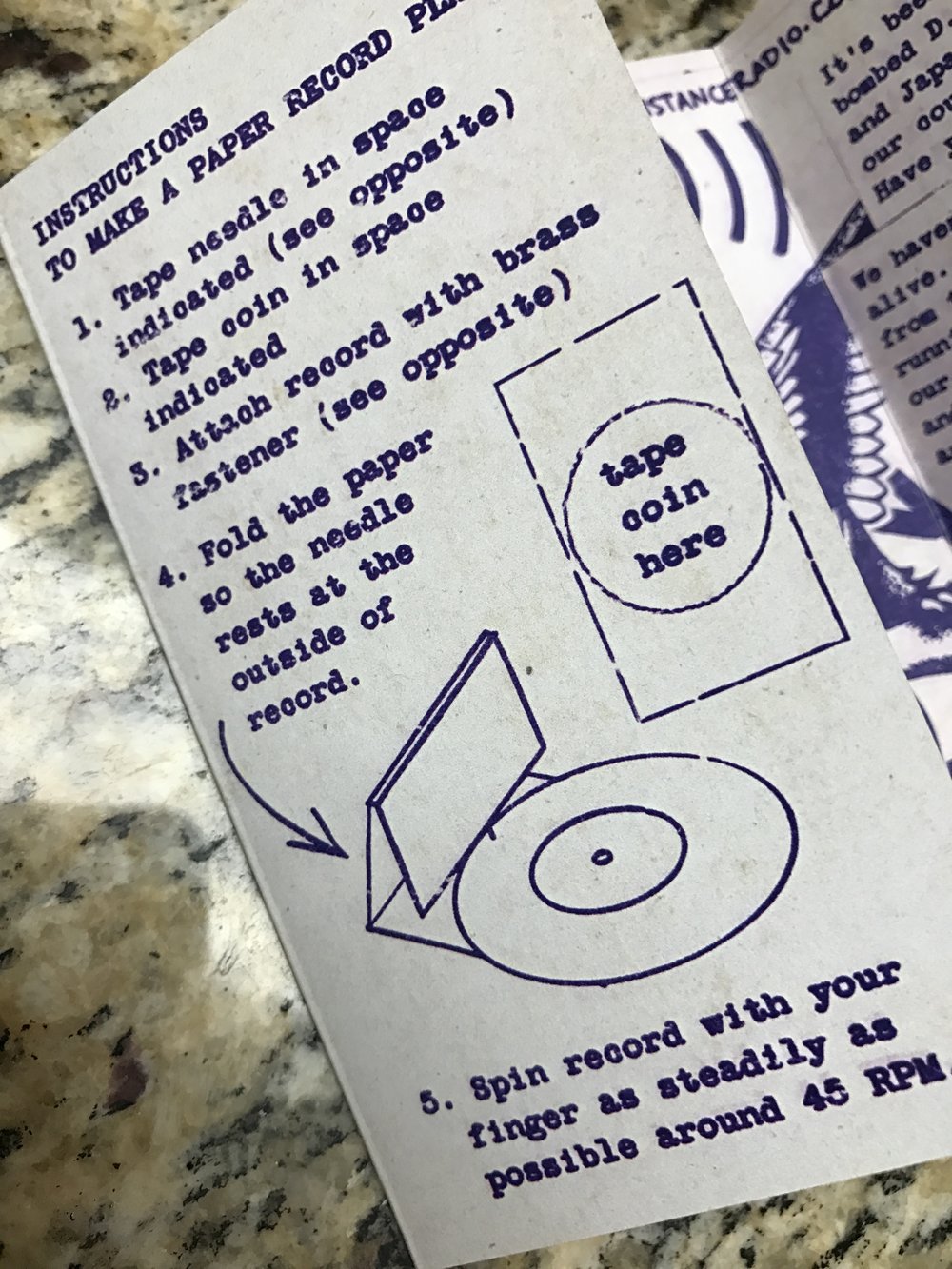

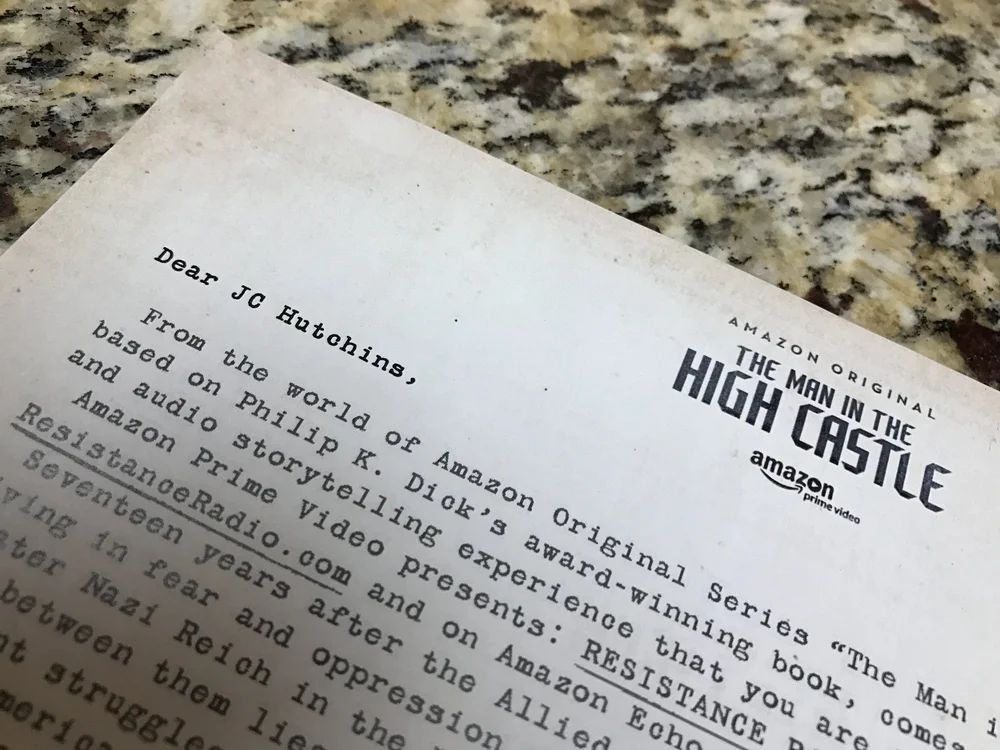

17 March 2017, 10:47 pm - Resistance Radio

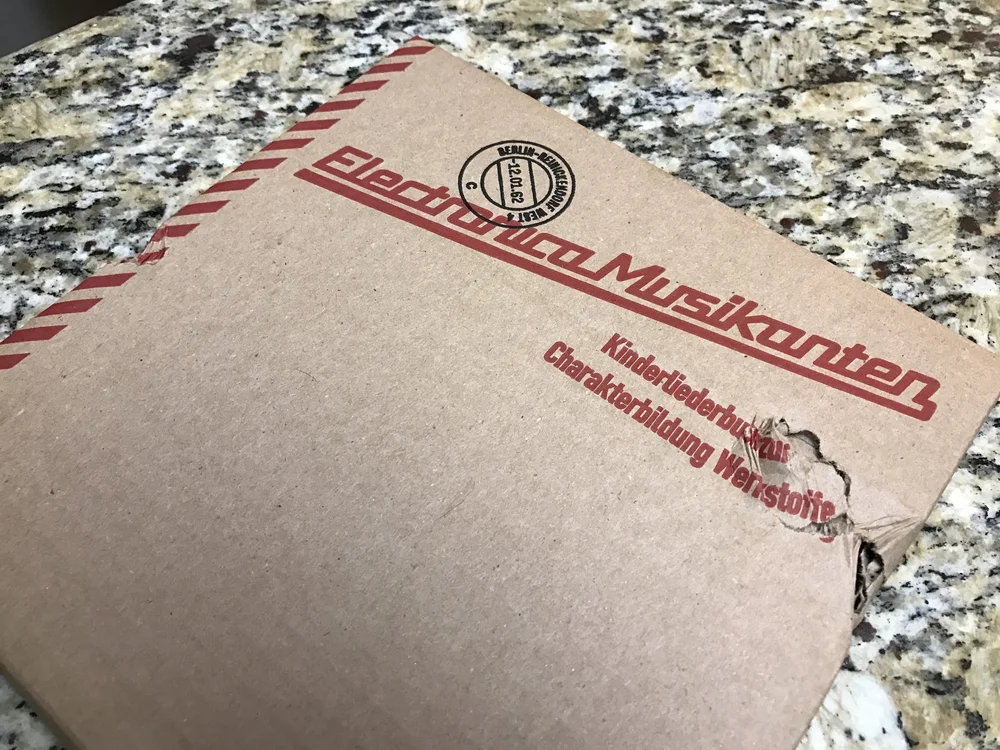

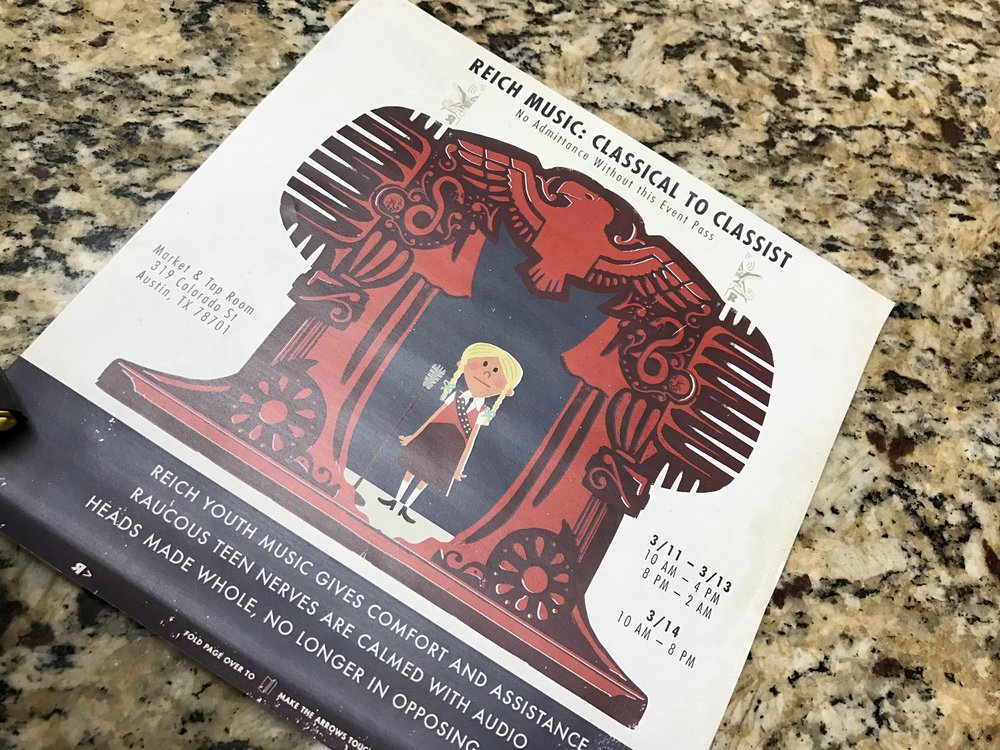

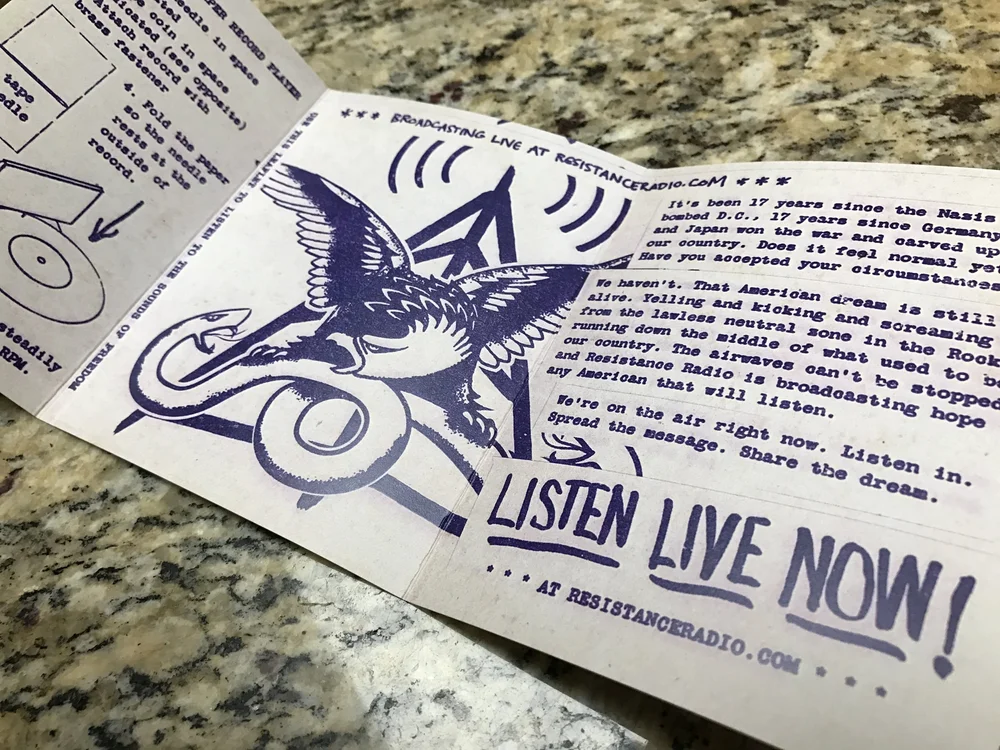

WOW! A special package was delivered to my home last night, sent from an ALTERNATE 1960s. In this alt-world, the fascists won the war, and America ain't what it oughta be. (Sound familiar?)

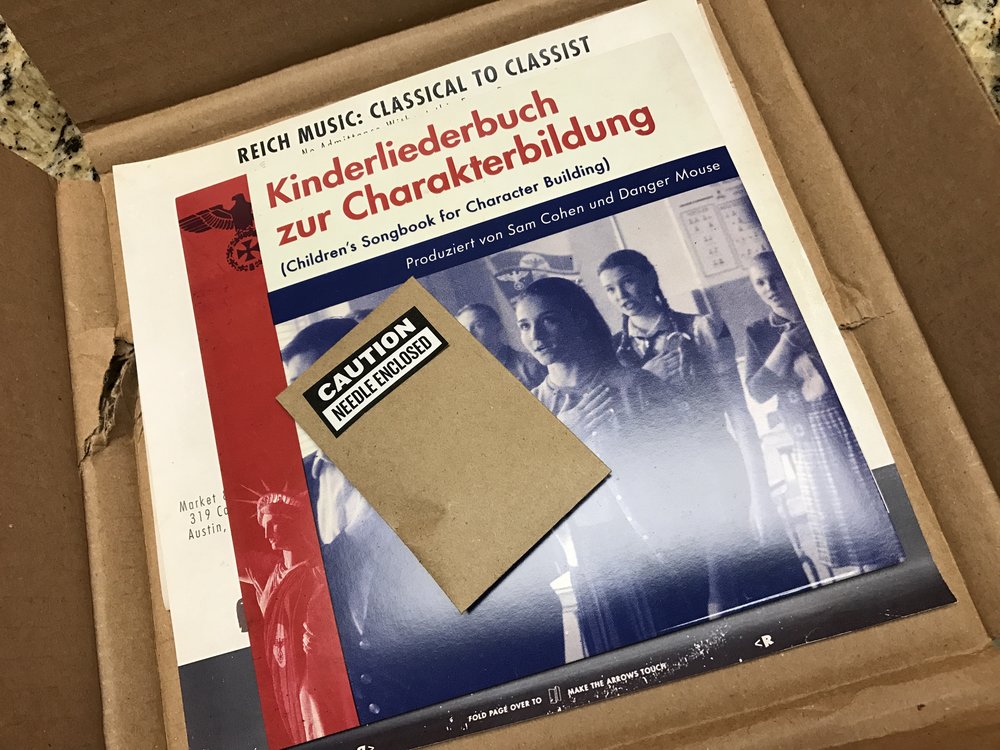

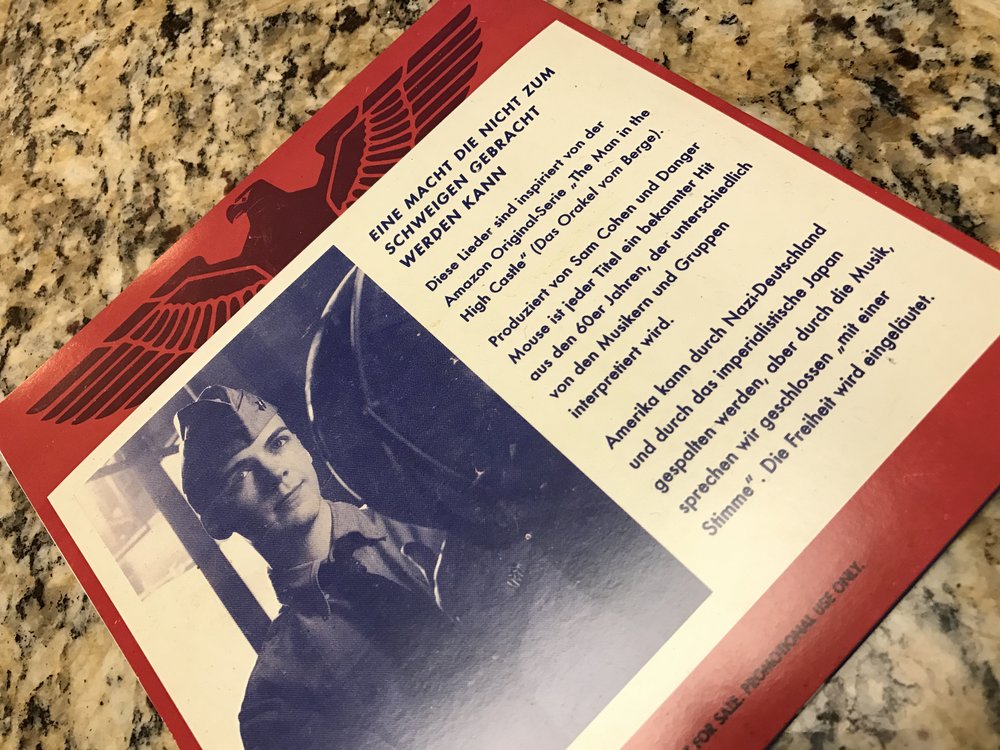

This is brilliant work from my dear friends at Campfire. It's a bona fide artifact from another world. It looks and feels absolutely authentic. And there's a story here—a "tangible narrative," as I call this stuff.

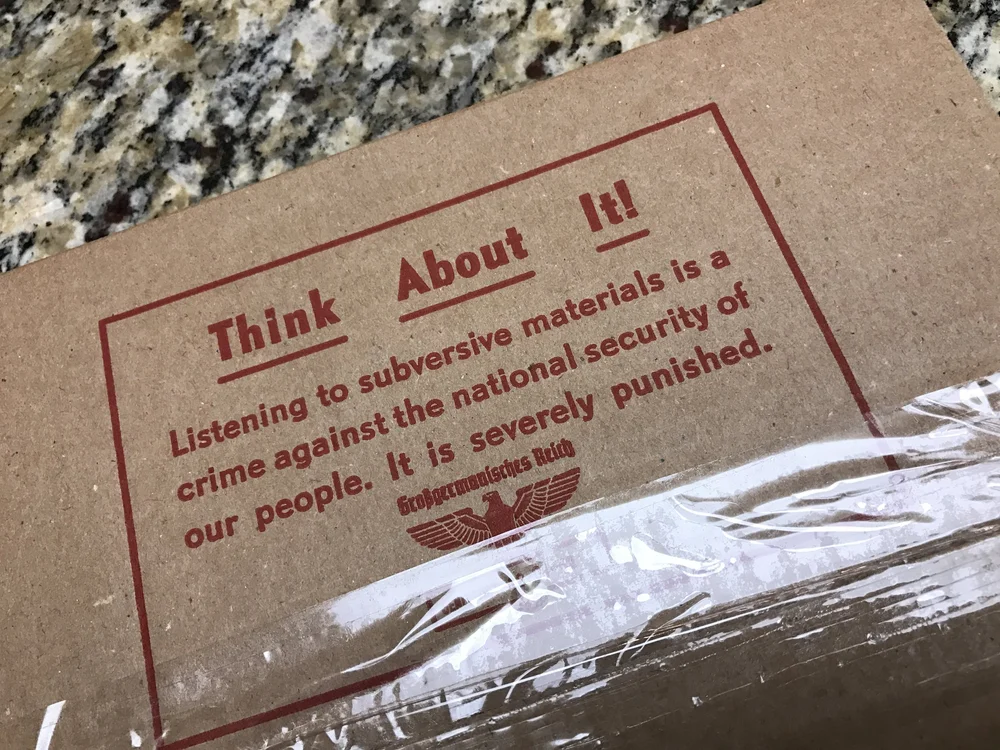

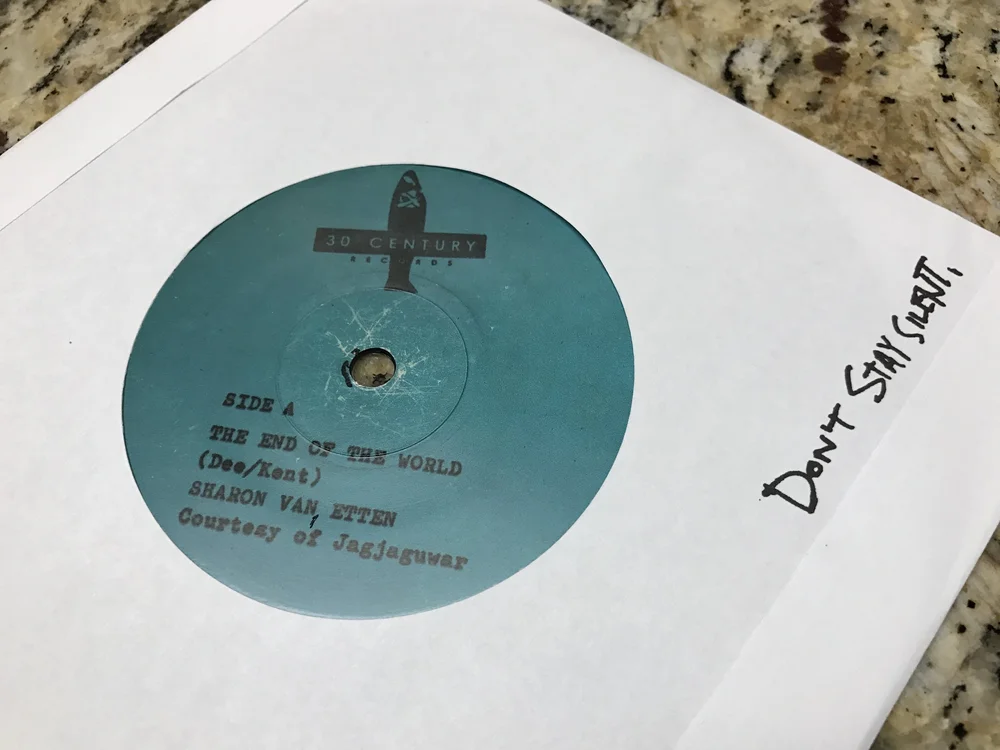

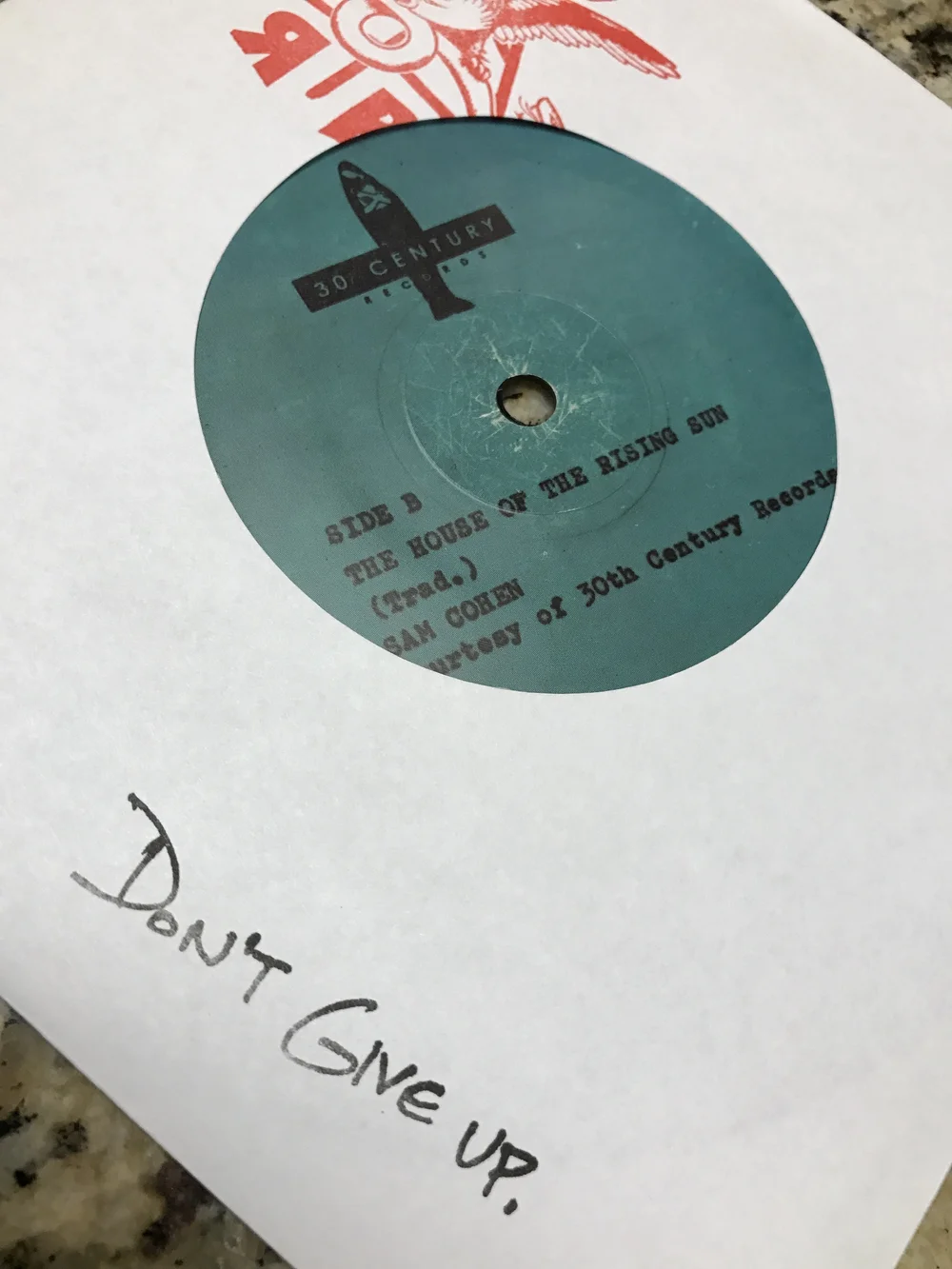

Take a peek at these unboxing pictures. See the story. On the surface, this looks like something sent from a governmental agency. But a member of the Resistance has slipped a subversive record into the sleeve of an "approved music" album. They've given instructions on how to play the record, should you not have an record player. And there's more, lurking in puzzles hiding in plain sight.

It's a meticulously, lovingly crafted piece of fiction. And it's a love letter to "The Man in the High Castle," the TV show it elegantly promotes. So is the incredible Resistance Radio website, also created by Campfire. It's a must-visit: http://resistanceradio.com .

What a terrific experience. In particular, the surprise and delight of finding a "banned" record inside a "legit" record sleeve was a wonderful moment I'll remember for a long time.

8 March 2017, 4:05 pm - 'I, Me, Mine' Journalism

So. Three paragraphs into this 2,500-word feature story about an icon in the video games biz, and the reporter injects himself into the story. A brief skimming of the piece suggests he will do this again and again and again.

Video game journalists—and indeed, many online writers who never went to J-school—do this all the time. It's like catnip. They can't help themselves. They cannot fathom the concept that the narrative is not, in fact, about them.

Yes, I'm grousing about this again. (I whine about this often on Facebook.) Maybe it's an age thing; a practice that undisciplined young writers, overseen by undisciplined editors, can't help but do. Maybe it's a generational narrative trend. Maybe it's a games-industry thing. Maybe it's a lack of formal editorial training. (Or alternately, a kind of formal editorial training that I deeply disapprove of.)

I'm totally get-off-my-lawning here, I know. I remind myself that my thinking must represent the ossified, arthritic perspective of someone who learned journalism before the Internet. (See? Right there. I capitalized Internet, per the AP Stylebook circa 1998.) I must be out of touch. I'm a tone-deaf geezer.

Unless I'm not. I flail and fail at most things I do. I'm not the sharpest tool in the shed. But I know good storytelling—non-fiction narrative in particular. It's the only thing I've ever been really good at. I know how that house is built.

And where I come from, good journalists don't talk about themselves in their stories. They are observers. Facilitators. They are the radio through which the song is played. They are never the stars.

16 February 2017, 2:57 pm - More Episodes? Get the App