Cardionerds: A Cardiology Podcast

CardioNerds

Cardionerds is a medical cardiology podcast and platform that democratizes cardiovascular education and brings high yield cardiovascular concepts in a fun and engaging format to listeners of all levels.

- 43 minutes 3 seconds367. GLP-1 Agonists: Clinical Implementation of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists with Dr. Neha Pagidapati

CardioNerds (Drs. Gurleen Kaur and Richard Ferraro) and episode FIT Lead Dr. Spencer Carter (Cardiology Fellow at UT Southwestern) discuss the clinical implementation of GLP-1 receptor agonists with Dr. Neha Pagidapati (Faculty at Duke University School of Medicine). In this episode of the CardioNerds Cardiovascular Prevention Series, we discuss the clinical implementation of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists. We cover the clinical indications, metabolic and cardiovascular benefits, and potential limitations of these emerging and exciting therapies. Show notes were drafted by Dr. Spencer Carter. Audio editing was performed by CardioNerds Academy Intern, student Dr. Pacey Wetstein.

This episode was produced in collaboration with the American Society of Preventive Cardiology (ASPC) with independent medical education grant support from Novo Nordisk. See below for continuing medical education credit.

Claim CME for this episode HERE.

US Cardiology Review is now the official journal of CardioNerds! Submit your manuscript here.

CardioNerds Prevention Page

CardioNerds Episode Page

CardioNerds Academy

Cardionerds Healy Honor RollCardioNerds Journal Club

Subscribe to The Heartbeat Newsletter!

Check out CardioNerds SWAG!

Become a CardioNerds Patron!Pearls and Quotes – Clinical Implementation of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists

- GLP-1 agonists work through a variety of mechanisms to counteract metabolic disease. They increase insulin secretion, inhibit glucagon secretion, slow gastric motility, and increase satiety to limit excess energy intake.

- Patients with type II diabetes and an elevated risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease should be considered for GLP-1 agonist therapy regardless of hemoglobin A1c.

- GLP-1 agonists offer significant ASCVD risk reduction even in the absence of diabetes. Newer data suggest a significant reduction in cardiovascular events with GLP-1 agonist therapy in patients who are overweight or obese and have a prior history of heart disease.

- GLP-1 agonists should generally be avoided in patients with a history of medullary thyroid cancer or MEN2. As these medications slow gastric emptying, relative contraindications include history of recurrent pancreatitis and gastroparesis.

- GLP-1 agonists should be initially prescribed at the lowest dose and slowly uptitrated to avoid gastrointestinal side effects.

Show notes – Clinical Implementation of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists

What were the groundbreaking findings of the STEP1 and SURMOUNT-1 trials and how these impact cardiovascular wellness?

- The STEP1 and SURMOUNT trials demonstrated sustained clinically relevant reduction in body weight with semaglutide and tripeptide, respectively, in patients with overweight and obesity. As obesity is an important risk factor for the development of cardiovascular disease, weight reduction meaningfully contributes to cardiovascular wellness.

What were the findings of the LEADER trial and their implications for patients with type II diabetes and high cardiovascular risk?

- The LEADER trial demonstrated a significant reduction in the rate of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke in patients with type II diabetes treated with liraglutide. GLP-1 receptor agonist therapy should be considered in all patients with type II diabetes and elevated ASCVD risk regardless of A1c or current hyperglycemic therapy.

What are current indications for GLP1 agonists in the context of cardiometabolic disease.

- GLP-1 receptor agonists should be considered in patients with type II diabetes and high ASCVD risk OR patients without diabetes who are overweight/obese and have a history of cardiovascular disease.

What are important side effects or contraindications to GLP1 agents when used for cardiovascular risk reduction and wellness?

- GLP-1 receptor agonists should be avoided in patients with a history of medullary thyroid cancer or MEN2. Relative contraindications include recurrent pancreatitis, gastroparesis, or ongoing unexplained gastrointestinal symptoms.

What are practical concerns associated with GLP-1 use, and how can these be overcome?

- Affordability and availability remain the leading practical limitations for GLP-1 receptor agonist therapies. Many insurance companies will cover semaglutide and tirzepatide for patients with diabetes. Obtaining coverage may be difficult otherwise, but this is an evolving field as more clinical trial data emerge. Beware of unauthentic/alternate formulations of these medications, as they tend not to be FDA-regulated and can pose health risks. Some patients express concern about injectable therapies, but GLP-1 injectors are typically very well tolerated and easy to use.

References – Clinical Implementation of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists

- Brown, E., Heerspink, H. J., Cuthbertson, D. J., & Wilding, J. P. (2021). SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists: established and emerging indications. The Lancet, 398(10296), 262-276.

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673621005365

- Wilding, J. P., Batterham, R. L., Calanna, S., Davies, M., Van Gaal, L. F., Lingvay, I., … & Kushner, R. F. (2021). Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. New England Journal of Medicine.

- https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2032183

- Müller, T. D., Blüher, M., Tschöp, M. H., & DiMarchi, R. D. (2022). Anti-obesity drug discovery: advances and challenges. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 21(3), 201-223.

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41573-021-00337-8

- Jastreboff, A. M., Aronne, L. J., Ahmad, N. N., Wharton, S., Connery, L., Alves, B., … & Stefanski, A. (2022). Tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity. New England Journal of Medicine, 387(3), 205-216.

- https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2206038

- Lincoff, M, Brown-Frandsen K, Colhoun H, et al. Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Obesity without Diabetes. (2023). 389(24):2221-2232.

- https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2307563

- Eberly, L, Yang L, Essien U, et al. (2021). Racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic inequities in glucagon-like-peptide-1 receptor agonist use among patients with diabetes in the US; 2(12):e214182.

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8796881/

3 May 2024, 4:38 am

3 May 2024, 4:38 am - 44 minutes 40 seconds366. Digital Health: Integrating Digital Health into Practice with Dr. Alexis Beatty and Dr. Seth Martin

CardioNerds (Dr. Dan Ambinder), Dr. Nino Isakadze (EP Fellow at Johns Hopkins Hospital), and Dr. Karan Desai (Cardiology Faculty at Johns Hopkins Hospital) join Digital Health Experts, Dr. Alexis Beatty (Cardiologist and associate professor in the department of epidemiology and biostatistics at UCSF) and Dr. Seth Martin (Director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Mobile Technologies to Achieve Equity in Cardiovascular Health (mTECH), which is part of the American Heart Association (AHA) Strategically Focused Research Networks on Health Technology & Innovation) for another installment of the Digital Health Series. In this specific episode, we discuss pearls, pitfalls, and everything in between for emerging digital health innovators. This series is supported by an ACC Chapter Grant in collaboration with Corrie Health. Audio editing by CardioNerds Academy Intern, student doctor Shivani Reddy.

In this series, supported by an ACC Chapter Grant and in collaboration with Corrie Health, we hope to provide all CardioNerds out there a primer on the role of digital heath in cardiovascular medicine. Use of versatile hardware and software devices is skyrocketing in everyday life. This provides unique platforms to support healthcare management outside the walls of the hospital for patients with or at risk for cardiovascular disease. In addition, evolution of artificial intelligence, machine learning, and telemedicine is augmenting clinical decision making at a new level fueling a revolution in cardiovascular disease care delivery. Digital health has the potential to bridge the gap in healthcare access, lower costs of healthcare and promote equitable delivery of evidence-based care to patients.

This CardioNerds Digital Health series is made possible by contributions of stellar fellow leads and expert faculty from several programs, led by series co-chairs, Dr. Nino Isakadze and Dr. Karan Desai.

CardioNerds Digital Health Series Page

CardioNerds Episode Page

CardioNerds Academy

Cardionerds Healy Honor RollCardioNerds Journal Club

Subscribe to The Heartbeat Newsletter!

Check out CardioNerds SWAG!

Become a CardioNerds Patron!25 April 2024, 12:58 pm - 57 minutes 10 seconds365: CardioOncology: Cardiotoxicity of Novel Immunotherapies with Dr. Tomas Neilan

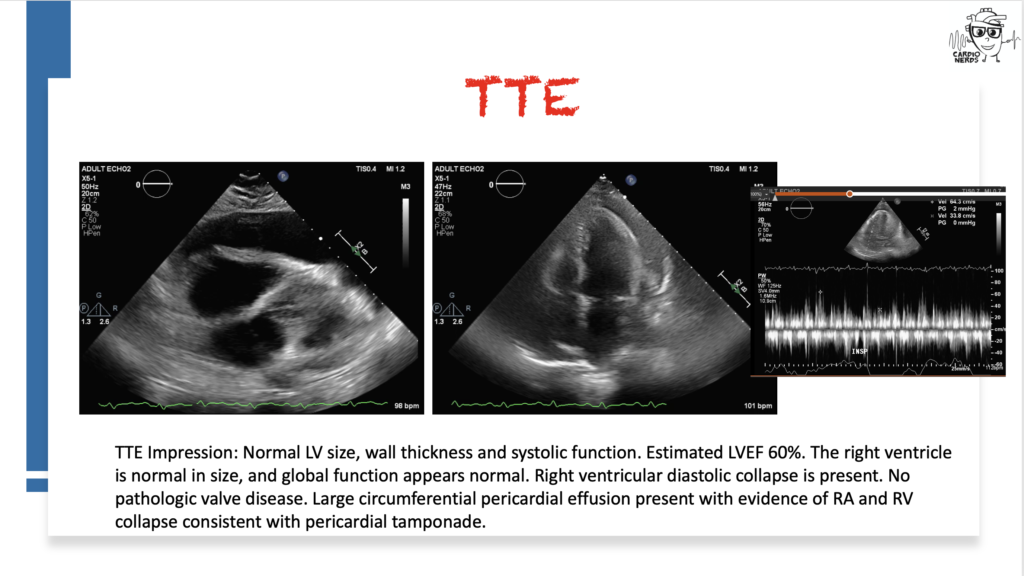

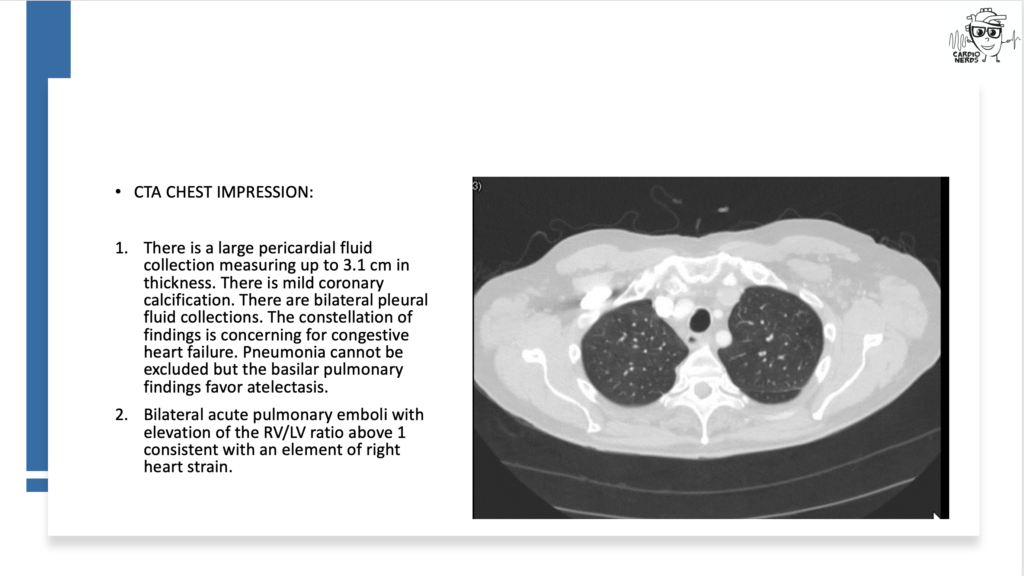

Immunotherapy is a type of novel cancer therapy that leverages the body’s own immune system to target cancer cells. In this episode, we focused on the most common type of immunotherapy: immune checkpoint inhibitors or ICIs. ICIs are monoclonal antibodies targeting immune “checkpoints” or brakes to enhance T-cell recognition against tumors. ICI has become a pillar in cancer care, with over 100 approvals and 5,000 ongoing trials. ICIs can lead to non-specific activation of the immune system, causing off-target adverse events such as cardiotoxicities. ICI-related myocarditis, though less common, can be fatal in 30% of cases. Clinical manifestations vary but can include chest pain, dyspnea, palpitations, heart failure symptoms, and arrhythmias. Diagnosis involves echocardiography, cardiac MRI, and endomyocardial biopsy. Treatment includes high-dose corticosteroids with potential additional immunosuppressants. Baseline EKG and troponin are recommended before ICI initiation, but routine surveillance is not advised. Subclinical myocarditis is a challenge, with unclear management implications. So let’s dive in and learn about cardiotoxicity of novel immunotherapies with Drs. Giselle Suero (series co-chair), Evelyn Song (episode FIT lead), Daniel Ambinder (CardioNerds co-founder), and Tomas Neilan (faculty expert). Audio editing by CardioNerds Academy Intern, Dr. Maryam Barkhordarian.

This episode is supported by a grant from Pfizer Inc.

This CardioNerds Cardio-Oncology series is a multi-institutional collaboration made possible by contributions of stellar fellow leads and expert faculty from several programs, led by series co-chairs, Dr. Giselle Suero Abreu, Dr. Dinu Balanescu, and Dr. Teodora Donisan.

US Cardiology Review is now the official journal of CardioNerds! Submit your manuscript here.

CardioNerds Cardio-Oncology Page

CardioNerds Episode Page

CardioNerds Academy

Cardionerds Healy Honor RollCardioNerds Journal Club

Subscribe to The Heartbeat Newsletter!

Check out CardioNerds SWAG!

Become a CardioNerds Patron!Pearls and Quotes – Cardiotoxicity of Novel Immunotherapies

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) play a crucial role in current oncology treatment by enhancing T-cell recognition against tumors.

- ICI-related cardiac immune-related adverse events (iRAEs) include myocarditis, heart failure, stress-cardiomyopathy, conduction abnormalities, venous thrombosis, pericardial disease, vasculitis, and atherosclerotic-related events.

- ICI myocarditis can be fatal; thus, prompt recognition and treatment is crucial.

- Management includes cessation of the ICI and treatment with corticosteroids and potentially other immunosuppressants. Close monitoring and collaboration with cardiology and oncology are crucial.

- Rechallenging patients with immunotherapies after developing an iRAE is controversial and requires careful consideration of risks and benefits, typically with the involvement of a multidisciplinary team.

Show notes – Cardiotoxicity of Novel Immunotherapies

What are immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs)?

- ICIs are monoclonal antibodies used to enhance the body’s immune response against cancer cells. Currently, there are four main classes of FDA-approved ICIs: monoclonal antibodies blocking cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4), programed cell death protein-1 (PD-1), lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG3), and programmed cell death ligand-1 (PD-L1).

- ICIs can lead to non-specific activation of the immune system, potentially causing off-target adverse events in various organs, including the heart, leading to myocarditis.

- The mechanisms of cardiac iRAEs are not fully understood, but they are believed to involve T-cell activation against cardiac antigens, which leads to inflammation and tissue damage.

What are the cardiotoxicities related to ICI therapies?

- ICI-related cardiac immune-related adverse events (iRAEs) include myocarditis, heart failure, stress-cardiomyopathy, conduction abnormalities, venous thrombosis, pericardial disease, vasculitis, and atherosclerotic-related events.

- ICI-related myocarditis is considered rare compared to other systemic IRAEs. While the incidence rate of ICI-myocarditis is around 0.7-2.0%, it can be fatal in 30% of cases.

- Clinical manifestations vary but can include chest pain, dyspnea, palpitations, heart failure symptoms, and arrhythmias. Severe cases of ICI myocarditis can present as cardiogenic shock or complete heart block (a fulminant myocarditis picture).

- The timing of adverse events is typically within the first three months of starting immunotherapy, with the majority occurring early on; however, some cases may present after three months.

- Increased clinical suspicion is key for early recognition and prompt diagnosis and treatment.

What is the general approach to the diagnosis of ICI-myocarditis?

- Diagnosis is based on clinical history and presentation, elevated troponin, and imaging findings. Echocardiography (with global longitudinal strain) and cardiac MRI (with T1 and T2 mapping as per the modified Lake Louise Criteria) are key diagnostic tools. If cardiac MRI is not diagnostic but suspicion remains high, an endomyocardial biopsy is the next diagnostic step.

- Baseline cardiac tests, such as ECG and troponin, are important before initiating ICIs in every patient to serve as a reference standard for comparison in case of troponin elevation during therapy. However, routine surveillance of asymptomatic patients on ICIs is not recommended.

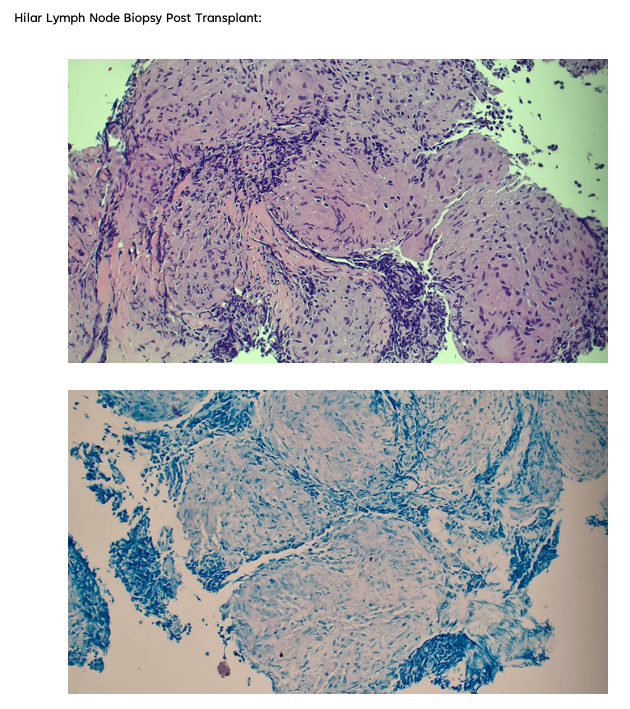

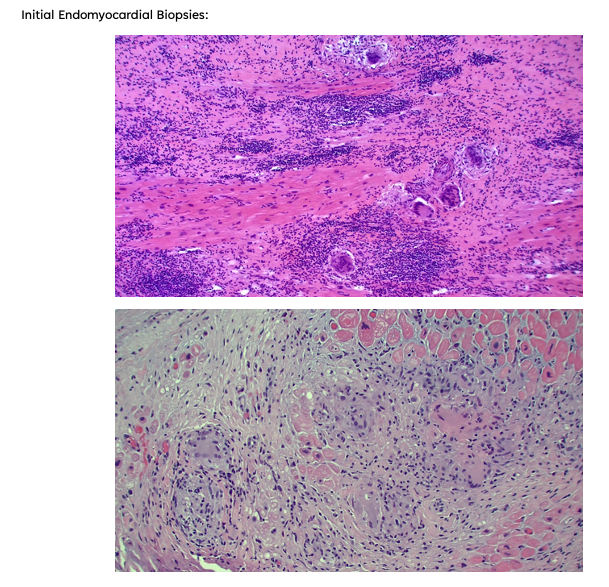

How do endomyocardial biopsy findings for ICI-myocarditis compare to other types of autoimmune-mediated conditions such as transplant rejection?

- ICI-myocarditis is pathologically almost identical to transplant rejection; therefore, a similar grading system used for transplant rejection is applied to ICI-myocarditis to determine the severity and provide guidance on the intensity of immunosuppression.

What are the treatment strategies for ICI-myocarditis?

- In general, all patients with suspected ICI-myocarditis should have their immunotherapy held temporarily until the diagnosis is confirmed. Next, patients should be typically admitted to an inpatient unit with telemetry capabilities, given the risk of progression to complete heart block and cardiogenic shock.

- High-dose corticosteroids are the first-line pharmacological treatment, but the optimal dose varies between guidelines. An approach for severe life-threatening cases based on the NCCN and SITC guideline recommendations is a pulse of high-dose corticosteroids (consider 1000 mg methylprednisolone IV daily for 3–5 days until troponin normalizes) followed by a taper of 1–2 mg/kg methylprednisolone or oral prednisone for 4–6 weeks.

- For patients who do not respond to high-dose corticosteroids, additional immunosuppressive therapies can be considered, including intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), mycophenolate mofetil, anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG), alemtuzumab (monoclonal antibody to CD52), abatacept (CTLA-4 agonist), or plasmapheresis. This is an area where more data is needed to support guidelines for patient treatment. Currently, there are ongoing studies in this area, such as a phase 3 clinical of Abatacept for immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated myocarditis (ATRIUM, NCT053359280)

- High doses of corticosteroids used to treat ICI-associated myocarditis may adversely impact cancer outcomes. Further research is needed to understand the impact of cardiac toxicities and immunosuppressive treatments on cancer outcomes

Can patients be re-treated after an episode of ICI myocarditis?

- Patients who develop ICI-associated adverse events, including myocarditis, may have a second chance and be rechallenged with ICIs after resolution of the adverse event, but this decision should be made carefully considering the risks and benefits.

References – Cardiotoxicity of Novel Immunotherapies

Meet Our Collaborators

International Cardio-Oncology Society ( IC-OS). IC-OS exits to advance cardiovascular care of cancer patients and survivors by promoting collaboration among researchers, educators and clinicians around the world. Learn more at https://ic-os.org/.

22 April 2024, 3:22 am

22 April 2024, 3:22 am - 38 minutes 26 seconds364. Case Report: A Drug’s Adverse Effect Unleashes the Wolf – Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

CardioNerds join Dr. Inbar Raber and Dr. Susan Mcilvaine from the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center for a Fenway game. They discuss the following case: A 72-year-old man presents with two weeks of progressive dyspnea, orthopnea, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and right upper quadrant pain. He has a history of essential thrombocytosis, Barrett’s esophagus, basal cell skin cancer, and hypertension treated with hydralazine. He is found to have bilateral pleural effusions and a pericardial effusion. He undergoes a work-up, including pericardial cytology, which is negative, and blood tests reveal a positive ANA and positive anti-histone antibody. He is diagnosed with drug-induced lupus due to hydralazine and starts treatment with intravenous steroids, resulting in an improvement in his symptoms. Expert commentary is provided by UT Southwestern internal medicine residency program director Dr. Salahuddin (“Dino”) Kazi.

“To study the phenomena of disease without books is to sail an uncharted sea, while to study books without patients is not to go to sea at all.” – Sir William Osler. CardioNerds thank the patients and their loved ones whose stories teach us the Art of Medicine and support our Mission to Democratize Cardiovascular Medicine.

US Cardiology Review is now the official journal of CardioNerds! Submit your manuscript here.

CardioNerds Case Reports Page

CardioNerds Episode Page

CardioNerds Academy

Cardionerds Healy Honor RollCardioNerds Journal Club

Subscribe to The Heartbeat Newsletter!

Check out CardioNerds SWAG!

Become a CardioNerds Patron!Case Media

Pearls – A Drug’s Adverse Effect Unleashes the Wolf

- The differential diagnosis for pericardial effusion includes metabolic, malignant, medication-induced, traumatic, rheumatologic, and infectious etiologies.

- While pericardial cytology can aid in securing a diagnosis of cancer in patients with malignant pericardial effusions, the sensitivity of the test is limited at around 50%.

- Common symptoms of drug-induced lupus include fever, arthralgias, myalgias, rash, and/or serositis.

- Anti-histone antibodies are typically present in drug-induced lupus, while anti-dsDNA antibodies are typically absent (unlike in systemic lupus erythematosus, SLE).

- Hydralazine-induced lupus has a prevalence of 5-10%, with a higher risk for patients on higher doses or longer durations of drug exposure. Onset is usually months to years after drug initiation.

Show Notes – A Drug’s Adverse Effect Unleashes the Wolf

- There is a broad differential diagnosis for pericardial effusion which includes metabolic, malignant, medication-induced, traumatic, rheumatologic, and infectious etiologies. Metabolic etiologies include renal failure and thyroid disease. Certain malignancies are more likely to cause pericardial effusions, including lung cancer, lymphoma, breast cancer, sarcoma, and melanoma. Radiation therapy to treat chest malignancies can also result in a pericardial effusion. Medications can cause pericardial effusion, including immune checkpoint inhibitors, which can cause myocarditis or pericarditis, and medications associated with drug-induced lupus, such as procainamide, hydralazine, phenytoin, minoxidil, or isoniazid. Trauma can cause pericardial effusions, including blunt chest trauma, cardiac surgery, or cardiac catheterization. Rheumatologic etiologies include lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis, sarcoid, and vasculitis. Many different types of infections can cause pericardial effusions, including viruses (e.g., coxsackievirus, echovirus, adenovirus, human immunodeficiency virus, and influenza), bacteria (TB, staphylococcus, streptococcus, and pneumococcus), and fungi. Other must-not-miss etiologies include emergencies like type A aortic dissection and myocardial infarction.

- In a retrospective study of all patients who presented with a hemodynamically significant pericardial effusion and underwent pericardiocentesis, 33% of patients were found to have an underlying malignancy(Ben-Horin et al). Bloody effusion and frank tamponade were significantly more common among patients with malignant effusion, but the overlap was significant, and no epidemiologic or clinical parameter was found useful to differentiate between cancerous and noncancerous effusions. Although this patient’s pericardial fluid cytology was negative, cytology is typically only positive in around 50% of malignant effusions (Ben-Horin et al).

- The risk of drug-induced lupus (DIL) with hydralazine is high, approaching 10% of all treated patients. Another more commonly implicated cardiovascular drug is procainamide, with an incidence of 15-20%. Anti-histone antibodies are typically positive in DIL caused by hydralazine or procainamide, whereas anti-double stranded DNA antibodies are typically absent (in contrast to systemic lupus erythematosus). The most common symptoms of DIL include fever, arthralgias, myalgias, rash, and/or serositis with onset after months to years of drug exposure. If serositis is present, it is more often pleuritis, +/- pericarditis.

- In addition to stopping the offending medication, treatment is extrapolated from the treatment of idiopathic systemic lupus and can include NSAIDs, hydroxychloroquine, and/or systemic steroids, depending on disease severity.

References – A Drug’s Adverse Effect Unleashes the Wolf

- Ben-Horin, Bank, Guetta, & Livneh, A. (2006). Large symptomatic pericardial effusion as the presentation of unrecognized cancer – A study in 173 consecutive patients undergoing pericardiocentesis. Medicine (Baltimore), 85(1), 49–53.

- Borchers, A.T., Keen, C.L. and Gershwin, M.E. (2007), Drug-Induced Lupus. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1108: 166-182.

- Feng, Glockner, J., et al. (2011). Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging Pericardial Late Gadolinium Enhancement and Elevated Inflammatory Markers Can Predict the Reversibility of Constrictive Pericarditis After Antiinflammatory Medical Therapy A Pilot Study. Circulation (New York, N.Y.), 124(17), 1830–1837

14 March 2024, 2:34 am - 43 minutes 1 second363. GLP-1 Agonists: Diving into the Data with Dr. Darren McGuire

Welcome back to the CardioNerds Cardiovascular Prevention Series, where we are continuing our discussion of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists (GLP-1 RAs). This class of medications is becoming a household name, not only for their implications for weight loss but also for their effect on cardiovascular disease. CardioNerds Dr. Ty Sweeney (CardioNerds Academy Faculty Member and incoming Cardiology Fellow at Boston Medical Center), Dr. Rick Ferraro (CardioNerds Academy House Faculty and Cardiology Fellow at Johns Hopkins Hospital), and special guest Dr. Franck Azobou (Cardiology Fellow at UT Southwestern) sat down with Dr. Darren McGuire (Cardiologist at UT Southwestern and Senior Editor of Diabetes and Vascular Disease Research) to discuss important trial data on GLP-1 RAs in patients with heart disease, as well as recent professional society guidelines on their use. Show notes were drafted by Dr. Ty Sweeney. Audio editing was performed by CardioNerds Intern student Dr. Diane Masket.

If you haven’t already, be sure to check out CardioNerds episode #350 where we discuss the basics and mechanism of action of GLP-1 RAs with Dr. Dennis Bruemmer.

This episode was produced in collaboration with the American Society of Preventive Cardiology (ASPC) with independent medical education grant support from Novo Nordisk. See below for continuing medical education credit.

Claim CME for this episode HERE.

US Cardiology Review is now the official journal of CardioNerds! Submit your manuscript here.

CardioNerds Prevention Page

CardioNerds Episode Page

CardioNerds Academy

Cardionerds Healy Honor RollCardioNerds Journal Club

Subscribe to The Heartbeat Newsletter!

Check out CardioNerds SWAG!

Become a CardioNerds Patron!Pearls and Quotes – GLP-1 Agonists: Diving into the Data

- Patients with diabetes and clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) or who are at high risk of ASCVD benefit from treatment with a GLP-1 RA.

- For persons with sufficient ASCVD risk and type 2 diabetes, GLP-1 RAs and SGLT2 inhibitors can, and often should, be used in combination. “Just like we don’t consider ‘and/or’ for the four pillars of guideline-directed medical therapy for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, we shouldn’t parcel out these two therapeutic options…it should be both.”

- Setting expectations with your patients regarding injection practices, side effects, and expected benefits can go a long way toward improving the patient experience with GLP-1 RAs.

- Utilize a multidisciplinary approach when caring for patients on GLP-1 RAs. Build a team with your patient’s primary care provider, endocrinologist, clinical pharmacist, and nurse.

- “This is really a cardiologist issue. These are no longer endocrinology or primary care drugs. We need to be prescribing them ourselves just like we did back in the nineties when we took over the statin prescriptions from the endocrinology domain…we need to lead the way.”

Show notes – GLP-1 Agonists: Diving into the Data

For which patients are GLP-1 RAs recommended to reduce the risk of major cardiac events?

- For patients with type 2 diabetes and ASCVD, starting a GLP-1 RA carries a Class 1, Level of Evidence A recommendation in the most recent ESC and ACC guidelines.

- For patients without diabetes or clinical ASCVD with an estimated 10-year risk of CVD exceeding 10%, consideration of starting a GLP-1 RA carries a Class 2b, Level of Evidence C recommendation to reduce CV risk.

- The STEP-HFpEF trial showed that among patients with obesity and HFpEF, once-weekly semaglutide may be beneficial in terms of weight loss and quality of life.

- The results of the FIGHT and LIVE trials question the utility and safety of liraglutide in treating patients with advanced HFrEF. Of the over 17,000 patients enrolled in the SELECT trial, about 25% had heart failure, of which about one-third had HFrEF. Stay tuned for sub-analyses from that trial for more info!

Can we still prescribe GLP-1 Ras in patients with well-controlled T2DM?

- The recommendation to start GLP-1 RAs for cardiovascular benefit in eligible patients is made irrespective of HbA1C.

- If A1c is very low, or if the patient is experiencing episodes of hypoglycemia, consider backing off background diabetes therapy, especially if they don’t confer CV benefit.

- Note, the recent ESC guidelines recommending SGLT2i and GLP-1RA therapy do so irrespective of background metformin therapy. This is supported by the ADA Standards of Care in Diabetes.

Is there evidence to suggest oral vs injectable GLP-1 RAs with respect to cardiac outcomes?

- The PIONEER-6 trial suggests cardiovascular benefit of oral semaglutide in patients with diabetes compared to placebo; however, the trial was only powered to assess safety.

- The ongoing SOUL trial is examining cardiovascular outcomes among patients being treated with oral semaglutide vs placebo with the primary outcome of time from randomization to the first occurrence of a major adverse CV event. Stay tuned!

- It is crucial that oral semaglutide be taken on an empty stomach, given its unique absorption and pharmacokinetics.

What side effects can patients expect when initiating GLP-1 RAs?

- Nausea is common after starting these medications, but this generally ameliorates after 1-2 weeks of therapy.

- Setting expectations with your patients ahead of time can go a long way to improving adherence.

- We do not have dose-response data to say whether sub-maximal doses of GLP-1 RAs (for example, in patients who do not want or cannot tolerate the full dose) are effective. That said, the SELECT trial suggests the benefits of starting GLP-1 RAs begin early, even at introductory doses. Therefore, if a patient truly cannot tolerate higher doses, it may be reasonable to titrate slowly or hold at a lower dose.

What does the literature say regarding the combined use of SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 RAs?

- Sub-analyses examining the effect of background therapy when patients are randomized to receive the other vs. placebo suggest patients enjoy at least as good, if not better, outcomes from the combination of therapies.

- One of the first planned sub-analyses of SOUL will look at the potential additive effects of oral semaglutide alongside background SGLT2 inhibitor therapy.

References – GLP-1 Agonists: Diving into the Data

- Marx N, Federici M, Schütt K, et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetes: Developed by the task force on the management of cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetes of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European Heart Journal. 2023;44(39):4043-4140. https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/44/39/4043/7238227?login=false

- Virani SS, Newby LK, Arnold SV, et al. 2023 AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Chronic Coronary Disease: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2023;148(9):e9-e119. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001168

- ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 10. Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care. 2022;46(Supplement_1):S158-S190. https://diabetesjournals.org/care/article/46/Supplement_1/S158/148038/10-Cardiovascular-Disease-and-Risk-Management

- Husain M, Birkenfeld AL, Donsmark M, et al. Oral Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;381(9):841-851. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1901118

- McGuire DK, Busui RP, Deanfield J, et al. Effects of oral semaglutide on cardiovascular outcomes in individuals with type 2 diabetes and established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and/or chronic kidney disease: Design and baseline characteristics of SOUL, a randomized trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2023;25(7):1932-1941. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36945734/

- Kosiborod MN, Abildstrøm SZ, Borlaug BA, et al. Semaglutide in Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction and Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(12):1069-1084. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37622681/

- Jorsal A, Kistorp C, Holmager P, et al. Effect of liraglutide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue, on left ventricular function in stable chronic heart failure patients with and without diabetes (LIVE)-a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19(1):69-77. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27790809/

- Margulies KB, Hernandez AF, Redfield MM, et al. Effects of Liraglutide on Clinical Stability Among Patients With Advanced Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;316(5):500-508. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/2540402

12 March 2024, 2:53 am

12 March 2024, 2:53 am - 17 minutes 10 seconds362. Guidelines: 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure – Question #32 with Dr. Harriette Van Spall

The following question refers to Section 13 of the 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure.

The question is asked by Western Michigan University medical student and CardioNerds Intern Shivani Reddy, answered first by Mayo Clinic Cardiology Fellow and CardioNerds Academy Faculty Dr. Dinu Balanescu, and then by expert faculty Dr. Harriette Van Spall.

Dr. Van Spall is an Associate Professor of Medicine, cardiologist, and Director of E-Health at McMaster University. Dr Van Spall is a Canadian Institutes of Health Research-funded clinical trialist and researcher with a focus on heart failure, health services, and health disparities.

The Decipher the Guidelines: 2022 AHA / ACC / HFSA Guideline for The Management of Heart Failure series was developed by the CardioNerds and created in collaboration with the American Heart Association and the Heart Failure Society of America. It was created by 30 trainees spanning college through advanced fellowship under the leadership of CardioNerds Cofounders Dr. Amit Goyal and Dr. Dan Ambinder, with mentorship from Dr. Anu Lala, Dr. Robert Mentz, and Dr. Nancy Sweitzer. We thank Dr. Judy Bezanson and Dr. Elliott Antman for tremendous guidance.

Palliative and supportive care has a role for patients with heart failure only in the end stages of their disease.

TRUE

FALSE

Explanation

The correct answer is False

Palliative care is patient- and family-centered care that optimizes health-related quality of life by anticipating, preventing, and treating suffering and should be integrated into the management of all stages of heart failure throughout the course of illness. The wholistic model of palliative care includes high-quality communication, estimation of prognosis, anticipatory guidance, addressing uncertainty, shared decision-making about medically reasonable treatment options, advance care planning; attention to physical, emotional, spiritual, and psychological distress; relief of suffering; and inclusion of family caregivers in patient care and attention to their needs during bereavement.

As such, for all patients with HF, palliative and supportive care—including high-quality communication, conveyance of prognosis, clarifying goals of care, shared decision-making, symptom management, and caregiver support—should be provided to improve QOL and relieve suffering (Class 1, LOE C-LD).

For conveyance of prognosis, objective risk models can be incorporated along with discussion of uncertainty since patients may overestimate survival and the benefits of specific treatments – “hope for the best, plan for the worst.”

For clarifying goals of care, the exploration of each patient’s values and concerns through shared decision-making is essential in important management decisions such as when to discontinue treatments, when to initiate palliative treatments that may hasten death but provide symptom management, planning the location of death, and the incorporation of home services or hospice.

It is a Class I indication that for patients with HF being considered for, or treated with life-extending therapies, the option for discontinuation should be anticipated and discussed through the continuum of care, including at the time of initiation, and reassessed with changing medical conditions and shifting goals of care (LOE C-LD).

Caregiver support should also be offered to family members even beyond death to help them cope with the grieving process.

A formal palliative care consult is not needed for each patient, but the primary team should exercise the above domains to improve processes of care and patient outcomes.

Specialist palliative care consultation can be useful to improve QOL and relieve suffering for patients with heart failure—particularly those with stage D HF who are being evaluated for advanced therapies, patients requiring inotropic support or temporary mechanical support, patients experiencing uncontrolled symptoms, major medical decisions, or multimorbidity, frailty, and cognitive impairment (Class 2a, LOE B). Studies have been mixed on if the palliative team itself improves quality of life and well-being so these interventions should be tailored to each patient and caregiver.

For patients with HF, execution of advanced directives can be useful to improve documentation of treatment preferences, delivery of patient-centered care, and dying in a preferred place (Class 2a, LOE C-LD).

In patients with advanced HF with expected survival < 6 months, timely referral to hospice can be useful to improve QOL (Class 2a, LOE C-LD)

Main Takeaway

In summary, the core principles of palliative care that include communication, transparency on prognosis, clarification of goals of care, shared decision-making, symptom management, and caregiver support should be integrated into each patient’s treatment plan regardless of the stage of heart failure

Guideline Loc.

Section 13, Figure 15, Table 32

Decipher the Guidelines: 2022 Heart Failure Guidelines Page

CardioNerds Episode Page

CardioNerds Academy

Cardionerds Healy Honor RollCardioNerds Journal Club

Subscribe to The Heartbeat Newsletter!

Check out CardioNerds SWAG!

Become a CardioNerds Patron!10 March 2024, 5:34 pm - 41 minutes 33 seconds361. Case Report: Sore Throat, Fever, and Myocarditis – It’s not always COVID-19! – University of Maryland

CardioNerds cofounder Dr. Dan Ambinder joins Dr. Angie Molina, Dr. Cullen Soares, and Dr. Andrew Lutz from the University of Maryland Medical Center for some beers and history by Fort McHenry. They discuss a case of disseminated haemophilus influenza

presumed fulminant bacterial myocarditis with mixed septic/cardiogenic shock. Expert commentary is provided by Dr. Stanley Liu (Assistant Professor, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine). Episode audio was edited by Dr. Chelsea Amo-Tweneboah.A woman in her twenties with a history of intravenous drug use presented with acute onset fevers and sore throat, subsequently developed respiratory distress and cardiac arrest, and was noted to have epiglottic edema on intubation. She developed shock and multiorgan failure. ECG showed diffuse ST elevations, TTE revealed biventricular dysfunction, and pleural fluid culture grew Haemophilus influenza. Right heart catheterization showed evidence of cardiogenic shock. She improved with supportive care and antibiotics.

“To study the phenomena of disease without books is to sail an uncharted sea, while to study books without patients is not to go to sea at all.” – Sir William Osler. CardioNerds thank the patients and their loved ones whose stories teach us the Art of Medicine and support our Mission to Democratize Cardiovascular Medicine.

US Cardiology Review is now the official journal of CardioNerds! Submit your manuscript here.

CardioNerds Case Reports Page

CardioNerds Episode Page

CardioNerds Academy

Cardionerds Healy Honor RollCardioNerds Journal Club

Subscribe to The Heartbeat Newsletter!

Check out CardioNerds SWAG!

Become a CardioNerds Patron!Pearls – Sore Throat, Fever, and Myocarditis – It’s not always COVID-19

- The post-cardiac arrest ECG provides helpful information for diagnosing the underlying etiology.

- Be aware of diagnostic biases – availability and anchoring biases are particularly common during respiratory viral (such as COVID-19, RSV) surges.

- Consider a broad differential diagnosis in evaluating myocarditis, including non-viral etiologies.

- Right heart catheterization provides crucial information for diagnosis and management of undifferentiated shock.

- When assessing the need for mechanical circulatory support, consider the current hemodynamics, type of support needed, and risks associated with each type.

Show Notes – Sore Throat, Fever, and Myocarditis – It’s not always COVID-19

- ECG findings consistent with pericarditis include diffuse concave-up ST elevations and downsloping T-P segment (Spodick’s sign) as well as PR depression (lead II), and PR elevation (lead aVR). In contrast, regional ST elevations with “reciprocal” ST depressions and/or Q-waves should raise concern for myocardial ischemia as the etiology.

- Biventricular dysfunction and elevated troponin are commonly seen post-cardiac arrest and may be secondary findings. However, an elevation in troponin that is out of proportion to expected demand ischemia, ECG changes (pericarditis, ischemic ST elevations), and cardiogenic shock suggest a primary cardiac etiology for cardiac arrest.

- The differential diagnosis of infectious myopericarditis includes, most commonly, viral infection (respiratory viruses) and, more rarely, bacterial, fungal, or parasitic. Noninfectious myopericarditis may be autoimmune (such as lupus, sarcoidosis, checkpoint inhibitors), toxin-induced (alcohol, cocaine), and medication-induced (anthracyclines and others).

- Right heart catheterization can help diagnose the etiology of undifferentiated shock, including distinguishing between septic and cardiogenic shock, by providing right and left-sided filling pressures, pulmonary and systemic vascular resistance, and cardiac output.

- Mechanical circulatory support (MCS) is indicated for patients in cardiogenic shock with worsening end-organ perfusion despite inotropic and pressor support. MCS includes intra-aortic balloon pump, percutaneous VAD, TandemHeart, and VA-ECMO. The decision to use specific types of MCS should be individualized to each patient with their comorbidities and hemodynamic profile. Shock teams are vital to guide decision-making.

References

- Witting MD, Hu KM, Westreich AA, Tewelde S, Farzad A, Mattu A. Evaluation of Spodick’s Sign and Other Electrocardiographic Findings as Indicators of STEMI and Pericarditis. J Emerg Med. 2020;58(4):562-569. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.01.017

- Ferrero P, Piazza I, Lorini LF, Senni M. Epidemiologic and clinical profiles of bacterial myocarditis. Report of two cases and data from a pooled analysis. Indian Heart J. 2020;72(2):82-92. doi:10.1016/j.ihj.2020.04.005

- Pollack A, Kontorovich AR, Fuster V, Dec GW. Viral myocarditis–diagnosis, treatment options, and current controversies. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12(11):670-680. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2015.108

- Hsu S, Fang JC, Borlaug BA. Hemodynamics for the Heart Failure Clinician: A State-of-the-Art Review. J Card Fail. 2022;28(1):133-148. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2021.07.012

- Korabathina R., Heffernan K.S., Paruchuri V., Patel A.R., Mudd J.O., Prutkin J.M., et al: The pulmonary artery pulsatility index identifies severe right ventricular dysfunction in acute inferior myocardial infarction. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2012; 80: pp. 593-600. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21954053/

- Drazner MH, Velez-Martinez M, Ayers CR, et al. Relationship of right- to left-sided ventricular filling pressures in advanced heart failure: insights from the ESCAPE trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(2):264-270. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.000204

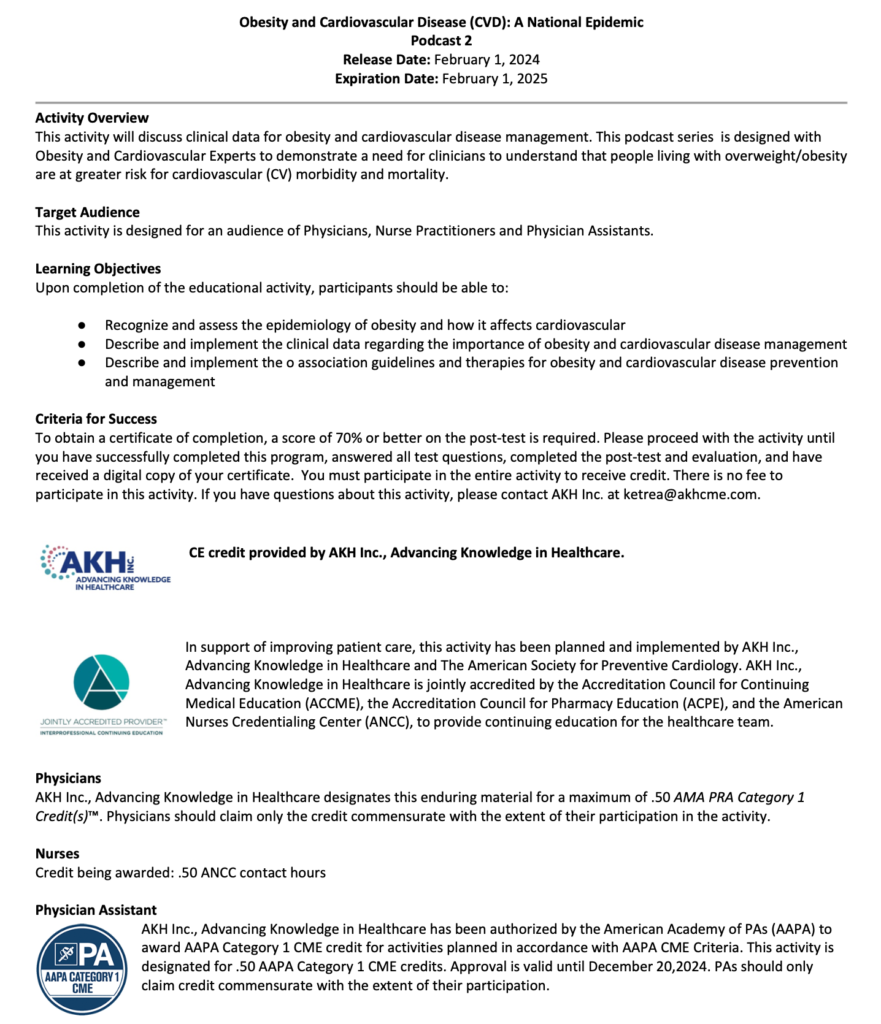

5 March 2024, 3:08 am - 360. Obesity: Lifestyle & Pharmacologic Management of Obesity with Dr. Ambarish Pandey

CardioNerds Dr. Rick Ferraro (CardioNerds Academy House Faculty and Cardiology Fellow at JHH), Dr. Gurleen Kaur (Director of the CardioNerds Internship and Internal Medicine resident at BWH), and Dr. Alli Bigeh (Cardiology Fellow at the Ohio State) as they discuss the growing obesity epidemic and how it relates to cardiovascular disease with Dr. Ambarish Pandey (Cardiologist at UT Southwestern Medical Center). Show notes were drafted by Dr. Alli Bigeh. CardioNerds Academy Intern and student Dr. Shivani Reddy performed audio editing.

Obesity is an important modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease, and it is on the rise! Here, we discuss how to identify patients with obesity and develop an approach to address current lifestyle recommendations. We also discuss the spectrum of pharmacologic treatment options available, management strategies, and some therapy options that are on the horizon.

This episode was produced in collaboration with the American Society of Preventive Cardiology (ASPC) with independent medical education grant support from Novo Nordisk. See below for continuing medical education credit.

Claim CME for this episode HERE.

US Cardiology Review is now the official journal of CardioNerds! Submit your manuscript here.

CardioNerds Prevention Page

CardioNerds Episode Page

CardioNerds Academy

Cardionerds Healy Honor RollCardioNerds Journal Club

Subscribe to The Heartbeat Newsletter!

Check out CardioNerds SWAG!

Become a CardioNerds Patron!Pearls and Quotes – Lifestyle & Pharmacologic Management of Obesity

- Identify obese patients not just using BMI, but also using anthropometric measurements such as waist circumference (central adiposity).

- Lifestyle modifications are our first line of defense against obesity! Current recommendations emphasize caloric restriction of at least 500kcal/day, plant-based and Mediterranean diets, and getting at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity weekly exercise.

- Dive into the root cause of eating and lifestyle behaviors. It is crucial to address adverse social determinants of health with patients to identify the driving behaviors, particularly among those individuals of low socioeconomic status.

- Newer weight loss agents are most effective at achieving and maintaining substantial weight loss, in particular Semaglutide (GLP-1) and Tirzepatide (GLP-1/GIP). Initiate at a low dose and titrate up slowly.

- Obesity is a risk factor and potential driver for HFpEF. Targeted treatment options for obese patients with HFpEF include SGLT-2 inhibitors and semaglutide, which recently showed improvement in quality of life and exercise capacity in the STEP-HFpEF trial.

Show notes – Lifestyle & Pharmacologic Management of Obesity

How do we identify and define obesity?

- The traditional definition of obesity is based on body mass index (BMI), defined as BMI greater than or equal to 30.0 kg/m2 (weight in kg/height in meters).

- Recognize that BMI may not tell the whole story. A limitation of BMI is it does not reflect differences in body composition and distribution of fat.

- Certain patients may not meet the BMI cutoff for obesity but have elevated cardiovascular risk based on increased central adiposity, specifically those that are categorized as overweight.

- The devil lies in the details of anthropometric parameters. Include waist circumference measurements as part of an obesity assessment of visceral adiposity.

- A waist circumference greater than 40 inches for men and greater than 35 inches for women is considered elevated.

What are some current lifestyle recommendations for obese patients?

- Lifestyle recommendations are the first line of defense against obesity.

- Current ACC/AHA guidelines suggest a target of reducing caloric intake by 500 kcal per day. For patients with severe obesity, this number may be higher.

- Emphasis on hypocaloric plant-based and Mediterranean diets

- Reduce total carbohydrate intake to 50-130 grams per day.

- Focus on a low-fat diet with less than 30% of total energy coming from fat with a high-protein diet to maintain lean mass and promote satiety.

- The overarching theme of prevailing lifestyle recommendations is incorporating whole grains, vegetables, fruit, nuts, and fiber-rich foods while minimizing saturated fats, salt, and sugar intake.

- ACC/AHA recommendations include 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week.

What are some tips for addressing lifestyle modifications with patients?

- Tailor the approach to each individual patient. Get to the root cause and identify barriers to addressing the behaviors.

- Consider getting a psychosocial assessment and focus on behavior modification strategies. Eating behaviors can be associated with other behavioral disorders.

- Patients with severe obesity have a higher risk of adverse cardiovascular events. A risk-based approach for these patients mandates a greater emphasis on weight reduction and caloric restriction.

- Consider access to nutrient-dense food, socioeconomic status, cost of healthy foods, access to exercise resources, and safety of neighborhoods when making recommendations.

What are the current pharmacologic options for weight loss? Which are the most effective?

- Consider pharmacological agents once lifestyle modifications and social determinants of health have been addressed. We should not get hung up on lifestyle modifications and fail to progress to using pharmacotherapies or surgical therapies in patients with morbid obesity or cardiovascular disease.

- Pharmacological therapy can be considered in patients with BMI >30 or BMI >27 with comorbidities.

- There are a variety of agents such as Orlistat, Phentermine/Topiramate, Bupropion/Naltrexone, GLP-1 receptor agonists (Liraglutide, Semaglutide) and Tirzepatide (GLP-1/GIP).

- Tirzepatide has the highest amount of reported weight loss, with patients achieving 23% weight loss or up to 50 pounds of weight loss based on the latest SURMOUNT trial. Semaglutide can achieve 16% weight loss based on trial data. The remaining agents have reported weight loss between 6-10%.

- Bariatric surgery should also be considered, especially in patients with severe obesity (BMI >40).

Compare and contrast the GLP-1 agents, specifically semaglutide and liraglutide.

- GLP-1 receptor agonists activate GLP-1 receptors in the pancreas, which increases insulin release, slows gastric emptying, and reduces appetite.

- Semaglutide has a greater weight reduction of up to 16% total weight loss compared to 6% for liraglutide.

- There have been higher reported adverse effects with liraglutide as well. In the STEP-8 trial, the proportion of participants discontinuing treatment for any reason was 13.5% with semaglutide versus 27.6% with liraglutide. Gastrointestinal adverse events were the most common and reported by 84.1% with semaglutide and 82.7% with liraglutide.

- The SELECT trial in patients with preexisting cardiovascular disease and overweight or obesity but without diabetes, weekly subcutaneous semaglutide at a dose of 2.4 mg reduced the incidence of death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke by approximately 20%. Liraglutide has been shown to reduce cardiovascular outcomes in patients with established cardiovascular disease but only in patients with diabetes thus far.

What other newer agents are on the horizon for treatment of obesity?

- An oral formulation of semaglutide 50mg is currently being tested, with phase 3 results showing up to 15% weight reduction in participants.

- Retatrutide is a new triple-hormone-receptor agonist (an agonist of the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide [GIP], glucagon-like peptide 1, and glucagon receptors). Phase 2 trial was recently published, reporting up to 25% weight loss in patients.

Discuss some strategies to mitigate the GI side effects when using GLP-1 receptor agonists.

- Most importantly- keep a close eye on patient’s symptoms and prepare them for potential side effects along with the mechanism through which they work (i.e., inducing early satiety).

- Expect some degree of gastrointestinal discomfort so patients know what to expect. Side effects often dissipate with continued use of the medication. This can help minimize discontinuation.

- Counsel on diet and nutrition. Patients should eat small food portions for better tolerability, given the effect of the medication to slow gastric emptying.

- Providers should focus on starting at a low dose and titrating up slowly.

- If side effects become intolerable, providers can consider using the last tolerated dose or switching medication classes (i.e. Tirzepatide).

References – Lifestyle & Pharmacologic Management of Obesity

- Chakhtoura M, Haber R, Malak G, Caline R, Raya T, Mantzoros CS. Pharmacotherapy of obesity: an update on the available medications and drugs under investigation. Pharmacotherapy of obesity: an update on the available medications and drugs under investigation. 2023;58:101882-101882. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.101882

- Després JP, Carpentier AC, Tchernof A, Neeland IJ, Poirier P. Management of Obesity in Cardiovascular Practice. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2021;78(5):513-531. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2021.05.035

- Dominguez LJ, Veronese N, Di Bella G, et al. Mediterranean diet in the management and prevention of obesity. Experimental Gerontology. 2023;174:112121. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2023.112121

- Jastreboff AM, Aronne LJ, Ahmad NN, et al. Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity. New England Journal of Medicine. 2022;387(3). doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2206038

- Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS Guideline for the Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. Circulation. 2013;129(25 suppl 2):S102-S138. doi:https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee

- Kosiborod M, Abildstrøm SZ, Borlaug BA, et al. Semaglutide in Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction and Obesity. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2023;389(12). doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2306963

- Lincoff MA, Brown‐Frandsen K, Colhoun HM, et al. Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Obesity without Diabetes. The New England Journal of Medicine. Published online November 11, 2023. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2307563

- Rubino DM, Greenway FL, Khalid U, et al. Effect of Weekly Subcutaneous Semaglutide vs Daily Liraglutide on Body Weight in Adults With Overweight or Obesity Without Diabetes. JAMA. 2022;327(2):138. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.23619

19 February 2024, 5:17 pm - 59 minutes 23 seconds359. Case Report: Fee-Fi-Fo-Fum: An Unusual Case of Rapidly Progressive Heart Failure – Georgetown University

CardioNerds join Dr. Ethan Fraser and Dr. Austin Culver from the MedStar Georgetown University Hospital internal medicine and cardiology programs in our nation’s capital. They discuss the following case involving an unusual case of rapidly progressive heart failure. Episode audio was edited by CardioNerds Academy Intern and student Dr. Pacey Wetstein. Expert commentary was provided by advanced heart failure cardiologist Dr. Richa Gupta.

A 55-year-old male comes to the clinic (and eventually into the hospital) for what appears to be a straightforward decompensation of his underlying cardiac disease. However, things aren’t as simple as they might appear. In this episode, we will discuss the outpatient workup for non-ischemic cardiomyopathy and discuss the clinical indicators that we as clinicians should be aware of in these sick patients. Furthermore, we will discuss the differential for NICM, the management of patients with this rare disease, and how this disease can mimic other cardiomyopathies.

“To study the phenomena of disease without books is to sail an uncharted sea, while to study books without patients is not to go to sea at all.” – Sir William Osler. CardioNerds thank the patients and their loved ones whose stories teach us the Art of Medicine and support our Mission to Democratize Cardiovascular Medicine.

US Cardiology Review is now the official journal of CardioNerds! Submit your manuscript here.

CardioNerds Case Reports Page

CardioNerds Episode Page

CardioNerds Academy

Cardionerds Healy Honor RollCardioNerds Journal Club

Subscribe to The Heartbeat Newsletter!

Check out CardioNerds SWAG!

Become a CardioNerds Patron!Case Media – Rapidly Progressive Heart Failure

Pearls – Rapidly Progressive Heart Failure

- The non-ischemic cardiomyopathy workup should incorporate targeted multimodal imaging, thorough history taking, broad laboratory testing, genetic testing if suspicion exists for a hereditary cause, and a deep understanding of which populations are at higher risk for certain disease states.

- Key Point: Always challenge and question the etiology of an unknown cardiomyopathy – do not assume an etiology based on history/patient story alone.

- Unexplained conduction disease in either a young or middle-aged individual in the setting of a known cardiomyopathy should raise suspicion for an infiltrative cardiomyopathy and set off a referral to an advanced heart failure program.

- Key Point: Consider early/more aggressive imaging for these patients and early electrophysiology referral for primary/secondary prevention.

- Giant Cell Myocarditis is a rapidly progressive cardiomyopathy characterized by high mortality (70% in the first year), conduction disease, and classically presents in young/middle-aged men.

- Key Point: If you have a younger male with rapidly progressive cardiomyopathy (anywhere as quickly as 1-2 months, weeks in some cases) and conduction disease, consider early endomyocardial biopsy, even before other advanced imaging modalities.

- The Diagnosis of Giant Cell Myocarditis is time-sensitive – early identification and treatment are essential to survival.

- Key Point: The median timeframe from the time the disease is diagnosed to the time of death is approximately 6 months. 90% of patients are either deceased by the end of 1 year or have received a heart transplant.

- The treatment of Giant Cell Myocarditis is still governed largely by expert opinion, but the key components include high-dose steroids and cyclosporine, largely as a bridge to transplantation or advanced heart failure therapies.

- Key Point: Multi-disciplinary care is essential in delivering excellent care in the diagnostic/pre-transplant period, including involvement by cardiology, cardiac surgery, radiology, critical care, allergy/immunology, case management, advanced heart failure, and shock teams if necessary.

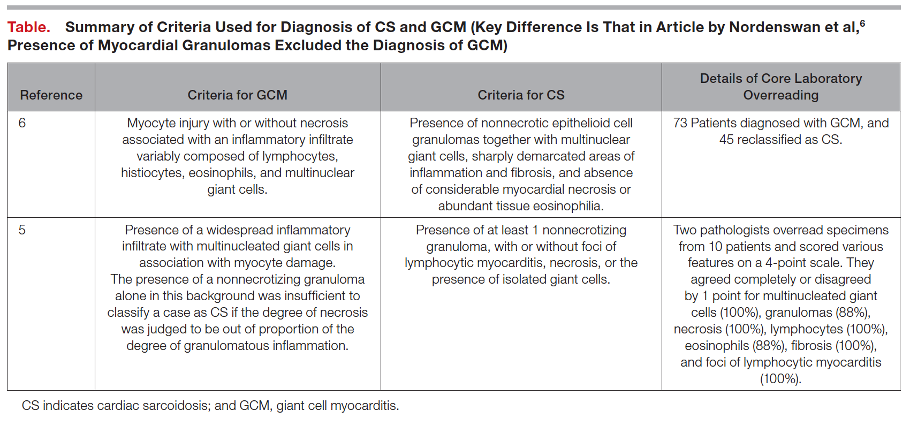

- There remains significant clinical overlap between Giant Cell Myocarditis and sarcoidosis, making managing equivocal cases challenging.

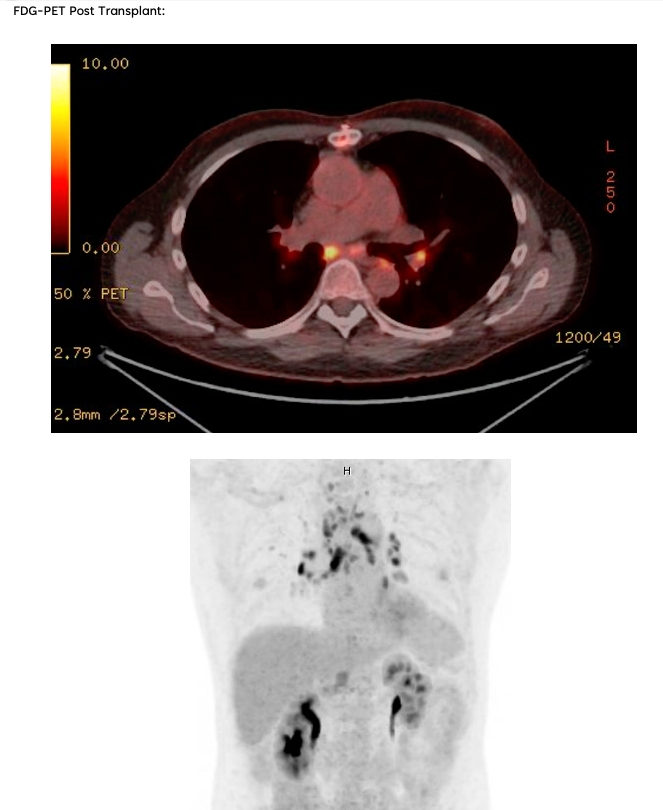

- Key Point: Consider early FDG-PET imaging in equivocal cases, as management during the pre-transplant period and evaluation of transplant candidacy can vary drastically between the two.

Show Notes – Rapidly Progressive Heart Failure

1. What is Giant Cell Myocarditis?

Giant cell myocarditis is a rare and rapidly progressive cause of heart failure due to T-cell lymphocyte mediated myocardial inflammation. The pathogenesis of GCM is incompletely understood – histologically, there is infiltration of the myocardium by T-lymphocytes and macrophages, and there is typically evidence of upregulation of IL-17 and TNF-a. Classically, the disease state is associated with electrical (e.g., ventricular tachycardia, high-grade AV block) and hemodynamic instability – all of which typically progresses rapidly over a period of weeks to months. This male-predominant disease tends to occur in young and middle-aged patients – with a mean age between 42 and 60 based on several registries. While a rare disease, a high index of suspicion is necessary when patients present with rapidly progressive or fulminant heart failure, as a missed diagnosis of giant cell myocarditis is invariably fatal. Early and rapid identification of this uniquely high-risk group of heart failure patients and prompt initiation of therapy targeted towards the underlying autoimmune process, as well as management at a center with advanced heart failure and cardiovascular ICU support, is necessary.

2. How is Giant Cell Myocarditis Diagnosed?

Establishing a diagnosis requires an endomyocardial biopsy (EMB), although EMB has imperfect sensitivity for GCM. Cardiac biomarkers and imaging serve an adjunct role in diagnosis; TTE findings can be variable, with either normal or dilated LV cavity size and increased wall thickness, which may be related to acute edema and inflammation. Worse LVEF on presentation has been shown to correlate with shorter transplant-free survival time. Troponin levels may be elevated, but case series have shown a lack of correlation between prognosis and troponin elevation in GCM, and importantly, in some cases, troponin values have been negative in patients later found to have GCM by biopsy. Advanced imaging is not always practical as these patients are often hemodynamically unstable, but CMR can demonstrate findings typical of myocarditis (i.e. the 2018 Lake Louise criteria).

3. What is the treatment for Giant Cell Myocarditis, and what are the future steps for disease management?

Cyclosporine-based combination immunosuppressive therapy, in addition to standard heart failure guideline-directed medical and procedural therapy and management of arrhythmias, can improve outcomes in these patients. Typical regimens include cyclosporine, high-dose steroids as the mainstay, and azathioprine or alemtuzumab (an anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody) as adjunctive agents. Patients are often co-managed by advanced heart failure, cardiac intensivists, and rheumatology. As the disease progresses, patients often develop sustained or symptomatic ventricular tachycardia, conduction abnormalities refractory HF with a dilated LV phenotype and many require mechanical circulatory support and/or cardiac transplantation.

GCM can remit and relapse, sometimes many years after initial diagnosis; an advanced heart failure team should follow these patients and should continue some immunosuppression (usually a calcineurin inhibitor) for at least 2 years. Overall, our understanding of the mechanism and management of GCM continues to evolve; high-grade evidence such as randomized controlled trials are extremely difficult to perform due to the rarity and high acuity of these presentations, therefore enrolling these patients in shared multicenter registries where able is essential to shrinking our knowledge gaps of this rare disease state.

4. What else should one consider in presumed cases of Giant Cell Myocarditis?

There exists a significant clinical overlap between Giant Cell Myocarditis and Cardiac Sarcoidosis, so much so that some argue the two diseases exist on opposite ends of one disease spectrum. Both notably present with significant arrhythmia burden and advanced heart failure symptoms, although they are both treated quite differently and present with different time courses (mean time to onset of symptoms 0.3 months for GCM, 7 months for CS). Furthermore, data from Nordenswan et al. from Finland reveals that the diagnosis of GCM on histology was recategorized to CS in 62% of their studies reviewed upon secondary pathology review. To this end, it is important that clinicians consider further advanced imaging modalities (i.e., FDG-PET) in equivocal cases and consider expert pathology evaluation of endomyocardial biopsy samples as proper escalation of care and rapid identification can prevent significant treatment delays.

References – Rapidly Progressive Heart Failure

- Amancherla, Kaushik, Juan Qin, Yu Wang, Margaret L. Axelrod, Justin M. Balko, Kelly H. Schlendorf, Robert D. Hoffman, Yaomin Xu, JoAnn Lindenfeld, and Javid Moslehi. “RNA-Sequencing Reveals a Distinct Transcriptomic Signature for Giant Cell Myocarditis and Identifies Novel Druggable Targets.” Circulation Research 129, no. 3 (2021): 451–53. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.319317.

- Bang, Vigyan, Sarju Ganatra, Sachin P. Shah, Sourbha S. Dani, Tomas G. Neilan, Paaladinesh Thavendiranathan, Frederic S. Resnic, et al. “Management of Patients With Giant Cell Myocarditis.” Journal of the American College of Cardiology 77, no. 8 (2021): 1122–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.074.

- Birnie, David H., Vidhya Nair, and John P. Veinot. “Cardiac Sarcoidosis and Giant Cell Myocarditis: Actually, 2 Ends of the Same Disease?” Journal of the American Heart Association 10, no. 6 (2021): e020542. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.121.020542.

- Bobbio, Emanuele, Marie Björkenstam, Bright I. Nwaru, Francesco Giallauria, Eva Hessman, Niklas Bergh, Christian L. Polte, Jukka Lehtonen, Kristjan Karason, and Entela Bollano. “Short- and Long-Term Outcomes after Heart Transplantation in Cardiac Sarcoidosis and Giant-Cell Myocarditis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Clinical Research in Cardiology 111, no. 2 (February 1, 2022): 125–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-021-01920-0.

- Brailovsky, Yevgeniy, Amirali Masoumi, Rachel Bijou, Estefania Oliveros, Gabriel Sayer, Koji Takeda, and Nir Uriel. “Fulminant Giant Cell Myocarditis Requiring Bridge With Mechanical Circulatory Support to Heart Transplantation.” JACC: Case Reports 4, no. 5 (2022): 265–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccas.2021.11.013.

- Cooper, Leslie T., Gerald J. Berry, and Ralph Shabetai. “Idiopathic Giant-Cell Myocarditis — Natural History and Treatment.” New England Journal of Medicine 336, no. 26 (1997): 1860–66. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199706263362603.

- Ekström K, Lehtonen J, Kandolin R, Räisänen-Sokolowski A, Salmenkivi K, Kupari M. Incidence, Risk Factors, and Outcome of Life-Threatening Ventricular Arrhythmias in Giant Cell Myocarditis. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology. 2016;9(12):e004559. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.116.004559

- Fallon, J. M., A. M. Parker, S. P. Dunn, and J. L. W. Kennedy. “A Giant Mystery in Giant Cell Myocarditis: Navigating Diagnosis, Immunosuppression, and Mechanical Circulatory Support.” ESC Heart Fail 7, no. 1 (February 2020): 315–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/ehf2.12564.

- Ghaly, Medhat, Danise Schiliro, and Jadwiga Stepczynski. “Giant Cell Myocarditis: A Time Sensitive Distant Diagnosis.” Cureus 12, no. 1 (2020): e6712–e6712. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.6712.

- Gilotra NA, Minkove N, Bennett MK, et al. Lack of Relationship Between Serum Cardiac Troponin I Level and Giant Cell Myocarditis Diagnosis and Outcomes. Journal of Cardiac Failure. 2016;22(7):583-585. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2015.12.022

- Heymans S, Eriksson U, Lehtonen J, Cooper LT. The Quest for New Approaches in Myocarditis and Inflammatory Cardiomyopathy. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2016;68(21):2348-2364. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.09.937

- Kandolin, Riina, Jukka Lehtonen, Kaisa Salmenkivi, Anne Räisänen-Sokolowski, Jyri Lommi, and Markku Kupari. “Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcome of Giant-Cell Myocarditis in the Era of Combined Immunosuppression.” Circulation: Heart Failure 6, no. 1 (2013): 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.969261.

- Kociol, Robb D., Leslie T. Cooper, James C. Fang, Javid J. Moslehi, Peter S. Pang, Marwa A. Sabe, Ravi V. Shah, Daniel B. Sims, Gaetano Thiene, and Orly Vardeny. “Recognition and Initial Management of Fulminant Myocarditis.” Circulation 141, no. 6 (2020): e69–92. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000745.

- Kondo, Toru, Takahiro Okumura, Naoki Shibata, Takahiro Imaizumi, Kaoru Dohi, Hideo Izawa, Nobuyuki Ohte, Tetsuya Amano, and Toyoaki Murohara. “Differences in Prognosis and Cardiac Function According to Required Percutaneous Mechanical Circulatory Support and Histological Findings in Patients With Fulminant Myocarditis: Insights From the CHANGE PUMP 2 Study.” Journal of the American Heart Association 11, no. 4 (2022): e023719. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.121.023719.

- Nordenswan, Hanna‐Kaisa, Jukka Lehtonen, Kaj Ekström, Anne Räisänen‐Sokolowski, Mikko I. Mäyränpää, Tapani Vihinen, Heikki Miettinen, et al. “Manifestations and Outcome of Cardiac Sarcoidosis and Idiopathic Giant Cell Myocarditis by 25‐Year Nationwide Cohorts.” Journal of the American Heart Association 10, no. 6 (2021): e019415. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.120.019415.

- Paitazoglou, Christina, Martin W. Bergmann, Katharina Tiemann, Andrea Wiese, Ulrich Schäfer, Arne Schwarz, Ingo Eitel, and Moritz Montenbruck. “Atrial Giant Cell Myocarditis as a Cause of Heart Failure.” JACC: Case Reports 4, no. 1 (2022): 66–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccas.2021.11.007.

- PALMER, HARLEY P., and ISAAC E. MICHAEL. “Giant-Cell Myocarditis With Multiple Organ Involvement.” Archives of Internal Medicine 116, no. 3 (1965): 444–47. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1965.03870030124022.

- Polte, Christian L., Entela Bollano, Anders Oldfors, Anna Dudás, Kerstin M. Lagerstrand, Jakob Himmelman, Emanuele Bobbio, Kristjan Karason, Martijn van Essen, and Niklas Bergh. “Somatostatin Receptor Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography in Giant Cell Myocarditis: A Promising Approach to Molecular Myocardial Inflammation Imaging.” Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging 15, no. 1 (2022): e013551. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.121.013551.

- Sujino, Yasumori, Fumiko Kimura, Jun Tanno, Shintaro Nakano, Eriko Yamaguchi, Michio Shimizu, Nanami Okano, et al. “Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Giant Cell Myocarditis.” Circulation 129, no. 17 (2014): e467–69. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005059.

- Xu, J., and E. G. Brooks. “Giant Cell Myocarditis: A Brief Review.” Arch Pathol Lab Med 140, no. 12 (December 2016): 1429–34. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2016-0068-RS.

- Yang, S., X. Chen, J. Li, Y. Sun, J. Song, H. Wang, and S. Zhao. “Late Gadolinium Enhancement Characteristics in Giant Cell Myocarditis.” ESC Heart Fail 8, no. 3 (June 2021): 2320–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/ehf2.13276.

12 February 2024, 5:14 am - The non-ischemic cardiomyopathy workup should incorporate targeted multimodal imaging, thorough history taking, broad laboratory testing, genetic testing if suspicion exists for a hereditary cause, and a deep understanding of which populations are at higher risk for certain disease states.

- 12 minutes 5 seconds358. Guidelines: 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure – Question #31 with Dr. Javed Butler

The following question refers to Section 9.5 of the 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure.

The question is asked by Keck School of Medicine USC medical student & former CardioNerds Intern Hirsh Elhence, answered first by Vanderbilt Cardiology Fellow and CardioNerds Academy Faculty Dr. Breana Hansen, and then by expert faculty Dr. Javed Butler.

Dr. Butler is an advanced heart failure and transplant cardiologist, President of the Baylor Scott and White Research Institute, Senior Vice President for the Baylor Scott and White Health, and Distinguished Professor of Medicine at the University of Mississippi

The Decipher the Guidelines: 2022 AHA / ACC / HFSA Guideline for The Management of Heart Failure series was developed by the CardioNerds and created in collaboration with the American Heart Association and the Heart Failure Society of America. It was created by 30 trainees spanning college through advanced fellowship under the leadership of CardioNerds Cofounders Dr. Amit Goyal and Dr. Dan Ambinder, with mentorship from Dr. Anu Lala, Dr. Robert Mentz, and Dr. Nancy Sweitzer. We thank Dr. Judy Bezanson and Dr. Elliott Antman for tremendous guidance.

Mrs. Hart is a 70-year-old woman who was admitted to the CICU two days ago for signs and symptoms consistent with cardiogenic shock. Since her admission, she has been on maximal diuretics, requiring greater doses of intravenous dobutamine. Unfortunately, her liver and renal function continue to worsen, and urine output is decreasing. A right heart catheterization reveals elevated biventricular filling pressures with a cardiac index of 1.7 L/min/m2 by the Fick method.

What is the next best step?

A

Continue current measures and monitor for improvement

B

Switch from dobutamine to norepinephrine

C

Place an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP)

D

Resume guideline directed medical therapy

Explanation

The Correct answer is C – Place an intra-aortic balloon pump.

This patient is between the SCAI Shock Stages C and D with elevated venous pressures, decreased urine output, and worsening signs of hypoperfusion. She has been started on appropriate therapies, including diuresis and inotropic support. The relevant Class 2a recommendation is that in patients with cardiogenic shock, temporary MCS is reasonable when end-organ function cannot be maintained by pharmacologic means to support cardiac function (LOE B-NR). Thus, the next best step is a form of temporary MCS. IABP is appropriate to help increase coronary perfusion and offload the left ventricle. In fact, for patients who are not rapidly responding to initial shock measures, triage to centers that can provide temporary MCS may be considered to optimize management (Class 2b, LOE C-LD).

The guidelines further state that in patients presenting with cardiogenic shock, placement of a pulmonary arterial line may be considered to define hemodynamic subsets and appropriate management strategies (Class 2B, LOE B-NR). And so, if time allows escalation to MCS should be guided by invasively obtained hemodynamic data via PA catheterization. Several observational experiences have associated PA catheterization use with improved outcomes, particularly in conjunction with short-term MCS. Additionally, PA catheterization is useful when there is diagnostic uncertainty as to the cause of hypotension or end-organ dysfunction, particularly when the patient in shock is not responding to empiric initial measures, such as in this patient.

There are additional appropriate measures at this time that are more institution-dependent. An institutional shock team would be very helpful here as they often comprise multidisciplinary teams of heart failure and critical care specialists, interventional cardiologists, surgeons, and palliative care specialists. As such, there is a Class 2a recommendation that in patients with cardiogenic shock, management by a multidisciplinary team experienced in shock is reasonable (LOE B-NR). Most documented experiences have suggested outcomes improve after shock teams are instituted. For instance, in one such experience, using a shock team was associated with improved 30-day all-cause mortality (HR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.41–0.93) and reduced in-hospital mortality (61.0% vs. 47.9%; P=0.041).

Choice A – Continue current measures and monitor for improvement – is incorrect. This patient has been deteriorating on current measures since admission and is at higher risk for SCAI Shock Stage E – extremis, refractory hypotension/hypoperfusion, and cardiac arrest and, therefore requires escalation of therapy

Choice B- Switch from dobutamine to norepinephrine – is incorrect. The Class 1 LOE B-NR recommendation is that in patients with cardiogenic shock, intravenous inotropic support should be used to maintain systemic perfusion and maintain end-organ performance. Dobutamine is a more potent inotropic agent than norepinephrine. Stopping dobutamine in the setting of her low cardiac index would be incorrect.

Choice D – Resume guideline-directed medical therapy – is incorrect. This patient’s shock is getting worse. The Class 1 LOE B-NR recommendation is that in patients with HFrEF, GDMT should be initiated during hospitalization after clinical stability is achieved. Restarting medications now would be premature.

Main Takeaway

In patients with cardiogenic shock, temporary MCS is reasonable when end-organ function cannot be maintained by pharmacologic means to support cardiac function.

Guideline Loc.

Section 9.5

Decipher the Guidelines: 2022 Heart Failure Guidelines Page

CardioNerds Episode Page

CardioNerds Academy

Cardionerds Healy Honor RollCardioNerds Journal Club

Subscribe to The Heartbeat Newsletter!

Check out CardioNerds SWAG!