Happiness Matters Podcast

Christine Carter and Rona Renner

We often hear parents say, “I just want my children to be happy,” but they also admit that it’s confusing to figure out how to raise happy children—and be happy themselves—on a daily basis. How can we create a home environment where happiness is important for everyone in the family—and limit setting, discipline, and respect are all a part of the equation? Join Dr. Christine Carter and Nurse Rona Renner for conversations from the heart about the science and best practices related to raising happy children. Each week we'll release a new podcast about 10 minutes on Thursday.

- How Talking About Abortion Can Help Opposing Sides

The Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade has split the country into joyous supporters and furious dissenters. Emotions are running high, and some protests have turned violent. Yet research shows that people on either side of the abortion rights issue can bridge their divide if they speak directly and respectfully with one another.

In July 2022, former leaders of prominent abortion-rights and anti-abortion advocacy organizations in Massachusetts gathered to discuss a new documentary film series about conversations they had regularly from 1995 to 2001. The warm friendships that they developed across their deep differences on abortion persist today, decades after their first meeting.

Nicki Gamble, the former president and CEO of Planned Parenthood League of Massachusetts, said during the panel that the opportunity to engage with anti-abortion activists “changed my life.”

Others agreed.

“The facilitators made us really listen,” said Madeline McComish, former president of Massachusetts Citizens for Life. “Most of the time the pro-choice women had said something different than what we thought.”

My research on talks between abortion-rights and anti-abortion advocates found that respectful conversation produces numerous positive outcomes. It helps people listen more deeply and forge personal connections, which can reduce negative stereotypes and foster respect and empathy. In Boston, this translated to a lessening of inflammatory public language.

It can also lead people on opposite sides of an issue to evolve their views and develop more nuanced, complex perspectives.

De-escalating violence

The Abortion Dialogues, as they are known, were launched in Boston in response to lethal shootings in 1994 by an anti–abortion rights gunman at two local abortion clinics.

At that time, the country was deeply polarized about abortion, rocked by violent protests and murders of prominent doctors who provided abortions.

Six women activists for and against abortion rights started confidential talks in Boston in 1995, hoping to de-escalate the violence.

They soon discovered that their moral worldviews presented two irreconcilable philosophies about how to live in the world.

The three participants on the “pro-life,” side, as they chose to call themselves, are all observant Catholics from Boston. They made life choices based on a worldview that there is one truth, guided by their faith, about moral rights and wrongs.

In contrast, the women on the “pro-choice” side, as they referred to themselves, said that they recognized a diversity of personal beliefs and weighed many circumstances in making life choices.

“The pro-choice side does not believe there are moral absolutes,” explained one “pro-life” leader who participated in the talks in a confidential research interview in 2008. “The pro-life participants would force others to conduct their lives according to the ‘one’ truth that they believe,” countered a “pro-choice” activist who also engaged in the talks.

Despite this irreconcilable difference, the participants valued their conversations. They enjoyed talking with people with whom they had formerly sparred via news interviews.

Gradually, each side’s negative stereotypes were replaced by greater understanding and respect for their opponents. They also discovered that they enjoyed each other’s company. They grew to be friends, celebrated birthdays together, and shared the ups and downs of their lives.

Rehumanizing the fight led to their hoped-for public outcome—the participants toned down their name calling, spoke up loudly for nonviolent means of change, and instructed their organizations to treat the people on the other side with respect.

Truth statements and policy

The Boston leaders didn’t try to agree on policy, but in June 2022, a different, small group of 22 residents in Jessamine Country, Kentucky, interested in abortion rights succeeded in doing just that.

They used a guide for how to structure conversations produced by the nonprofit Braver Angels, an organization I volunteer with, that sets out how to find common ground among those with opposing viewpoints. Their aim: create agreements about abortion between conservatives and liberals.

One key to the group’s success was a selection of background readings by abortion-rights and anti-abortion authors that established a shared set of facts about abortion. For instance, there is a strong link between abortion and poverty, in that three out of four women seeking abortions are poor or low-income.

The Kentucky abortion conversation also focused on a goal everyone could support—reducing unwanted pregnancies and, consequently, abortions. The result was unanimous agreement on two concrete policy recommendations: better, age-appropriate sex education in Kentucky schools, and long-acting reversible contraception that is free of charge for Kentucky residents, modeled after the Colorado contraception program, which reduced abortion rates by 60% and birth rates by 59% among teenagers aged 15–19 from 2009 to 2014.

The participants are now working to communicate their recommendations to state legislators, local pastors, the local health department, and the news media.

Beyond these cases

The empathetic dialogue strategies used in Massachusetts and Kentucky may work in the longer term to reduce polarization in other places, too, and build greater consensus on future policy.

Ireland, for example, voted in 2018 to roll back the country’s restrictive abortion law, replacing it with a new constitutional amendment that permits abortion during the first 12 weeks of pregnancy, and later if a woman’s life or health is at risk or the fetus has an abnormality.

Just as the Kentucky group did with their shared readings before they met, Ireland undertook joint fact-finding before the amendment vote, via a 100-person constitutional convention. When it came time to vote, empathetic story sharing played a key role. Nearly 40% of those who voted to remove the abortion prohibition said their vote had been influenced by hearing from a woman about her experience.

These same lessons could apply to abortion in the U.S.

John Wood Jr., chairman of the Republican Party of Los Angeles County, called for the same respectful type of conversation in a story he told in July 2022 about his long-ago teenage girlfriend’s abortion.

“I cannot hate my fellow Americans who have dedicated their lives to either side of this issue,” he wrote. “There is deep humanity on each side of this divide.”

The groups in Massachusetts and Kentucky show that dialogue works. They built personal connections that crossed their respective ideologies, showed respect for different opinions, and pushed for change that they could all support.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

3 May 2024, 11:47 am - Happiness Break: A Meditation on Pilina: Our Deep Interconnectedness, With Jo Qina’auPilina is an indigenous Hawaiian word, or concept, that describes our deep interconnectedness. Harvard clinical psychology fellow Jo Qina'au guides us through a contemplation of our profound interrelationships.2 May 2024, 10:00 am

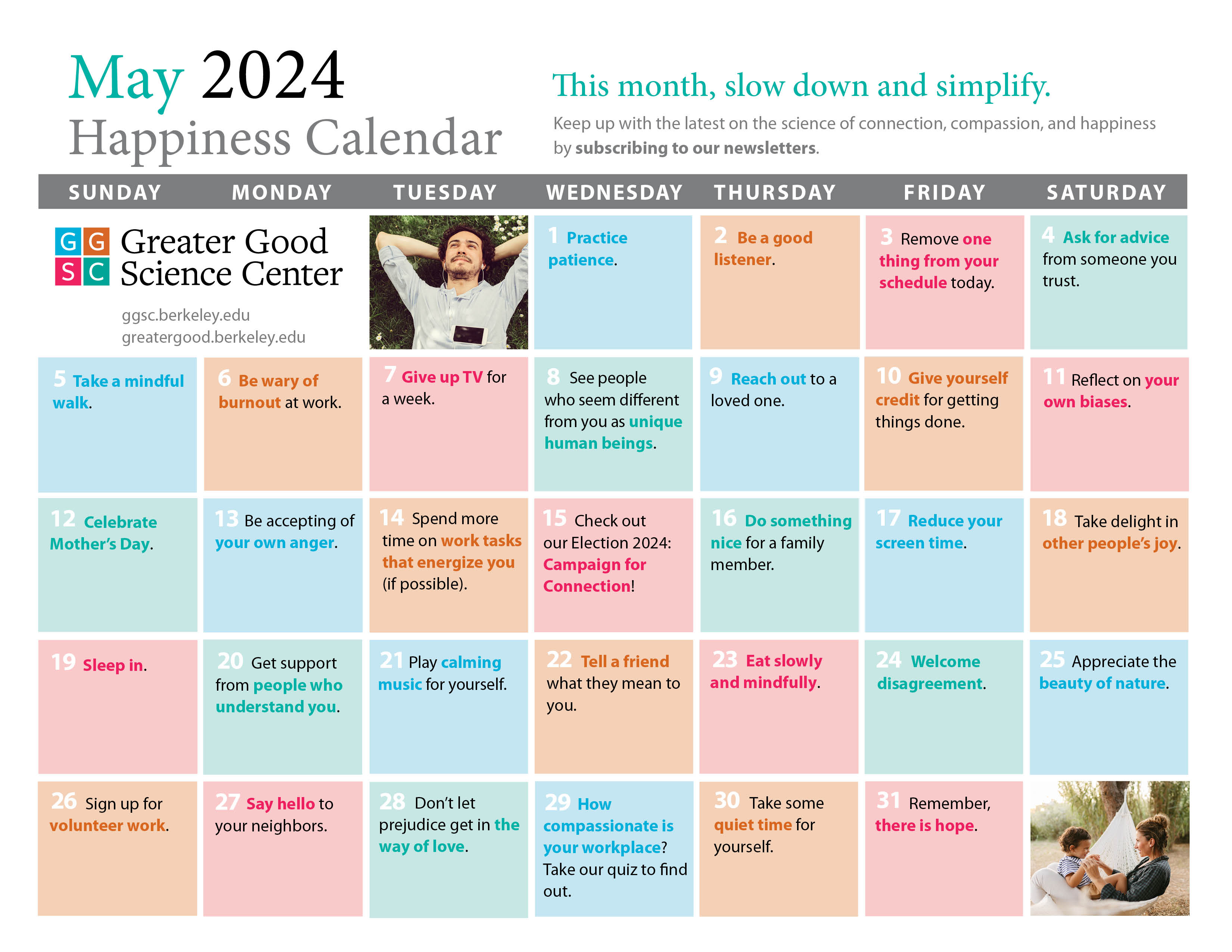

- Your Happiness Calendar for May 2024

Our monthly Happiness Calendar is a day-by-day guide to well-being. This month, we hope it helps you slow down and simplify.

To open the clickable calendar, click on the image below. (Please note: If you are having trouble clicking on calendar links with the Chrome browser, try these tips to fix the issue or try a different browser.)

{embed="happiness_calendar/subscribe"}

View our other calendars!

1 May 2024, 2:50 pm - Happiness Calendar for Educators for May 2024

Our monthly Happiness Calendar for Educators is a day-by-day guide to building kinder, happier schools where everyone belongs. This month, find more moments of play and connection each day in May.

Be sure to join us on May 21st for a free Zoom meeting around the science of play!

To open the clickable calendar, click on the image below. (Please note: If you are having trouble clicking on calendar links with the Chrome browser, try these tips to fix the issue or try a different browser.)

{embed="happiness_calendar/subscribe" calendar="monthly_educators_happiness_calendar"}

1 May 2024, 10:45 am - Five Things Teens Wish You Knew About Them

When Ellen Galinsky was trying to come up with a title for her massive research project and book about adolescence, The Breakthrough Years seemed fitting. After all, adolescence is a true “breakthrough” time when the brain is developing rapidly and is particularly sensitive to environmental influences. It’s when we seek new experiences, build and strengthen connections, and form essential life skills we will use in the future.

Since the founding of the field of adolescent development in 1904, researchers have viewed adolescence as a time of “storm and stress.” But our expectations—negative or positive—affect how teens behave. That’s why Galinsky believes it’s important to reframe our understanding of adolescence from negative to positive—from dread to celebration.

Across more than nine years, Galinsky surveyed more than 1,600 tweens and teens between the ages of 9 and 19 and their parents, asking them what they want to tell adults about people their age. She hopes parents and caring adults will take their messages seriously.

Eden Pontz: You’ve curated a series of five main messages from young people that they feel are key for adults to understand about them. What are they?

Ellen Galinksy: The first message from young people is “Understand our development.” In our nationally representative survey, we asked parents, “If you had one word or phrase to describe the teen brain, what would that be?” Only 14% of the parents used positive words about the teen brain. The most frequently used word by 11% of the parents was “immature,” and another 8% used similar words. Far too many of us are seeing adolescents as deficit adults. We wouldn’t say a toddler is a deficit preschooler. But we see adolescents as “not adults.”

Adolescents need to be explorative and have adventures. You need to be able to react quickly and know if a situation is safe or not. That’s what they need to do to survive. Much of adolescent research has been on negative risks, like taking drugs, drinking, and making what are often called “stupid decisions.” People wonder, “Do adolescents make these decisions because they feel they’re immune from danger?” That’s not true. Research by Ron Dahl from the University of California at Berkeley has found that when young people are doing scary things, they’re more attuned to danger. They’re learning to go out into the world—to move out and be more on their own. He describes it as “learning to be brave,” a characteristic that’s admired around the world.

The second message is “Talk with us, not at us.” Adolescents need to have some agency—to learn how to make decisions for themselves. I don’t mean to turn everything over to them—but to find an appropriate level of autonomy. They’re right in saying, “Don’t just tell us what to do.” As one young person said, “If we’re the problem, then we need to be part of the solution.” The best parenting, the best interventions, and the best teaching involve adolescents in learning to solve problems for themselves, not having problems solved for them.

The third message is “Don’t stereotype us.” Thirty-eight percent of adolescents wrote sentiments like we’re not dumb, we’re smarter than you think, we’re not all addicted to our phones and social media. Don’t put us all in a big group and say we’re the “anxious or depressed generation” or the “entitled generation,” or the “COVID generation.” Let us be the individuals that we are. Research shows if we expect the worst, we sometimes get the worst. When parents’ views of the teen years were negative—59% of parents had negative words to use about teens’ brains—their own children weren’t doing as well. They were more likely to be sad, lonely, angry, or moody.

The fourth message from adolescents is “Understand our needs.” There’s a stream of research in psychology called the “self-determination theory.” This theory suggests we don’t just have physical needs for food, water, and shelter; we also have basic psychological needs. These needs include having important relationships or caring connections, feeling supported and respected, having some autonomy, and finding ways to give back. I found the kids who had those basic needs met by the relationships in their lives before the pandemic did well during the pandemic.

The fifth message is “We want to learn stuff that’s useful.” That speaks to the importance of executive function skills. People who have these skills are more likely to do well academically, in health, wealth, and life satisfaction, than people who don’t. These are skills like understanding others’ perspectives, goal-setting, communicating, collaborating, or taking on challenges. They’re skills that build on core brain processes that help us thrive.

EP: In the second message, you say adolescents don’t want to be “talked at.” What does that look like, and why does it cause conflict?

EG: We’re likely to talk “at” adolescents versus “with” them for several reasons. The first is that we forget what it’s like to be an adolescent. It’s called “the curse of knowledge.” It’s like a doctor talking to you about a medical condition. The doctor assumes you know what they’re talking about, but you haven’t a clue. It’s because it’s hard for us to not know what we already know.

The second reason is they can look like adults so we can see them like adults.

There’s still another reason why adolescents don’t like to be talked “at.” Teens need some autonomy. Autonomy doesn’t mean complete control. It means being choiceful and feeling you are in charge of your life to some degree. We all need that, but adolescents particularly need it because they know their parents will not always be there.

EP: Instead, adolescents want to be talked “with.” What does that look like?

EG: The research on autonomy support is very useful here. I call it a “skill-building approach.” It includes the following: 1) Checking in on ourselves because our feelings can spill over into how we handle challenges. 2) Taking the child’s view and understanding why they might be behaving how they’re behaving. 3) Recognizing that we’re the adults so we need to set limits. Everybody needs expectations and guidance in their lives. Nobody wants to be without guardrails. 4) Helping adolescents problem-solve solutions.

What does problem-solving look like? Here’s an example—“shared solutions.” I’ve used this approach as a teacher and as a parent. If there’s a problem—for example, kids aren’t keeping their curfew, homework isn’t getting done, they’re on their devices, or they’re disruptive in class—you state the problem and what your goals are. Then, you ask the young people to suggest as many solutions as possible. They can be silly ideas, they can be wonderful ideas, you can even get jokey about it.

Then you go through each idea and ask, “What would work for you in that idea? What would work for me?” You are helping adolescents to take your perspective. Next, you come up with a solution to try together. Now you both own that solution. If you need consequences, that’s when you establish them—not in the heat of the moment. Finally, you say, “This is a change experiment. We’re going to see if it works.” You try it out. And if it does work, great. It probably will for a while, but when it needs changing, you go through the shared solutions process again.

EP: What are some things we do that may send unintended messages to adolescents, that leave them feeling unseen or unheard? And what can we do instead?

EG: The late child psychiatrist Dan Stern once said, “Every human being wants to feel known and understood.” It isn’t just our children or younger people. It’s all of us.

I asked some open-ended questions in my study. One of them was, “If you had one wish to improve the lives of people your age, what would it be?” A number of young people wrote about the things that made them feel unseen, unheard, and not understood—statements like “Get over it,” “You’ll grow out of it,” “Stop being such a teen,” or “It’ll get better.” To them, statements like those made them feel that the adults in their lives weren’t understanding, weren’t taking their problems seriously. We’re better off if we try to understand what our kids are trying to achieve with communication before we respond to it.

EP: What are things parents can do to ensure their child knows they are supported and a priority?

EG: Here’s an example from my own life. My daughter was upset at my grandson for loving technology as much as he does. And she told him so in no uncertain terms. He said, quietly under his breath, “But you’re on it all the time, too.” And he was absolutely right.

We had a family meeting where he told his mom how he felt, with her acting one way to him and living another way. And she listened to him and was more mindful of how she used technology. That made a big difference in their relationship. So many young people wrote in, “We see you,” or “You think we don’t understand, but we’re watching you,” or “We’re learning from what you’re doing, not just what you’re saying.” At our best, we need to live the way we want them to live.

Discover more from our conversation with Ellen Galinsky at parentandteen.com.

30 April 2024, 11:44 am - Can Parenting Make You a Better Person?

By nearly all measures, my first son was an easy kid. Whereas most young children are walking, raging ids, Augie was sweet, composed, and strategic. He didn’t have tantrums, and put little effort into asserting power just for power’s sake. Instead, he was prone to careful, deliberate calculations, a pragmatist in Velcro shoes. No battles over wearing the fire-truck T-shirt instead of the police-car one; no tears if the cookie broke in two. He was still getting to eat a cookie, after all.

Raising this kind of child made it easy to do the type of things that usually cause great stress to parents of young children. We could eat meals at quiet restaurants, travel long distances, visit art museums, and count on him to endure a day of tedious errands. At night, I went to sleep less physically exhausted than many of my peers, and grateful for it.

But emotionally and intellectually, I was perplexed. This child of mine, at an unusually early age, had already begun replacing instinct and intuition with reason.

While most parents struggled to get their kids to listen to others, my job was to get Augie to listen to himself. I wanted him to see the world on his own terms, less beholden to external factors. In order for this to happen, I knew I would have to consciously and deliberately get out of his way.

This was not something that came naturally to me. At the time when I had Augie, I was making my living in the “hot take” internet boom of the 2010s; strong opinions were my livelihood. Ask me a question or point to any news story, and by the end of the day I could hand over 800 hard-edged words on the subject—convinced I was right. When I wrote, I didn’t lie so much as ignore the other truths that would have blurred the singular fact I was focusing on. I had to draw a quick and neat line separating right

from wrong, and present the judgment as absolute and obvious.Pre-motherhood, I worried about how parenthood would ruin my ability to work, and in the end it did just that—but not in the way I expected. No, caregiving didn’t make me want to stop working, or worse at it. Instead, I began to question the type of work I was doing as an opinion writer, the kind of person I had become through this work, and whether there could be a better way to exchange ideas.

That process started with Augie and intensified when I had Levi, his far more passionate brother, four years later. The deeper I got into caring for two distinct individuals, the more I began to question the certainty I paraded around in my writing and in my life. There are—an obvious and yet still often surprising truth—so many ways for a person to be.

Up until that point, my formal ethical education consisted of an intro to philosophy course that I had dropped out of after three weeks during my sophomore year in college. Instead of conversations about big questions about how to live well, the class was focused on (much to my disappointment) out-there theoreticals that we would have to solve with logic. Better, I thought, to stick with poets. This worked until I had kids and realized I needed more in the way of philosophical guidance. How I thought I should be, how I thought a person should be, was rapidly being exposed and punctured by care.

Philosophies of care

Few of us consider ourselves philosophers, but all of us think philosophically. We try to figure out what the “right” thing to do is in complicated situations, and contemplate what really matters in life. At an early age, we are taught to separate right from wrong, and that sense of right is supposed to come from within: Do unto others as you would want done unto you.

As we get older, we’re often taught to rely more heavily on reason and think more broadly about right and wrong on a societal level. Maybe, if we are ambitious, we use this reason to try to reckon with universal truths about freedom and justice, or wrestle with highly abstract and complicated philosophical hypotheticals, like philosophy 101 favorite the “trolley problem.”

But these big-picture ideals and hypotheticals, with all their abstract thinking and emotionless gamification, could only tell me so much about how to live my life. The one where people aren’t tied up, like they are in the trolley problem, but rather complicated, vulnerable beings who need something from me. I needed something else from philosophy, something that helped me understand the moral awakening I was experiencing in parenthood. I found this in the work of a lesser-known corner of philosophy called care ethics.

There I discovered the work of women like Nel Noddings, who explores how our instinct to care, an instinct that surfaces as early as infancy, is the foundation of our obligation to be good. This is a long way away from the many psychologists and philosophers who believed that intimate relationships—with all their biases, contradictions, and irrational moments—could be a hindrance to moral thinking. Noddings turns this 180 degrees, arguing instead that care is one of the greatest methods of ethical education.

Through her work, I began to think about what exactly care is, and what it means to do it well. Noddings distinguished between “caring for” someone, which she defines as meaning we both give attention to the recipients of our care and respond to them, and “caring about,” which means we give the recipients of our care attention but don’t necessarily respond. She also separated out what she calls “virtue carers” and “relational carers.” The former are caregivers who do what they think is right for the person being cared for. The latter are caregivers who attempt to understand what the person being cared for needs and then go about trying to provide that for them.

I went into parenting thinking of my children like the readers of my opinion pieces: in need of a clear and firm take on the world around them. But what they needed wasn’t a steadfast guide, but someone who stopped to pay close attention to their needs. On my best days, I am a “relational carer.” I respond to questions with more questions, I remain curious about their desires, all the while hushing the part of me that thinks, “This should be different, better; they could be different, better.” With time, I began to treat others—friends, acquaintances, and even strangers—this way as well.

As Noddings sees it, these moments of engrossed, responsive care can help the caregiver form an “ethical ideal” of the kind of person they want to be, a best self that will serve as a lodestar or reference point in other moments. “I have a picture of those moments in which I was cared for and in which I cared, and I may reach toward this memory and guide my conduct by it if I wish to do so,” she writes.

Philosophers have long contemplated the ways moving beyond our own perspective can be a moral act. Simone Weil, a philosopher who was born in France in 1909, called attention “the rarest and purest form of generosity.” Iris Murdoch, an Irish and British novelist and philosopher, said that “goodness” happens when we “pierce the veil of selfish consciousness and join the world as it really is,” she writes. Martin Buber, an American philosopher and Jewish theologian, encouraged his readers to try and see the other not as an object, but a messy, complicated entity that we experience in all their surprising, confusing, and delightful complexity. “All real living is meeting,” he said.

And yet, if it were ever so simple. Sometimes caring for others makes us better humans overall, and sometimes it doesn’t. For every caregiver or parent transformed by care, there are plenty of parents and caregivers who have been casually awful, or even committed gross atrocities, to those they aren’t caring for while absolutely adoring the people they did care for.

Making care universal

Evolution plays a role here. We are wired to care for those we identify with—whether that’s our family, tribe, or compatriots—more than those we don’t identify with. This can make us biased, shortsighted, and even selfish. It’s why we can at once care about our children while treating the woman we employ to care for them poorly. Or why we can care about the person caring for our children while ignoring the reality of her children living in the same neighborhood, or thousands of miles away.

Still, when a man says being a father changed him, made him more empathic and patient to all, or when a wealthy woman says taking care of her infant made her realize how important universal parental leave is—that now she cares about all mothers—the metamorphosis strikes us as both plausible and sincere.

Care ethicist Sarah Clark Miller has wrestled with how care has the potential to open our hearts to some, while also treating others poorly. Her big philosophical question is: How do we bridge this gap? How do we make it so our intimate experiences of care, including all those insights into human dependency, vulnerability, and subjectivity, extend to the wider world and translate to a more caring society?

We could, she realized, think of care as a duty, or a collectively agreed-upon rule and obligation. When care is a duty, it tells us that we must care because it is fundamental to the good life. Care becomes something you do because it’s the right thing to do, a social norm that you don’t think much about. But, and this is where Noddings’s push for receptivity comes in, we can leave the big rules out of how we care. Instead, we should rely on what we learn through tending to that one-and-only person to inform those decisions.

“Back in the early days, there was great optimism in the care ethics community that we just need to care more and then we will become a more caring society,” care ethicist Daniel Engster told me. “It’s not hopeless, but it requires a lot more cultivation than care theorists have thought.”

Cultivation can look like better government policies supporting caregivers, which, besides giving them some financial and practical relief, tell them that what they do matters. It also requires a culture shift that takes us away from seeing humans as a collective of individuals and instead as a collective of relationships.

In some ways, Engster says this shift is already happening, most notably in our conversation about income equality. For a long time, equality meant that everyone had to follow the same rules; now we are more likely to consider how one person’s well-being compares in relation to another, he explained. The more we see each other as people in relation to one another, the more the lessons we learn through care can plug into how we approach the world at large.

There is, sadly, no single, surefire path to becoming a better person, but if the care ethicists teach us anything, it is that relationships are as valid a path for seeking truth, fairness, and goodness as reason. Since becoming a parent, I regularly think of whose philosophical epiphanies count in our society, and how this authority is determined.

The image of Auguste Rodin’s sculpture “The Thinker” often comes to mind. A strong man, sitting down, chin resting on his knuckles; aquiline nose and tense brow drawing the viewer’s attention to his eyes, which, in return, gaze downward, oblivious to his surroundings. Rodin said he intended the man to appear to be thinking with “every muscle of his arms, back, and legs, with his clenched fist and gripping toes.” I like the statue enough but have come to resent the story its popularity tells us about the gestures, postures, and social conditions of deep thought. What about those of us who have discovered themselves in moments of epiphany while looking into someone else’s eyes, holding their hand, or rubbing their back as they laughed or cried or died?

29 April 2024, 2:24 pm - Is There Anything Useful About Cancel Culture?

“Cancel culture” has a bad reputation. There is growing anxiety over this practice of publicly shaming people online for violating social norms ranging from inappropriate jokes to controversial business practices.

Online shaming can be a wildly disproportionate response that violates the privacy of the shamed while offering them no good way to defend themselves. These consequences lead some critics to claim that online shaming creates a “hate storm” that destroys lives and reputations, leaves targets with “permanent digital baggage,” and threatens the fundamental right to publicly express yourself in a democracy. As a result, some scholars have declared that online shaming is a “moral wrong and social ill.”

But is online public shaming necessarily negative? I’m a political scientist who studies the relationship between digital technologies and democracy. In my research, I show how public shaming can be a valuable tool for democratic accountability. However, it is more likely to provide these positive effects within a clearly defined community whose members have many overlapping connections.

When shaming helps

Public shaming is a “horizontal” form of social sanctioning, in which people hold one another responsible for violating social norms, rather than appealing to higher authorities to do so. This makes it especially useful in democratic societies, as well as in cases where the shamers face power imbalances or lack access to formal authorities that could hold the shamed accountable.

For example, public shaming can be an effective strategy for challenging corporate power and behavior or maintaining journalistic norms in the face of plagiarism. By harnessing social pressure, public shaming can both motivate people to change their behavior and deter future violations by others.

But public shaming generally needs to occur in a specific social context to have these positive effects. First, everyone involved must recognize shared social norms and the shamer’s authority to sanction violations of them. Second, the shamed must care about their reputation. And third, the shaming must be accompanied by the possibility of reintegration, allowing the shamed to atone and be welcomed back into the fold.

This means that public shaming is more likely to deliver accountability in clearly defined communities where members have many overlapping connections, such as schools where all the parents know one another.

In communal spaces where people frequently run into each other, like workplaces, it is more likely that they understand shared social norms and the obligations to follow them. In these environments, it is more likely that people care about what others think of them, and that they know how to apologize when needed so that they can be reintegrated in the community.

Communities that connect

Most online shamings, however, do not take place in this kind of positive social context. On the social platform X, previously known as Twitter, which hosts many high-profile public shamings, users generally lack many shared connections with one another. There is no singular “X community” with universally shared norms, so it is difficult for users to collectively sanction norm violations on the platform.

Moreover, reintegration for targets of shamings on X is nearly impossible, since it is not clear to what community they should apologize, or how they should do so. It should not be surprising, then, that most highly publicized X shamings—like those of PR executive Justine Sacco, who was shamed for a racist tweet in 2013, and Amy Cooper, the “Central Park Karen”—tend to degenerate into campaigns of harassment and stigmatization.

But just because X shamings often turn pathological does not mean all online shamings do. On Threadless, an online community and e-commerce site for artists and designers, users effectively use public shaming to police norms around intellectual property. Wikipedians’ use of public “reverts”—reversals of edits to entries—has helped enforce the encyclopedia’s standards even with anonymous contributors. Likewise, Black Twitter has long used the practice of public shaming as an effective mechanism of accountability.

What sets these cases apart is their community structure. Shamings in these contexts are more productive because they occur within clearly defined groups in which members have more shared connections.

Acknowledging these differences in social context helps clarify why, for example, when a Reddit user was shamed by his subcommunity for posting an inappropriate photo, he accepted the rebuke, apologized and was welcomed back into the community. In contrast, those shamed on X often issue vague apologies before disengaging entirely.

The scale and speed of social media can change the dynamics of public shaming when it occurs online.Crossing online borders

There are still very real consequences of moving public shaming online. Unlike in most offline contexts, online shamings often play out on a massive scale that makes it more difficult for users to understand their connections with one another. Moreover, by creating opportunities to expand and overlap networks, the internet can blur community boundaries in ways that complicate the practice of public shaming and make it more likely to turn pathological.

For example, although the Reddit user was reintegrated into his community, the shaming soon spread to other subreddits, as well as national news outlets, which ultimately led him to delete his Reddit account altogether.

This example suggests that online public shaming is not straightforward. While shaming on X is rarely productive, the practice on other platforms, and in offline spaces characterized by clearly defined communities such as college campuses, can provide important public benefits.

Shaming, like other practices of a healthy democracy, is a tool whose value depends on how it’s used.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

26 April 2024, 11:13 am - Are You Remembering The Good Times? (The Science of Happiness Podcast)Thinking about happy memories activates reward centers in our brains, and can help us feel more connected and accepted. Palestinian-American poet Naomi Shihab Nye discovers the joy-bringing power of recalling her good childhood memories.25 April 2024, 10:00 am

- Are Merit-Based Systems Actually Fair?

Fairness is an important value among many of us. That’s why we want to make sure sports competitions are free of unfair advantages (like steroid use), students can’t plagiarize when writing papers, and businesses are honest in their dealings. We want people to deserve their successes.

Yet when it comes to hiring or admitting a student to college, we often base our decisions solely on people’s observed performance or talents—in other words, their “merit”—rather than how they were able to achieve them. We might overlook the fact that one candidate had an unfair advantage over another for some reason.

Should that matter? A new study suggests it should—and finds that both conservatives and liberals endorse this view.

Is meritocracy fair?

In the study, researcher Daniela Goya-Tocchetto of the University of Buffalo and her colleagues surveyed thousands of Americans who identified as either liberal, independent, or conservative politically, to see how learning about disadvantages might affect their view of merit-based decision making.

First, participants were introduced to two people vying for a job or promotion—Jim and Tom—and told how a merit-based decision would be made. For example, they might read that the hiring committee was focused only on getting the most qualified candidate for the job and that Jim is the clear choice, because he has better grades and a lot of extracurricular activities and internships.

Some participants received no other information about Jim or Tom, while others read information about their backgrounds—such as the fact that Jim grew up in a family with lots of money who could afford sending him to the best schools, while Tom grew up in a family who didn’t have enough money for that.

Afterward, everyone was asked how fair the merit-based selection process was and how fair the outcome was. The researchers also checked to see if people’s political orientation affected their answers.

In all cases, when given background information, people rated the selection process and outcome as less fair. Although conservatives tended to see merit-based systems as fairer than liberals, in general, they were still likely to change their position when hearing that Jim had advantages Tom didn’t have.

This was somewhat surprising to Goya-Tocchetto.

“In the United States, where there is a strong culture of meritocracy, people have a strong belief that meritocratic processes are fair; so this result surprised me,” she said. “But I found it particularly surprising that the information affected people across the political spectrum.”

Most employers wouldn’t necessarily get this kind of background information for everyday hiring and promotion decisions, though. So, Goya-Tocchetto and her colleagues wanted to see if more general information about the effects of economic disparities on opportunity would change people’s views.

In another set of surveys, people either read general information about how income affects our opportunities in life (instead of information about Jim and Tom) or didn’t. For example, they read that people with more money have certain advantages, such as having more time to study and participate in unpaid extracurricular activities in college that could help them get a job when they graduate.

In this part of the study, the researchers also checked whether this information affected people’s support for practices that might even the playing field—such as “using hiring processes that remove prestigious brand-name universities from resumes” or “making internships less of a requirement for getting hired.”

After hearing about merit-based hiring and who received the position, people who’d read about the effects of income disparity on opportunity felt merit-based processes were less fair. And they were more supportive of equity initiatives, too—whether they were conservative or liberal.

This was even more surprising to Goya-Tocchetto—and encouraging.

“To tell a general story about how previous advantages and disadvantages shape markers of merit and have that update people’s perceptions means people are understanding that what they previously assumed were markers of merit aren’t necessarily that,” she says.

Building fairer systems

Does this mean that people might support other measures aimed at being fairer—like affirmative action programs? Goya-Tocchetto isn’t so sure. Her study focused only on economic disadvantages, not other potential barriers to opportunity like those based on race, gender, or ethnicity.

“When it comes to acknowledging racial or gender disadvantages, political conservatives tend to be less likely to acknowledge those. But they are more attuned to disadvantages within the economic domain, and I think our evidence supports that,” she says.

On the other hand, Goya-Tocchetto argues, letting go of meritocracy beliefs can be a hard sell, because selecting people on merit is both easy and intuitive. Organizations need good workers—people with certain skills and abilities—so considering someone’s experience with those seems like a reasonable approach. Using strategies to look more closely at an individual’s background would take more time and effort, something most organizations may not want to do.

Also, merit-based systems themselves were created to improve on prior systems of advancement, like nepotism. So, people tend to think that looking at an individual’s accomplishments or merit, without regard to their background, is relatively fair. This makes it harder for them to consider giving up meritocracy beliefs in favor of something more nuanced.

“Meritocracy can be an appealing ideology,” says Goya-Tocchetto. “Once something becomes the status quo and gives us a simple answer—and we don’t have something simple to replace it—we just get stuck on that.”

Still, she hopes that her research sheds light on something that might surprise people: public support for more fairness in these processes (despite presumed political differences). And, she says, it may point to some specific tips for overcoming the problems with current merit-based systems.

For example, she says, candidates applying for jobs or college admission may want to be more forthcoming about the reasons why they couldn’t pad their resumes with unpaid internships or attend elite schools. And those in a position to make selection decisions may want to be careful about favoring candidates from elite schools with prestigious internships on their resumes. They may want to consider how hard someone had to work or how much they had to overcome in order to get where they’re at.

Perhaps if we can better appreciate how people value fairness and what it takes to make our hiring decisions fairer, we can come together and create a more equitable way of doing things.

“Meritocracy can make a lot of sense when we look at a snapshot of reality, but as soon as you expand the lens through which you’re looking at the world, the merit process becomes so biased,” she says. “Once we talk about and acknowledge that, maybe we can shape people’s views about what ‘equal opportunity’ really means.”

24 April 2024, 12:09 pm - Can Awe Help Students Cope With Climate Change?

Every so often, we have the rare fortune to experience transformational moments that change how we see ourselves and the world around us. This was the case for me in early 2023.

The Caribbean is beautiful and one of the most captivating regions of the world. Yet it is disproportionately vulnerable to natural disasters like hurricanes and earthquakes that have been exasperated by the impacts of climate change. As a National Geographic–certified educator and explorer specializing in oceanography and climate science, my fieldwork takes me across the Caribbean to help restore marine habitats and coastal resilience. Research finds that the mental health of children in the Caribbean is also disproportionately vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

When time allows, I make it a point to visit local schools to help students understand the importance of protecting our ocean and the science behind climate change. Over the course of that year, I had gotten to know one group of ninth-grade students on the island of Jamaica quite well. One morning during our class, an intense hurricane was brewing in the Atlantic Ocean, and, for the first time, I witnessed childhood trauma. Their webcams were mostly turned off, which was unusual; those who kept them on were visibly despondent.

With some quick thinking, I decided to forgo my lecture on rising sea levels, which included images of floods and decimated coastlines. Instead, I showed students underwater footage of the coral restoration work my team and I recently completed off the north coast of Jamaica. I also shared short video clips of the lush landscapes surrounding the island’s beloved Blue Mountain range. After the videos, I shared a few affirmations and explained how I use daily affirmations to help conquer my fear of swimming in the ocean’s deep blue waters and hiking up steep mountain trails.

What happened next was miraculous. I saw students’ eyes begin to lighten as their cameras turned on. Their faces softened as they sat transfixed, watching the video. They cheered with amazement as they watched a local cliff diver perform a backward triple somersault before plunging into a hidden waterfall. After the video, we discussed our human connection to the ocean and natural landscapes.

Later that evening, I reflected on how the iridescent blue ocean scenes and rich landscapes seemed to awaken their senses and create in them a sense of calm and ease. Astonished by what I had witnessed, I combed the internet for words to help describe my student’s transformational experience. That’s how I stumbled upon the concept of awe!

The presence of something vast

“The epiphany of awe is that its experience connects our individual selves with the vast forces of life,” writes psychologist and GGSC cofounder Dacher Keltner in his latest book, Awe: The New Science of Everyday Wonder and How It Can Transform Your Life. “In awe we understand we are part of many things that are much larger than the self.”

He defines awe as the “feeling or an emotion of being in the presence of something vast and mysterious that transcends your current understanding of the world.” Keltner further explains that the vastness we perceive challenges our existing knowledge and compels us to seek a greater understanding of phenomena. Awe draws our attention away from the self and turns our attention to other phenomena and to that which is larger than life. If that isn’t enough, research finds that awe improves our well-being and mental health in the face of uncertainties. Awe helps us to find meaning and a purpose in life.With just a few short video clips and the opportunity to share what I find so fascinating about the ocean and other natural landscapes, I was astonished to see how inspired my students were to learn more about conservation. Their faces were aglow as they asked a barrage of questions and shared their thoughts with each other. One student expressed how he felt uplifted and strong when he saw the towering Blue Mountains. Another shared that she had been feeling depressed lately, and the video “made me feel like I can make a difference in my community by learning to do restoration work, too!”

Motivated by my students’ experience, I spent most of 2023 immersed in Dacher Keltner’s research on the science of awe, and I also took the Greater Good Science Center’s course Awe in Education: Creating Learning Environments That Inspire, Motivate, and Heal.

With generous funding from the National Geographic Society, my team and I curated more engaging activities integrating multimedia content from my exploration fieldwork. These activities were designed to inspire awe and healing spaces to help counter the stress, anxieties, and trauma that vulnerable students often face due to climate impacts. These trauma-informed and culturally responsive activities shift the focus away from natural disasters and catastrophes, which are often overemphasized in climate education, and help students understand their connection to the vast and wondrous world around them.

Through careful observation and student feedback, I found that when placed in a safe, nurturing environment and engaged in meaningful, expressive, and guided activities, most of the children who participated in the exercises stated that they were able to experience awe. Here are two favorites.

1. Awe-inspiring affirmation practice

The “Awe-Inspiring Affirmation” practice helps foster resilience by cultivating inner voices of happiness. To help foster deep connections to nature and universal belonging, students view images and videos of vast and awe-inspiring landscapes and listen to motivational speeches, music, poetry, and performing arts that exude transformation.

After this, students create their own inspiring affirmations (written or spoken positive phrases) to raise their awe vibrations and affirm their self-worth. When we frequently engage in positive self-talk, we open up a new way of believing in ourselves and what we can accomplish. In this practice, awe-inspiring natural landscapes inspire students to write personal affirmations that bring out the best of human capability and goodness.

To build deeper connections with my students, I share with them how I use affirmations to help me stay focused on positive outcomes and accomplishing personal goals. I then give students a list of affirmations that other students created from previous classes. After reviewing the list, I ask them first to watch an awe-inspiring video and then take a brief moment to reflect on how affirmations might be helpful in their lives. Working alone or with partners, students craft their own affirmations and share them with the class to encourage each other.

Incorporating activities that inspire awe and affirmations in the classroom is an excellent way to foster deeper connections with your students and promote a positive classroom culture. Affirmations have been found to help students succeed and set a positive tone for the day. Like adults, young people also need time to reflect on what is meaningful and experience moments that inspire awe. By giving students opportunities to ground themselves in positive affirmations, we can help them find purpose and achieve their goals. Most importantly, creating space for reflection can help students slow down and find comfort during times of uncertainty.

2. Seeking connection to vastness

Research finds that reflecting on vastness can help negate students’ stress and help them gain a new perspective on life. In this practice, students watch a video about the vastness of the universe and are invited to share how it made them feel about their existence and interconnection with all living things. This practice can also be modified by integrating an awe-inspiring video and relevant questions for a specific lesson or curriculum activity.

For my students, I replaced the suggested video with drone footage I captured while exploring the vast landscapes of Dominica, the Caribbean’s “Nature Island.” Students were captivated by its beauty. Many had never traveled to other Caribbean islands and were awestruck to see Dominica’s resilience in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria in 2017. The practice helped my students be aware that they are connected to something larger than the worries and stress they often feel.

In the face of a global mental health crisis and unprecedented climate change impacts around the world, we must be willing to constantly adapt and refine our educational practices to meet the evolving emotional needs of our students. By doing so, we can offer students moments to pause, build emotional resilience, and be inspired by the awe and beauty of the world around them. I hope all children will know they are an intricate part of a vast universe of possibilities.

23 April 2024, 12:57 pm - When Is Divorce Good for Women?

Divorce is having a moment—for women.

For example: Actor Drew Barrymore, who recently divorced for the third time, shared on her talk show that divorce is liberating.

I had so much shame around divorce and, for some reason, something happened, and I said, “I’m no longer willing to feel this way.” And it just lifted from me. When you find yourself in a situation that isn’t working out the way you hope and want, you accept it and improve the quality of life by moving forward. And for me, divorce is no longer a reason for shame. I am totally free.

For her part, model Gisele Bündchen says it takes “courage to leave an unhealthy relationship” and sees her divorce from football star Tom Brady as a new opportunity for her—“when a door shuts, other doors open.” Model Emily Ratajkowski marked her recent divorce from Sebastian Bear-McClard by turning her engagement ring into a divorce ring and praising how transformational a divorce can be, especially for women.

Women, who are overwhelmingly the ones to initiate divorces, actually are feeling better about it. In fact, they are celebrating it. A few years ago, those celebrations looked like divorce parties, divorce cakes, divorce registries, and divorce selfies.

More recently, Gen X women have turned to writing memoirs that put their marriages, as well as the institution of marriage, under the microscope and magnify just how toxic heterosexual marriage can be. These memoirs, from Australian author Clementine Ford (I Don’t), and American authors Leslie Jamison (Splinters) and Lyz Lenz (This American Ex-Wife: How I Ended My Marriage and Started My Life), not only skewer heterosexual marriage but also praise breaking free.

As someone who has been divorced twice—once after a short-lived marriage when I was in my early 20s, and once at midlife with two tween children—and who has written extensively about marriage and divorce, I know a thing or two about both.

I don’t regret either of my divorces. As weird as it may sound, divorce was the best thing that happened to me (besides having my children). In fact, I would never have become an author if I had not left my last marriage, which lasted 14 years.

Divorce is much more commonplace and accepted nowadays—a recent Pew Research Center survey reveals that 55% of Americans believe unhappy spouses tend to stay in bad marriages longer than they should. But should we be celebrating divorce, especially if young children are involved?

The answer can be yes. There is a positive, research-based case for divorce—if the split happens under the right conditions.

What can be good about divorce?

Paul R. Amato is a sociologist at Penn State University whose research focuses on marital quality, divorce, and family issues. In his 2000 review of research on the consequences of divorce for adults and children, he notes that numerous studies have found that many people flourished after divorce. They experienced higher levels of autonomy and personal growth once untethered from their marriage. Many women had a boost in self-confidence and a better sense of control. Divorced moms tended to see improvements in their career opportunities and their social life, as well as an increase in happiness.

While most studies of the past tended to focus on the negative consequences of divorce, he writes, “If more studies explicitly searched for positive outcomes, then the number of studies documenting beneficial effects of divorce would almost certainly be larger.”

Some more recent studies have done that.

“There is a societal assumption that divorce is always negative,” says Connie R. Wanberg, a professor at the University of Minnesota who recently co-authored a study on how divorce impacts people in the workplace. Still, even Wanberg was surprised how many said they were better at their jobs after their split. “Some of these individuals had been in very dysfunctional relationships,” she says.

Like the recent divorce memoirs reveal, women tend to thrive post-divorce, not necessarily financially (in fact, many women suffer unnecessary financial hardship in a divorce), but emotionally and physically.

Women are “significantly more content than usual for up to five years following the end of their marriages, even more so than their own average or baseline level of happiness throughout their lives,” according to a 2013 study from London’s Kingston University.

One reason women feel happier than men after a divorce, despite the financial repercussions, could be that “women who enter into an unhappy marriage feel much more liberated after divorce than their male counterparts,” according to Yannis Georgellis, director of the university’s Centre for Research in Employment, Skills and Society, who co-led the study.

Women are more likely than men to get mental health support while divorcing, more likely to depend on supportive relationships, less likely to rely on drugs or alcohol post-divorce, and more likely to turn to experiences that enrich them, such as travel, researchers observe.

San Francisco Bay Area therapist and author Susan Pease Gadoua has been offering groups for women in transition since 2000, mostly to divorcees and soon-to-be divorcees. For many years, a consistent theme she heard was how ashamed they felt as well as experiencing a sense of failure.

If “until death do us part” is how society measures a successful marriage, a union that ends in divorce, instead of death, is seen as a “failed marriage,” even if the marriage was loveless, sexless, lonely, and full of anger and perhaps contempt.

While some gray divorcees—boomers in their 60s and older, a cohort that is divorcing faster than any other age group—Gadoua counsels still feel those pressures, most of her younger clients do not.

“There’s definitely less stigma and it’s not uncommon to hear from women who come to see me that they’re on their second divorce, even third. That’s quite prevalent. Those numbers don’t seem to matter anymore,” she tells me.

Boomers grew up in an era when there was little to no help for parents going through a divorce, or their children. And the influential books penned by therapist Judith Wallerstein—1989’s Second Chances and 2000’s The Unexpected Legacy of Divorce—convinced millions that divorce was more harmful than previously thought and with lifelong consequences for young children caught in the crossfire. Her methodology and research, however, have since come under scrutiny and been criticized.

“The idea that divorce is bad, and kids are going to be damaged, those are really outdated beliefs. We have the choice to have a different kind of divorce today, for people to think, ‘Oh, I have the power to make this a good divorce,’” Gadoua says. “It can bring out the worst in people, but it doesn’t have to.”

Coming back to life

Still, mothers who leave their marriages while their children are still young, as Barrymore, Bündchen, Ratajkowski, and all the memoirists did, are often judged harshly.

“Mothers in almost every culture are programmed to bury their needs in the greater needs of family. Acting on their own desires, following their hearts, searching out their own private happiness—all of this is still perceived as transgressive and profoundly selfish,” British author Lily Dunn writes of her decision to leave her husband for another man while her two children were young.

As famed therapist Esther Perel writes in her book The State of Affairs: Rethinking Infidelity, “Home, marriage, and motherhood have forever been the pursuit of many women, but also the place where women cease to feel like women.”

Which is why divorce often kickstarts a woman’s libido.

“For women who appear to have ‘low desire’ in long-term marriages, many times when they get divorced they’re sleeping around with everyone,” sexologist Tammy Nelson and author of The New Monogamy: Redefining Your Relationship After Infidelity, tells me. “People confuse the loss of sexual interest with the loss of sexual interest with a specific person.”

And for some heterosexual women, a divorce leads them into the arms of another woman for the first time, as described by authors Elizabeth Gilbert and Glennon Doyle in their bestselling memoirs. In fact, some 36% of women in their 40s in a same-sex relationship had been previously married to men. It’s higher for women in their 50s and older.

“[M]any women report feeling a ‘second adolescence,’ with many of the associated feelings and behaviors. She is not crazy if she suddenly has sex on the brain all the time!” writes Nancy C. Larson in her 2006 study “Becoming ‘One of the Girls’: The Transition to Lesbian in Midlife.” Larson herself came out as lesbian after 19 years of marriage to a man.

No one would promote divorce as a path to sexual pleasure. Still, a 2018 study of middle-aged hetero, bisexual, and trans divorcees found that while some of the women had regrets about the end of their marriages, divorce got them out of their comfort zone and opened them up sexually.

“Women sometimes have to break rules to find sexual pleasure for themselves in a society which is not consistently supportive of female sexual pleasure,” the researchers wrote. “It also takes seriously women’s right to seek pleasure and to overcome barriers to pleasure even if those barriers are socially sanctioned.”

Mothers and children

Of course, divorced moms aren’t just focused on their sexuality. They focus on their children, too.

According to a 2019 U.S. Census Bureau report that culls numerous studies in the States and overseas, divorce laws can hugely benefit divorced moms, who often invest more in their children’s schooling. They also have more time to spend on leisure as well as work, and spend less time on chores.

That’s what Lyz Lenz discovered, in part because she had 50-50 shared custody with her former husband, as an increasing number of divorced parents in the United States do, according to a 2022 paper, “Increases in shared custody after divorce in the United States.” As Lenz writes in an essay for Glamour magazine:

I had more time to write and more time to work. I started making more money. I was able to do things I’d never been able to do before: a set at open-mic night at a local comedy club; drive to Minneapolis to see my friends. I had less housework, and I didn’t have to worry about having a fight if I made vegetarian food for dinner, or just didn’t cook dinner at all, or if I swore, or if I wanted to stay out late at a book reading (yes, all real fights we had). I had more friends because I could be a better friend.

In a 2020 study, “Families in Later Life: A Decade in Review,” sociologist Deborah Carr found that although divorce has long been described as among the most stressful of life transitions, more recent studies indicate that many older adults adapt and even thrive post-divorce, from finding new romantic partnerships, to spending more time volunteering, to strengthening ties with their adult children.

Typically, it’s the mothers who have more contact with their adult children after divorce. For dads, later-in-life divorce cuts the odds of frequent contact by nearly half, at least for a while, especially with their sons, mostly because adult children often blame their fathers for the divorce. And while a father’s re-partnering often contributes to those fractures—they’re seen as “swapping families”—a mother’s re-partnering “has no appreciable effects on their relationships with their adult children,” according to a 2022 study.

As Carr shares with AARP, despite some emotional bumps right after a split, most older adults eventually “fare quite well” after a few months. “Whether you’re depressed or not depends upon what the relationship was like and the context in which it ended. If it was a conflictual marriage and not emotionally satisfying, there are fewer symptoms of depression and loneliness.”

Lenz believes divorce is a cause for celebration. She celebrated hers by burning her wedding dress—“a reminder of all my failed dreams”—that had been hanging in her closet for the 12 years of her marriage.

“In response to news of divorce, people often reply, ‘I’m sorry.’ But I think we should say ‘congratulations.’ Congratulations for prioritizing yourself. For being brave. For the self-knowledge to know when to leave,” she writes in the Washington Post.

Gadoua thinks rather than celebrate divorce—although individuals are certainly free to do so—what’s really needed is a way for former spouses to honor the exit from their marriage.

“It’s a personal choice to celebrate,” she says. “I do think that we lack in our culture a rite of passage out of marriage. The women who come to my retreat are so grateful to have a sense of closure and some kind of ceremony around honoring what they had but looking forward to what is in front of them.”

22 April 2024, 3:27 pm - More Episodes? Get the App

Your feedback is valuable to us. Should you encounter any bugs, glitches, lack of functionality or other problems, please email us on [email protected] or join Moon.FM Telegram Group where you can talk directly to the dev team who are happy to answer any queries.

Instructional Coaching Corner

Instructional Coaching Corner

The Flourishing Center Podcast- Life Hacks, Science and How People Put Positive Psychology into Practice

The Flourishing Center Podcast- Life Hacks, Science and How People Put Positive Psychology into Practice

The Greater Good Podcast

The Greater Good Podcast

The Science of Parenting

The Science of Parenting

The Mindful Parent Podcast

The Mindful Parent Podcast